Thomas Ruff: Photograms for the New Age

For more than thirty years, German photographer Thomas Ruff has investigated the grammar and structures of photography, through his many celebrated series, Sterne/Stars (1989), maschinen/machines (2003), and cassini (2008)—to name just a few. After turning away from straight photography in the mid-1990s, Ruff has worked mainly with found imagery culled from a variety of sources—from print catalogs and scientific negatives to the Internet, from which he purloined pornographic images for his nudes series, which he began in the 1990s.

More recently, he has turned his attention to 3-D imaging software to continue his investigations of the medium. For his newest project, Ruff has taken up a study of the photogram, updating the form for the digital era by creating his works in a 3-D digital studio environment and outputting the resulting images in the large scale he tends to favor. Michael Famighetti spoke with Ruff, who is based in Düsseldorf, by phone in February as he finished work on this new series in preparation for its debut at New York’s David Zwirner Gallery .

This article is included in the Summer 2013 issue of Aperture, which is organized around the theme of “Curiosity.” Thomas Ruff is also featured in The Düsseldorf School of Photography (Aperture, 2010).

Michael Famighetti: Can you tell us about the process behind this new body of work? What were you after when you decided to produce photograms in a digital studio?

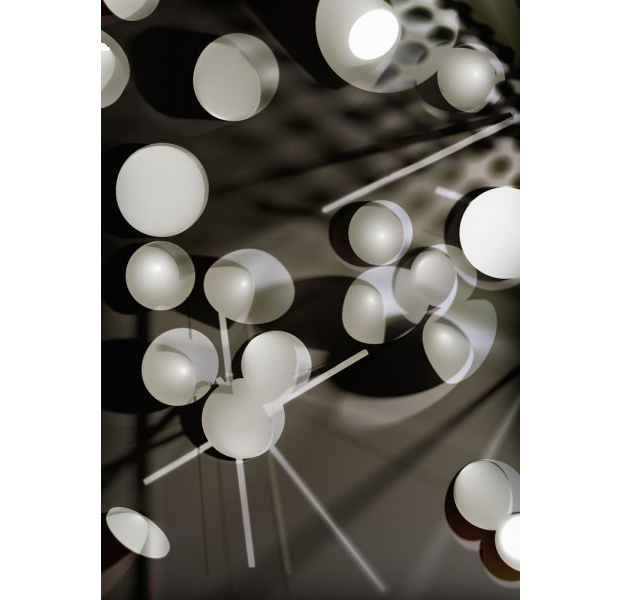

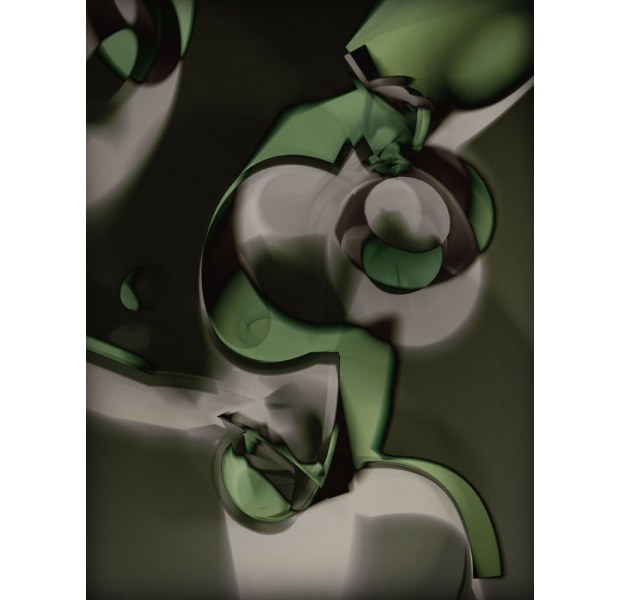

Thomas Ruff: The decision was quite simple. I have two photograms by Art Siegel in my collection and I passed by them again and again. Two years ago, I had the idea to begin making some of my own photograms. When I started analyzing how these photograms were made, I realized that it would be quite complicated; photograms are limited to the size of the paper and to the limitations of the black-and-white darkroom. You don’t have much color—only a brownish or bluish tone. And the other thing was if you put objects on the photographic paper and remove them, and then realize that these objects would have been better shifted to the left or the right, you have to start over again. You need a lot of luck to get a good photogram, so I considered how could I do it in a different way. I had already been working with a 3-D software on my series zycles, so I thought, maybe this is the right tool to try with the photograms. I developed a virtual setup: the paper on the bottom, and the objects—lenses, chopsticks, spirals, paper strips, all kind of objects—I put on the paper. There is a camera above, recording the paper, and then I set the lights with different colors.

MF: You have continuously investigated a range of mostly representational photographic types: the jpeg, the nude, the scientific image. What attracted you to the photogram as a form?

TR: The photogram is a kind of “pencil of nature.” It’s cameraless photography—you don’t see the objects but only shadows, which reminds me of Plato’s cave. It’s a very vague photography; you can’t recognize things very clearly but you recognize something. Soon I realized if I use too much color, it doesn’t look like a photogram, it just looks strange and abstract.

MF: The images here are reminiscent of László Moholy-Nagy’s experiments with color photograms from the 1930s. How active did you want such historical references to be?

TR: The goal was really to make a kind of “new generation” of the photogram. So it still should look like a photogram, but not old-fashioned. I tried different types of photograms: some with lenses, some with spirals. I want to experiment more with the possibilities of this kind of software to create different kinds of images. I can imagine that Moholy-Nagy would have been absolutely glad if he could have used my technology! You can do so much more than with the limitations of the analog darkroom. I am sure he would have loved the software.

MF: The “types” of photograms here are entirely determined by the objects?

TR: Yes, mainly by the objects. If you look at Moholy-Nagy’s photograms they show different typologies within the photograms. I wanted to make variations of these different types.

MF: Photograms are usually quite small—they are limited to the size of the paper available, as you mentioned. Will these images be on par with the usual large scale of your work?

TR: Yes, they will be really big.

MF: Why is large scale important?

TR: First of all, I wanted to break the world record of the size for the photogram! [laughs] The early photograms, from the 1920s and ’30s, are quite small, more postcard size. Photograms from the New Bauhaus school—by Art Siegel and his colleagues, for example—are approximately fifty by sixty centimeters. I work with the large format; I like the physical presence of the big size.

MF: You mentioned the connection between this new body of work and your zycles series, computer-generated abstract line drawings based on algorithms. Throughout your career you have worked in strictly delineated series. Is it common for one series to bleed into the next?

TR: Yes and no. I am using the same software, the same techniques—but one series doesn’t emerge from the other. It’s more like you have a Leica, and then you have a Linhof: a 4-by-5 camera, and then an 8-by-10 camera. They are just different tools, or cameras, or techniques. The output looks completely different.

MF: Much of your work investigates “systems” and the role of genre in photography. You’ve worked with many forms of found photography, from catalog to online imagery. Considering how much photography has transitioned in recent years—this explosion of imaging—do you see new systems and genres emerging?

TR: I see photography as a very classical medium, with of course all kind of genres—portrait, abstract, science photography, and so on. What I am also interested in right now is the negative, since it seems that it is going to disappear soon. When I ask my nine-year-old daughter, “What’s a negative?” she can’t say, as she knows only digital photography.

“Polaroid? What’s that?” she asked me some time ago. What interests me is the outcome of all these different kinds of photography and how they change our lives and our perception of the world. I just turned some photographs that I own into negatives, and they look strange. My interest in this process comes from working on the photograms—I make reverse photograms. And you still have these strange, old-fashioned darkroom techniques, like solarization, which I now also practice in the photograms series.

MF: How do you see photograms, or abstract images, shaping our perception of the world?

TR: The photograms are not so much about the perception and influence of photography in our daily lives. Maybe I just want to recall that artists used techniques in photography that enabled them to make completely artificial and abstract photographs and that these techniques are, unfortunately, nearly forgotten.

MF: You’ve taught at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where you also studied. How does your interest in the history and evolution of photographic technologies come into play in the classroom?

TR: I’ve used a lot of different photographic techniques in the past thirty years. I realize there isn’t just one way to take a photograph, there are a thousand different ways—and that’s what I’ve taught the students. They should not insist on their beautiful Leica, or their Hasselblad, or whatever they use. The technique must result from the idea that you have—and you may have to develop your own technology to bring out the images. I’m not much interested in “straight” photography anymore. It has been practiced for more than 150 years, and most of it is too conventional. I’ve always wanted to go beyond the limits.

MF: But you are interested in photographic conventions. Why?

TR: I think photography is still the most influential medium in the world, and I have to deconstruct these conventions.

MF: Do you ever take pictures, in the traditional sense?

TR: The last photographs that I took in the traditional way, with an 8-by-10 camera and negative film, were architectural photographs of my studio some months ago. And, of course, if an idea for a new series requires a traditional analog photograph, I will use the camera again.

MF: Could you talk about the role of research in your work? Where does a project begin?

TR: If I see an image that attracts, upsets, or astonishes me—one that stays in my mind for a long time—I begin working. This is the starting point of the research: I try to find out how the image was created and in what context—historical, political, or social—the image belongs. After clarifying these questions I begin to create “my own” image, the image I have in my mind, the image that was triggered by the image I saw. Sometimes it can be done in a straightforward way, with a camera, but sometimes you need to reflect on how you can manage to make this technically. For example, when I had the idea of photographing the night sky, I realized that with my small telescope, I had no chance of getting high-quality images of stars, so I looked for an observatory with a big telescope where I could take the photographs myself. But they wouldn’t let me in. So I had to give up the idea of being the author of the photograph, and worked with large-format negatives from the observatory’s archive.

MF: It’s been written that when you were in high school you wanted to be either an astronomer or a photographer. Your cassini series connects the two occupations.

TR: I have an affinity for astronomy, so from time to time astronomical issues show up in my work. The cassini series consists of images of Saturn, its moons and rings, taken by a machine camera within the Cassini spacecraft. They are black-and-white photographs with an abstract quality that I really like. To highlight the abstraction, I colored these photographs so that they resemble a kind of “post-Suprematist” image.

MF: You’ve spoken of your interest in the writings of Vilém Flusser, whose ideas about imaging, written in the 1970s and ’80s, feel prescient today.

TR: [Flusser’s 1983 Towards a Philosophy of Photography] is a book I read twenty years ago. He was writing about the shifting of photography. There are a lot of different photographs, and different photographs have different intentions. Fine art, medical, propaganda, and of course the most influential image-production machine is advertisement. This transformation, let’s say, of the scientific photography into the art world, or advertising photography into politics (as seen in the last U.S. election)—this modification of images from one intention to another brings about interferences. The image, and the meaning of the image, changes.

MF: This notion of shifting contexts—and thereby shifting meanings—is central to your work. This is true with your nudes series, your first using Internet imagery. How does your image-collecting process work?

TR: I have a particular curiosity; I see things, I collect them, with no intention or without knowing what to do with them. I just keep them, because they trigger something within myself. A couple of years later, maybe even ten years later, these things appear in my mind again and lead to a new body of work. There’s no straight line or conscious scheme of collecting. It could be any kind of image—it’s just that I’m attracted to it.

MF: Does the medium continue to surprise you?

TR: No, not really. But of course I’m always happy when I see a new, never-before-seen example of a photograph. An image is just an image—it all depends on what you do with it.