What Is the Environmental Cost of Photography?

From the daguerreotype to the iPhone, “Mining Photography” explores how the exploitation of labor and the environment has always shadowed the medium’s history.

Ignacio Acosta, Computer Aid, 2015

© the artist

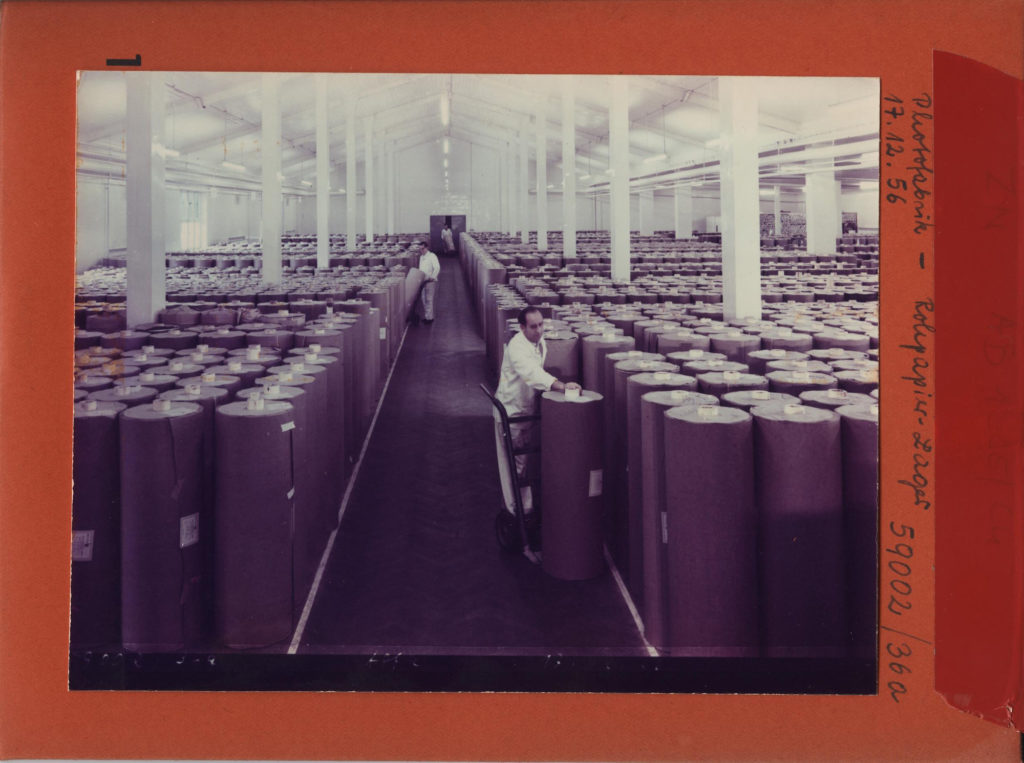

Over the past twenty years, the rhetoric of corporate-driven globalization has spun a fantasy about the digitalization of images, as if we have entered the epoch of dematerialized photography. Undoubtedly, we print photographs less frequently than we used to, yet the ubiquity of the smartphone means that today far more photographic images are being produced, as well as exchanged via networks and stored as data files. Today’s glut of digital images may seem divorced from the previous era of the negative-based print, yet excess characterizes both eras at the levels of circulation and production. Analog photography was tremendously resource-intensive, just as digital photography relies on the proliferation of mobile devices that employ approximately seventy-five elements from the periodic chart to function.

Courtesy the artist

How can we account for the continuities between analog and digital photography, and their shared problem of overabundance? The exhibition Mining Photography: The Ecological Footprint of Image Production, recently presented by the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Hamburg, Germany, addresses various topics such as these about the supply chains of the medium. It contains archival photography and the work of nearly two dozen modern and contemporary artists and collectives, including Mary Mattingly, the Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio, Madame d’Ora, Robert Smithson, Simon Starling, and Anaïs Tondeur. Emerging from the exhibition, which will travel over two years from Hamburg to Vienna and Winterthur, Switzerland, the accompanying catalog features a half-dozen highly engaging and informative commissioned essays and a series of conversations between historians, curators, and creative practitioners.

Eastman Kodak Company

Agfa Collection, Museum Ludwig, Cologne

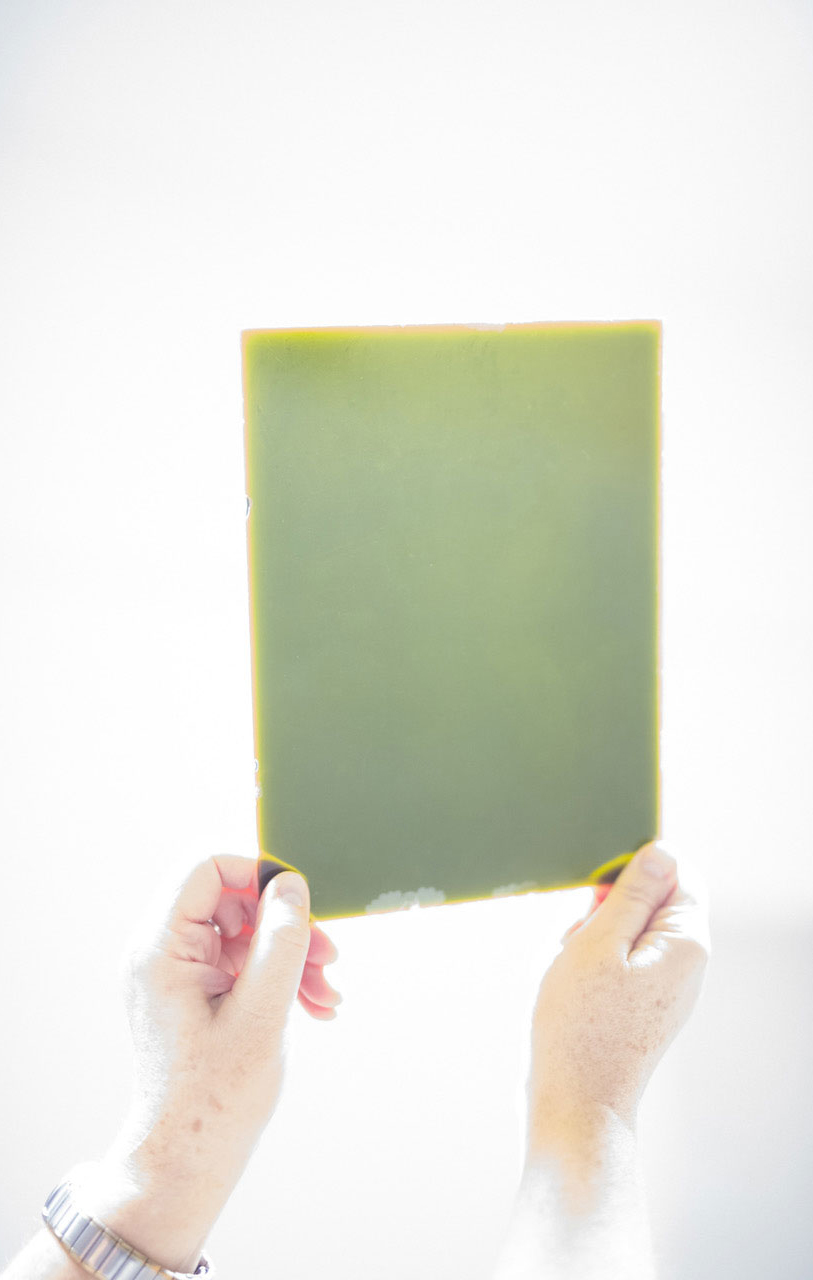

The book is a superb primer on how to understand the material substrata that make photography possible: the copper, bitumen, silver, albumen, gelatin, cotton rag, and celluloid of the analog, and the lithium, cobalt, and other so-called rare earth elements used in today’s magnet-based digital devices. As Nadia Bozak points out in one of the volume’s essays, there are hidden and invisible forces and histories behind how a photograph presents what is before the lens. One chronic suppression is how the image came to be created at all: for example, how the camera and recording technologies were assembled and produced.

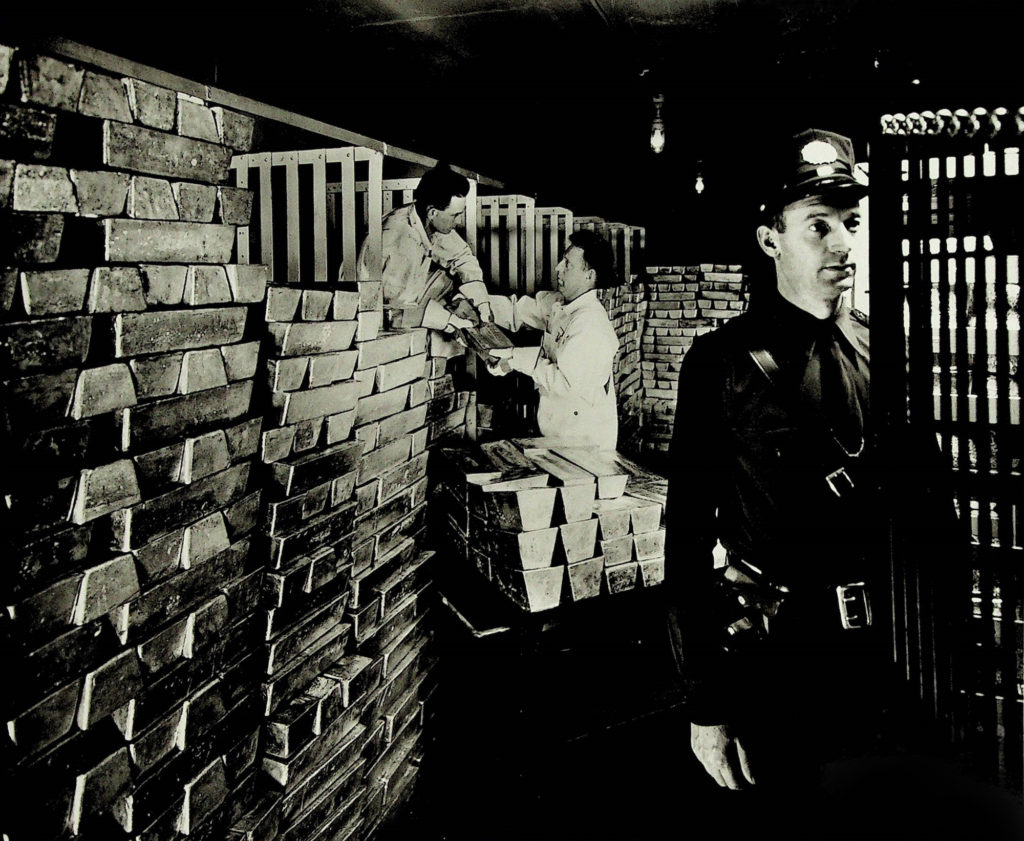

Fossil fuel is always among the primary unseens of photography. The invention of the medium coincided with that of the steam engine and large-scale factory production, which relied on coal, peat, and later petroleum power. For how else other than with steam-powered mining equipment and transatlantic steamboats do you import all that silver from mines in Bolivia to Berlin, Antwerp, or Rochester, New York, to coat paper with photosensitive silver salts? How else, without logging operations fueled by coal- or gas-powered vehicles, do you gather all the hewn logs to be pulped and boiled in sulfuric acid to make cellulose paper?

© the artists

As the nineteenth-century marched on, machinery to transport and process these materials needed to be assembled and deployed, originating in yet more fossil fuel–powered factories. Sometimes, as with photogravures that coated paper with asphalt or bitumen to print using soot dust, the image became an artifact of pollution and energy consumption. Mining Photography also points to other fascinating circularities, such as how the mercury used in gold-washed, copper-plate daguerreotypes continues to contaminate streams in the Western United States where itinerant photographers set up studios to cash in on boom-time gold miners’ portraits.

The outsized appreciation given to individual photographers in the story of photography’s origins neglects the key role of trade networks, resource depletion, and labor struggles.

What if we were also to examine, as Katherine Mintie does in her insightful conversation with Mining Photography’s editor Boaz Levin, “the material networks and the production of photographic goods . . . to recognize the labor of those who are often marginalized in photographic histories—women, the enslaved, the working class, and even animals”? The outsized appreciation given to individual photographers, many of them white and male, as Mintie points out, in the story of photography’s origins neglects the key role of trade networks, resource depletion, and labor struggles in supporting the physical and discursive apparatuses of image creation and circulation.

© Holt/Smithson Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Take, for example, those animals Mintie refers to—chickens, pigs, cows, and horses. Mining Photography directs readers to consider the material reality of photography, like the billions of eggs required to produce albumen papers. Levin also points out that “as late as 1999 Kodak was still processing over thirty million kilos of cow skeletons every year,” their skins and bones rendered into gelatin, the main fixative of photosensitive paper.

And consider the enslaved workers who mined the copper, gold, and silver for daguerreotypes, and later, the tons of silver needed to embed in that gelatin-coated paper. Or the enslaved who grew and picked the cotton, later woven into textiles by women and children in mills, fabric that eventually found its way into trash collected and sorted by largely female, underaged, or elderly ragpickers, and that was eventually bleached and boiled by women who worked in factories to produce rag paper. How manual labor became divorced from the labor of authorship—anonymized as merely “raw” production against “refined” artistic creativity—is the cornerstone of this story.

Trinity College Library, Cambridge

© the artist

Mining Photography presents a fascinating case study of a trove of 1860s cartes-de-visite of so-called pit brow women of Britain’s coal mines, collected by the poet Arthur J. Munby, who also commissioned several examples. The images are a striking departure from Victorian-era stereotypes of femininity, as the miners stand in sometimes fancy-looking studios wearing dirty, rolled-up jeans and holding the pans and shovels of their trade, or sit, legs spread wide, on wheelbarrows. In their work clothes, staring frankly out to viewers with nonplussed gazes, they make visible the labor of production behind modernity’s comforts.

The book’s pages are interspersed with unsigned archival images, such as those of the “pit brow” women, and with contemporary works that explicitly share authorship with nature. One could say that photography, as an indexical medium capturing subjects external to the camera, and doing so by relying mostly on sunlight, has always “collaborated” with nature. In the case of Tondeur’s work, the artist creates a printing medium using soot caught in respirators that she wears in highly polluted areas. Her process references the photogravure method of using coal or bitumen to produce a carbon medium for the image. Her images of the sites, which are shown with the respirators and vials of particulate matter, labeled to identify the areas where she sampled, are utterly dependent on invisible aspects of the landscape in a way that most photographs are not.

© the artist

© Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio

Projects that take up digital photography are likewise concerned with the materiality of the image-capture process. They focus on how technology companies that produce lithium-battery-powered devices with high screen luminosity aspire to literally outshine their ethically suspect and largely hidden back-end supply chains. Mary Mattingly’s work on cobalt mining in the United States and the Democratic Republic of the Congo represents the mundane realities of the material. It appears in one photograph as a rather unassuming silver-gray metal; flow charts depict its byzantine interpenetration of nearly every aspect of contemporary existence: the rechargeable batteries in tablets, phones, cameras, laptops, and electric cars, as well as cobalt’s presence in industrial chemicals and dental and surgical equipment.

© the artist

Supply chains are rooted in trade networks that rely on the rapid and reliable circulation of goods, often without explicitly marking that complex process as part of the consumer’s purchase. Beyond the standard back matter credits, however, the book initiates no conversation about the materials and supply chains that contributed to the production and distribution of the physical volume itself, which would have presented an interesting moment of self-reflection about the often-globalized reality of contemporary publishing. This oversight notwithstanding, in its timeliness and historical depth, Mining Photography provides a much-needed corrective to many blind spots of production in the consumer economy.

Mining Photography: The Ecological Footprint of Image Production was published by Spector Books in 2022.