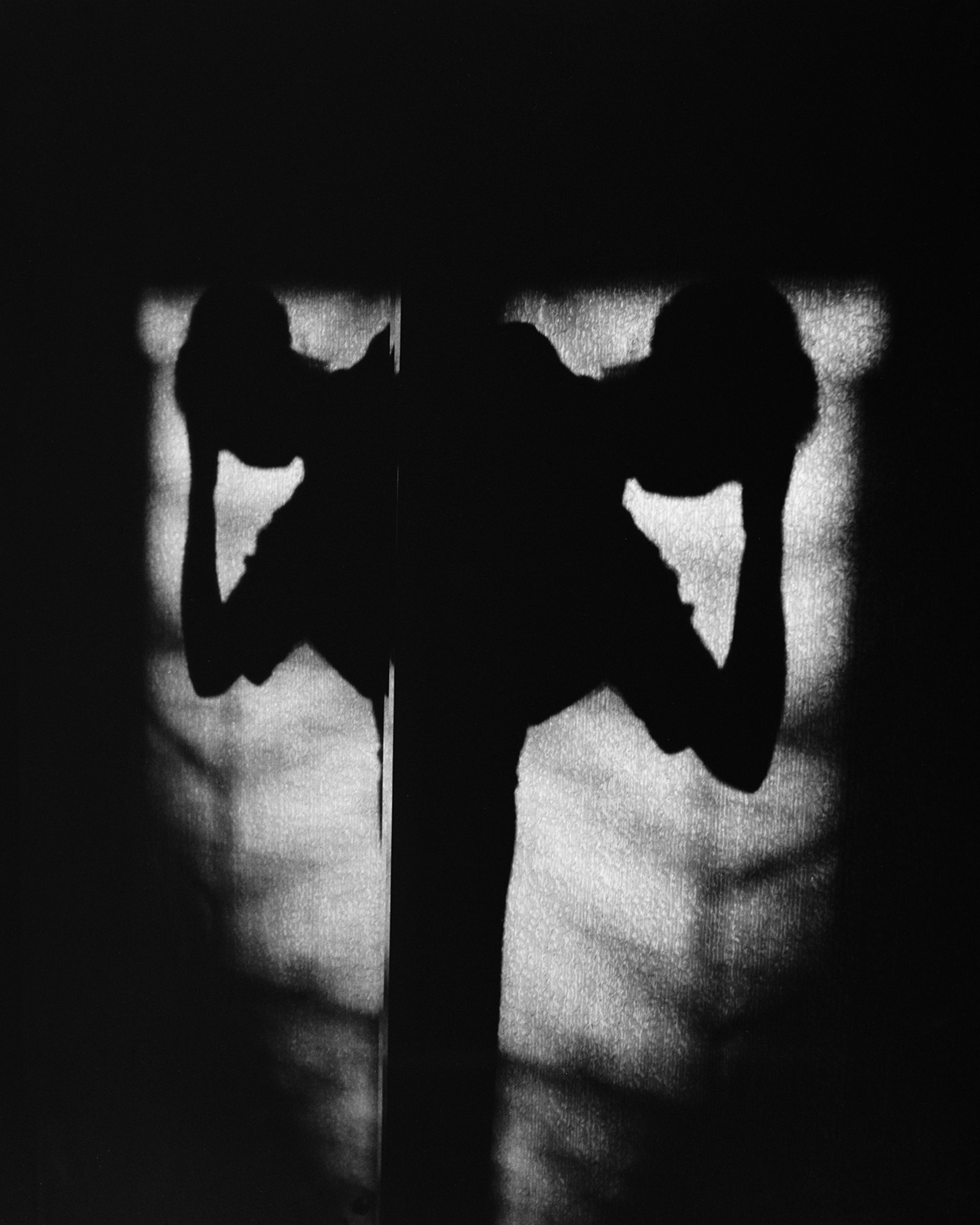

Emila Medková Untitled, from the series Stínohry (Shadowplays), 1949

Dream logic is essentially sideways logic: similarities or kinships that work not by means of sense but along other avenues of relationship. Puns, for example, exhibit dream logic. What kind of socks do bears wear? None. They usually have bare feet.

Visual puns likewise find resemblances between objects not otherwise the same. Since human eyes are self-interested, the similarities they tend to discover are to human faces, from the composite vegetative figures of the sixteenth-century painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo to those comic staples of today’s social media, the carrot that seems to smirk or the leering face in a tree.

Back up eighty years, and here’s the Czech Surrealist photographer Emila Medková, carrying out an austere version of the same absurdist project. Her work spans four decades, from the end of World War II to her death in 1985. With the exception of the brief liberalization in 1968 around the Prague Spring, Medková operated in the dark of totalitarian rule. Her work was rarely exhibited. Censorship was rife and resistance necessarily coded and covert. Her photographs were made as an act of subversion and bitter humor for a close circle of Czech Surrealists.

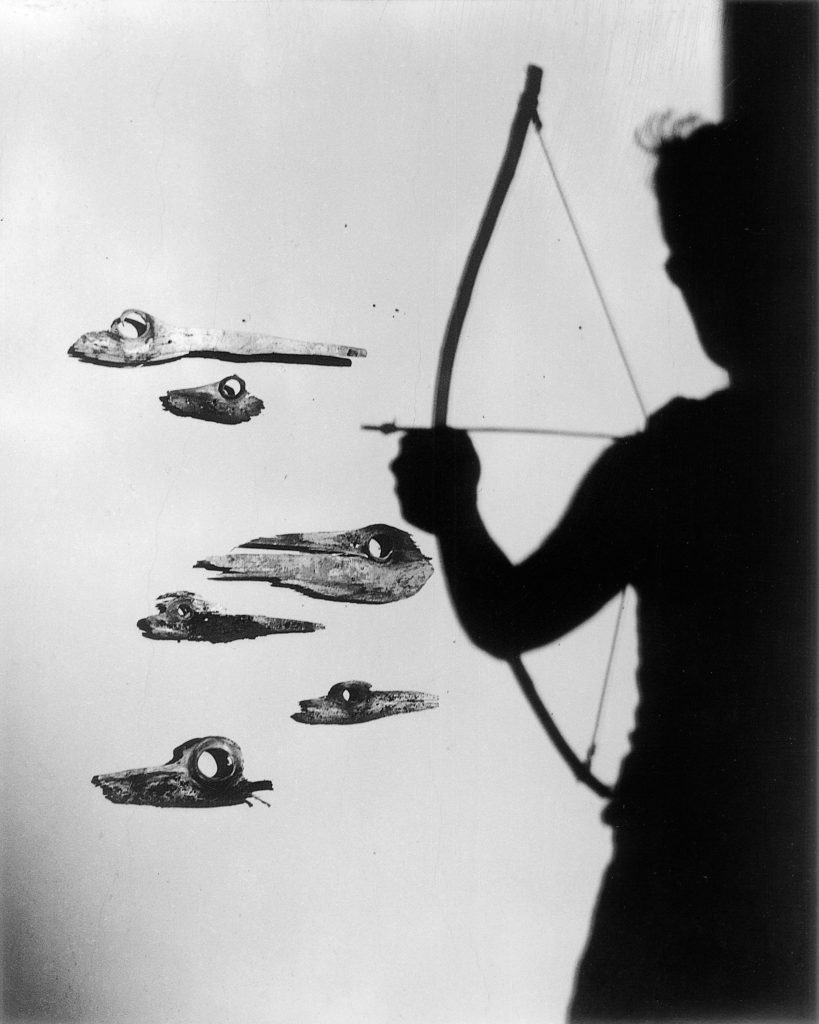

She started out in a fairly conventional, if virtuosic Surrealist mode. In the Shadowplay series of the 1940s, real objects are twinned with their shadow selves, the exception being a female figure in Lukostřelec (Archer) (1949), who exists solely in the domain of shadow. With an arrow, she pursues what looks like a flotilla of fish, made perhaps from knots in wood. In another scene, she gazes at a mysterious assemblage, which includes a tap gushing hair and an eggcup that appears to be capped with an eyeball, cheery as the cherry on an ice cream sundae.

These images have a definite power, but are in some ways reliant on a readymade Surrealist language, which centers on the objectification and estrangement of the female body. In her later work, Medková excised the human form altogether, finding far stranger and more potent bodily resonances by way of objects.

I’ve got four of her found forms in front of me. The first, Zavřená hlava (Closed head), from her long-running series Closed (1960–61), shows the middle region of two wooden doors, their surfaces riven and pockmarked. Each has a square black aperture near the top. Underneath, there’s a metal hasp, yoking the two doors together, which has been padlocked shut. It’s irresistible to read this image as a cartoon face, with doleful eyes and flat mouth. In fact, it looks exactly like the emoji for shhh or zip it, the ideal affective icon for the Stalinist government under which Medková worked.

The face is above all a conveyer of expression, while the object is intrinsically speechless and inert. That’s the weird bathos, the lol of the face-in-object. In Medková’s faces, this tension is heightened by the way they’re so often further encumbered by having their mouths locked, filled, choked, or otherwise impeded. Everywhere, these faces that can’t speak are having their capacity for speech emphatically denied.

In Křik (The scream, 1971), we’re seeing another virtuosic surface, every crater and crevice crisply rendered. Is it a road in close-up? Much of the photograph appears dark, surrounding a pale region shaped like a cartoon face in profile—like the “Kilroy was here” face ubiquitous in 1940s graffiti. Kilroy’s hair is grass and his mouth is enormously wide. It looks as if he’s vomiting the darker matter, or, on the other hand, as if it’s being forced down his open gullet, choking the apparatus from which language is produced.

There’s more uncanniness afoot in an untitled 1951 photograph from the series Inkvizitoři (Inquisitors). The face is made of bark, with a hank of hair, and another single eyeball, maybe a marble, though it looks a lot like what my godson calls “googly eyes” (a natural-born Surrealist, he often sticks them on unsuspecting fruit and eggs). But this face is lying on a table, as food tends to do. It has a fork shoved in its mouth, which pushes it toward the status of face, and a knife skewered through its cheek, which converts it back into food. Object or subject? Who’s doing the eating, and who is being consumed?

One more, this time not a face at all. This image, wittily titled Arcimboldo (1978), shows a crumple of machinery, with intestinal spokes and ribs and teeth. It looks like a torso, the damaged interior of a body. The French Surrealists, well-fed, enjoyed imagining women’s bodies emerging from inanimate objects in ways that were alternately nightmarish and exposing. Medková’s take is more skeptical and scathing.

All photographs © Eva Kosáková Medková

Perhaps this is all a person is, she seems to say, a bundle of disarticulated parts, functional until it’s not. But what could seem like a dutiful totalitarian statement is undermined by the cool, displacing irony of Medková’s gaze. The oddness of the composition makes it impossible not to sense the presence behind the camera. The shadow is no longer necessary. What she’s actually managed to document is a person in the forbidden act of looking, thinking, dreaming freely. Maybe this particular rebellious object wasn’t so silent after all.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 247, “Sleepwalking,” under the title “Sideways Logic.”