Vision & Justice: Around the Kitchen Table

Five voices from the fields of theater, photography, and art history to reflect on one of Carrie Mae Weems’s most iconic projects.

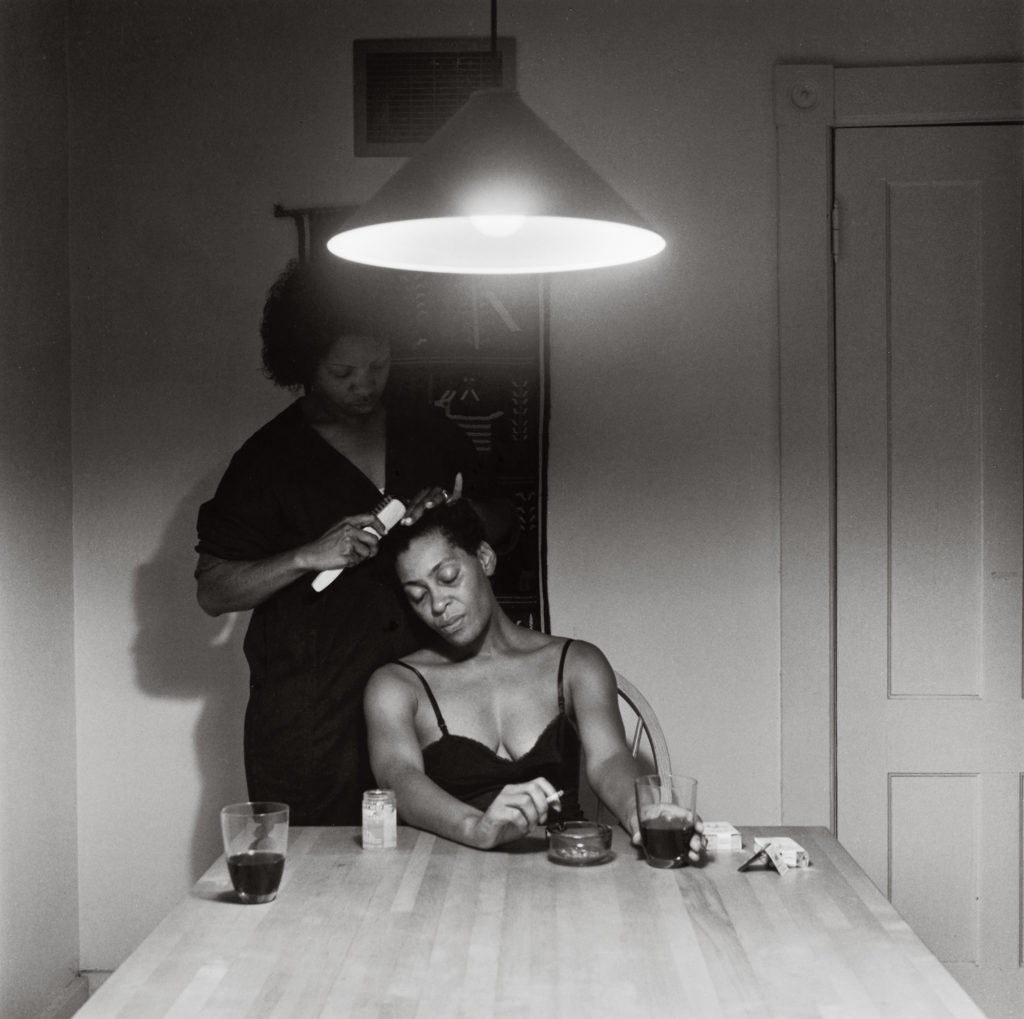

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Woman and daughter with makeup), 1990

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Carrie Mae Weems combines performance and narrative to dynamic effect. For the “Vision & Justice” issue, Aperture invited voices from the fields of theater, photography, and art history to reflect on one of her most iconic projects.

Robin Kelsey

Kitchens and streets. You could write a history of the twentieth century through that pairing. If the city street is a place of random encounter, of hustle and protest, the kitchen is a place of intimate habit, of sharing and aroma. Emotional distance is routine on the street, but excruciating in the kitchen. Yet if such a history is worth writing, it is because these two places are by no means discrete. The street presses into the kitchen, stocking shelves and burdening conversations. The kitchen is a delicate sanctuary, vulnerable to the threat of violence, and to the prejudice and fear that abound outside. But the kitchen has a subtle power of its own. It bears an improvisational capacity to bind subjects in shared experience, and to restore and refashion them in the midst of struggle.

In the Kitchen Table Series, Carrie Mae Weems takes these issues on with verve. The second photograph in the sequence depicts the protagonist drinking and playing cards with a man. A bottle of whiskey, a pair of mostly emptied tumblers, a dish of peanuts, some discarded shells, and a cigarette pack: these things constellate into a still life, lit by the glowing bulb above. The peanuts, cigarettes, and whiskey tie the kitchen into a larger economy and its history. As agricultural products grown mainly in the South, they mix into this leisurely moment signs of labor, suffering, and migration. A history of many streets, of rural South and urban North, has seeped into the scene, which recalls, in smoky black and white, earlier meditations on exodus and hope.

The streets of New York also arrive via the photographs on the back wall. At the center is an image of Malcolm X at a rally. The photograph was taken in 1963, but the popular poster featuring it dates to 1967. To the right is a familiar photograph from 1967 by Garry Winogrand, showing a light-skinned woman and a dark-skinned man in Central Park carrying chimpanzees dressed like children. Using racism and fears of miscegenation to make a joke, the Winogrand photograph exemplifies the troublesome role that humor plays in both exposing and perpetuating stereotype. These icons of the 1960s, blurred in the kitchen by a cigarette haze, elicit memories of turbulent race relations on New York streets. By enfolding these icons in a Roy DeCarava–esque 1950s mood, Weems layers the photograph with traces of formative decades.

Invoking these layers in 1990, Weems raises questions concerning their legacy for art and life. Consider the subtle play of mouths and hands linking the central poster to the foreground figures. While Malcolm X points toward the unseen crowd and seems on the verge of forcefully speaking, the protagonist holds her cards in her left hand while curling her right in front of her mouth. Her male companion offers a mirror image, cards in his right hand, his left holding a cigarette to his lips. In the kitchen table scene, the blazing public oratory of Malcolm X has turned inward. With cards held close, canny glances directed sidelong, mouths hidden, these players work the interior. The politics of the street have folded into a private circuit, an exchange predicated on a shared history and bound by the rules of a game. Although we can read the signs, we remain at the far end of the table, uncertain of the rules, and not privy to this intimacy and its unspoken content.

Robin Kelsey is Shirley Carter Burden Professor of Photography at Harvard University.

Katori Hall

In my world, the kitchen table ain’t never been just for eating. Friday night “fish frys” segued into Saturday night hair fryings on the weekly. Till this day, I still have nightmares about the hot comb. I remember Mama would tell me to hold my ear down, and my body would just recoil, bracing for my skin’s possible kiss with a four-hundred-degree iron. The worst was when she told me to duck my head down so she could snatch my “kitchen.” Honey, let me tell you, it is a brave girl who submits the nape of her neck to that fire. Perhaps it is the reason why the delicate hairs that stake claim there have themselves been called “the kitchen,” as they are so often tortured into submission in the space that bears their name.

As barbaric as this nighttime ritual of singed hair may seem to some, it is the tenderness served up to us tender headed that has left its indelible mark. The kitchen is a place to be burned, but it is a space to be healed as well.

In this image from the Kitchen Table Series, Carrie Mae Weems gives viewers the privilege to witness this remarkable, ordinary-extraordinary ritual. Playing that everywoman we all have been at one time or another, the photographer herself sits in a black slip, cigarette just a-dangling, head cocked to the side, seeking solace against the belly of a kitchen beautician. Is it a sister? A mama? An auntie? A lover? Whoever we imagine, this image of blissful domestic intimacy reminds us all of the women who, while scratching that dandruff right on out, offered an ear as a cup for our tears. We couldn’t afford to sit on a therapist’s couch, and—even for those who could—Vanessa down the way could give you a mean Kool-Aid tip and advice on how to give that usher cheating with-a yo’ husband Heyell. The beautician’s chair in that kitchen was a healing throne. Fixing food … fixing hair … fixing poor souls.

Katori Hall is a writer and playwright from Memphis, Tennessee. Her recent plays include The Mountaintop and Hurt Village.

Salamishah Tillet

When my daughter, Seneca, was a nine-month-old, she would crawl over to the mirror every morning. There, she greeted herself with a wide, near toothless smile marked by such gusto that I wasn’t quite sure if she knew who was staring back at her.

In 1949, French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan famously diagnosed this moment of child self-recognition as the “mirror stage,” that critical phase of human development in which the baby sees herself as distinct from—not, as she previously assumed, one with—her mother. He theorized it was the collapse of the human ego, our first real trauma, that led us to forever construct everyone else as the “other” as we learned to live as fractured selves.

But what if Lacan was wrong? At Carrie Mae Weems’s kitchen table, we witness another mirror stage: a mother with a lipstick in hand fixed on herself, her young daughter in a miniature version of the same pose. Even without looking at each other, they synchronize this gender performance. A mother who teaches her girl-child the fragile ways of femininity even as the mother does not fully embrace or embody these same terms of womanhood for herself.

But that is my cursory read. Weems’s genius has always been to reveal, consistently and with newness, in familiar and foreign settings, what poet Elizabeth Alexander calls “the black interior,” a vision of black life and creativity that exists “behind the public face of stereotype and limited imagination.” To tap “into this black imaginary,” Alexander writes, “helps us envision what we are not meant to envision: complex black selves, real and enactable black power, rampant and unfetishized black beauty.”

In this context, then, their self-gazing is a reparative act. A mother and a daughter (and we, always we) learning a far more valuable lesson: to be able to see each other, their black woman and black girl selves, in spite of the gendered and racial invisibility into which they both were born.

I still see glimpses of Weems’s radical vision when my now three-year-old daughter looks in the mirror, not every day and without a toothless grin; she has a slyer, wiser smile. Reflected back is a child who hasn’t been taught to un-love herself, who hasn’t yet been asked, as W. E. B. Du Bois once wrote of his boyhood, “How does it feel to be a problem?”

Instead, she is in process, an unfolding subjectivity, still waiting to live out the many possibilities of black interiority that Weems’s Kitchen Table Series has already given us.

Salamishah Tillet is Associate Professor of English and Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

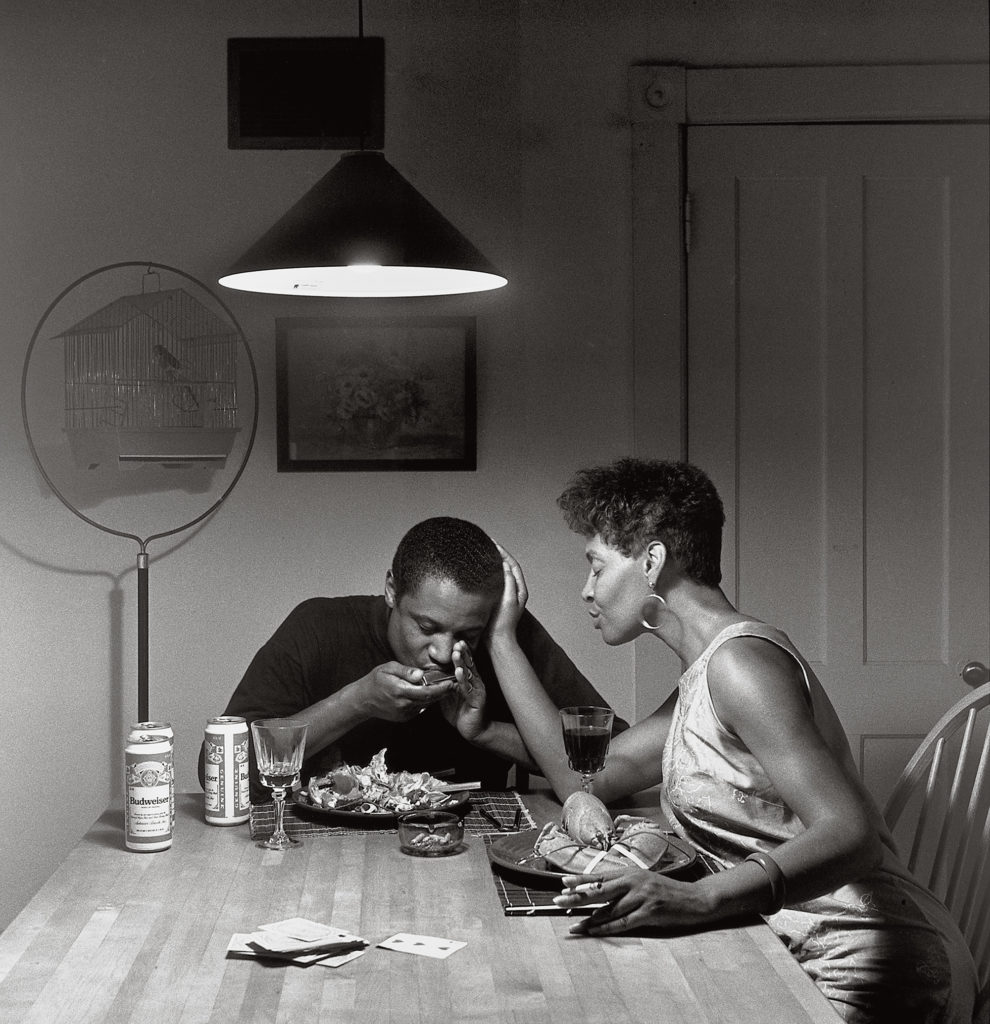

Dawoud Bey

Oh, the blues ain’t nothin’

But a woman lovin’ a married man

Oh, the blues ain’t nothin’

But a woman lovin’ a married man

Can’t see him when she wants to

Got to see him when she can

“The Blues Ain’t Nothin’ But … ???”

—Georgia White

Looking at this photograph, one can almost hear it. And what one hears is the blues by way of the harmonica being played. The harmonica wasn’t always considered a blues instrument, you know. It was originally a German instrument, used to play traditional waltzes and marches of a decidedly European persuasion. But once the small instrument found its way to the southern part of the United States, and the black communities and musicians there, well … you know what happens when black folks get their hands on something. It becomes something else, molded to the idiosyncratic, emotional, and cultural shape of black southern tradition. In this case, an extension of black expressivity of a vernacular kind, played within the context of a music that came to be called the blues. Originally meant to be played by blowing into it, the harmonica, when it reached the black South, underwent a transformation.

Instead of simply blowing, black southern harmonica players realized that sucking at the instrument, and the reeds within, yielded a more plaintive sound and a different pitch, one more akin to the bending of notes on a guitar—the better to exact a more human, expressive tonality from the instrument. In so doing, black blues harmonica players found yet another way to bring an individual sense of black vocality to an instrument not necessarily made to speak that particular musical language.

The blues, of course, are about finding the good in the bad, playing through the pain to extract the joy and the lesson within. The scenario presented in this Carrie Mae Weems photograph from the Kitchen Table Series contains all of the tensions and dualities embedded in the blues: His succulent lobster is completely eaten, while hers remains untouched. His glass is almost empty, while hers is full. Eyes closed, they are both lost in the shared moment. As he plays, she sings and touches his face tenderly, cigarette dangling from her free hand. A man and a woman, lost in a beautiful, poetic, and forever enigmatic moment.

Dawoud Bey is a photographer based in Chicago.

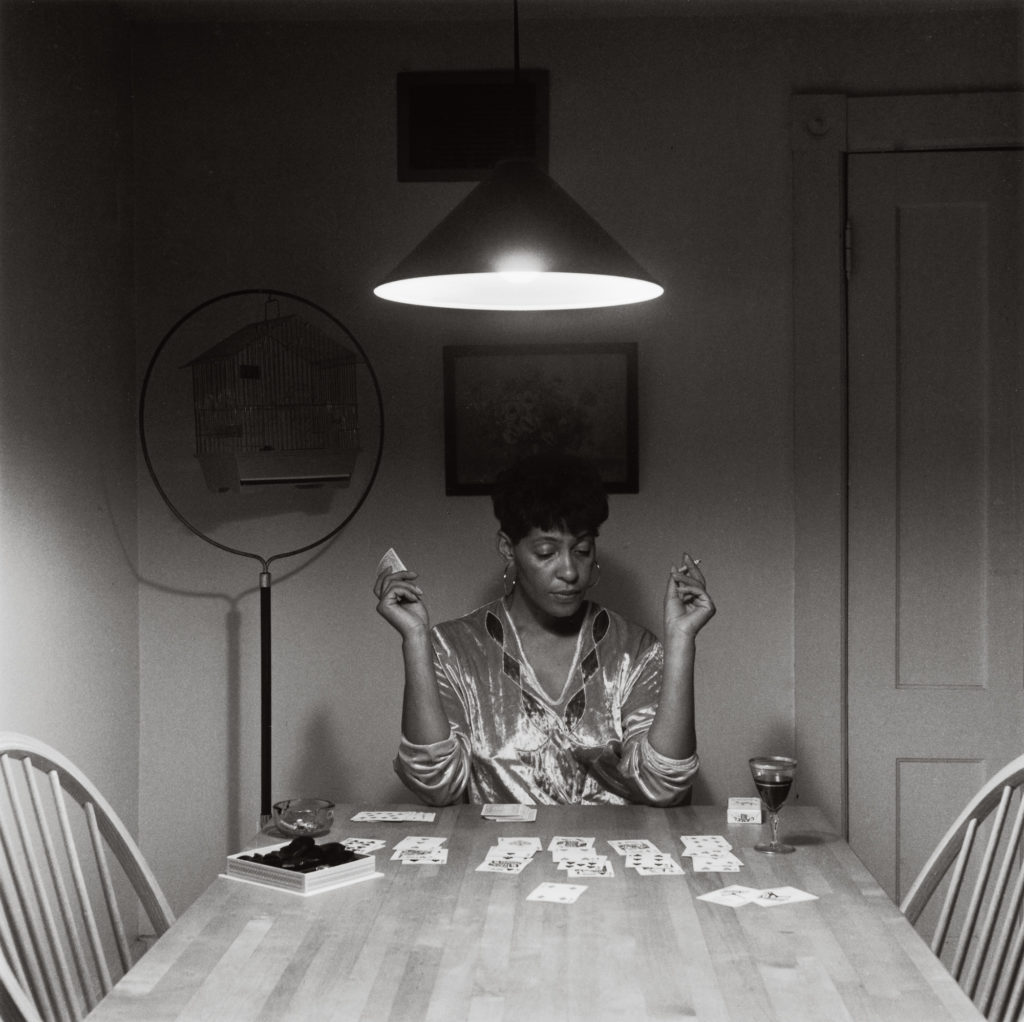

Jennifer Blessing

Carrie Mae Weems’s landmark Kitchen Table Series opens with a photograph of a woman caught between her reflection and a faceless phantom of a man. The final chapter of that unfolding story, the denouement after a violent off-camera climax, begins with a woman directly addressing the viewer, no longer surrounded by her lover, her friends, or her daughter. Weems’s grand finale, the last word of chapter and verse, is a woman playing solitaire. Having liberated herself from a bad relationship and the social constrictions of motherhood, her protagonist relaxes with a smoke, a glass of wine, and some chocolates—perhaps a valentine from a new suitor? Placed just before this picture, the closing text panel in the series announces, “Presently she was in her solitude.” Though her bird has literally and figuratively flown the coop, the woman seems unconcerned rather than lonely, defeated, or abandoned.

Kitchen Table Series, however, is not a story about simple justice served. The teller of this tale is neither saint nor sinner; the moral is not black or white but rich shades of gray. The measured photographic chronicle is countered by the raucous accompanying texts, which describe a far darker narrative echoing with a chorus of voices—those found in vernacular expressions, rhymes, and lyrics—coalescing into that of the imperfect heroine. The last text panel features lines from “Little Girl Blue,” a song immortalized by Ella Fitzgerald and Nina Simone, whose vocal shadings, we can imagine, provide a ghostly sound track for the woman playing solitaire, who is also a lady singing the blues about a man who done her wrong. She’s a little girl blue looking for a blue boy, who can only ever count on raindrops, who tells it like it is.

The woman is playing the game of solitaire, but is she also playacting as solitaire, a character like a jester, a harlequin, a domino? Just as the mute image is haunted by Nina Simone’s voice, its monochrome tonality calls for us to imagine the color of Weems’s costume, perhaps a shimmering gold blouse festooned with a regal purple trompe l’oeil jewel necklace. Is she a clairvoyant, a light seer (as well as a light writer/photographer), reading the cards to foretell her future? The text panel tells us finding a man will “have to come later.” This picture suggests she is in no hurry, she holds all the cards, she’s testing her luck before making her next move.

Jennifer Blessing is Senior Curator, Photography, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.