What Is a Feminist Picture?

An exhibition at MoMA shows how women photographers have always demanded a seat at the table.

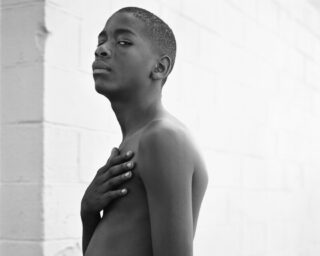

Sharon Lockhart, Untitled, 2010

© the artist

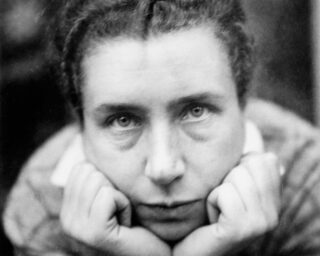

In her book Girlhood (2021), Melissa Febos describes what it felt like as a child to be a body, before she learned to see herself as a body from without: “I would read or think or feel myself into a brimming state—not joy or sorrow, but some apex of their intersection . . . body vibrating, heart thudding, mind foaming.” This overpowering sense of sublimity—absent from the “composure and linearity” of “school bus routes and homework and gender and bedtimes and taxes”—feels connected to her young body. The feeling is a comfort in the face of such dissonance between her inner world and the imposing outer world.

It is a familiar story well told: this inner-outer dissonance, both universal and particular to the challenges a girl faces, to stay close to herself through adolescence and into adulthood in a world determined to will us from subject to object. We might resist by refusing to be seen, by looking back—or, as Febos does, by returning our gaze to our selves.

© the artist

Gazing as both refusal and becoming informs Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum, an exhibition on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Kornblum, a psychotherapist, began collecting the work of women photographers at a time when photography was first being institutionally recognized as a fine art and “maleness was the norm,” as she writes in her catalogue essay. In 2021, she gifted the archive to MoMA in honor of the museum’s senior curator of photography Roxana Marcoci. Ninety of these collected works and a handful of photobooks fill a small room on the fifth floor of the museum, one effort of many made by art institutions over the last half-century to correct the art historical canon. The works were given in friendship, a fact that is unusually highlighted in both the provenance labels and the catalogue. The curator Kathy Halbreich, who introduced Kornblum to Marcoci, writes: “No one talks much about the meaning and impact of friendship on institutions. . . . It’s as if we are afraid of being accused of a lack of critical disinterest or distance if something as subjective and sentimental as affective attachment is broached.”

The show begins with Justine Kurland’s Bathers (1998), an image in which teen girls embody the titular art historical trope, swimming and lounging on rocks in a dappled pond. Febos’s sensory-dizzy narrator might be among them, their freedom exultant, collective yet private—and still, we might sense, threatened. The photo is mounted on a floor-to-ceiling clouded, wavering mirror, beside introductory wall text that asks, “How have women artists used photography as a tool of resistance? As a way of unsettling established narratives? As a means of unfixing the canon?”

© the artist

“The male gaze” has become so commonly referenced as to approach cliché—the sign of a powerful idea. Laura Mulvey’s term—which came out of 1970s feminist film theory—has led to further consideration of what a “female gaze” might entail. One intervention, posed by bell hooks, considers the “oppositional gaze” of Black female spectatorial interrogation; others question the heterosexual female gaze. Some of the work included in Our Selves arguably engages with the notion of a female gaze, but the show does not offer a chronological history or comprehensive account of feminist photography. The wall text explains that instead, “specific constellations of works and ideas” present “an invitation to look at pictures through a contemporary feminist lens.”

“What is a feminist picture?” The question, offered as the title of an online panel held in conjunction with the exhibition, knowingly invites infinitude. Many of the event’s fourteen speakers—including artists in the show such as Susan Meiselas and Cara Romero—wisely did not attempt an explicit answer, in part because feminism itself might be defined as variously as one might picture it.

Documentary photography throughout the show—by Susan Meiselas, Mary Ellen Mark, and others—emphasizes subjectivity, collaboration, and power rather than claiming objectivity or authority.

In her book Living a Feminist Life (2017), Sara Ahmed describes feminism as a collective movement, adding, “A collective is what does not stand still but creates and is created by movement.” Multiplicitous and relational, equally informed by intersectionality and phenomenology, Ahmed’s feminism is about how we move through the world together as bodies. Feminism is often an “experience that begins with sensation.” What is sensed might not immediately be named. But by bringing into the foreground what is so often in the background—things generally assumed unremarkable and therefore unremarked upon, like gender or taxes—a shift in perception can sustain the movement of infinite interpretation. In Our Selves, the camera frames these moments of the invisible made visible to picture feminism—static as an image, ever in flux as a project.

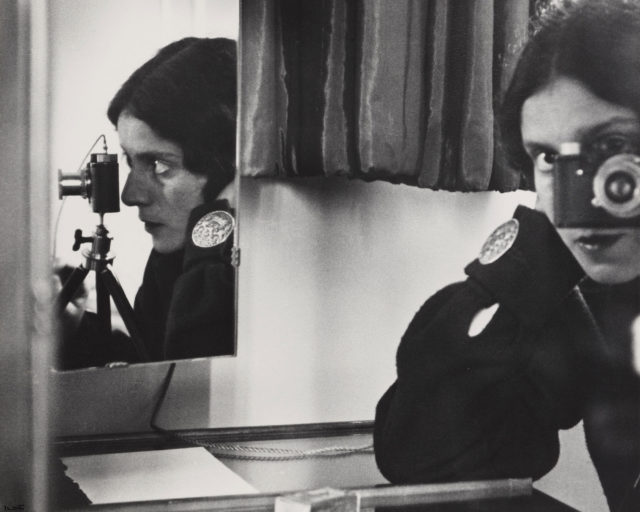

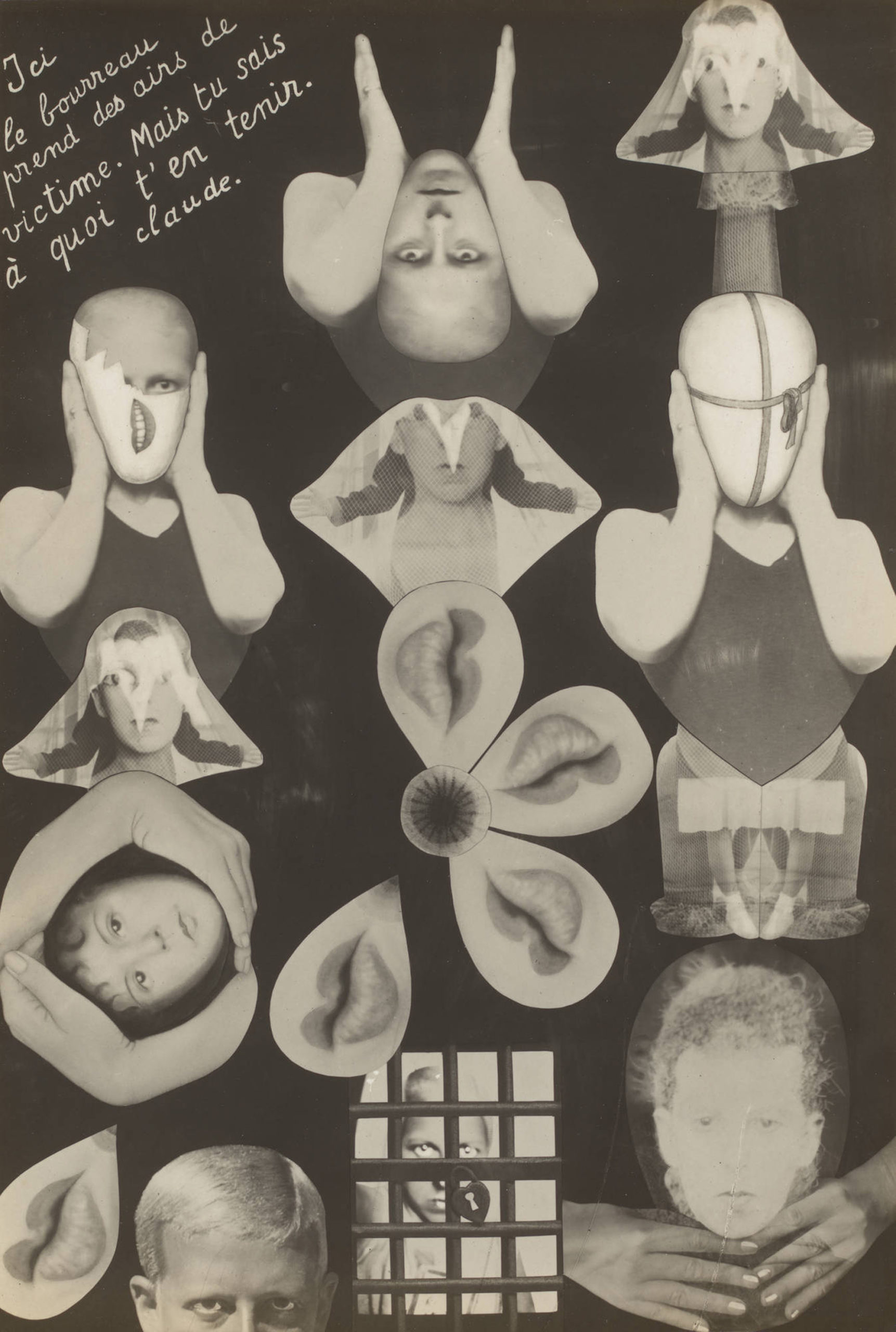

The “constellations” of Our Selves vary between thematic and more associative or conversational clusters. Some images are abstract or conceptual; others are of the natural world. One grouping features mostly early twentieth-century European photographers, including Dora Maar, Grete Stern, Ilse Bing, and Kati Horna. (Many were also present in the exhibition The New Woman Behind the Camera (2021–22), organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.) Here their photos explore the literal and figurative mask, in some cases to anti-capitalist or anti-fascist ends, with mirrors and mannequins, dolls and double exposures, obscured faces and the faceless.

© the artist

Many women photographing in this era straddled commercial and experimental worlds, smudging the boundaries or exploring opportunities for critique from within. Germaine Krull’s The Hands of the Actress Jenny Burnay (about 1930) might have been an advertisement for the delicate ring Burnay wears. Her hands are otherwise unadorned: bare-nailed and crossed in a way that obscures a finger on each, giving the impression of abstraction and a more intimate subject. Across the room, Lorna Simpson’s Details (1996) consists of twenty-one images of close-cropped hands from found studio portraits of Black Americans, each paired with words or phrases. Half learned and carried a gun underline the making of racist stereotypes, while separated and stopped speaking to each other seem to comment on the relationality of all knowledge, including that of ourselves.

Documentary photography throughout the show—by Meiselas, Mary Ellen Mark, and others—emphasizes subjectivity, collaboration, and power rather than claiming objectivity or authority. The images grouped in the catalogue’s chapter “Performance as Ethnography” subvert colonial-patriarchal control even more explicitly. Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie (whose beautiful essay “When Is a Photograph Worth a Thousand Words?” argues for an Indigenous “photographic sovereignty”), created a photocollage as part of her Native Programming series. Titled Vanna Brown, Azteca Style (1990), the image nods to the Wheel of Fortune personality and the dearth of Native representation in media.

© the artist

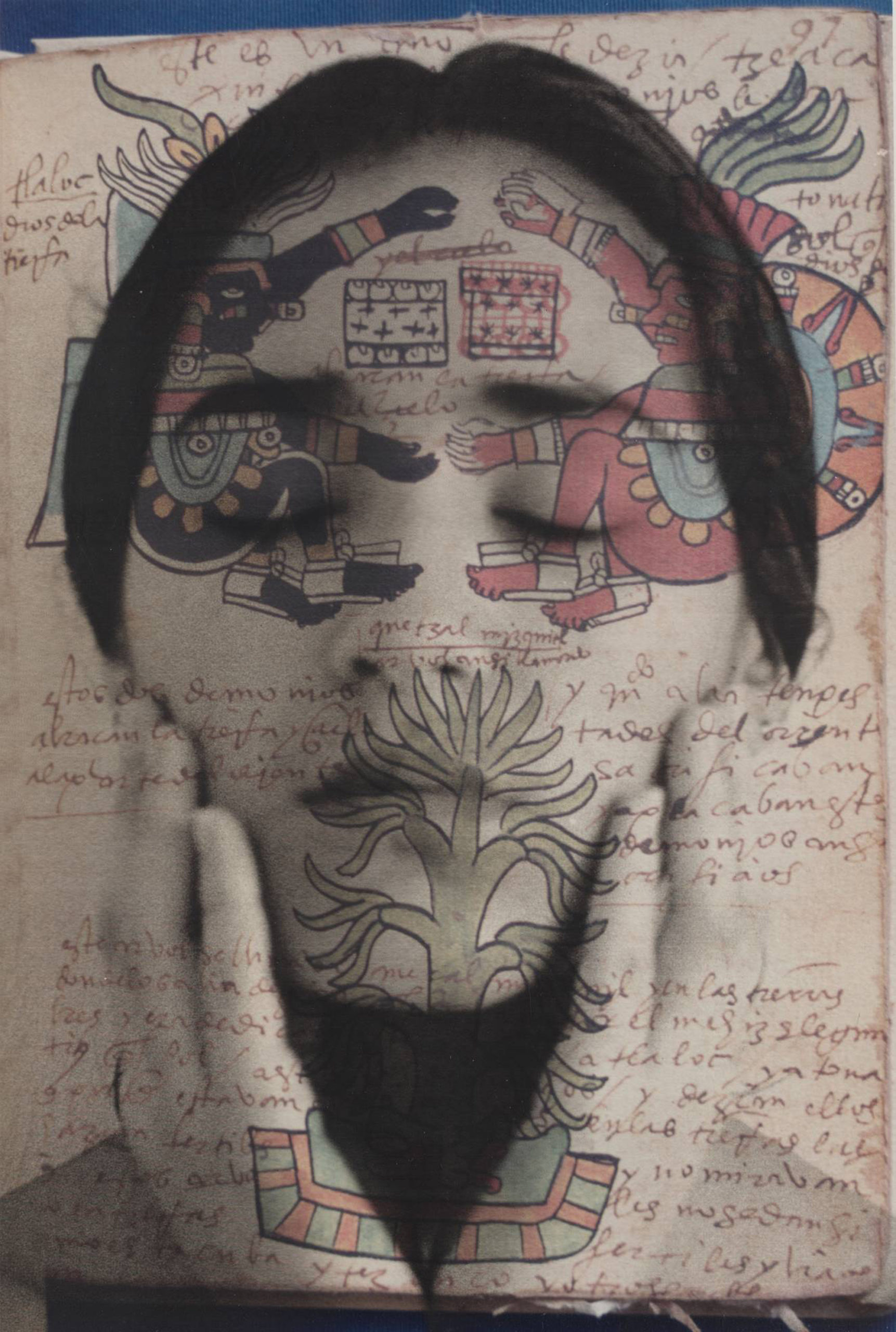

Structural inequality—sexual violence, policed bodily autonomy, pay disparity—may seem difficult to picture. Our Selves includes a variety of approaches. In Tatiana Parcero’s captivating Interior Cartography #35 (1996), the artist’s face is overlaid with the sixteenth-century Tudela Codex that details Mexico’s precolonial Aztec culture. The image shows her with eyes closed, fingers resting on cheeks, an illustration of a cacao tree meeting her closed lips. Nearby, Ruth Orkin’s American Girl in Italy (1951) is a straightforward and strikingly composed portrait of street harassment.

But moving through Our Selves, one might begin to see the structural—the background, coming into foregrounded focus—everywhere. An image from Carrie Mae Weems’s Kitchen Table Series (1990) shows the artist’s alter ego sitting with a daughter figure at the table, both applying lipstick before their own vanity. It is a moment of private ritual and maternal care, the performance of gender, an assertion of Black female beauty in relation to the gaze, and more. The series came out of Weems’s search for her own voice. In the audio guide she reflects on using her own domestic space: “What I’m suggesting really is that the battle around the family, the battle around monogamy, the battle around polygamy, the social dynamics that happen between men and women—that war gets carried on in that space.”

© the artist

In her work, Ahmed often invokes phenomenologist Edmund Husserl’s “writing table” to queer it. She considers the kitchen or dining table, recalling A Room of One’s Own and Kitchen Table press to reflect on how long women have understood, by necessity, how tables are multiuse. Women have also understood the work that goes on behind them, out of view. Of the Kitchen Table Series, curator Adrienne Edwards has written: “There are moments when Weems clearly resists the ordering device that is the table—lying across it, leaning against a wall—and through serial images and a polyphonic voice we come to see how the figure comes to know and feel herself, affirming or countering our impressions of her.”

We are often made responsible for coming to our seat at the table. But we might demand that the table change if we are to sit, or we might change the table by sitting. Perhaps we ourselves are the site—or sight—of change. Catherine Opie’s Angela Scheirl (1993), of Scheirl against a rich red background, in a dapper suit, bright socks, and long shoes that command our attention, is a “portrait of becoming,” writes Dana Ostrander, a curatorial assistant at MoMA, in the catalogue.

Photograph by Robert Gerhardt

Queerness, in all the fullness of its meaning and possibility, also grants an understanding of the self with the permission to change—to become. Opie’s portrait of the Austrian artist and filmmaker, who would later go by Hans and now Ashley Hans, is a testament to the temporality and fluidity of self. Claude Cahun, whose work was largely overlooked until the 1990s, made complex Surrealist collages in collaboration with their lover and stepsister Marcel Moore. Cahun famously wrote in their 1930 “anti-memoir” Disavowels: “Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” Their acute work playfully and presciently explores the multiplicity of the self, anticipating later feminist theory including, Marcoci writes in the catalogue, Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble (1990).

The sheer physicality of two pieces on the back wall is memorable. In Jeanne Dunning’s Leaking (1994), what seems to be tomato flesh appears—joyously, erotically—in the place of a woman’s tongue. The portrait is framed beside that same wet red in close-up, both images ovular, like giant locket portraits. Amanda Ross-Ho’s Invisible Ink (2010) is a ghostly imprint of the artist’s body, first made accidentally and then embellished, including with cut-out eyes that hauntingly penetrate.

© the artist

All works courtesy The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Helen Kornblum in honor of Roxana Marcoci

As the narrator’s body in Febos’s Girlhood begins to change, bumping up against the world’s expectations and desires of her (“My hips went purple from crashing them into table corners,” those unyielding ordering devices), she begins to experience shame more than that exhilarating embodiment of the sublime. She learns to fit herself, over time and to painful consequence, around such obstacles and demands. She learns to see from another’s eyes rather than her own. Febos finds her way back to herself, just as in Our Selves, women and gender-nonconforming photographers make their way through seeing, unseeing, and seeing anew. One woman’s life’s work—a collection of the labor of many, given to another in friendship—is a gift of sight seeking self and of self seeking sight.

Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, through October 2, 2022.