A Prolific Video Artist’s Infinite Screens

Raised in Africa and Europe, Theo Eshetu makes kaleidoscopic films that reflect the dilemmas of biography and belonging.

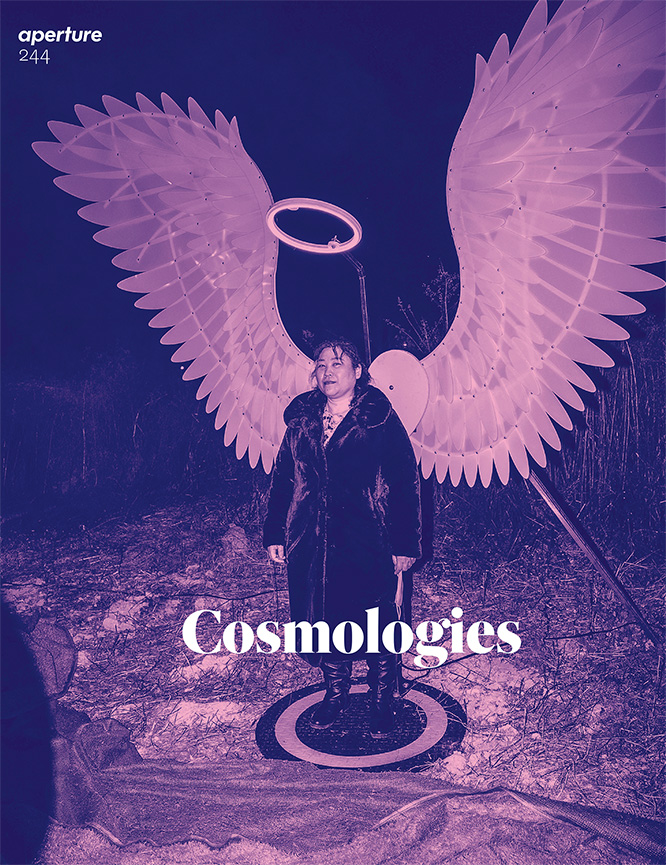

Theo Eshetu, Brave New World, 1999. Multimedia installation

Installation view in Lavori in Corso, 1999, Museo d’Arte, Contemporanea di Roma, Rome

The opening to the mirror box is a gilded frame through which viewers can watch a kaleidoscopic film. Titled Brave New World (1999)—versions of which have been installed in exhibitions in Washington, D.C., Rome, and New York—the film is “a very simple idea but very effective,” as one viewer says to Theo Eshetu, its creator. You poke your head into the mirror box where the film is playing, and where, given the continuous loop of bisymmetrical clips, you get the illusion of being surrounded by seemingly endless reflections of yourself as you watch. Filmed with a Super 8 camera, the footage is looped together from a thrilling array of sources, including a ceremony of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, a commercial for an Italian insurance company, and enchanting images of dancers in Bali. “The idea is that it sort of creates an image of the world, no?” Eshetu asks a mesmerized viewer as they both stand in front of the mirror box, observing its fantastical twists. He is proposing an image of the world tripled or quadrupled many times over, so that what is seen is not simply illusory but infinite and indeterminate, as though gathering the entirety of the world’s faces into a single orb.

Brave New World is a quintessential primer for Eshetu’s four-decade career; the artist’s video work—for cinema, television, and exhibitions—is often an assemblage of images or clips from a range of histories and worldviews. His biography gives a clue as to what informed his nonprovincial outlook. Born in London in 1958 to an Ethiopian father and a Dutch mother, Eshetu spent his childhood between Ethiopia, Senegal, Yugoslavia, the Netherlands, and Italy, due, for the most part, to the peripatetic nature of his parents’ work. When he was ten, he spent time with Ato Tekle-Tsadik Mekouria, his grandfather, a diplomat and perhaps Ethiopia’s most renowned historian. Eshetu was out of school and somewhat bored. During a trip to Pompeii, his grandfather gave him an Instamatic camera, effectively launching his fascination with photography and his career—a recurring origin tale for many artists. “I recognize it’s a cliché story,” says Eshetu.

More than twenty years later, perhaps to make something of that cliché, he returned to Ethiopia to create Blood Is Not Fresh Water, a 1997 film dedicated to the life of his grandfather, whom he had seen only twice in the years since. The film explores the cultural and spiritual history of Ethiopia, drawing a cyclic line from the Queen of Sheba to the pomp of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church to Lucy, the oldest known human skeleton at its discovery. By making Blood Is Not Fresh Water, Eshetu recently told me, he could delve into the contrast between “the TV image of famine in Ethiopia” and his “childhood memory of a bright, wonderful place.” And he could connect with his Ethiopian self. The experience of being biracial causes a split, in a sense, of identity. “I create dialogues between these two perspectives,” he says, connecting his European and African selves. In a statement about the video, he explained, “I don’t have a photographic memory of the places where I lived as a child, but often photographs remind me of a past existence I don’t recall having seen.”

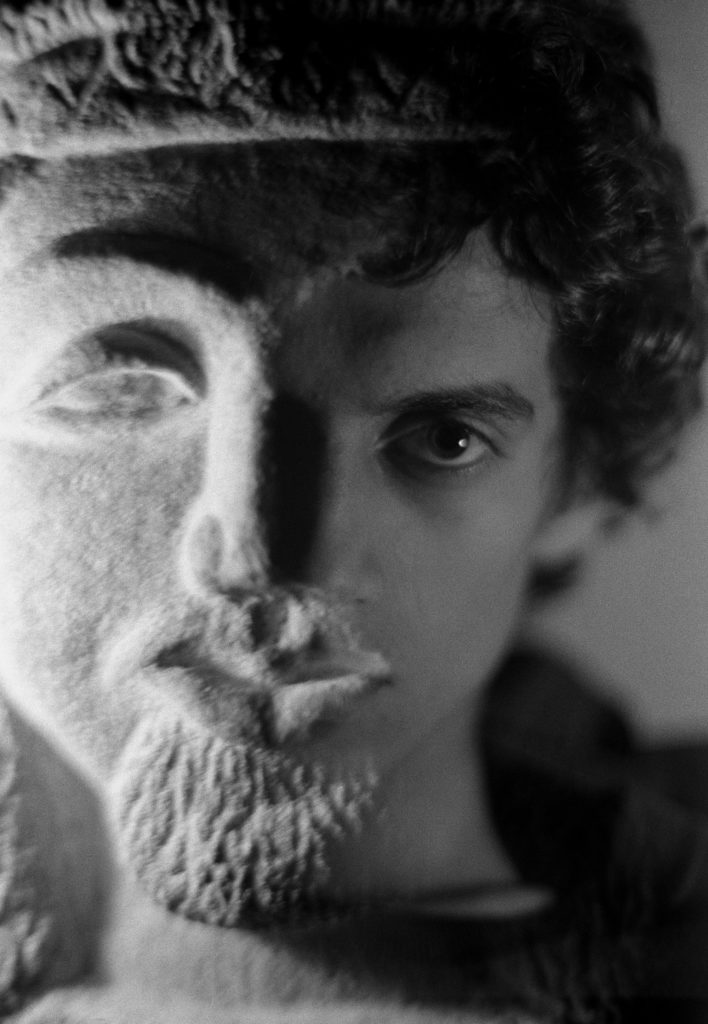

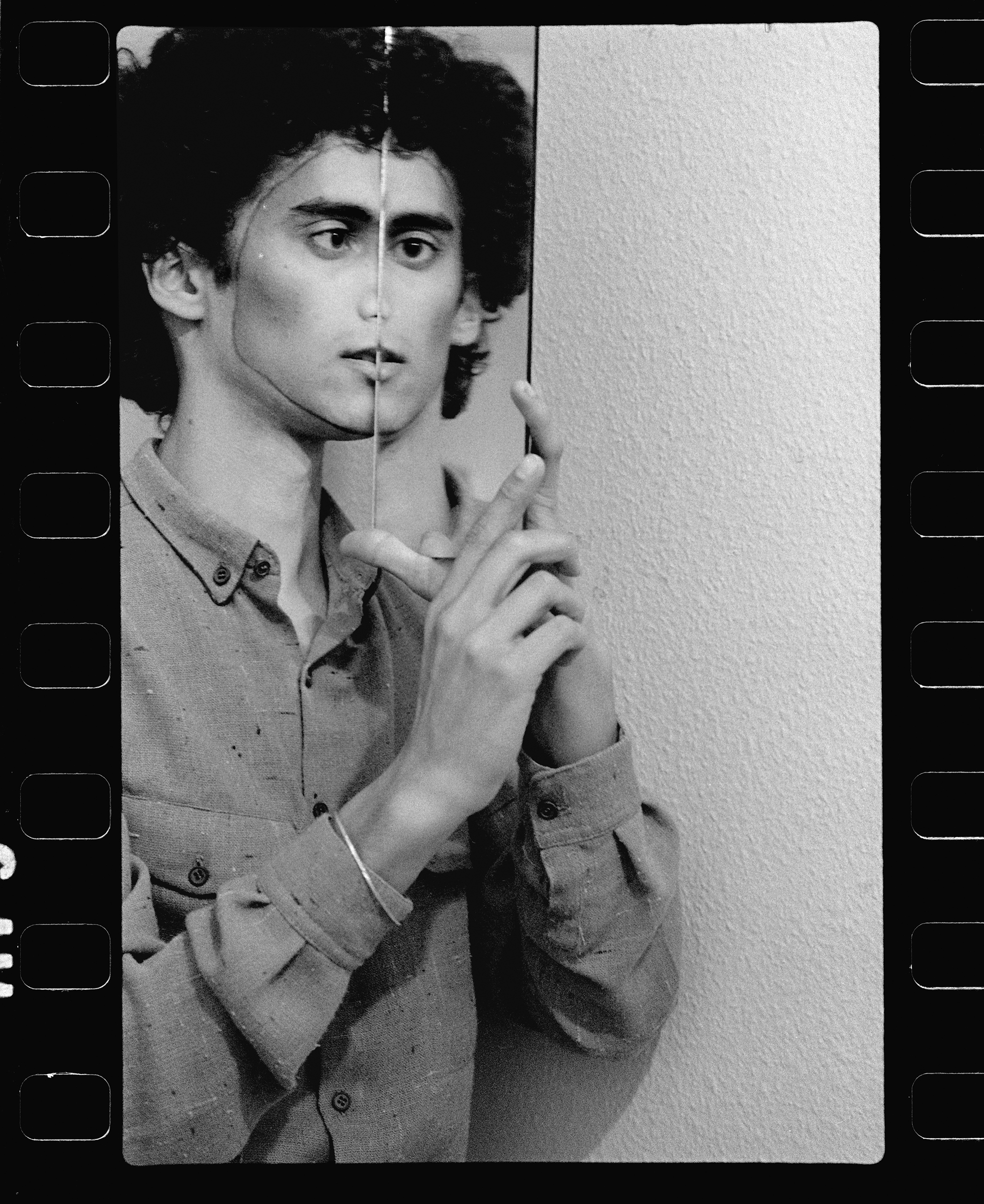

In Eshetu’s videos, biography—what he calls “lived experience”—is never the end in itself. It enables him “to merge two cultures into giving an outlook on something.” Some of his earliest photographs are conceptual touchstones for such a world-blending approach. One double exposure image, Self-Portrait (1975), taken when he was sixteen, shows a quarter of his face juxtaposed with more than half of a mask, depicting a convincing image of a humanoid figure; in Self-Portrait with Mirror (1979), his face is bifurcated with a mirror, giving the illusion of a two-faced figure. Masks became a leitmotif in his early photographs, mostly black-and-white images taken in the years leading up to his studies in London, where he obtained a degree in communication design from North East London Polytechnic in 1981, and just before he took up video art full time. For Eshetu, these early photographs point to “the beginning of an artistic process, where aesthetic and conceptual considerations merge.”

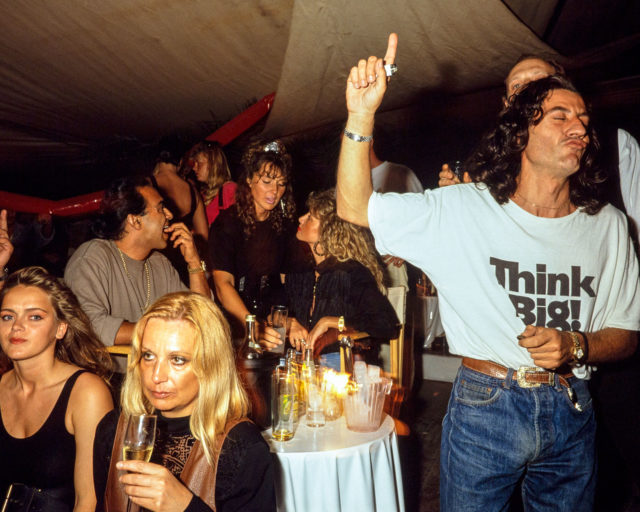

Before he started making videos, Eshetu took photographs of musicians, including Bob Marley and Marvin Gaye. This was how, as a shy teenager, he could come close to his musical heroes. “I learned about photography by photographing musicians live on stage. The performative element was instantly the first material that I was drawn to,” he says. Yet he understood that he was also engaging with the relationship between reality and representation. Thinking about that relationship remains at the core of what Eshetu does; his affinity for music continues to influence his sensibilities. The videos Eshetu makes are notable for their soundtracks, with affecting crescendos and decrescendos indicating emotional charge.

If the arc of Eshetu’s career indicates anything—in his transition from photography to video, from making work for television to installing exhibitions—it is that he is most attentive to video as a nomadic form.

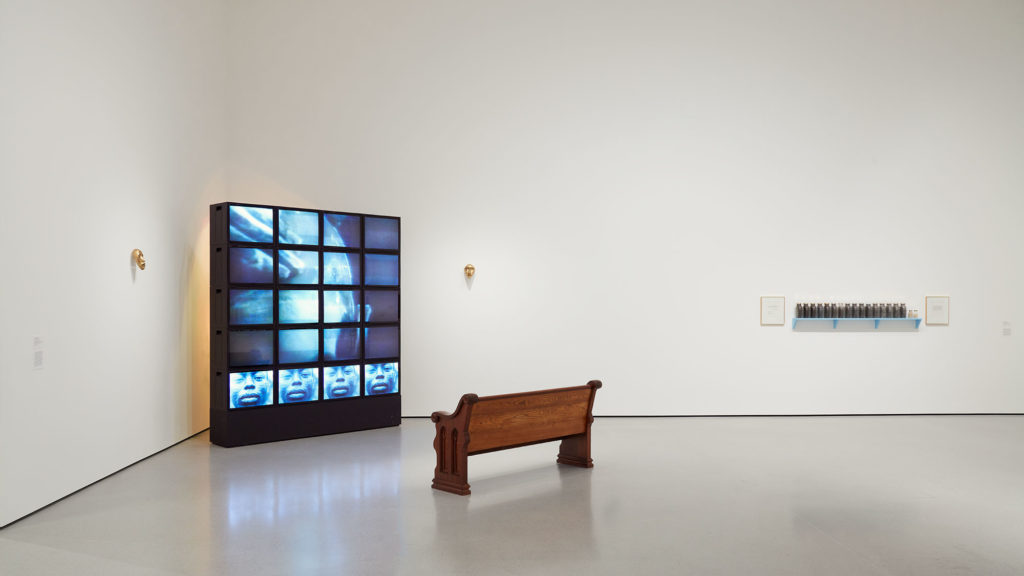

Identity and belonging, as complex propositions in a world of pluralistic knowledge, are underlying dilemmas in Eshetu’s work: the relationship between the self and the non-self. “The non-self,” he says, “is a recognition that you have your self and others have their selves.” He is searching for a non-totalizing worldview. In The Slave Ship (The Law of the Sea) (2015), a video installation evoking the history of slavery, bilaterally symmetrical moving images are shown in a circular frame, as though to indicate the limits of thinking about cataclysmic histories in a linear, straightforward fashion. Other videos by Eshetu achieve a similar destabilizing of the singular view: The Return of the Axum Obelisk (2010) presents a documentation of the restitution of a cultural artifact to Ethiopia by Italy in fifteen screens and Till Death Us Do Part (1982–86), recently presented at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, considers the exponential growth of 1980s media culture in twenty screens.

In a conversation with the late curator Okwui Enwezor, published in The Body Electric (2017), the first comprehensive monograph of Eshetu’s work, the artist notes that he was part of a larger movement by Black filmmakers and video artists in Europe who were questioning regimes of representation. “We were driven by the need to define our identity because we saw that it wasn’t represented on TV or in cinema,” he said. “We had to create it ourselves.” But he was faced with a formal dilemma. How could he identify with the medium? Cinema has a well-documented history, and, by the 1980s, independent filmmaking had also taken off. “I created a bond with the medium itself,” he told Enwezor. “I created an artificial distinction between film and video, as a device, which gave me a path. What started as the malaise of not knowing my identity became what I have somehow tried to solve, and transforming that to making videos has helped me do that.” He was an artist who came of age when television was the central medium to produce videos for, or rebel against, and, in the early 2000s, the Internet was taking over as the central platform for the dissemination of images. By 2002, Eshetu moved away from making videos within the context of television—his work began to be shown mainly in art installations or film festival screenings.

Perhaps his videos are best suited to be shown in art contexts where, at the very least, Eshetu can break “out of the single-monitor mold,” to quote Wulf Herzogenrath, who writes in The Body Electric of Eshetu as one of the pioneers of video art. Eshetu, Herzogenrath says, was part of a generation of artists who “extended televisual monocultures and their linear narrative structure by applying new collage techniques and exploring possibilities by which to disrupt the chronological narratives of the single living-room TV.” Eshetu had studied communication, which, he says, produced a different relationship to film and video making than if he had studied fine arts. With a fine arts perspective, one is concerned with self-expression, while coming from a communication background, “you somehow have the tools of this expression, so you explore those tools.”

Eshetu’s exploration has widened in range and expression, such as in Atlas Fractured (2017), a film produced in two versions for the Kassel and Athens editions of Documenta 14, where he continued to work with masks. The Athens version, projected on a cave wall, shows a slow pan of faces filmed against masks, paintings, and photographs, until, in most cases, they are transmogrified. The film is mesmeric. Atlas Fractured is accompanied by the intermittent voices of a range of thinkers—Carl Jung, James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, Toni Morrison, and Maya Angelou, among others—whose views emphasize the value of knowledge that is receptive to what is unknowable. In the Kassel version of Atlas Fractured, the filmed portraits and footages of historical incidents were projected onto a giant banner that had previously hung at the entrance to Berlin’s ethnological museum. The banner, which showcased masks from each of the museum’s departments, had been cut into sections to be discarded when Eshetu recovered them.

Photograph by Denis Doorly

If the arc of Eshetu’s career indicates anything—in his transition from photography to video, from making work for television to installing exhibitions—it is that he is most attentive to video as a nomadic form, one that is able to take shape under any rubric. In his conversation with Enwezor, he states: “I think there’s an almost comical interplay in my works, through which rules are constantly being set up and broken: a certain liquid quality that makes them fit into various spaces.”

Nearly every year since 1982, Eshetu has premiered or exhibited his videos in and outside Europe, in the major global video art festivals as well as in notable museums and galleries. Alongside artists such as John Akomfrah and Isaac Julien, and members of the Black Audio Film Collective and Sankofa Film and Video Collective, Eshetu is a pioneer—a diasporic African artist who has shown the inexhaustible potential of video art as a primer for the politics and aesthetics of belonging. Yet, he is only beginning to receive broader attention, at least in the United States—in addition to a recent screening at MoMA, Eshetu’s work was included in The Sorcerer’s Burden, a 2019 group exhibition at the Contemporary Austin. Perhaps his significance is most telling in his 2010 work The Return of the Axum Obelisk, which predates the current, widespread cause célèbre of restitution of African artifacts in European institutions as a cultural necessity. He is currently making an essayistic film about the move of the ethnographic collection from Berlin’s Museum of Asian Art to the Humboldt Forum. This controversial new museum in Berlin has served as a kind of laboratory for several of Eshetu’s recent works, including Ghostdance (2020), a video installation for the Gwangju Biennale, filmed, in part, at the Forum.

All works courtesy the artist

Eshetu is elusive on the question about the influence of biography. In 2015, when he was commissioned to produce work on the Non-Aligned Movement, he recalled that he had lived in Yugoslavia, where his grandfather had been Ethiopia’s ambassador in Belgrade. He went to the Museum of Yugoslav History, delving into the extensive photography archive of the former Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito, in search, as he put it later, of “oblique traces of biography, tangential associative thoughts, fragments of forgotten memories, and unwritten personal histories.” The result is The Mystery of History and His Story in My Story (2015), an essay of forty-four photographs. One of the most intriguing images shows six sailors facing a map of the African continent. Their stance seems like a synecdoche for Europe as it observes Africa. It equally reflects the fusion of Eshetu’s bicontinental family history with a grander one, a confluence from which he sprung as an artist. “This idea of biography,” he says, “is not anything really to do with me. It’s to do with a hypothesis of a world vision.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 244, “Cosmologies,” under the title “Theo Eshetu: Infinite Screens.”