Vision & Justice Online: Sheila Pree Bright in Conversation with Naima J. Keith

A photographer connects leaders of the civil rights movement to the young activists working today.

Sheila Pree Bright, Atlanta, from the series #1960Now, 2015

The photographer Sheila Pree Bright, a Georgia native who is currently based in Atlanta, has routinely questioned the power structures that inform representations of African American communities and individuals. In her latest series, #1960Now, Bright connects leaders of the civil rights movement to the young activists working today. In chronicling street demonstrations in Atlanta and Baltimore, she summons the dramatic energy of Leonard Freed’s high-contrast documentary photography, while her minimalist portraits of activists recall the intensity of Richard Avedon’s work from the 1960s. Bright presented an interactive version of #1960Now at The Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia in fall 2015, but she has also moved her photography beyond the gallery walls through wheat pasting campaigns and Instagram hashtags. At a moment when social justice, inequality, and representation are national concerns at the highest levels of politics and media, Bright’s photography provides a potent mediation on the ongoing work toward racial progress in America.

Naima J. Keith: You’ve been described as a cultural anthropologist, yet your work explores commercialism. Is this an accurate title? Would you describe yourself the same way?

Sheila Pree Bright: Considering my work, I understand why I’ve been described that way. However, I define myself as a fine art photographer. The visual content I capture challenges ideas about narratives that are controlled by Western thought and power structures. My approach is to seek the common thread that connects the human condition. I aim to examine what people define for themselves.

In my work, I explore the ways in which black bodies have been considered a commodity. I study the collective black experience against other histories to communicate the humanity in us all, with the intent to break taboos and stereotypes—but mostly to celebrate the beauty that lives beneath the surface of those presented as inferior, powerless, or misunderstood.

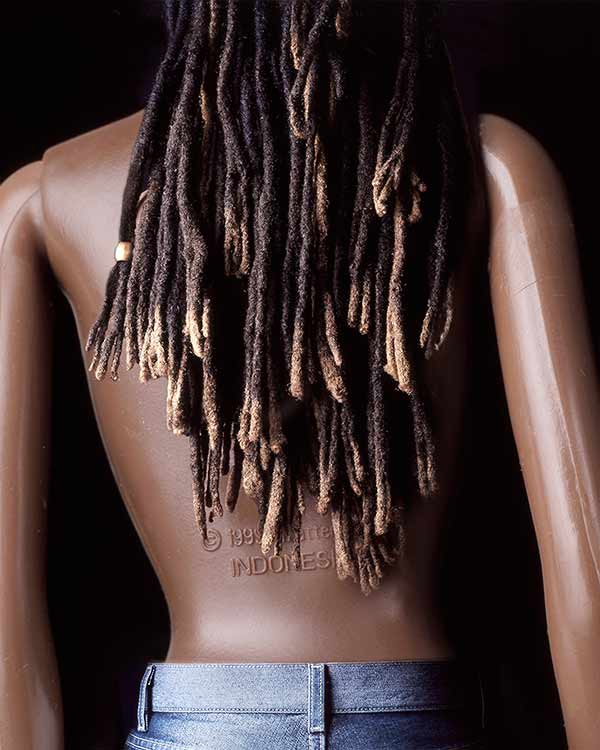

Keith: One of the ways you’ve investigated the black body is in the series Plastic Bodies, in which you take the famed Barbie doll, a toy prized among young children for decades, and explore the relationship African American women have with this Eurocentric standard of beauty. How do you view the relationship between women and Barbie dolls?

Bright: There is an infatuation about physical beauty among both men and women. Plastic Bodies (2003) explores deconstruction and reconstruction of beauty. I digitally manipulate photographs of women and dolls to address the thin line between fantasy and reality via PhotoShop. I use the Barbie as the “ideal” of beauty and examine her as a cultural icon. My interest is in how black bodies are seen as undesirable by Western standards. In my research, I closely studied the South African figure Saartjie Baartman, who became a spectacle of fascination when she was taken to Europe and publically displayed with attention on her large buttocks.

In 2016, Mattel launched a new line of dolls that are designed to be more “real.” On the front cover of the February issue of Time magazine, there is a Barbie with blue eyes and blonde hair that has a figure more like Kim Kardashian’s. African American female bodies are not frequently celebrated in Western culture, which is why, historically, platforms like Jet magazine’s “Beauty of the Week” have been important. As new counterculture blogs emerge, like AfroPunk, beauty is defined by cultural aesthetic, as seen in how their “Afro of the Day” series is reclaiming ideas of mainstream beauty trends.

Although Barbie serves as a toy for children, she represents much more. The doll somehow becomes a model of beauty, a false representation of how women are physically formed. In some cases, women will aspire to this model to the extent of deconstructing their own image by various forms of beautification. I show how these extremes are illusions by using models and dolls as the subjects.

Keith: What role does audience engagement play in your work?

Bright: Living in a world where millions of images are uploaded and consumed daily, it’s important for my work to live in different spaces in order to engage different audiences. Until 2012, my work only lived in museums and galleries. Young Americans (2008), a series of self-constructed photographic portraits of Generation Y, ages eighteen to twenty-five, shows attitudes and values of Generation Y as American citizens. Participants posed with the American flag, using it as a prop to express sentiments about America. The series premiered as a solo exhibition at the High Museum of Art. Then the series was taken to the streets of Atlanta and Art Basel Miami 2012 to reach people beyond museums. The work in a new space was a successful initiative in giving the residents of an urban neighborhood art they could own and relate to and in creating fresh dialogues about what it means to be an American in the twenty-first century. After the George Zimmerman verdict, having the work displayed in Florida was important and timely, as many Americans felt let down by the system.

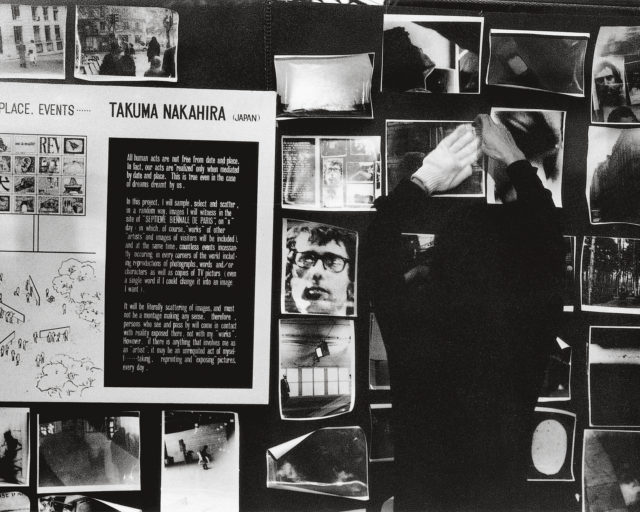

Recently, social media platforms have become a big part of my audience engagement. From the inspiration of street art, I produced 1960Who (2013), photographic portraits of unknown members of the civil rights movement. The series was presented in urban spaces as a street gallery and was also re-enforced on social media platforms. For example, my Instagram account, @shepreebright, went from 800 to 60,000 followers in 2015 through curating and campaigns such as the hashtag #BringIt1960Now for #1960Now series. Simultaneously, I was working on the project in real time before the opening at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia.

Keith: I’m intrigued by a series like #1960Now because, like you said, it engages both an online and a museum-going audience.

Bright: #1960Now explores the state and condition of America now. Themes in the series explore what “disruption” looks like. There are protests against injustice across the country, and around the world, and also there has been an emergence of fresh new leadership that is becoming more visible from the ground up. I’m exploring power struggles and how America is shifting socially, politically, and economically. The work I produced in the ’90s—the era of hip-hop culture—seems to relate to themes of past and present. I’m revisiting this work with the intention of reframing former series such as Suburbia (2006), and to create multimedia work that examines ongoing narratives of gentrification and how culture exists in different spaces.

Keith: Has being based in the South inspired you to move work like #1960Now in a particular direction?

Bright: The region has definitely influenced my work. Atlanta, where I am based, is the home of the civil rights movement. It is the foundation for my research, and where I met the primary founder of the Atlanta Student Movement, Mr. Lonnie King, Jr. I learned a lot about that era that isn’t in history books when I placed the 1960Who street art series on walls where youth leaders of the ’60s once held meetings and traveled throughout the city. The South is a very interesting place. Being born in the South, but not being raised in the South, and then returning to the South as an adult has piqued my curiosity about how current and past histories intersect.

Keith: What role does black and white photography (as used in #1960Now) play in your work that color photography does not? Was the choice for these works to be in black and white methodical or intentional?

Bright: Intentionally, the photos are black and white to represent a timeless history. #1960Now is a documentation of current events reminiscent of ’60s reportage in capturing the truth in struggles with police brutality and mass incarceration of black men. The aesthetic reinforces a critical thought about how different things really are today, compared to fifty years ago. To present the photographs in color would not honor the generations of people who took a stand. This is an important element of the work: I incorporate youth leaders both of current times and of the civil rights era who were not widely known. I hope the work will spark the audience to think critically, beyond what they see on the news, and to inspire dialogues between people of different races, genders, and generations.

Keith: Where do you draw inspiration for your work? What inspires you?

Bright: I am an observer. I’m inspired by observing spaces, people, and culture. Growing up, I was shy and introverted. I preferred to experience the world by engaging books. I hid under the bed a lot and read books from back to front. I wanted the conclusion first. Taking photographs became the way I communicated best. Images don’t require a lot of words.

My work is about controlling the narrative and finding new ways to broaden audience globally in different spaces. Art is a way to learn from others.

Read more from “Vision & Justice” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.