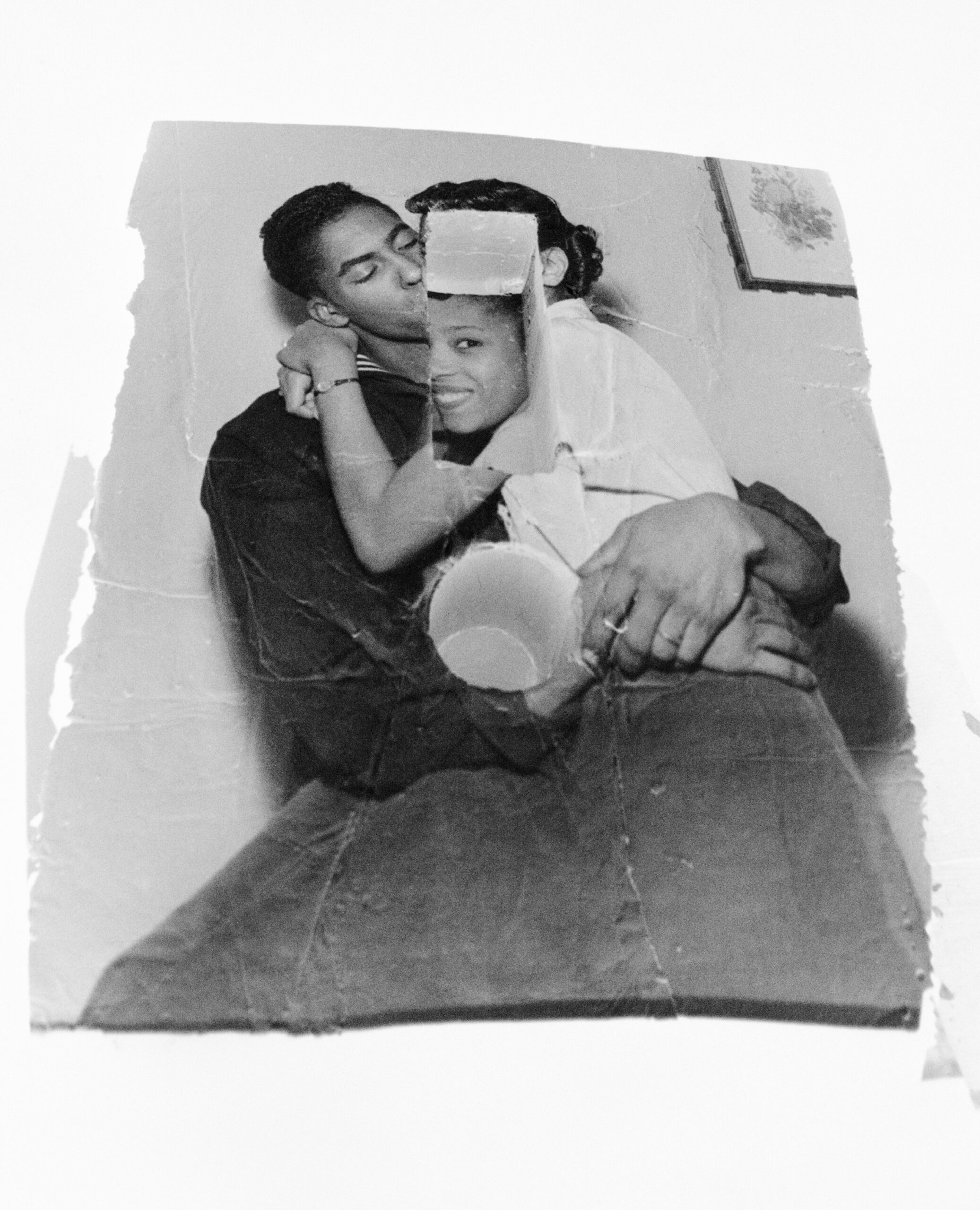

Darrel Ellis, The Kiss, 1990

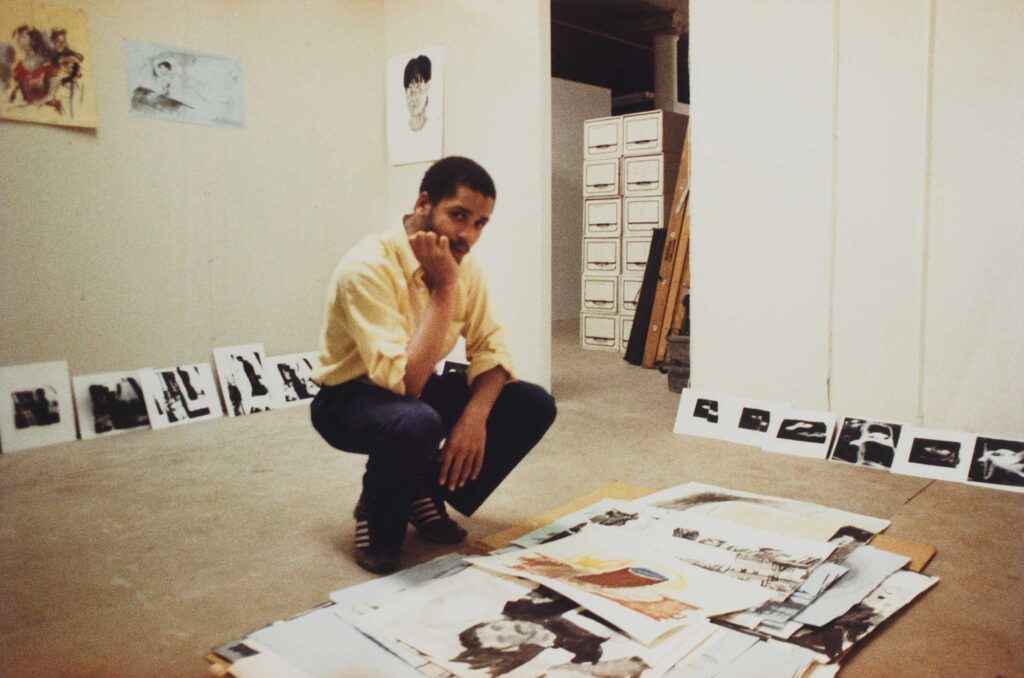

In 1979, Darrel Ellis and another artist named James Wentzy applied for a P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center studio residency, still a fledgling program at the time. Ellis had been out of high school for only three years, and he’d worked mostly in painting and illustration. But when the two got to the defunct school that had become P.S.1, in Long Island City, they built a makeshift darkroom where Wentzy taught Ellis to develop and print his own photographs. The furnace at P.S.1 would shut off at five o’clock each afternoon, but Ellis lived there for two years anyway, often wearing a coat and gloves inside. It was here that he and Wentzy devised the approach that would become Ellis’s calling card, of projecting negatives onto unevenly shaped sculptural forms to produce strange and illusory distortions.

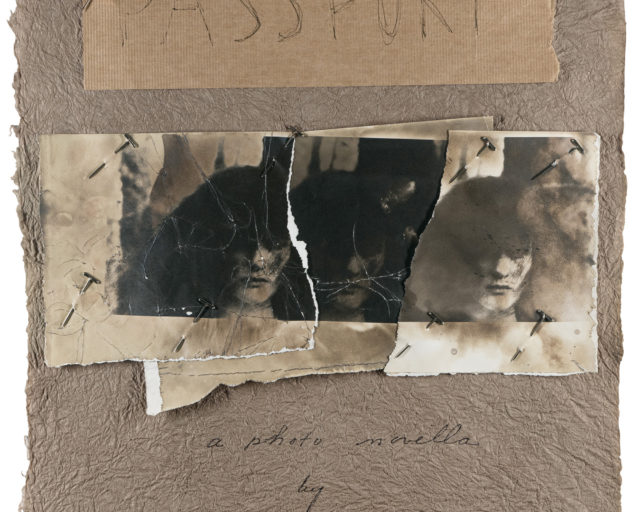

Courtesy the artist and Visual AIDS

As source material, Ellis used mostly family photographs taken by his father, who was tragically killed by police in a street altercation before Ellis was born. For Ellis, these placid pictures of family get-togethers represented a kind of prelapsarian peace he never knew, having grown up in the “Bronx is burning” era. After transforming the images into serial variations, he would reproduce them as paintings and watercolors, a process he referred to as deconstruction and reconstruction. These enigmatic sequences are the main attraction at the late artist’s first-ever museum retrospective, Darrel Ellis: Regeneration, a collaboration between the Baltimore Museum of Art, where it opened in 2022, and the Bronx Museum of the Arts, where it goes on view this spring.

The show has come together, in part, through the advocacy of Ellis’s friend Allen Frame, an artist and curator who began compiling the work when Ellis died, of AIDS-related causes, in 1992. Frame has been trying to secure Ellis’s legacy ever since. He curated a 1996 retrospective at the Manhattan space Art in General that traveled and received favorable reviews, but he later found it hard to get dealers and collectors interested. “The fact that he was using family photographs may have confused people at a time when that kind of imagery and photography was not so welcome,” Frame recently told me. “For most of the ’80s, the idea of photographing your friends and family was still not seen as legit in fine-art circles.”

Rediscovery isn’t as simple as it might seem, especially for gay artists such as Ellis who didn’t live to see their work celebrated.

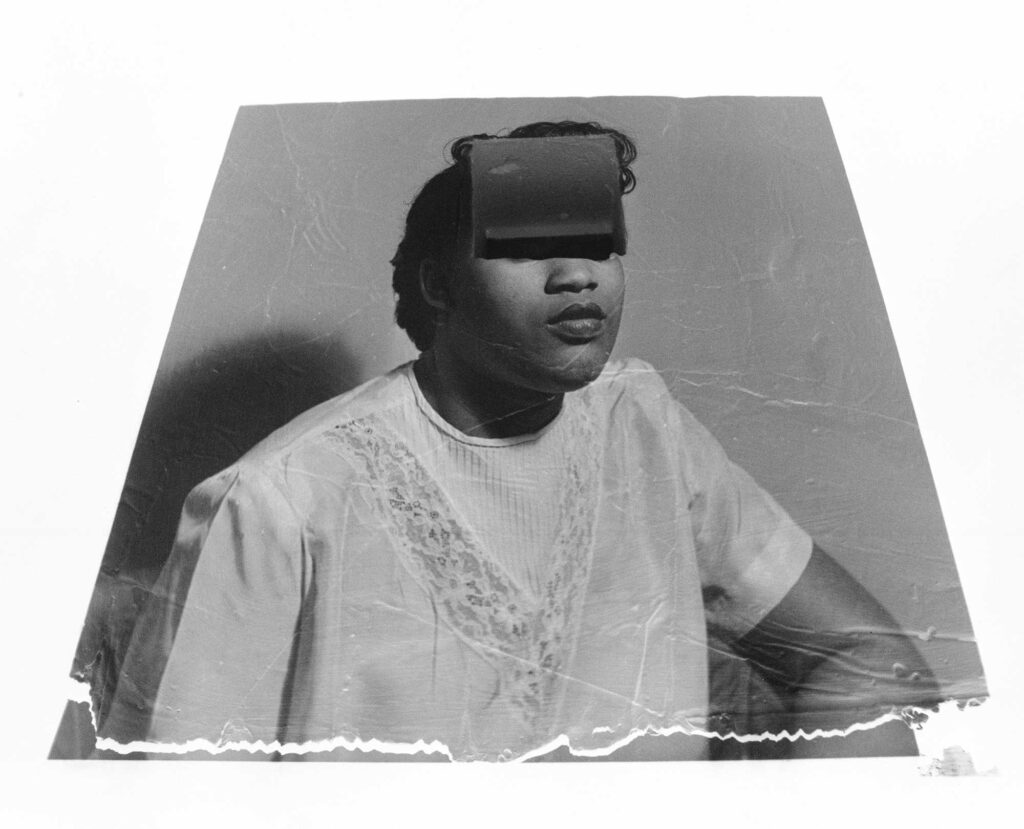

Then, around 2015, the curator Drew Sawyer happened upon one of Ellis’s photo-projection pieces, which the Museum of Modern Art had purchased for its New Photography 8 show in 1992, in MoMA’s collection. The uncanny image, Untitled (Mother) (1990), depicts the artist’s mother against a neutral photo-studio background, her eyes and forehead redacted by a vaguely ominous floating rectangle. Sawyer pitched a show to the art space OSMOS that went up in New York in 2019, kicking off a posthumous career revival for Ellis.

Courtesy Galerie Crone, Berlin and Vienna, and Darrel Ellis Estate, New York

At the Baltimore Museum of Art, the work was presented in the Cone Wing, which is typically reserved for nineteenth- and early twentieth-century European art: the period that most inspired Ellis. From frequent visits to hallowed Manhattan museums, he discovered that his artistic vision shared many concerns with turn-of-the-century painters such as Édouard Vuillard, who depicted the quiet magic of interior and domestic scenes.

After Ellis’s P.S.1 residency, he was accepted, in 1981, into the Whitney Independent Study Program—the only participant that year without a college degree—where he read poststructural theory, which got him thinking about the semiotics of photography and sculpture. Many of his photo-projection pieces are mind-bending object lessons about the thingness or materiality of the surface itself, especially such works from the late 1980s and early 1990s as The Kiss (1990).

For some black-and-white prints, Ellis projected a studio portrait of his mother and sister onto a surface of scooped-out squares and circles, causing their faces to be swallowed by light. He would create third-generation renderings of these second-generation images by painting the photograph of the projection on canvas. The result is a profound disorientation, as in the painting Untitled (Mother, Father, and Laure) (ca. 1990), which has the what-is-even-real effect of trompe l’oeil. Regeneration includes full displays of some of these works so viewers can see how Ellis’s ideas developed from one medium to the next.

“Reading his notebooks, it’s clear Ellis had a conceptual vision of how he wanted his work presented, which was to show it in all of its plurality,” says the exhibition’s cocurator Antonio Sergio Bessa. “We hope that by displaying some of the complete sequences, we can present the complexity of that vision.” It’s hard to know why the wider art world took so long to acknowledge that vision. Rediscovery isn’t as simple as it might seem, says Allen Frame, especially for gay artists such as Ellis who didn’t live to see their work celebrated. “In the aftermath of the AIDS pandemic, a lot of estates needed to be attended to,” he explains. “And not only that, but there was a lot of exhaustion and fatigue around it.” It may have taken thirty years, but the slight has finally been amended, and there’s no feeling like watching art history rewritten before your eyes.

Darrel Ellis: Regeneration is on view at the Bronx Museum of the Arts from May 24 through September 10, 2023.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live.”