Mark Bradford, Pride of Place, 2009

Mark Bradford’s photographs, like his grid-based abstract paintings, are maps. They always seem to be charting the ways identity spreads across the different territories of the body. In Pride of Place (2009), a series of twenty chromogenic prints, Bradford becomes a cartographer of the body’s failure. The individual photographs show the limitations of the myth that the body is a neat container of race, sex, and gender performance.

Bradford, a very tall, black, gay man, was born in inner city Los Angeles in 1961. For Pride of Place, he transforms himself into an NBA star in drag, fashioning himself in a vintage Los Angeles Lakers jersey on top of a voluminous purple and gold dress. Against a warm, orange backdrop, he engages in a performance, playing up the physical expectations of height, weight, and appearance. In the foreground, the camera catches Bradford’s back as he rolls and falls. Arms failing, it seems as if he has lost his balance trying to be someone he’s not.

“Working within this landscape, for me, a 6’7” black male, is likened to Madonna (the singer, that is) being allowed to give a concert in Vatican City,” Bradford told Christopher Bedford in a catalogue interview for the 2010 exhibition Hard Targets at the Wexner Center for the Arts. “It’s just too good to pass up, and what is too good to pass up is the questioning of my maleness and the black body. So many times in America we think we know the black body, enough to understand and draw formal conclusions about it. I wanted to mix it up a little, to peek under the dress.”

Pride of Place was inspired by Bradford’s 2003 single-channel video performance Practice. For three minutes, Bradford’s moving image can be seen on a basketball court running, dribbling, and clumsily negotiating space and desire. At some point, he shoots—swoosh—nothing but net. The artist’s static and moving body in Pride of Place and Practice gesture toward what success looks like, even in failure.

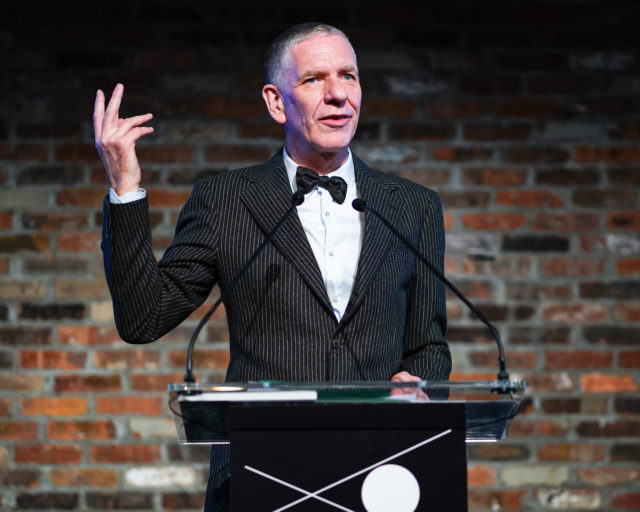

Mark Bradford will represent the United States at the Venice Biennale in 2017.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.