What Was the NFT?

When cryptocurrency was on the rise, entrepreneurial artists and prominent photographers rushed to release NFTs. But is the NFT actually a medium—or merely a medium of exchange?

Kevin McCoy's NFT Quantum, 2014, in Natively Digital: A Curated NFT Sale, Sotheby's, 2021. Quantum, which sold at auction in 2021 for $1.4 million, is considered the first artwork ever minted. Photograph by Timothy A. Clary/AFP/Getty

In the winter of 2021, it was hard not to suspect that the world had produced a wholly novel lament. That December, the art dealer Todd Kramer took to Twitter and cried out: “All my apes gone.”

The apes in question—for those who were not terminally online during that phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, were not the majestic beasts that have fascinated primatologists like Jane Goodall and Frans de Waal (though those, too, are in danger of being gone). Rather, Kramer was referring to his collection of Bored Ape Yacht Club (BAYC) non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, which had been stolen from him by an enterprising hacker. (NFTs are unique digital objects that have been indelibly recorded on the blockchain, a decentralized ledger that is the backbone of all cryptocurrency and digital collectible transactions.) Part of a collection of ten thousand unique cartoon chimps, whose faces sport lackadaisical pouts and yawns, smug grimaces and manic grins, and who come with a dizzying array of clothes and accessories that are randomly combined to create a chucked-in-a-blender mélange of looks, Kramer’s band of apes were then worth an eye-watering $2.2 million.

This was during the heady days of the 2021 NFT frenzy, when fortunes were made and lost and sometimes made again in mere days. Everyone, it seemed—celebrities, fly-by-night financial wizards, credulous day traders—was thirsting for a piece of the lucrative market in monkey JPEGs. (Collectors are currently suing several bold-faced names, including the late-night host Jimmy Fallon and the pop star Justin Bieber, along with the auction house Sotheby’s, for allegedly promoting the project “misleadingly” and colluding with BAYC creator Yuga Labs to artificially inflate prices.)

It wasn’t just Bored Apes. People clamored for CryptoPunks, Doodles, Cool Cats, Azukis, Pudgy Penguins, and more. Buyers snapped up so-called “generative-art” projects—collections of related yet subtly unique images made by creatively coded algorithms—like Tyler Hobbs’s Fidenza and Erick Calderon’s Chromie Squiggles. Blue-chip artists like Jeff Koons, Urs Fisher, Takashi Murakami, and Damien Hirst jumped on the bandwagon. New collectors flush with crypto cash swooped in and transformed the lives of previously unknown artists with the click of a button. Who could forget the meteoric rise of Beeple (aka Mike Winkelmann), whose massive NFT collage Everydays: The First 5000 Days (2021) sold at Christie’s for $69 million? Once the fire hose of money got turned on, it seemed like anyone could have a drink.

During the hype, photographers were eager to join the NFT circus too. Outside of digitally native art like Bored Apes, whose commercialization and monetization via NFTs was something of a no-brainer, photography was the medium most ripe for an NFT crossover. After all, most photographs are consumed through screens now. Why not sell them that way too?

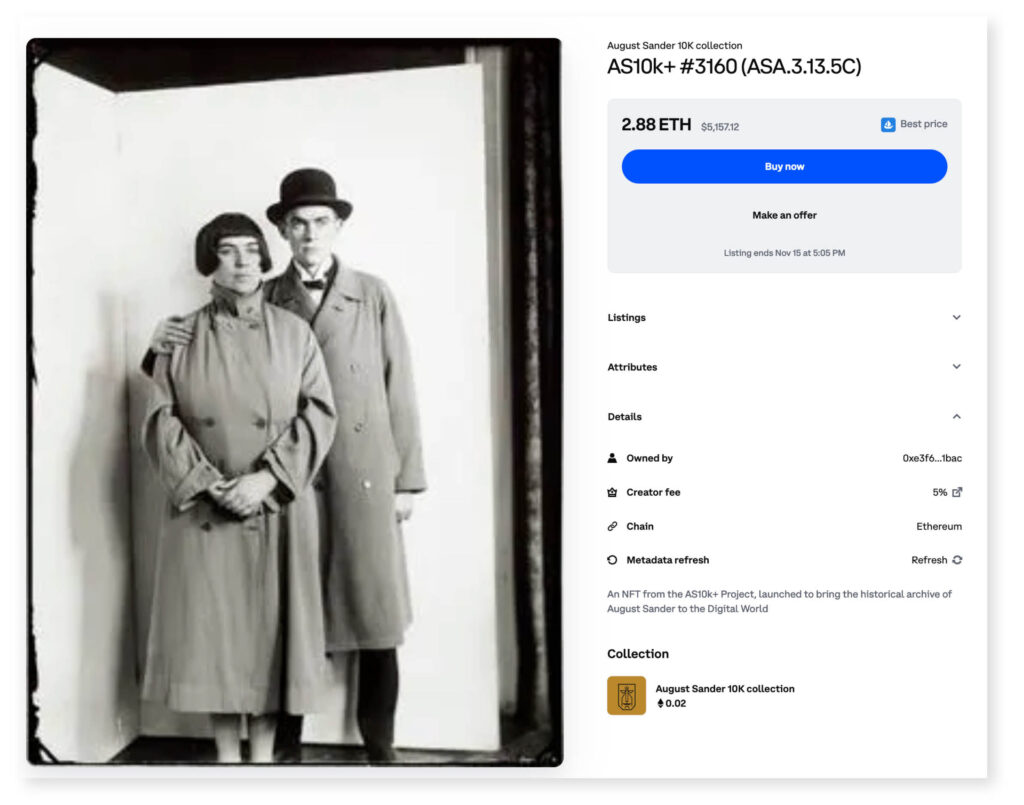

Photography’s push into the cryptosphere saw prominent artists—Joel Sternfeld, Gregory Crewdson, Alec Soth, Joel Meyerowitz, and others—dig into their archives to unearth unseen pictures, whether to tokenize ephemera such as production stills or release older projects in NFT form. There was even an attempt by Julian Sander, the great-grandson of August Sander, to enshrine the entirety of the eminent photographer’s output—over ten thousand photographs in all—as a collection of NFTs, which has resulted in an ongoing legal battle. Others, like Justin Aversano, whose lackluster project Twin Flames (2017–18) gained a baffling amount of market momentum, became overnight sensations. Perhaps these photographers were motivated by a true interest in the blockchain’s brave new world. But most, I suspect, were seduced by the opportunity for a quick cash injection.

Unlike the market for painting and sculpture, which has come roaring back after the 2008 crash, the market for photography has recently been in a bit of a slump. (This remains the case despite the notable efforts of the fledgling photography-focused art fair Photofairs New York, and a smattering of recent expectation-defying auction prices fetched by significant historical works like Man Ray’s 1924 Le Violon d’Ingres, which sold last year for a record-breaking $12.4 million at Christie’s.) Collectors, it seems, have lost some of their taste for photographic prints. At the same time, economic headwinds for photographers have been picking up: the cost of producing and framing a photograph, which has always taken a bite out of photographers’ comparatively thin profit margins, has been pushed ever higher; teaching jobs have become simultaneously more competitive and lower paid; lucrative commercial work looks increasingly threatened by artificial intelligence. No wonder so many photographers jumped at the chance to make NFTs. It was one of the few places where the money was.

The mere idea of photography being bought and sold as an NFT is likely to raise the hackles of connoisseurs of fine photographic prints and other members of the photo world’s old guard.

The crypto crowd is fond of pithy mantras. Those who didn’t believe the hype were told to “have fun staying poor.” When speculators are asked about the rationale for purchasing a particular NFT or altcoin (the catchall term for non-Bitcoin cryptocurrency), they might respond simply, “Because number go up”—a line that provided the journalist Zeke Faux with the title for his recent book Number Go Up: Inside Crypto’s Wild Rise and Staggering Fall. But numbers can’t go up forever. In 2022, the prices of both cryptocurrencies and NFTs spectacularly collapsed, immolating untold amounts of wealth and leading most sane people to strongly question the wisdom of spending sums more commonly associated with the purchase of, say, a Learjet or a chalet in Gstaad.

Now, as we survey the rubble, the landscape appears bleak. At the market’s peak in January 2022, global sales of NFTs reached $5.7 billion dollars, according to DappRadar; by May 2023, that number had dwindled to $675 million, a decrease just shy of ninety percent. The biggest NFT sales event of this year so far, a Sotheby’s auction entitled “Grails: Property from an Iconic Digital Art Collection Part II,” pulled in a respectable haul just under $11 million. But it was tainted by the fact that it was organized by an advisory firm handling the liquidation of disgraced crypto hedge fund Three Arrows Capital, which made the event feel less like a white-glove evening sale than like a police auction. Recent analysis by dappGambl, a crypto-gambling and gaming-analysis website, concluded that 95 percent of all NFT collections are now effectively worthless.

Galleries that had dived headfirst into the NFT space, like Galerie Nagel Draxler in Germany, appear to have either stopped their crypto-based programming entirely, or radically throttled it. Last summer, Takashi Murakami issued a public apology after his Murakami.Flowers NFT collection experienced a spectacular peak-to-trough price collapse of 99.2 percent. And after the bottle-popping, Lambo-flexing, NFT hypefest that was Art Basel Miami Beach 2021 and the calculated pomp of Art Dubai Digital 2022—during the boom, the UAE emerged as the premier tax haven for the crypto rich—the new art-market trend seems to be a reversion to the safest bet for minting money: painting, painting, painting.

Nevertheless, some have kept the hope alive. Kenny Schachter, an artist, collector, and prolific arts journalist, has emerged as one of the foremost cheerleaders of NFTs. During the boom, he wrote incessantly about them in his regular column in Artnet and extolled their virtues to his legions of Instagram followers. He also made and sold them, both through traditional galleries and online NFT marketplaces like Nifty Gateway. (His first round of sales, he tells me, netted him three hundred thousand dollars.) Famously, he even had the name of his one-man art movement, “NFTism,” tattooed on his arm. After the market crashed, he amended it to read “post-NFTism.”

Schachter believes that the NFT space is “in the healthiest, most beautiful place it’s ever been.” Indeed, he sees this moment in NFT history as an echo of the art world of the 1990s. “When I started out in the art world, there was a recession where the market didn’t constrict, it all but evaporated,” he tells me. In his mind, the implosion of the market brought with it a kind of cleansing fire, burning away the dross. “A lot of the adult population, when it comes to making money in crypto, is reduced to infants,” he says. “They’re like limited-edition tchotchke thingies that you can buy and sell with your friends, like baseball cards for rich people.”

Absent this kind of speculative buffoonery, real creativity and community will be allowed to flourish, he assures me. Schachter and others I talked to were particularly keen to emphasize the communal aspect of the NFT scene, where virtual camaraderie on Discord has taken the place of boozy exhibition openings, and direct access to artists is assumed to be part of the package, rather than the exclusive privilege of, say, those who get invited to the gallery dinner. “Art is a means of self-expression, and a crucial conduit to relate to other people,” Schachter says. “I can’t imagine anyone who ever made art with a digital inclination before the collapse stopped doing so then.”

Courtesy Assembly

Shane Lavalette, a photographer who is also the former director of Light Work and founding director of Assembly, a gallery focused primarily on photography and video in Houston, and Assembly Curated, which he calls the “first curated fine-art photography NFT platform,” would tend to agree. “In terms of a longer timeline, I feel like we are still very early in the emergence of a technology,” he tells me. “Digital collecting is not going to be something that’s less a part of our lives as we go forward, it’s going to be more a part of our lives. And the technology that was introduced makes that very easy when it comes to the things that we need to create and collect digitally, which is authenticity and ownership and provenance.” Notably, Lavalette also points to the usefulness of NFTs for securing royalties for artists when their work, whether digital or physical, is resold on the secondary market, a transaction that can be coded into an NFT’s smart contract, which is a computer program written into the blockchain that is designed to execute automatically. (After a 2018 ruling by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in San Francisco struck down the California Resale Royalty Act, artists are no longer entitled to receive royalties on the resale of their artwork anywhere in the US.)

The mere idea of photography being bought and sold as an NFT is likely to raise the hackles of connoisseurs of fine photographic prints and other members of the photo world’s old guard, but Lavalette sees the development as part of a continuum that stretches back to the medium’s origins. “I think the medium of photography has been intrinsically linked to technology since its beginnings,” he says. “And we’ve seen all of these moments with, you know, the emergence of digital photography, people rejecting that as actually being photography, and then ten or fifteen years later, those same people shooting with a digital camera and it not being a question.” But Lavalette doesn’t assume that NFTs will supplant old modes of photographic distribution and display. “Yeah, I definitely think of it more as an addition,” he says. “And photography is a medium that is well suited to existing in many forms.” As for the question of the NFT’s appeal over more traditional forms of collecting photography, Lavalette admits that sometimes it’s the draw of a hot new technology, while other times it comes down to more practical concerns: “As a collector, you can, in a way that’s actually very efficient, kind of have a stake in an artist’s cultural capital. And, that’s something that’s not going to appeal to everyone, right? For people who it does appeal to, it’s extremely exciting, because you don’t need storage space.”

It seems clear that even after the market apocalypse, artists will continue to mint NFTs and collectors will keep collecting them (though in what quantities is still anyone’s guess). But a fundamental question, which seemed to be lost on everyone during the hype cycle, remained unanswered for me: Is the NFT actually a medium, or merely a medium of exchange?

Courtesy the artist

For an answer on the photography front, I turned to Alejandro Cartagena, an artist, publisher, and infectiously enthusiastic NFT advocate who has cofounded two photography NFT platforms: Obscura, where he is currently an advisor, and Fellowship, where he now works full time. Cartagena began by turning my question around, asserting that photography is a medium that has an ambivalent relationship to its materiality in the first place. “As a commissioned artist,” he tells me, “I get sent by the New York Times to do pictures, and I send them back ten JPEGs. They send me digital money for those JPEGs. So in in essence, I’ve been selling NFTs for quite a while. It’s just that we didn’t call them NFTs.” There is nothing inherent in a photograph that dictates the fine-art print must be its final—collectible—form. Once a photograph is taken, it becomes a kind of wandering image, in search of a home. So, in a digital world, why couldn’t that home be the blockchain? “Maybe we’re ready to think of photography as this unsettling medium that doesn’t have a native thing for it,” Cartagena says.

Cartagena did acknowledge, however, that photographers were not taking advantage of the expanded possibilities of digital distribution nearly enough. This is something he and his cofounders at Fellowship are looking to remedy. One project he described, which strikes me as truly novel, is a collaboration with the photographer Joel Meyerowitz, called Sequels. To make it, Meyerowitz arranged 3,650 previously unseen images from his six-decade archive into a preposterously long, playfully associative sequence. With the help of a custom smart contract, Fellowship is currently in the process of minting one of the images in this sequence per day and putting it up for auction, so that collectors can, it is hoped, not buy only individual images but smaller subsequences of photographs from the larger whole. The minting process of the entire sequence will take a decade, making it something like the miniature visual equivalent of a concept-driven long-haul composition like John Cage’s Organ2/ASLSP (As Slow as Possible), a performance of which is currently underway in Germany and is slated to last another six centuries.

But such projects are still few and far between. When I talked to Brian Droitcour, the editor in chief of the high-toned fine-art NFT platform Outland, he described a few NFT projects for which custom-designed smart contracts were fundamental to the work itself but generally took a more utilitarian view. “I think their main use is just as an editioning technology for digital art,” he tells me. “A lot of people in the art world say they hate the phrase ‘NFT art,’” he adds, “because it doesn’t really refer to the medium in the way that talking about, like, video art does. But it’s about the social and economic environment in which that art circulates. Think of it as an analog to, say, something like ‘contemporary art,’ which doesn’t really say a lot about the work, but it does put it in this field of museums and galleries, and art magazines and art schools, and sets it apart from people who are just painting landscapes.” In other words, NFT art is not a medium, it’s a milieu.

How, then, can we sum up the NFT milieu, at this point in its young life? It was, on the whole, a reflection of the culture at large, which increasingly rests on the cornerstones of greed and grift. (It is not a coincidence that quadruply indicted former president Donald Trump, avatar of these particular vices, issued his own collection of NFTs after leaving office.) It was also, like the crypto boom more generally, fueled by desperation. Vast numbers of people hoped that they, too, could flip enough monkey JPEGs or Dogecoin or what have you to have a chance at a comfortable, dignified life, as the writer Sarah Resnick brilliantly chronicled last year in an essay for n+1, entitled “Walk Away like a Boss.”

For all its unseemliness, excitement generated by NFTs produced a little bit of good too. “Regardless of what happens to the market,” Tina Rivers Ryan, a curator at the Buffalo AKG Art Museum who specializes in digital art, tells me, “it’s gratifying to know that at the very least, NFTs appear to have helped broaden the audience for digital art within the mainstream contemporary art world in the long term, and that some artists were able to reap benefits in the short term.” As for the great mass of people who were convinced that they were buying into the next great revolution in art? Well, most of them got stuck holding the bag.