Two Photobooks Consider the Pervasive Fantasies of Whiteness

On February 23, 2020, Ahmaud Arbery, a twenty-five-year-old African American man, was shot while running in a suburban neighborhood outside of Brunswick, Georgia. A video recording of the incident shows two white men following him in a pickup truck, confronting him, and firing their guns three times. Arbery was dead when police arrived. No immediate arrests were made, and for seventy-four days the men remained free. Only after the release of the video sparked public outcry were they charged with murder.

Arbery’s killing has prompted anguished talks about the peril faced by African Americans in “running while Black” or, more bleakly still, “living while Black.” But the initial reluctance of some Georgia authorities to charge the men, even with the existence of potentially damning video footage, is also a devastating illustration of what the photographer and writer Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa calls “the governing equation of whiteness to innocence.”

Courtesy the artist and Loose Joints

Being white, as Daniel C. Blight reflects in his timely and perceptive book The Image of Whiteness: Contemporary Photography and Racialization (2019), is about much more than skin color. It is a “stubborn and often invisible power structure,” a ubiquitous ideology of domination, privilege, and violence that hides in plain sight as a default “natural identity” for white people. It is also a way of seeing the world. And as Blight observes, the camera has been deeply implicated in the promulgation of the white gaze virtually since its invention in the nineteenth century. The Image of Whiteness features excerpts from projects by various artists, such as Paul Mpagi Sepuya and Hank Willis Thomas, alongside insightful dialogues with key thinkers on race, including the writer Claudia Rankine and the philosopher George Yancy. Blight aims to explore how the white imaginary is developed and perpetuated across Western culture and to also consider how photography can help reveal whiteness “for the set of representational fictions that it is.”

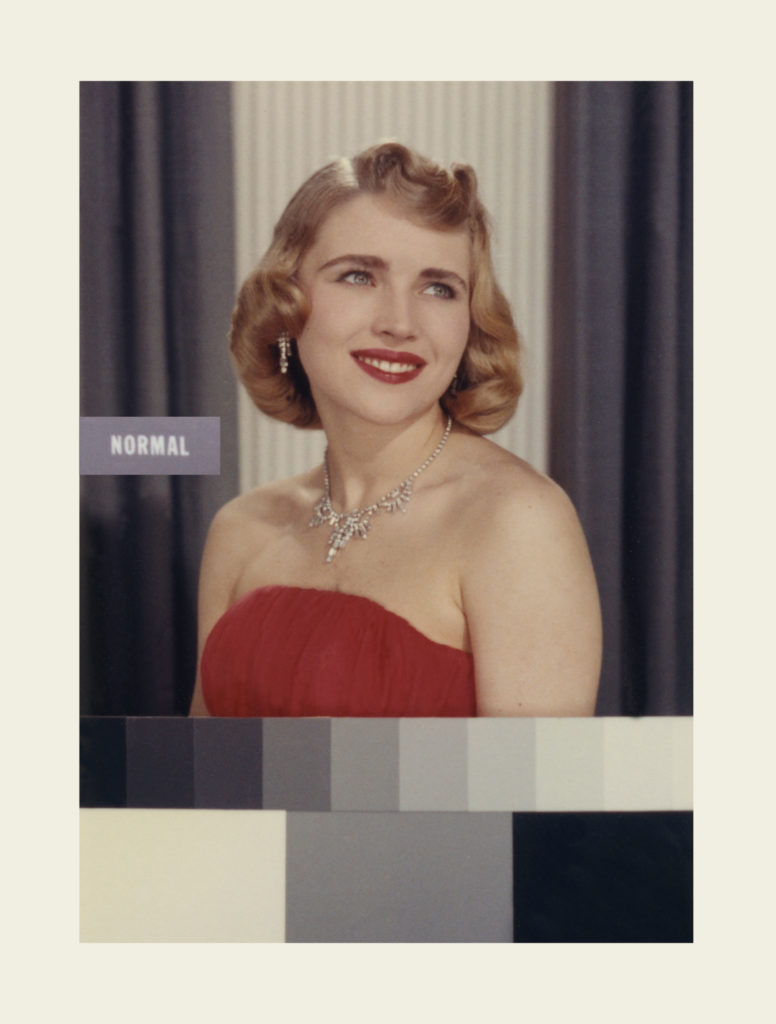

To those ends, the book presents Michelle Dizon and Viêt Lê’s project White Gaze (2018), which appropriates archival imagery from National Geographic, unpacking and disrupting the visual language of racial hierarchy encoded in each picture. In another contribution, Broomberg & Chanarin look to the loaded history of Kodak’s Shirley test cards and the false equivalence of whiteness with universality that they fostered.

Courtesy the artists and Lisson Gallery, London and New York

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Some artists whose works appear in the book explore race through strategies of erasure. Ken Gonzales Day digitally removes the hanging bodies of Black or Brown victims from archival pictures of lynchings that took place in the United States. Nate Lewis obscures the faces of people of color from news footage of Trump rallies. The result of these works is to turn attention to the white figures in the images—the grinning spectators jeering at the (now absent) dead body, and the Trump supporters engaged in what appears to be a verbal assault on Black onlookers. Both projects offer vivid proof of Yancy’s observation that whiteness is a “parasitic” condition that survives by creating a menacing racial “other”—the Black body—on which it can assert sovereignty.

White power and privilege are also the governing themes of Buck Ellison’s recently published monograph Living Trust (2020). Ellison’s photographs, a selection of which appears in The Image of Whiteness, seem to document the habits and tastes of the white upper-middle class. There are photographs of lacrosse matches and Range Rovers, a young man in performance fleeces of various colors, and Christmas-card portraits of well-groomed families. But these are mostly artificial scenarios constructed by Ellison using paid actors and models. The images highlight how wealth has historically enabled members of the upper socioeconomic classes to present a veneer of bland respectability to the world, irrespective of their private prejudices.

Ellison devotes a section of the book to a series of family portraits purportedly showing Betsy DeVos, Donald Trump’s controversial secretary of education, and her brother, Erik Prince, founder of the notorious private military company Blackwater. Few private pictures of the family exist in circulation, and in lieu of these, Ellison presents his own confected portfolio. A group picture, The Prince Children, Holland, Michigan, 1975 (2019), shows four blond siblings lounging in a 1970s-era living room decorated with mahogany furnishings and characterless paintings, the room displaying not so much wealth but the Protestant rectitude of the Prince family’s strict Calvinist beliefs. The imagined portraits strive to convey normalcy, but there’s an unsettling undercurrent to them that hints at what F. Scott Fitzgerald’s narrator in The Great Gatsby calls the “vast carelessness” of the rich.

Courtesy the artist and Loose Joints

In the image Erik with Kitty, Blackwater Training Center, Moyock, North Carolina, 1998 (2019), Erik, as a young man yet to found a security force implicated in the massacre of seventeen Iraqi civilians, sits on the grass, playing with a kitten while sporting tactical pants and a bulletproof vest. Another photograph, titled Dick, Dan, Doug, The Everglades Club, Palm Beach, Florida, 1990 (2019), shows four men out on a manicured golf course: Two golfers haggle over the position of the ball near a hole. The third golfer has his back turned and is pissing on the green. An unnamed caddy looks on impassively.

Ellison’s photographs describe whiteness as its own paradisal domain—a world where people of color are banished from sight, and where actions have no visible consequences. It is a fantasy, albeit one that some, such as the killers of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and far too many others, seem to aspire to as a reality.

This article was originally published in Aperture, issue 240, “Native America,” under the column “Viewfinder.”