Vision & Justice Online: Renée Mussai in Conversation with Victor Peterson II

Coinciding with the release of Aperture’s summer issue, “Vision & Justice,” Renée Mussai, Curator and Head of Archive at Autograph ABP in London, discusses the politics of representation in photography from the African diaspora.

James Barnor, Eva, 1960. Courtesy Autograph ABP

Photography writes stories with light and, like sound, resonates within us. These stories are hieroglyphs to some, living word to the initiated. Etched on Shoreditch’s brick and pavement are stories from the anti-establishment dreams of the 1960s to the cultural movements of today. For almost three decades, Autograph ABP has told the stories of the black experience through photography.

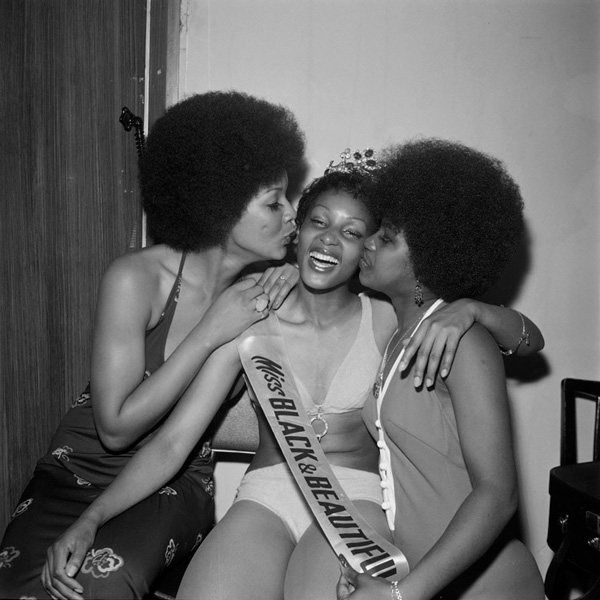

In 1988, Autograph ABP was established in London to advocate for the inclusion of black image-makers and black subjects in cultural institutions. Originally located in a Brixton office, its current location, as of 2007, sits at 1 Rivington Place in East London. The building’s matte grey façade, designed by David Adjaye, is nestled in scenery befitting that uneasy, yet coveted moniker of an “up and coming” neighborhood. Since moving to the East End, Autograph has presented numerous exhibitions including Black Chronicles II, Syd Shelton: Rock Against Racism, James Barnor: Ever Young, Maud Sulter: Syrcas, and Raphael Albert: Miss Black and Beautiful. Exhibitions also tour internationally; Black Chronicles has traveled to Spelman College Museum of Fine Art in Atlanta and The Hutchins Center’s Cooper Gallery at Harvard University, while James Barnor: Ever Young is currently on view at Theaster Gates’s Stony Island Art Bank in Chicago.

This spring, I spoke with the curator Renée Mussai at Autograph ABP about the thematic and historical resonance between Black British photography and the politics of representation in the African diaspora. Here, she discusses her research-led curatorial work focusing on archives, postcolonial portraiture, and the themes of race, gender, and sexuality in historic and contemporary photography. —Victor Peterson II

Renée Mussai, Curator, at the exhibition Black Chronicles II, 2014, Autograph ABP, Rivington Place, London. Photograph © Zoë Maxwell and courtesy Autograph ABP

Victor Peterson II: What first caught your interest in photography?

Renée Mussai: I was afraid you might ask me this! Growing up in Central Europe in the 1980s, as a product of an interracial union, with only one culture present and the other absent, my childhood was marked by an occasional longing for images that I could relate to personally, images that depict people who looked a little more like me. So from an early age onward, I have always been obsessed with images—the abundance of certain representations, and the invisibility of others. My sustained interest in the tradition of African studio photography, and long-term engagement with the work of photographers such as James Barnor, stems from a photograph taken in Mogadishu in the early 1980s. In that picture, my Somali relations, including my father and grandmother, pose against an elaborately painted backdrop. As a child, this photograph served as the only palpable link to “that” side of my cultural heritage: I was equally intrigued by the portrait’s artifice, and by the people in it, most of whom I had never met.

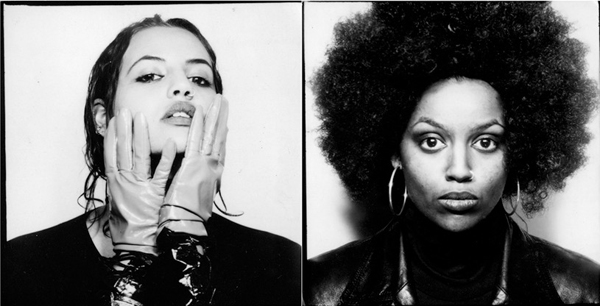

Renée Mussai, Madame Mulatresse, photo booth portraits, Migros supermarket, Switzerland, 1990s. Courtesy Renée Mussai

I grew up in the Austrian Alps with an extraordinary, wonderful single mother and a close-knit family. To encounter other Afro-Europeans, Africans, African Americans, or people from similarly mixed cultural backgrounds, was rare—in real life, or in pictures. Think of James Baldwin’s “Stranger in the Village,” a brilliant essay on his experience of living in a small Swiss village during the early 1950s. Picture that and then conjure an image of The Sound of Music . . . And so, in my early teens, I began a strange ritual of taking the train across the Swiss border to visit a particular shopping mall that housed a very special photo booth: one of those vintage machines that produces a strip of four different exposures resembling medium format square portraits. If I was feeling especially adventurous, I’d take a bag of props with me: a wig, make-up kit, accessories, et cetera. And, once inside, I’d try out different shades, different personae: from a pale-skinned Monroe-esque movie starlet fantasy, when I was twelve, to a revolutionary Angela Davis civil rights avatar, in my formative years, just before I left Austria for London. It was inside this miniscule enclave of a public-private hub that I fell in love with photography, while I was processing—literally—a range of existential moments. Photography offered a prism through which I could playfully engage with my own cultural identity, or identities, and explore different modes of being and becoming. A little narcissistic, most definitely, but necessary, too. Sometimes I’d invite lovers, friends, and family to join me in these portraits. And as an undergraduate photography student, in the early 2000s, I created my first art installation based on this archive of hundreds of images.

On a less self-indulgent note, the first time I used a camera myself was during an obligatory class visit to Mauthausen, one of Hitler’s main concentration camps in Upper Austria. I must have been about eleven or twelve years old, perhaps younger. Systematically photographing each room and each encounter was the only way I could comprehend and process the sense of haunting the place incited in me, the ontology of horror that was deeply imprinted everywhere, embedded in its walls, in the very aura of the place.

So I suppose the sum of these three experiences or impressions brought me closer to understanding and appreciating the remedial and political work images can perform—politically, culturally, personally.

Peterson: The title for Aperture’s summer issue is “Vision & Justice.” What does this mean to you? How is one implicated in the other, if at all?

Mussai: And a very intriguing title it is. One of the first things that comes to mind is the relationship between photography and human rights—inherent in Autograph ABP’s mission—and how photography can be deployed as a tool for resistance or oppression. Vision is also, of course, intrinsically linked to the act of seeing, a kind of apocalyptic or visionary seeing, if you will: seeing with determination, imagination, and wisdom; seeing for a cause, with conviction.

Young African American woman, three-quarter length portrait, facing slightly right, with hands folded on her lap, from African American Photographs Assembled for 1900 Paris Exposition. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Historically, I think of W.E.B. Du Bois’s “American Negro” installation, presented at the 1900 Paris Exposition, one of the most significant photographic interventions. Du Bois was effectively the first black curator of photography. His project was driven by an undeniable humanist concern and an undying belief in the visual as an effective political tool to institute social change. Together with others who shared his mission, Du Bois strategically deployed 363 photographs to stage a claim for the humanity of the black subject. And, in that moment, he was perhaps also the first scholar-activist who turned to photography as a campaign tool presenting visual “evidence” en masse. At Autograph, we presented a contemporary installation of 200 of these photographs under the title The Paris Albums 1900, which toured to the W.E.B. Du Bois Research Institute at Harvard (now the Hutchins Center) in 2013, marking the fiftieth anniversary of DuBois’s passing.

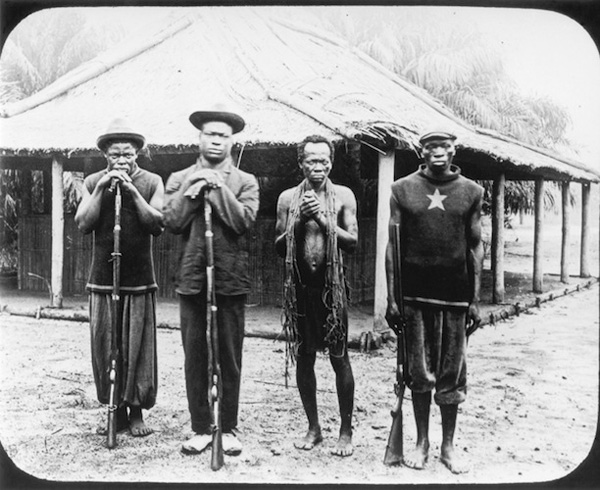

I also think of When Harmony Went To Hell: Congo Dialogues, another recent Autograph project championed by Mark Sealy, which highlighted the human rights campaign in the Congo, where photography—through the lens of English missionary Alice Seeley Harris, a figure rarely mentioned in the history books—played a pivotal role in securing justice to end the genocide inflicted upon the Congolese people by the violent regime of King Leopold II of Belgium.

Alice Seely Harris, Three head sentries of the ABIR with a prisoner, Congo Free State, ca. 1904. Courtesy Anti-Slavery International and Autograph ABP

The concept of social justice as married to photography and cultural identity politics has been deeply embedded in our human rights agenda since the early 2000s, when Autograph first began to engage with artists such as Marcelo Brodsky, whose work deals with state terrorism throughout Argentina’s “Dirty War.” Implicit in this mission is a continuous investigation of questions around access, equality, and responsibility, and how these relate to the visual and privileged spaces of museums, galleries, and the academy. Mark Sealy, Autograph’s director since 1991, has spoken and written vigorously about the relationship between cultural violence and visual politics over the years. Under his vision, the organization has become an agency and gallery uniquely placed in incorporating human rights as an extension of race and representation in relation to photography, and increasingly also moving image works.

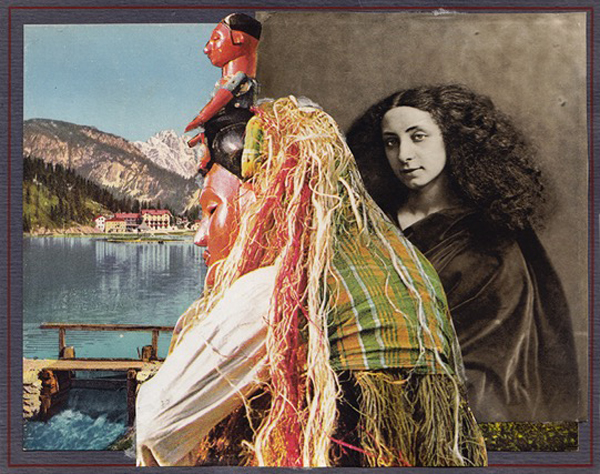

Maud Sulter, Duval et Dumas, 1993. Courtesy of Maud Sulter Estate and Autograph ABP

Peterson: What do you see as Autograph’s responsibility to and for representations of the black diaspora? For generations, people from all over the world have been settling in London, often coming from the UK’s former colonies. I’m thinking, historically, of the HMT Empire Windrush voyage from Jamaica to England in 1948—what many would say was a starting point for talking about the emergence of a black British culture in London.

Mussai: The “burden of responsibility”—where does one begin? It is important to remember that Autograph was born out of the black arts movement of the 1980s, a time of extreme Thatcherite conservative politics, serious oppression, marginalization, and discrimination. But this era was also a deeply creative time, when a pioneering generation of black artists entered art schools and infiltrated mainstream establishments; they also formed influential artist collectives and independent platforms to nurture their practices. Identity politics, for lack of a better term, played out across several, convergent lines of sexual, cultural, and racial differences, and many concurrent dialogues emerged out of this moment. There, are of course, many ways to look at the question of responsibility. One key aspect of our continuous curatorial responsibility lies in preserving the legacy of certain influential artists, such as the work of Rotimi Fani-Kayode (1955-1989), a founding member and the first chair of Autograph ABP, or that of Maud Sulter (1960–2008), a pioneering curator, writer, and artist whose work we recently presented at Rivington Place, and at this year’s Rencontres d’Arles in France. Without sustained advocacy, these artists are invisible, their contributions erased, forgotten, which is, ironically, a prevalent theme in their work. Part of our mission is to inspire other institutions take notice, and consider these and other artists’ work in their collecting and exhibiting frameworks.

In addition to operating within contemporary and postcolonial creative spaces, we are increasingly turning our attention to mining image archives, contributing new knowledge to the ongoing writing and re-writing of photographic histories. While our work is often directed at filling gaps of a particular focus, the aim is to annotate and affect wider cultural narratives, and address what we refer to as a series of “missing chapters” above and beyond specific black or diasporic histories.

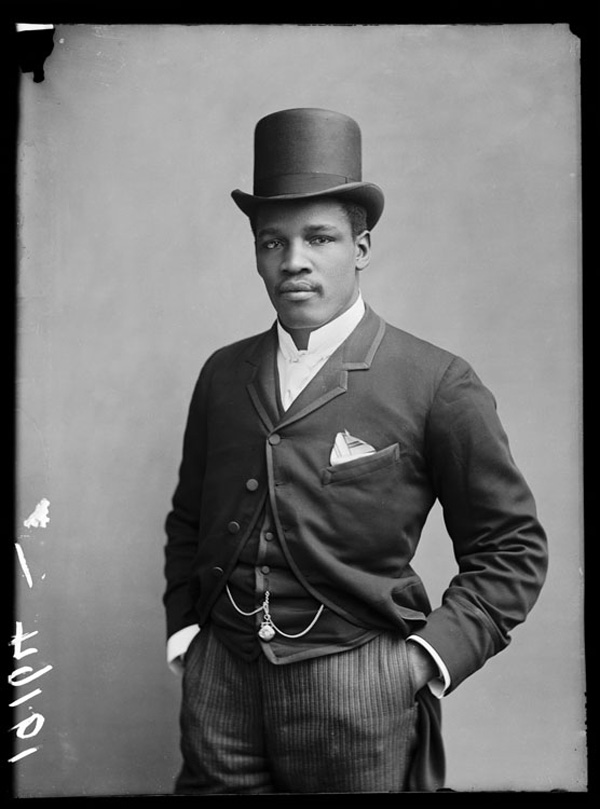

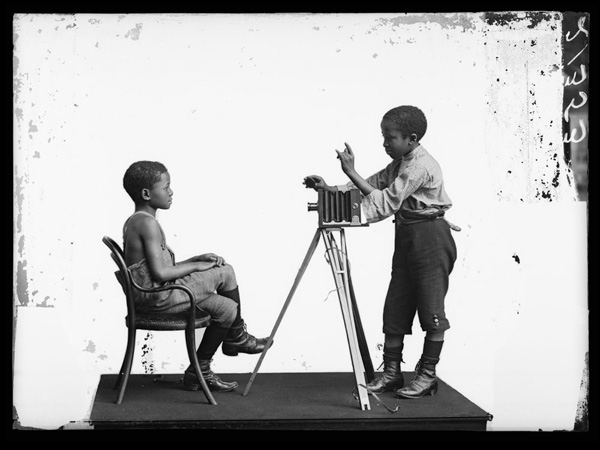

Peter Jackson, London Stereoscopic Company, 1889 © Hulton Archive/Getty Images

It’s interesting to me that you frame your question in the context of the Empire Windrush, as much of our recent curatorial work has been about quietly unsettling or dislodging this so-called watershed moment in 1948, too often erroneously cited as the beginning of a multicultural Britain. Oftentimes, our archive research arises out of the desire to disrupt established narratives of “arrival,” to unlock the coming of diaspora from a post-war moment. The black diaspora in Britain—and in the rest of Europe—is so much older than generally assumed: it dates back hundreds of years, all the way to the Roman Empire. For many years, Caroline Bressey, for instance, has been researching these so-called “hidden” histories of black presence in Victorian and Edwardian Britain in great depth, considering black women and their stories in particular. We know of different “presences” from art history, illuminated by great scholarly publications such as the multivolume series The Image of the Black in Western Art (recently re-published by Harvard University under the editorship of David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates, Jr.). But paintings and drawings are often produced from the artists’ imagination, while photography in the nineteenth century was primarily seen as “evidential,” one of the reasons I believe why Black Chronicles II, our touring exhibition on black portraitures in the nineteenth and early twentieth century Britain, has resonated with audiences and critics alike. Many of the photographs in the exhibition were shown for the first time in more than 135 years, extracted from the Hulton Archive in London, one of the world’s oldest and largest image archives. Through this strategic partnership, made possible through our Heritage Lottery-funded Missing Chapter program, we were able to collectively affect the way the black figure is represented in nineteenth-century photography in Britain.

Returning to your question: to offer new knowledge about the representations of the diaspora, to ensure diverse voices are not only heard but acknowledged and incorporated in larger narratives, to preserve the legacy of those artists who have shaped this path, and to provide a platform for those working today in the charged arena of cultural politics and the visual, is where I see our critical responsibility as curatorial agents.

Peterson: In your work as a curator and scholar, do you think of yourself as telling a story with images or do the images tell their own story?

Mussai: Roland Barthes, I believe, once famously described the photographic image as “a message without a code.” Personally, I’ve always been more intrigued by the idea of deciphering a photograph’s “stored code.” I suppose I think of myself as a translator, or as a kind of mediator, an organizer, of images. That is not to say that images aren’t capable of telling a story on their own. I believe in photographs having a “voice,” albeit one that constantly shifts and mutates upon reception, and often the images themselves benefit from “interpretation,” mediation, advocacy.

Black Chronicles II, installation view, Autograph ABP, Rivington Place, London 2014. Photograph © Zoë Maxwell and courtesy Autograph ABP

I’m interested in new image configurations and their concomitant reverberations that emerge through archival acts of resurrection, and at times bricolage. A lot of our work is driven by this Foucauldian notion of “excavation” and the creation of new narratives, new meanings, through the re-assembly of images and texts, which at one time or another, were “orphaned.” These stories change over time. The curatorial work needed is to provide a cohesive framework to channel their collective registers—their “voices.” The juxtaposition of text and image in Black Chronicles II is a good example, where a series of citations by the late Professor Stuart Hall on the gallery walls subtly animated the archival work on display.

Peterson: How do we write ourselves into history or make our own narratives through images? What takes precedence, fitting into a narrative or creating one’s own?

Mussai: Often, the desire to write new narratives is driven by a perceived sense of lack, because we feel that we don’t fit into existing accounts. The desire to tell your own story, to find one’s place within history or the contemporary, within the archive and its image repertoire, is a natural drive towards the validation of one’s existence, especially for artists working in a space defined or somehow marked by “diaspora,” and affected by themes of displacement, whatever these may be. I believe we resurrect images from the archive to say something about our times, usually informed by a desire or need for them in the present.

Perhaps the key is to see history, or the archive, not as a prison-house of the past—to paraphrase Stuart Hall—but as a space of contemporary relevance, and to reflect carefully about our reasons behind these “resurrections.” Then there are “acts of inscription,” a term I used recently in a transatlantic project in collaboration with my friend and colleague Ruti Talmor. I believe that some of the most profound artworks are born out of this moment when subjectivity meets history, and in the act of inserting oneself into a grand narrative of absence. See Yinka Shonibare’s Effnik for instance—a seminal piece of work Autograph APB commissioned in 1996, and which we recently showcased as part of Black Chronicles II.

Yinka Shonibare, Effnik, 1996. Commissioned by Autograph ABP. Courtesy Autograph ABP

When fitting images into a narrative of the past is not possible, then the creation of a new archive becomes the only viable option, a necessary act. Take Zanele Muholi, for example, one of the most courageous artists of our time, for whom photography is never a luxury, but a necessity. And through this necessity she has created a singular, living photographic archive of African queer, black, lesbian, and non-gender-conforming individuals, with the mission to contribute toward a more democratic and representative national history of post-apartheid South Africa. That visual story did not exist before. It was her art and activism that created it, conjured its space in history, and created both agency and visibility for a community that is perpetually marginalized, and threatened by xenophobic and homophobic violence. Work such as hers forces us to reconsider how histories are written, and to take action in writing our own stories.

Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Cargo of the Middle Passage, 1989. Courtesy Autograph ABP

Peterson: How does Autograph figure into an historical narrative of a black radical presence and national identity?

Mussai: Autograph ABP was founded by a constituency of radical young artists, curators, and activists from African, Caribbean, and Asian backgrounds in late-1980s London. All of them were creative practitioners in their own right, whose work was driven by the desire to “tell their own stories” as diasporic and displaced subjects. At the time, their work was rarely recognized as significant, or seen as relevant, and was largely ignored by mainstream institutions. Yet the founders were deeply instrumental in shaping an emerging black arts movement, whose waves are still palpable today. A perfect example is found in Rotimi Fani-Kayode. Amongst his contemporaries, he was without precedent. His repertoire of tropes and signifiers was too multi-layered to define: black, African, queer, bohemian, political, erotic, spiritual. To claim a hostile space as your own, to write your own narrative in troubling times is always a radical and deeply transgressive gesture. And since the organization’s formation nearly thirty years ago, Autograph ABP has actively engaged in a space of radical visual cultural politics through progressive curatorial work, scholarly discourse, new commissions and publications, education and outreach, and through mining different image archives.

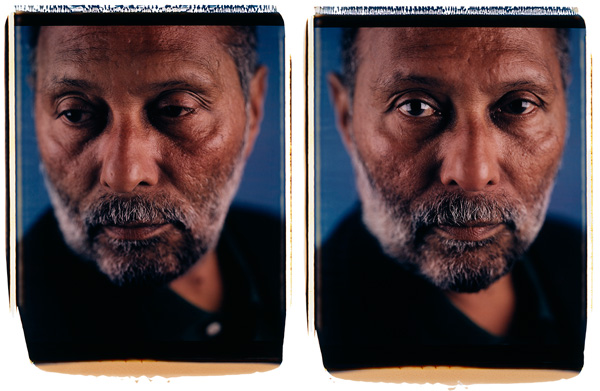

Dawoud Bey, Stuart Hall, London, 1998. Courtesy Autograph ABP

Peterson: What is the legacy of the Association of Black Photographers and, in particular, the work of Stuart Hall and cultural studies at Autograph ABP?

Mussai: To answer this question, allow me tell you an anecdote. A few years ago, I went to visit Stuart Hall at his home in Hampstead. It was a Sunday afternoon just before Christmas. We had tea and spoke about my PhD, on which I was about to embark, and I was seeking his advice. As we left, my son, who was about seven years old at the time, said to me, “Mum, this old man is very good with words, isn’t he? I could have listened to him much, much longer.” I’ll never forget that moment, because it was so profoundly moving, funny, and to the point: I’ve never known a person in my lifetime as succinct and eloquent as Stuart Hall. He was influential in so many different fields, and he was also one of the first scholars in Britain to write about photography in relation to cultural difference, race, and representation.

So, Stuart Hall’s critical thinking has been a tremendous source of inspiration and support over the past decades, it and still is. In fact, Autograph was launched in 1988, in his presence, at The Photographers’ Gallery. In those days, the organization was known as the Association of Black Photographers in London. Today the acronym “ABP” points to this legacy, but we no longer refer to ourselves as an “association of black photographers,” and our remit has broadened considerably since. As our chairman for more than seventeen years, from 1991 up until his retirement in 2008, Stuart’s generosity of spirit was fundamental to the 2007 establishment of our home and gallery base in Rivington Place, for which he championed with unparalleled dedication. The continuous impact of his thought is evident in recent installations such as Black Chronicles II, which is dedicated to his memory. His legacy is also preserved by projects such as The Unfinished Conversation, a critically acclaimed three-screen film work by John Akomfrah, commissioned by Autograph in 2013.

Professor Stuart Hall, James Barnor, and Renée Mussai at the opening of James Barnor: Ever Young, Autograph ABP, Rivington Place, London 2010. Photograph © Zoë Maxwell and courtesy Autograph ABP

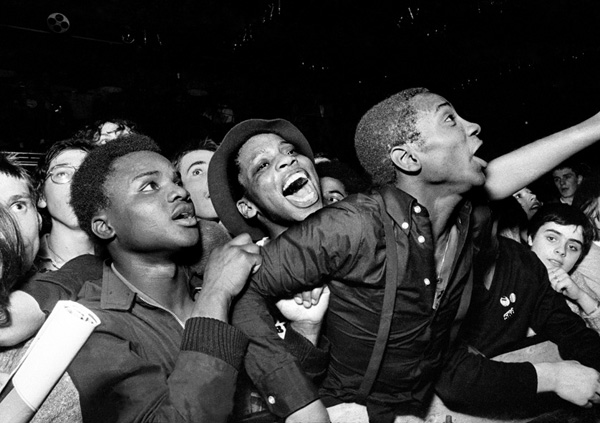

Peterson: How does the recent exhibition Rock Against Racism relate to movements today such as Afro punk or Black Lives Matter?

Mussai: Syd Shelton’s Rock Against Racism (RAR), an exhibition and a book, is one of our most successful recent projects, brilliantly curated by Mark Sealy in collaboration with Carol Tulloch. The project was so successful partly because people could relate to the visual testimony on a personal level, and due to its contemporary relevance. For many people, RAR is a living memory. For others, the collective coming-together of people from all kinds of different cultural and social backgrounds to fight the rise of neo-fascism and racism has a profound resonance in the present.

Syd Shelton, Special fans, Potternewton Park, Leeds, from Rock Against Racism, 1981. Courtesy Autograph ABP

On view concurrently with RAR was a small showcase I curated in the upstairs gallery at Rivington Place, a series of photographs by Bruno Boudjelal that we commissioned a few years ago to mark fifty years of Algerian independence. The exhibition juxtaposed Bruno’s photographs with excerpts from writings by Frantz Fanon, which are displayed on the wall, in vinyl. One of the citations, from The Wretched of The Earth, reads, “When we revolt it’s not for a particular culture. We revolt simply because, for many reasons, we can no longer breathe.” It only occurred to me retrospectively how very poignant—and potent—these words are when read in relation to the Black Lives Matter campaign, and other current, transatlantic movements.

Rock Against Racism, installation view, Autograph ABP, Rivington Place, London 2015. Photograph © Zoë Maxwell and courtesy Autograph ABP

Peterson: This question is something that I have been thinking about for a while. When I was younger, a nickname of mine was “black magic.” It has had a profound effect on how I see the world. Do you believe in magic?

Mussai: Yes. I am intrigued by everything remotely supernatural. And as a teenager, I used to think of photographs as magical, transfigured objects. Back then, the darkroom represented this intoxicating and deeply magical space for me, a complete realm of enchantment: the red light, the chemicals, the textures and movement of the liquid in the tray, the uncanny process of giving birth to an image, its transition from the sphere of nothingness into visibility. Photography is rooted in science, of course, but how can that not be utterly magical also? Hannah Arendt has described art as a process of magic, and she located that magic in the artist’s transfiguration of something ordinary into something extraordinary, an expression of the infinite in the finite world of things. I also believe in amorous magic, the Nina Simone “I Put a Spell on You” kind of magic . . . but that’s another story. Apropos names: I never had a nickname, but Renée means “re-born” in French and Melanie, my middle name, derives from the Greek melania, as in dark, or blackness. And I’ve always quietly enjoyed the notion of being called something akin to “the dark one reborn!”

Renée Mussai, 2016. Photograph ©Maliq Mitchell and courtesy of Autograph ABP

Peterson: Growing up in the U.S., everyone had a nickname. “Magic,” for me, has to do with movement and imagination. Everything in the world, everything that can be, is already here, just moving at different speeds in relation to each other. The world, then, can be seen as a theater of images. Some of us can see things coming from outside of the frame before others. The first seers of these images are called magicians. Maybe they just see more of the world, and from a different point of view. In a way, photographers do this all the time.

Mussai: What a wonderful proposition, and so very visual . . . Makes me recall the work of the science fiction horror writer H.P. Lovecraft, and his parallel visual spheres. In the his universe, the creative process is always associated with dreams. Images born in and of dreams are tied to the “delirium” of creation. Magic and its connection to a historical trajectory of reinforcing cultural legitimacy—vampires and witches in popular culture, for instance—hold a particular affinity for me, something about difference and visibility, I presume. Mythical vampires only exist in a transitory realm of the visual: they resist even their own reflection, yet they are forever moving through changing visual stimuli and altered temporalities—through what you so beautifully describe as a “theater of images.”

Peterson: If the world is made of images, how do you see yourself and Autograph with regard to curating images from the past and present, was well as proposing future images for others to look at and read themselves into?

Mussai: Well, I think the first thing we must remember is that we read images from the position of the present and thus these “imaginings” are never stable, or moored within fixed temporalities. And, as such, they require delicate and considerate excavation, when working with contemporary practitioners, or within the archive. What is at stake? Who are we speaking to, and why? Why now? The objective is to create conditions in the present that make it possible for such critical visual dialogues to be fostered between the past and the present, for multiple historical trajectories to be acknowledged, explored, and to create spaces that enable transformative encounters and offer new knowledge.

Raphael Albert, Miss Black & Beautiful Sybil McLean with fellow contestants, Hammersmith Palais, London, 1972. Courtesy Autograph ABP.

Peterson: What photographers are you excited about at the moment?

Mussai: I am always interested in socially-engaged work that addresses the politics of gender, sexuality, or the post-colonial condition: for instance, the work produced by artists such Zanele Muholi or Sammy Baloji, whose new book Suturing The City: Living Together in Congo’s Urban Worlds, we just published. Currently, I am excited by the work of emerging contemporary artist Aida Silvestri, who deploys innovative and hard-hitting visual strategies to address potent topics such as female genital mutilation or human trafficking. Her solo show Unsterile Clinic is on view at Autograph ABP this summer.

Aida Silvestri: Unsterile Clinic, installation view, Autograph ABP, Rivington Place, London 2016. Photograph © Zoë Maxwell and courtesy Autograph ABP

And I am always open and receptive to what the archive has to offer. At the moment, this means a schizophrenic oscillation between several projects. The basis of our next exhibition, the uncatalogued image archive of the late Raphael Albert, features a vast array of photographs of women in swimsuits posing for black beauty pageants in 1970s London. And then, of course, the ongoing research of Victorian portraiture of black figures in nineteenth-century Britain, as part of the Black Chronicles series, which is the subject a book to be published by Autograph ABP in partnership with Harvard University’s Hutchins Center this fall, as well as our ongoing Missing Chapter archive program, and my associated PhD research. I am excited by work that rebukes any notions of certainties, that operates outside of established regimes of truth, and, instead, opens up new configurations, new ways of seeing.

Albert Jonas and John Xiniwe, London Stereoscopic Company, 1891 © Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Renée Mussai is Curator and Head of Archive at Autograph ABP, and a PhD candidate in Art History at University College London. Victor Peterson II, a writer from Philadelphia and former editorial assistant at Aperture magazine, is currently conducting research in black cultural studies at Kings College, London.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.