Why the Visionary Designer Willi Smith Is More Relevant Than Ever

Smith built one of the most influential fashion brands of the 1980s. An exhibition illustrates the breadth of his talents—and the limits of how fashion is chronicled.

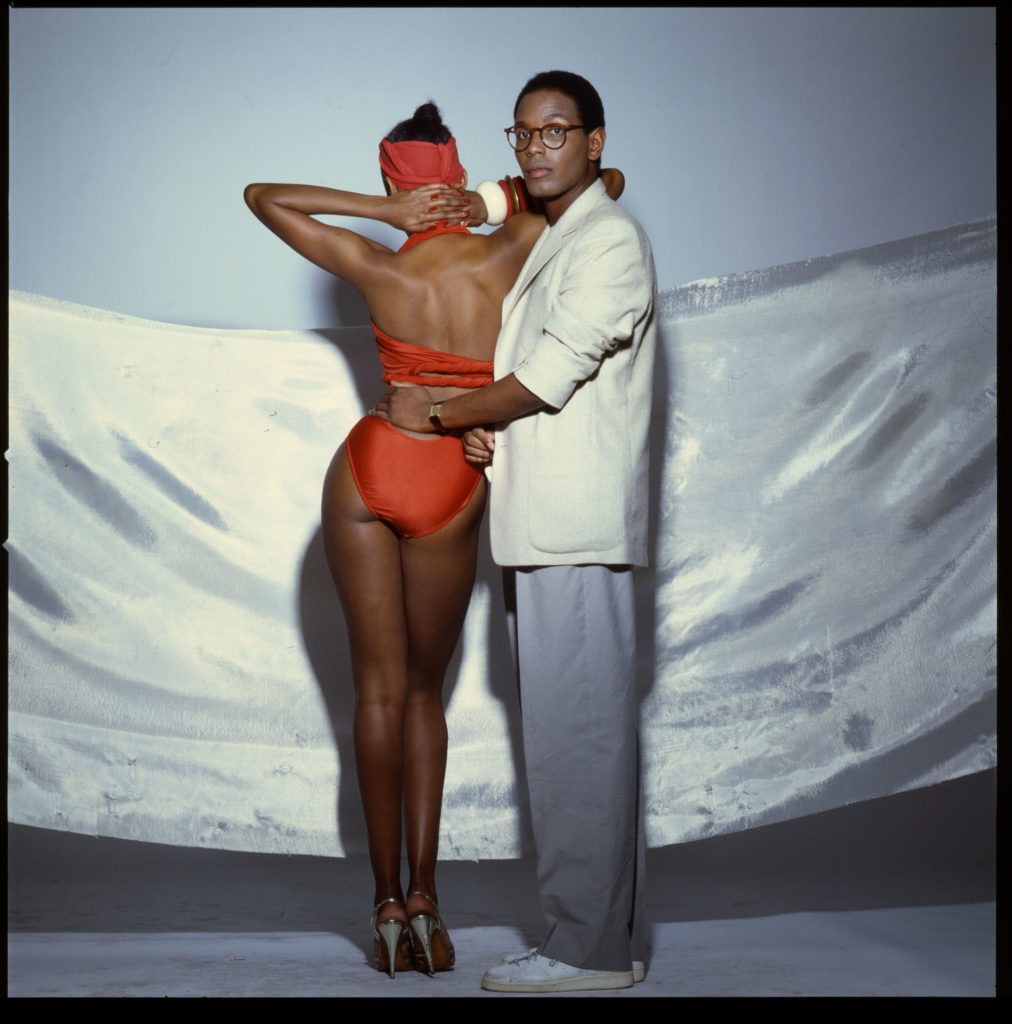

Willi Smith, ca. 1981

Courtesy Kim Steele

In 1978, when submitting his biography to the Coty awards, a respected fashion prize, the designer Willi Smith, of WilliWear, wrote, “My mother and grandmother were always ladies of style and still are. I guess they taught me that you didn’t have to be rich to look good. I believe that good clothes don’t have to be expensive.” In appearance, if not price point, WilliWear then was all that fashion is now: sporty, casual, gender-neutral, a mash-up of “high” and “low” (though Smith would never have categorized culture, or life, in those terms), and replete with bold graphic prints and fine-art collaborations. Name your contemporary fashion icon—Kim Jones, Virgil Abloh, Supreme’s James Jebbia—and Smith foreshadowed them. WilliWear was also about more than clothes, as most fashion brands are now; Smith talked of wanting to revolutionize marketing, and he worked across architecture, film, art, and performance, collaborating with the likes of Christo and Jeanne-Claude, SITE, Keith Haring, and Barbara Kruger. He even considered starting a magazine, mocking up a few copies in the mid-1980s, preempting the current role brands have embraced as publishers, speaking to broad audiences of viewers and followers, rather than simply dedicated pools of clients.

WilliWear: so far, so prophetic.

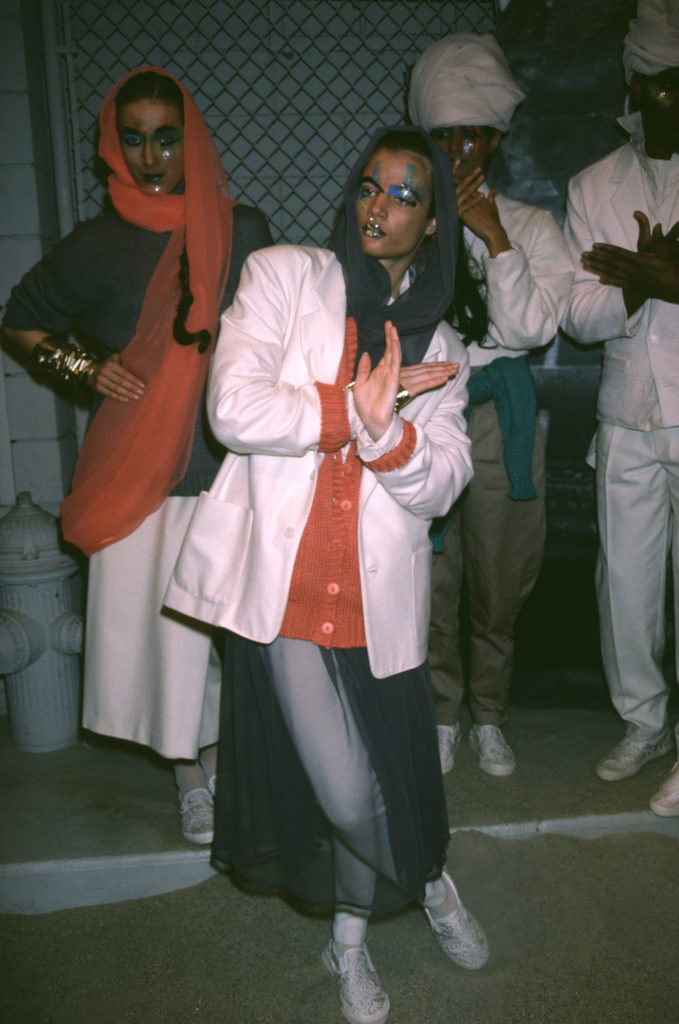

© the artist

Except, who remembers? Too few followers of fashion know the name Willi Smith, despite the fact that when Smith died at the age of thirty-nine in 1987, of complications related to AIDS, his brand was generating $25 million per year in revenue, and Smith was celebrated as a game-changer, a star, the nucleus of a dynamic group of Black designers who had dominated 1970s fashion. (If he had lived, “for sure Willi would have designed Barack Obama’s inaugural suit,” says Paper magazine founder Kim Hastreiter.) The amnesia is something Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York is keen to rectify with its exhibition and book Willi Smith: Street Couture.

A portrait of Smith featured in the book shot by Anthony Barboza (a member of the Kamoinge Workshop who dated Smith’s sister Toukie in the 1970s), shows the designer standing proud, regal, his face turned toward the camera, with one arm around his sister’s waist. She, clad in heels, red bikini and headwrap, has her back turned and her hip popped. She is the glamour queen; he, the calm support. The image suggests tenderness—Smith is portrayed as an ally, the man shoring up someone else’s confidence, or beauty; a reflection of his mission as a designer. The photographs of Smith’s work featured elsewhere, made by the likes of Steven Meisel and Max Vadukul, show a fresh take on fashion—one that was open, active. Models are seen laughing, being gorgeous, young in New York City. It is an optimistic vision.

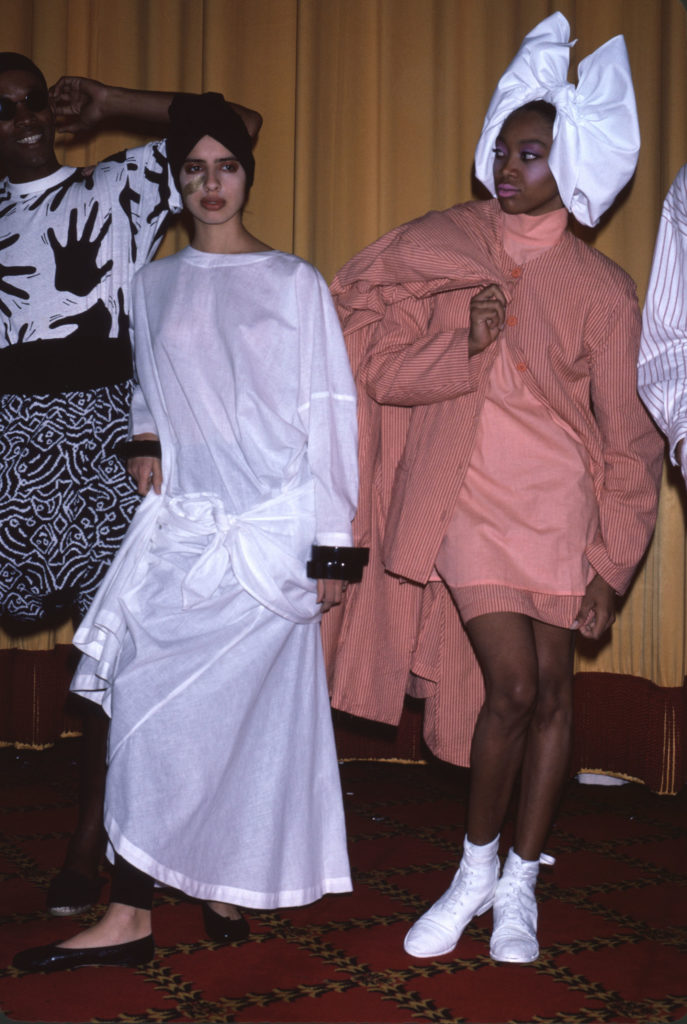

Courtesy the FIT Library Special Collections and College Archive

And yet, when style critics and curators talk of the game-changers of fashion history, those who pioneered the casual, the free, they mention Yves Saint Laurent or Coco Chanel, or American sportswear pioneers, such as Claire McCardell. Little credit or reverence goes Smith’s way. Naturally, it is easy to say he has been disregarded. But by whom? By the overwhelmingly white fashion establishment? By museums and archives? It is relevant, of course, that this is the very first book in the Smithsonian Institute’s history dedicated to a Black designer, a fact that surely goes some way in answering the question they have made central to their project: how could Smith be overlooked?

In one of the book’s many essays, “Vernaculars of Black and Queer Remembering,” Eric Darnell Pritchard references a lecture given by the poet and writer Melvin Dixon, who was dying of AIDS, at a conference for gay and lesbian writers in 1992. Dixon talked of the role the community—his friends, peers, and rivals—must play in ensuring their histories were not lost, in speaking up, in collecting, in preserving, lest others sweep their stories away. “Remember us,” he said. (He called his address “I’ll Be Somewhere Listening for My Name.”) So, as decades have passed, who has been calling out Smith’s name? It is his clients, his friends, his fans, his collaborators, who are doing the work of remembering. Street Couture makes heavy use of their testimony, relying less on official narratives—though there are quotes from Smith’s interviews with various fashion publications, and some essays from academics and researchers—but instead, on the authority, and memories, of those who worked alongside him, or have been inspired by his legacy, or who wore his clothes, modeled in his shows, those who loved him and were loved by him. “I’ve photographed people for fifty-five years, and very few stand out in my mind as having had that special aura about them,” Barboza writes in a tribute. “Alice Walker, James Baldwin, and Cesar Chavez had it, and so did Willi Smith.”

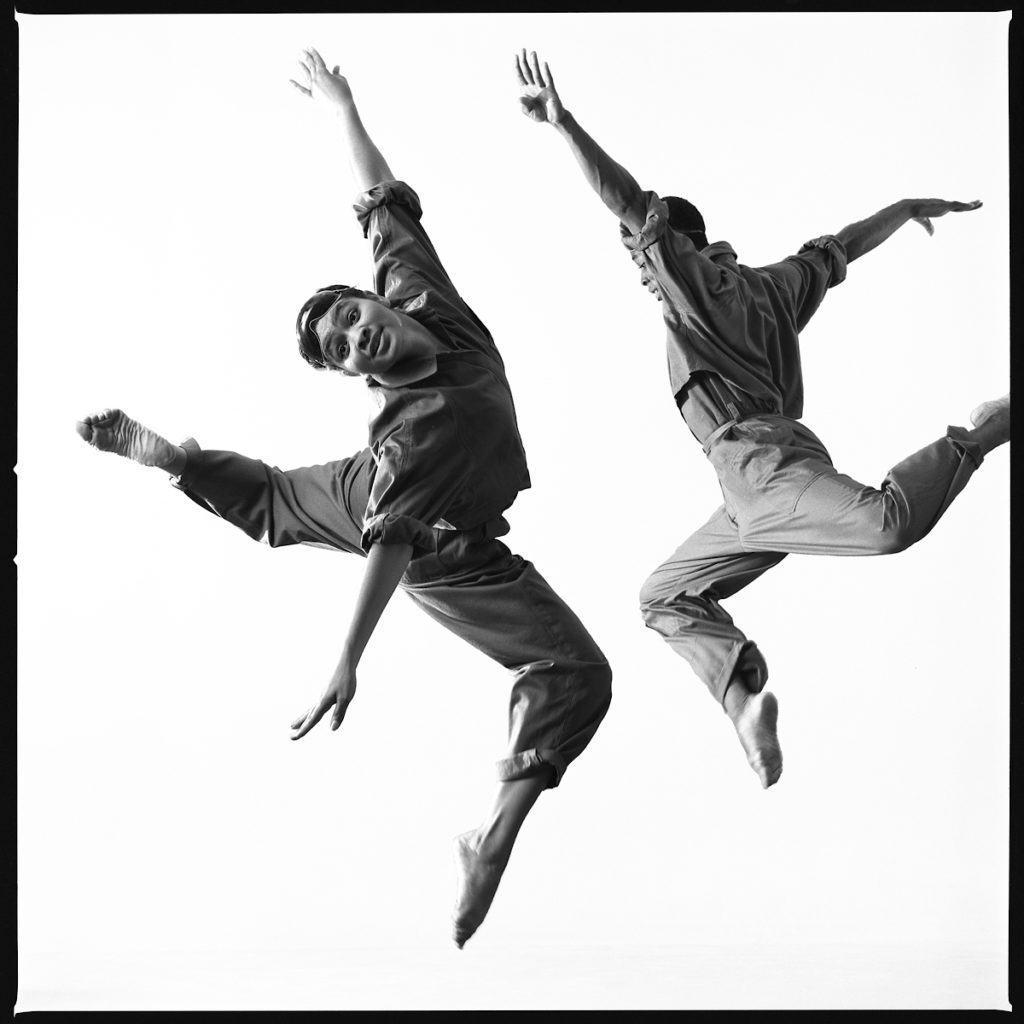

© Smithsonian Institution

Street Couture illustrates not only the breadth of Smith’s talents, but also the limits of how fashion has conventionally been archived, chronicled, and discussed, and the way existing hierarchies and habits of thinking hinder change, prevent due credit and celebration, and foster prejudice. Much damage is done by the process of categorization and definitions (a fact central in considering why Smith could be reluctant to being labeled a “Black designer”). The book considers the way Blackness is treated hegemonically, and the way the work of Black designers is often othered, grouped, or ghettoized. Indeed, WilliWear’s popularity led to it being separated away from fashion. It was worn and embraced by editors who simultaneously held it at arm’s length from “their” industry; as Bethann Hardison says in the book, “You used to see WilliWear everywhere. It was a brand that you would see everyone wearing on the street. That’s why editors started referring to it as streetwear.”

Kerby Jean-Raymond, of Pyer Moss, summarized this process in a 2016 interview (quoted in an essay in the book titled “To Be American”), when discussing how the output of Black designers is often automatically referred to as “streetwear”: “I just want to know what’s being called ‘street’—the clothes or me?” Such comments highlight the importance of questioning the limitations of institutional archives, and of challenging the standards laid out by gatekeeps who have, until now, cast themselves as authorities on the histories of design, fashion, and image-making. Whose boundaries should we accept? Whose categories are we working with? Whose acclaim matters?

Courtesy the FIT Library Special Collections and College Archive

In his commitment to crafting clothes for everyone, Smith was an activist as much as a designer. “I think he participated in politics through how he lived and what he made,” says the dancer Bill T. Jones when reflecting on his collaborations with Smith, including Secret Pastures and Made in New York (both 1984). The recent embracing of politics and social justice issues by numerous mainstream brands vindicates Smith’s approach; contemporary CEOs see now that to succeed in the long run, and in a time when social media has amplified diverse voices, one must be welcoming, one must listen. The fashion mood has shifted toward inclusivity rather than elitism, engagement (albeit often performative) rather than lofty distance. Of course, many brands adopt the language of Smith, while retaining the old business model, the old values. Smith, on the other hand, was all in. He was a savvy businessman, but opportunism or cynicism was not his bag. WilliWear was built with commitment and compassion. As Forest Young argues, “affordability today is not nearly as exquisite, or sincere.” Neither is fashion’s version of openness or diversity.

It’s tempting, because it’s easy, to say that Willi Smith’s work feels more relevant than ever, in part because of the current shifts in how we all get dressed—the supposed sweatpants revolution, the march of the cozy and relaxed—but also because of the widespread desires to spotlight Black makers, Black creatives, to use books and magazine pages and exhibition space to make up for past erasures. It’s tempting to do all this, because it’s obvious. But Willi Smith needs no hook, no justification to be interesting—he has always been relevant, his influence pulses through all that we have worn and consumed across the past five decades. He penetrated culture, infiltrated taste—“tainting the water,” as the artist Lisa Yuskavage puts it in the book. Yuskavage wore clothes made from WilliWear patterns as a youth, and her tribute is an unexpected addition, showing the breadth of Smith’s influences. Read it and then look closely, and you’ll notice that the clothing worn by the curvaceous figures in Yuskavage’s works often recalls WilliWear.

© the artist

“One of Willi Smith’s quotes was ‘style over status,’” Yuskavage writes. “Growing up, I didn’t have status, but through his patterns, I had the ability to make myself look and feel good. Some of my clothes were Willi Smith, but probably some were people copying him, and I’m interested in that too, as a form of influence.” It’s an answer to those who would say that because his name isn’t better known, Willi Smith’s influence must have been, in the end, limited. Instead, his impact is immeasurable. “An exhibition and book like this is trying to reconstruct that,” Yuskavage adds. “It’s like pulling a very complex marionette that’s got twisted strings, up from a lying-down position.”

Willi Smith: Street Couture was presented by Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, in 2020. The accompanying catalogue was copublished by Cooper Hewitt and Rizzoli Electa.