What “Greater New York” Got Right about Photography in the Age of Instagram

David Benjamin Sherry, Manorathadayakas, from the series Birth In Futureverse, 2008

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger loved whiskey and bourbon, so when the two young, Stanford-educated developers started a photo-sharing app, they dropped a couple vowels and called it Burbn. In the spring of 2010, with location-based services like Foursquare competing for venture capital, Burbn raised $500,000 in seed funding. Users could check in at a bar and post a photo, or just post a photo on its own. “I was excited about being able to help people tell their stories when they’re out and about,” Krieger later recalled in an interview with CBS This Morning. “Not when they’re at their computers at home, you know, downloading one hundred photos from their last weekend, but that instant right then and there.”

The first photograph Krieger uploaded to the app, which he and Systrom renamed Instagram, was an off-kilter view of San Francisco’s South Beach Harbor. Systrom posted a picture of soup, a taco stand, a puppy, and a cocktail. On October 6, 2010, Instagram arrived in Apple’s app store, and before the end of the year, one million users had joined the platform. Less than two years later, in April 2012, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg bought Instagram for $1 billion in cash and stock. The rest isn’t history, it’s the present. It’s the obsession of the art world. It’s the flotsam of celebrities and brunch. It’s the filters, the FOMO. It’s pics or it didn’t happen.

But what happens to art photography when everyone is a photographer?

© the artist and courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

That was the question in the spring of 2010, when MoMA PS1 opened its third iteration of the quinquennial exhibition series Greater New York, a survey of work by sixty-eight artists in New York’s metropolitan area, many of them photographers who have since earned remarkable prominence in the art world, journalism, and visual culture. Begun in 2000 to mark the merger of PS1 and the Museum of Modern Art, the 2010 edition of Greater New York arrived at an inflection point in photography, in the year that Instagram was founded and Apple introduced the iPhone 4 (with its rear-facing, selfie-enabling camera), but also at a moment when museums and art institutions were breaking down the parochial borders between medium-specific departments, and when artists were rapidly exploding traditional disciplines by using pictures as just another tool at hand.

The exhibition, as MoMA Director Glenn Lowry wrote in the foreword to its accompanying catalogue, was meant to give audiences a “proleptic sense of the promises of the future.” Ten years later, the inclusion of artists such as Hank Willis Thomas, Deana Lawson, David Benjamin Sherry, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Michele Abeles, K8 Hardy, Daniel Gordon, and Xaviera Simmons appears prescient. When it came to anticipating the future of photography, how did Greater New York get so much right?

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

Connie Butler, one of the curators of Greater New York, remembered having conversations with artists and curators at the time about how photography was changing, how new technologies were influencing the circulation of images. “There was a growing feeling of a crisis in photography because of it,” Butler, who is now the chief curator at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, told me recently. “At the time it was like, Oh my god, how are we going to sort this out? Everyone’s taking pictures.”

Butler and her cocurators—Klaus Biesenbach, the former director of MoMA PS1 (and current director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles), and independent curator Neville Wakefield—put out a broad call for artists through submissions on the MoMA PS1 website, inviting artists for presentations, and making numerous studio visits in the New York area. “It was an attempt at a kind of democratizing structure, where we could cast the widest net, so I think that’s also reflected in the range of photography we got,” Butler said.

Butler recalled that the curators sat in a room at PS1 with hundreds of Post-its and papers on the wall as they shaped the exhibition, bringing together artists working in video, sculpture, painting, performance, and photography—and others who produced genre-defying installations. Butler noted the vast difference in approach among the photographers and lens-based artists, some of whom were looking reflexively to the medium’s history. Mariah Robertson, for example, contributed one-of-a-kind, abstract compositions on metallic paper, experimenting with kaleidoscopic shapes and layers, and employing analog processes “that have been marginalized in the wake of digital photography,” as the curators write in the catalogue. David Benjamin Sherry similarly drew on old-fashioned practices in his color-drenched landscapes, made in the darkroom even though they could have been more easily achieved in Photoshop. “Sherry’s refusal to concede to the convenience of technological innovation,” the curators noted, “points to a nostalgic desire to preserve the painstaking, laborious processes of the past.”

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

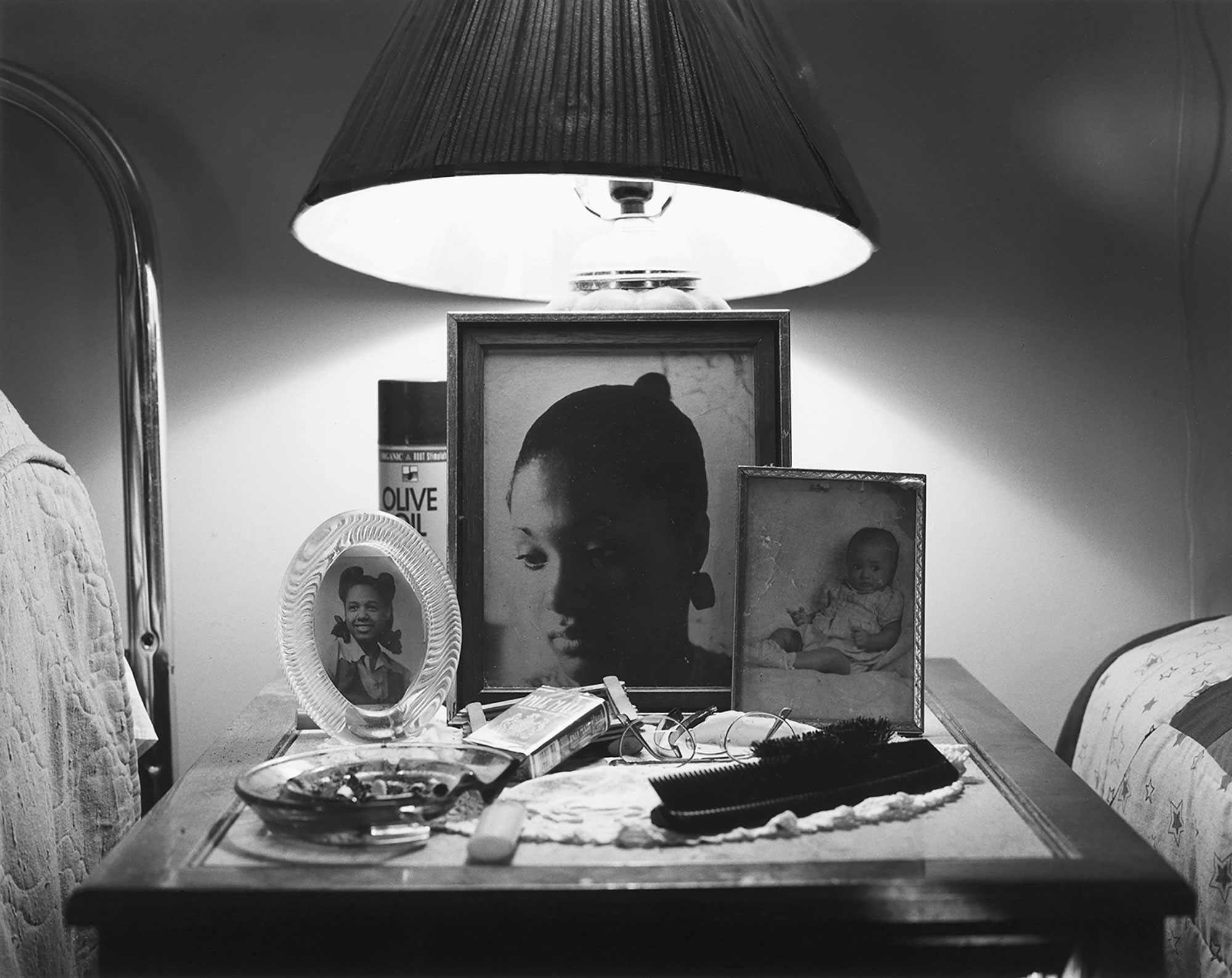

Among the most resonant contributions to Greater New York were works by Hank Willis Thomas, Deana Lawson, and LaToya Ruby Frazier, whose diverse approaches are united, Butler said, by “images of Black life and Black bodies and Black domestic life.” Several years before Greater New York, Thomas began exploring “commodity culture” in the United States and the impact of advertising on perceptions of Black identity. In Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America (2006–ongoing), he removes the slogans from popular magazine ads featuring Black subjects, allowing images of Black and white figures to float untethered to brand associations as a way of interrogating stereotypes.

Lawson, known for her monumental portraiture, created a site-specific installation of found photographs, Assemblage (2010), composed of four-by-six-inch Walgreens prints of images found in archives or pulled from personal collections, a “biological mass” that she called a “visual regeneration of human histories and futures.” Assemblage staged a dramatic, tactile encounter, and asserted, like many other works, “the potential physicality of photography,” as Biesenbach noted in his introduction to the exhibition. (Lawson was recently awarded the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s 2020 Hugo Boss Prize.)

Courtesy MoMA PS1

Frazier presented works from her series The Notion of Family (2001–14), an epic, profoundly personal photographic essay about her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania, and the impact of gentrification and environmental degradation on the lives of her grandmother, her mother, and herself. (Aperture published this project as a book in 2015.) Frazier, who won a MacArthur Fellowship in 2015, and who now teaches at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, has since covered the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, for Elle; and the closure of a GM plant in Lordstown, Ohio, for the New York Times Magazine.

Thomas and Frazier both have active social practices, and political advocacy is “an extension of their work,” Butler noted. Thomas cofounded For Freedoms, an organization advocating for direct action by artists in political discourse. Frazier transformed her trenchant photojournalism into gallery and museum exhibitions, including The Last Cruze, organized in 2019 by the Renaissance Society in Chicago, which centered the voices and lives of people affected by economic decline in the Midwest.

© the artist

“They are really thinking about how their work lives in the world,” said Eva Respini, the chief curator of the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston (ICA), referring to Thomas, Frazier, and Lawson, as well as to Xaviera Simmons and A. L. Steiner—whose work is rooted in the queer community, and who was also featured in Greater New York. “They continue to stay true to who their communities are, what their worldview is, and an insistence that making art or making photographs or making images is a special part of understanding who we are as people,” Respini said, adding that a decade later, people are increasingly seeking art grounded in lived experience and reflecting historical and contemporary injustices.

Respini, who is organizing a major survey by Deana Lawson at the ICA in 2021, was a curator in MoMA’s photography department at the time of Greater New York. Although she didn’t work on the exhibition directly, she was influential in organizing New Photography 2009; and with Roxana Marcoci, she cofounded Forums on Contemporary Photography in February 2010, an ongoing series of discussions with curators, artists, editors, and scholars. Those discussions felt urgent, Respini explained, because artists were rethinking the role of photography. “It really felt like there was a shift happening in the medium,” she said.

Courtesy MoMA PS1

When Drew Sawyer, a curator of photography at the Brooklyn Museum, thinks of the year 2010, “I think of a range, or a multiplication, of different platforms for photography.” The publisher Michael Mack founded MACK Books in 2010. Le Bal, the venerable space for photography in Paris, opened in 2010. This was a time, Sawyer said, when many artists were exploring process-based approaches to the medium, “which one could read as a reaction to the digital. But also, as a reaction to the death of those very processes.” Sawyer noted that this “multiplication” of platforms coincided with the rise of the “poetic or lyrical documentary mode.” MACK’s most successful books—Alec Soth’s Songbook (2015), Gregory Halpern’s XXYZX (2016), and Sam Contis’s Deep Springs (2017)—exemplify that lyrical turn in photography. MoMA’s Being: New Photography 2018, organized by Lucy Gallun, represented a triumph of the trend, featuring Contis, Carmen Winant, Matthew Connors, and Joanna Piotrowska; the critic Arthur Lubow labeled Contis’s work in his New York Times appraisal of the survey as “daringly retrograde.”

Sawyer added that 2010 was also the year New York’s New Museum presented Free, an exhibition about the internet, public space, and collective experience. Free, which opened that October, was curated by Lauren Cornell, former executive director of Rhizome, a platform for digital art founded in 1996. (Caterina Fake, cofounder of Flickr, a predecessor to Instagram, contributed to the Free online catalogue.) Where the photography in Greater New York previewed aspects of the social-engagement art that would become integral to museum programming in New York and beyond, Free was more theoretical, and embodied a tenet of Artie Vierkant’s 2010 essay, “The Image Object Post-Internet,” a condition defined as “inherently informed by ubiquitous authorship, the development of attention as currency, the collapse of physical space in networked culture, and the infinite reproducibility and mutability of digital materials.” Free, like other projects, such as Charlotte Cotton’s Words Without Pictures (2009), channeled a spirit of profound introspection around the future of image-making.

Courtesy MoMA PS1

For Xaviera Simmons, showing in Greater New York was “in a tradition.” She recalled that in 2010, the galleries at PS1, a Romanesque former schoolhouse, were “rougher” than they are today, yet the exhibition was as prestigious as an artist residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem or showing in the Whitney Biennial. Simmons had studied at Bard College with Stephen Shore and An-My Lê, and was trained with large-format cameras and analog film. Around 2010, however, she wanted to think about “how a modern photograph could be produced.”

Simmons began collecting pictures online, particularly images of migrants packed into boats and crossing bodies of water, which she sourced from sites such as Human Rights Watch. She worked on them in Photoshop, to make them “my own,” while continually asking larger questions: Who migrates? Who collects? What is the role of the witness? The resulting work, Superunknown (Alive in the) (2010), is a grid of forty framed images, a choral record of perilous voyages. Arriving five years before the images of the migrant crisis in the Mediterranean proliferated around the world, Superunknown remains among the most moving and prophetic works of Greater New York. As the exhibition’s curators noted, Superunknown “renders each individual photograph into a visual metaphor for longing, loss, memory, and despair, both for the image-maker and the migratory participant.”

Courtesy MoMA PS1

One of the last spreads in the Greater New York catalogue is a striking group portrait of the curators and participating artists. Their poses are stylish or ironic or formidable. There’s Hank Willis Thomas in an orange hoodie. Deana Lawson in a navy sweater and bold lipstick. Daniel Gordon in red-and-white stripes. Members of the Bruce High Quality Foundation behind exaggerated masks. Klaus Biesenbach, with his black tie and silver hair, back row center. It’s the kind of assembly that only happens once, and in retrospect, marks the coming together of a generation, a group of artists who, Glenn Lowry accurately predicted, “advance, expand, and overturn notions of contemporary art.”

Any exhibition, especially a sprawling survey, is a message in a bottle. Some drop to the ocean floor. Some return, years later, to our own shores, to the present, full of surprising insights, memories, and wisdom. Looking back, Connie Butler realized that Greater New York did have an impact. “We did get something right,” she said. “It doesn’t always happen.”