The Limits of Representation

Victor Burgin tests the connection between ideas and action.

Victor Burgin, Still from Mirror Lake, 2013. Digital projection, 14:37 minutes

Courtesy the artist and Cristin Tierney Gallery, New York

No one is associated more forcefully with a cool academicism than Victor Burgin. His highly theoretical writing, as well as his pioneering use of politically inflected text in photography and video, has been a hallmark of Conceptual art since the early 1970s. However, Conceptual art, in foregrounding its ideas in self-referential forms, is usually understood as devoid of energetic, activist politics. In a recent review in Artforum of John Baldessari’s exhibition at Sprüth Magers in Los Angeles, for example, Nicolas Linnert makes a shortsighted attack on conceptualism, “What exactly is gained today by continuing to exploit the capacity of images to free themselves from meaning? To avoid a stance?” Linnert suggests that only representational art has any worthwhile affective power, thereby precluding artists like Sarah Charlesworth—who worked with found images and abstraction, often simultaneously—from being considered socially-engaged. Nevertheless, it’s a thought experiment worth applying to Victor Burgin’s concurrent shows shows in New York at Bridget Donahue and Cristin Tierney. What is at stake in both presentations is whether Conceptual art can transcend hyperintellectual concerns and speak to activist issues, and whether artists can express their politics in forms other than pure representation.

Victor Burgin, UK 76 (detail), 1976

© the artist and courtesy Bridget Donahue, New York

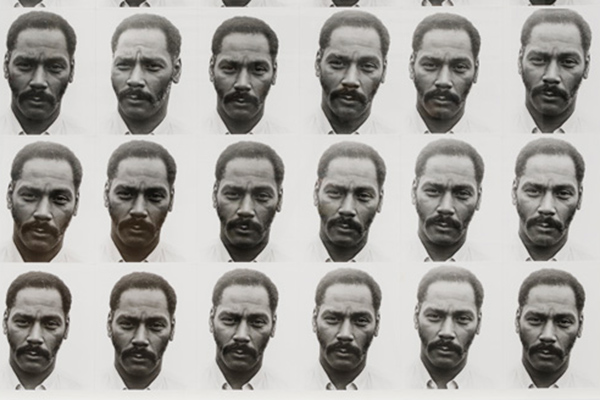

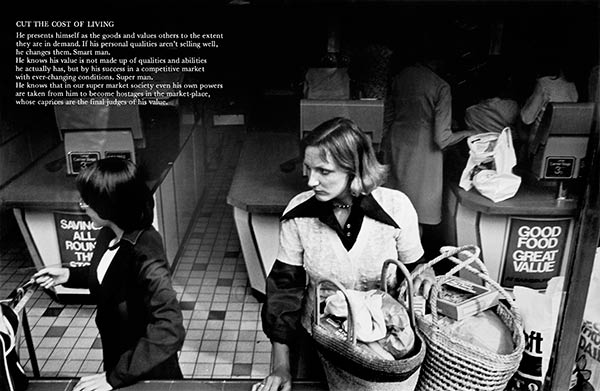

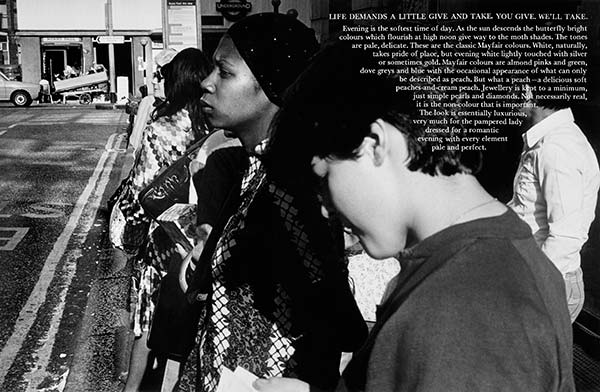

Burgin’s exhibition at Bridget Donahue is comprised of archival inkjet prints from the series UK76 (1976) carefully wheat-pasted to the wall. Each photograph, in characteristic Burgin style, consists of text—some found, some composed by the artist, some deadpan, and some florid—placed above an image, each wonderfully reminiscent of film noir in their monochromatic grandeur and allusions to surveillance and violence. Though straightforward, these texts have a lyrical and poetic quality that, no matter their source, becomes strangely poignant. The texture of the paste also lends a corporeal element, as if a very thin skin has affixed the images; in a reference to the original presentation of UK76 four decades ago, the images will be scraped from the walls when the exhibition closes.

Victor Burgin, UK 76 (detail), 1976

© the artist and courtesy Bridget Donahue, New York

One photograph depicts a woman at a bus stop with the same disinterested glance that so interested Walker Evans in his Subway series (1938–41) and Cindy Sherman in her Bus Riders (1976/2000). The text watches over the scene like a forlorn vulture: “Evening is the softest time of day. As the sun descends the butterfly bright colours which flourish at high noon give way to moth shades.” This rapturous prose gives way to the sales points of an advertorial. “The look is essentially luxurious, very much for the pampered lady dressed for a romantic evening with every element pale and perfect.” But, are the unsubtle allusions to whiteness (“pampered lady”; “pale and perfect”) incongruous with the photograph’s black, presumably working-class protagonist? Like any advertisement, the first instinct is to read the text and image as related, despite their obvious dissonance. Yet this isn’t some valorization of the working class, or an elevation of the humdrum daily commute to the status of poetry. We are swept up in beautifully saccharine imagery—we believe the drama—until we discover that the directive to feel moved comes not from true emotion, but from advertising.

Victor Burgin, Still from Prairie, 2015. Digital projection, 8:03 minutes

Courtesy the artist and Cristin Tierney Gallery, New York.

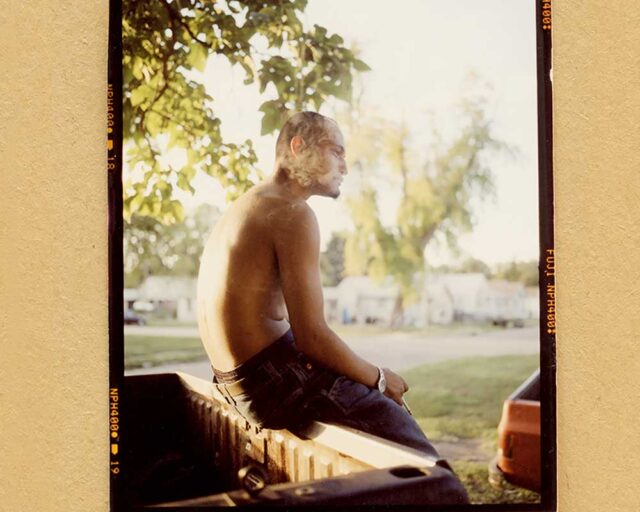

Mirror Lake (2013), one of two digital projections on view at Cristin Tierney in Burgin’s exhibition Midwest, has a similar emotional impact, if more melodramatic. It opens with an interior shot of a train car, a favorite film setting from Alfred Hitchcock to Lars von Trier. A story of interconnected lives enacted by the theft of Native American land ensues, based only on a series of dour, almost ethnographic shots that receive their resonance from applied text. Burgin presents quietly rhapsodic words that emolliate the silence: “There is enchanter’s nightshade and maidenhair fern, blue marsh violet and marsh marigold, orange jewelweed and sarsaparilla, creeping snowberry and wintergreen… The Winnebago once lived here.” There is no joke, no sardonic twist—only a serious narrative (be it fact or fiction) delivered with harrowing and compelling sentimentality.

Victor Burgin, Mirror Lake, 2013. Installation view at Cristin Tierney Gallery, 2016

Courtesy Cristin Tierney Gallery

Burgin allows us to think emotionally and emote intellectually; the distinction between conceptualism and social engagement is no longer a useful division. While his work may not incite protests, from these two exhibitions there emerges an active, politically inflected photographic formalism: the viewer must take a stance, simply by bearing witness to his interplay of feeling and imagery. Revealing Conceptual art’s capacity for excess, emotion, and affect, Burgin’s work is a study of how we relate to traumas both personal and social.

Victor Burgin: Midwest is on view at Cristin Tierney through October 22, 2016. Victor Burgin: UK76 is on view at Bridget Donahue Gallery through November 6, 2016.