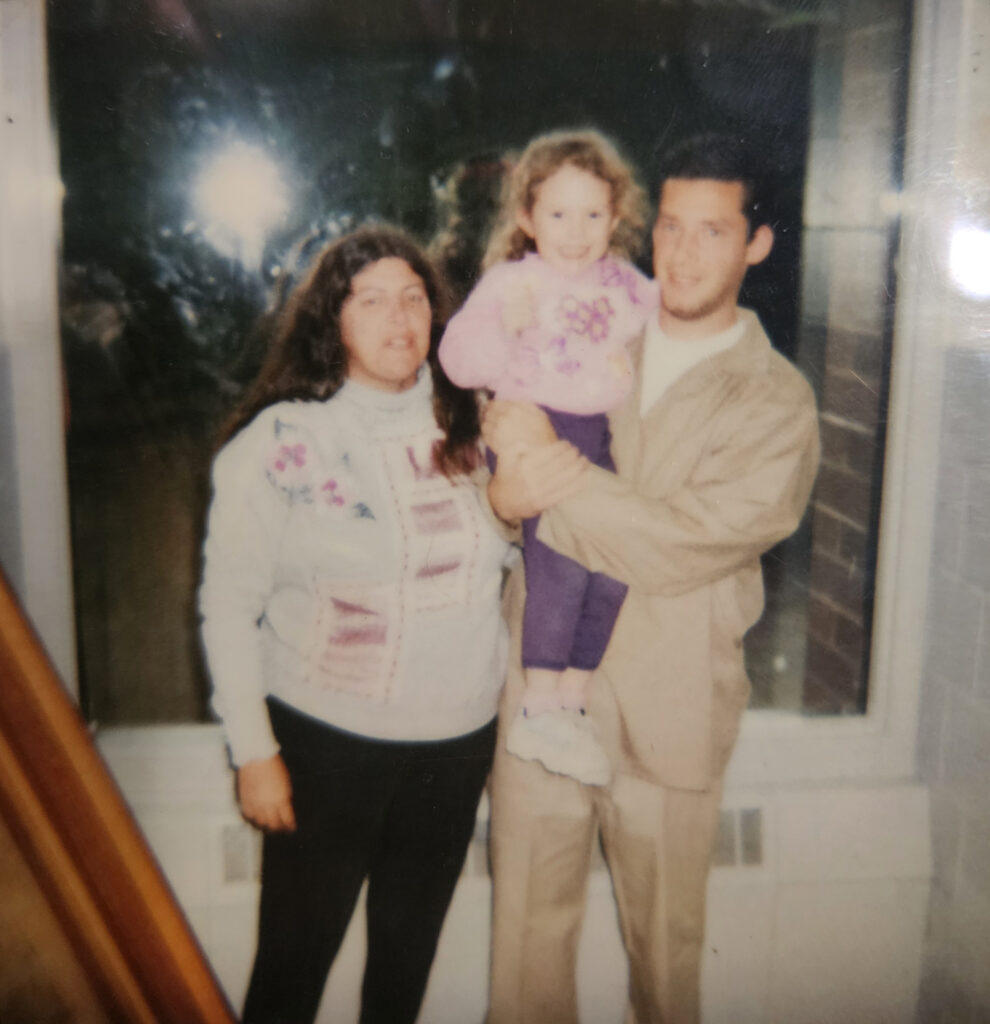

Derek LeCompte (right), with his father (left), ca. 1990s

The oldest photo I have is of my father. My aunt Terry sent it to me fifteen years ago. My dad and I never had a loving relationship, and I never shook the bitterness I held for him. He was a hard man who never quite figured out how to be loving. He was distant and, probably because of his alcoholism, sometimes cruel.

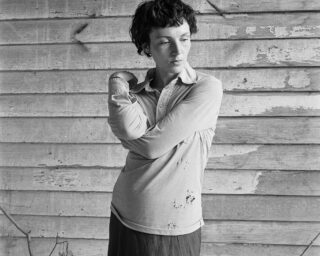

I had shared that hurt with my aunt. In response, she sent me an elementary school photo of my dad to reveal another side of him. In the picture I saw an unsmiling boy trying to mask his pain.

My father had a blind eye from a childhood injury, with only whiteness in it. He was sensitive to people staring at his eye, so I can imagine how mean kids were about it growing up. He probably became hardened as a strategy for coping with the way his peers treated him. Through this photo, I developed a new connection to my father—relating my own personal suffering to the pain he had experienced. The picture reminds me to find sympathy for everyone, even people who have harmed me.

In prison, photos are some of the most cherished treasures we have. We lose so much to incarceration; photos are a safeguard against further loss. I have hundreds kept in photo-albums that I dressed up like scrapbooks. I also taped some to the bottom of the bunk above mine so I see them every time I wake up. Those pictures are of the people I love most.

Now that I have an electronic tablet and electronic messaging, it’s easier for people to send me photos. I frequently scroll through pictures on my tablet for a refresher. But there are a few prized photos, in particular that I hold so dear I refuse to give them up.

One of those gems is a photo of my father and grandmother dancing at my parents’ wedding. It brings a smile to my face because my grandmother looked beautiful; other than that picture, I’ve never seen her wearing a nice dress, with her hair styled. She had a smile on her face as she danced with her boy.

The photo also makes me laugh because it reveals how much my father idolized Elvis. He only loved two things: Elvis and country music. He had the same hairstyle and fashion sense as Elvis, but he looked like a heavier version of the rock star. I like to imagine that the reason my dad is smiling in the image, which he rarely did, was because they were dancing to country music or Elvis.

I have quite a few photos of my sister Christina, who was an infant when I was arrested. I only met her after I was sent to prison. She means the world to me. Most of my photos of her are posed and formal, but the one I love most is a picture in which she’s acting goofy and scared by a T-Rex at Universal Studios in Orlando.

She was able to go places I never got to visit, so I have enjoyed living vicariously through her. My mother took the photo as my sister threw her hands up in an “oh my God!” pose with a silly face. Seeing my sister in her naturally goofy state warms my heart because I would have been doing the same thing with her if I had been there.

Unfortunately, over the last quarter decade, I’ve changed prisons several times and lost a few cherished photos. This has been devastating.

A photo I wish I still had is of my mother standing in the grass outside of her home from before I was born. She’s barefoot in what I would call a hippie outfit with bell-bottoms and a frilly white blouse, wearing a bunch of bracelets and a flower in her hair. She looked stunning in the photo, happy and smiling broadly. There was a radiance to my mother I had never seen.

She was a hippie, so maybe she was a little high. But I sometimes feel like I took that radiance away from her because she never smiled at me that way. During my time with her, I remember my mother having a sad plainness to her. She didn’t try to dress with any particular flair, style her hair or even accessorize her outfits. That’s why seeing her in this different light was so meaningful to me.

The other photo that comes to mind is another one of my father. An uncle sent it to me to prove my father didn’t always lack a fun personality. It was a photo of him in his early twenties. He’s wearing bright orange bell-bottoms and a super-tight silk shirt.

He tried so hard to be fun in this photo, but he still looked miserable. Someone probably convinced him to let them dress him up. Anyone who has ever tried to dress a cat in a costume knows the look I’m talking about—pure misery and an expression that says, “Take this damned thing off of me!” When my dad found out my uncle sent the photo to me, he ordered me to burn it. He was too embarrassed to have anyone see him in bright orange bell-bottoms.

All photographs courtesy Christina VanGaasbeck

I had that photo up until I was transferred to my current New Jersey prison in 2018, where it was yet another casualty of a transfer. I like to think my father paid a guard to “lose” it.

When you spend decades locked up like I have, you learn that loss is at the core of prison life. I’ve been incarcerated since I was nineteen, for more than twenty-five years. Since then, I’ve missed out on a lot of things, and I’ve lost all of my grandparents and parents. That’s why I hold on to pictures of them. I can no longer make new memories, or have new moments to capture with them, and the photos I’ve lost are gone forever.

Over time, memories of my parents and grandparents are fading too. I try to preserve those memories by closing my eyes and envisioning them, but some memories have gotten fuzzy. Memories often bring solace in prison, so capturing them in photos brings a layer of permanence. Remembering cherished moments is the best I can do to shield myself from how swiftly time passes on the outside.

But even more than that, those captured moments are a reminder that life is full, and there are going to be opportunities to make new, joyful memories in the future. Maybe those memories will be just as meaningful to someone else.

This article is copublished with the Prison Journalism Project.