William Gedney, from A Time of Youth: San Francisco 1966–1967 (2021)

In 1999, when I was an intern at the now-defunct photography and literature quarterly DoubleTake, housed at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, I was asked to proofread a survey of photographs by William Gedney. The revered but little-known artist had died a decade earlier. Since no books on his work had been published in his lifetime, What Was True: The Photographs of William Gedney, coedited by Margaret Sartor and Geoff Dyer, would be an introduction for most readers. It most certainly was for me. I was struck by the intimacy of Gedney’s photographs, the accidentally graceful human arrangements in his black-and-white frames: barefoot, stringy-haired girls loitering in a kitchen near a Kentucky mining camp in the 1960s; a young boy gripping the steering wheel of a stalled car; teenage boys and men gathered, shirtless, around the flipped-up hood of another broken-down car. Gedney’s pictures were both secretive and familiar. They spoke to the way I had felt watching grown-ups talk on my grandparents’ small mountain farm, when they thought us kids weren’t really paying attention. Gedney’s pictures let people reveal a hidden part of themselves in a way that other photographs I’d encountered of country people and poor people did not. He saw them with complicated beauty, without condescension. The people in his frames could, and did, desire and dream of worlds and existences beyond what was expected and assumed of them. In recognizing that quality, the photographer simultaneously revealed something of his own longing.

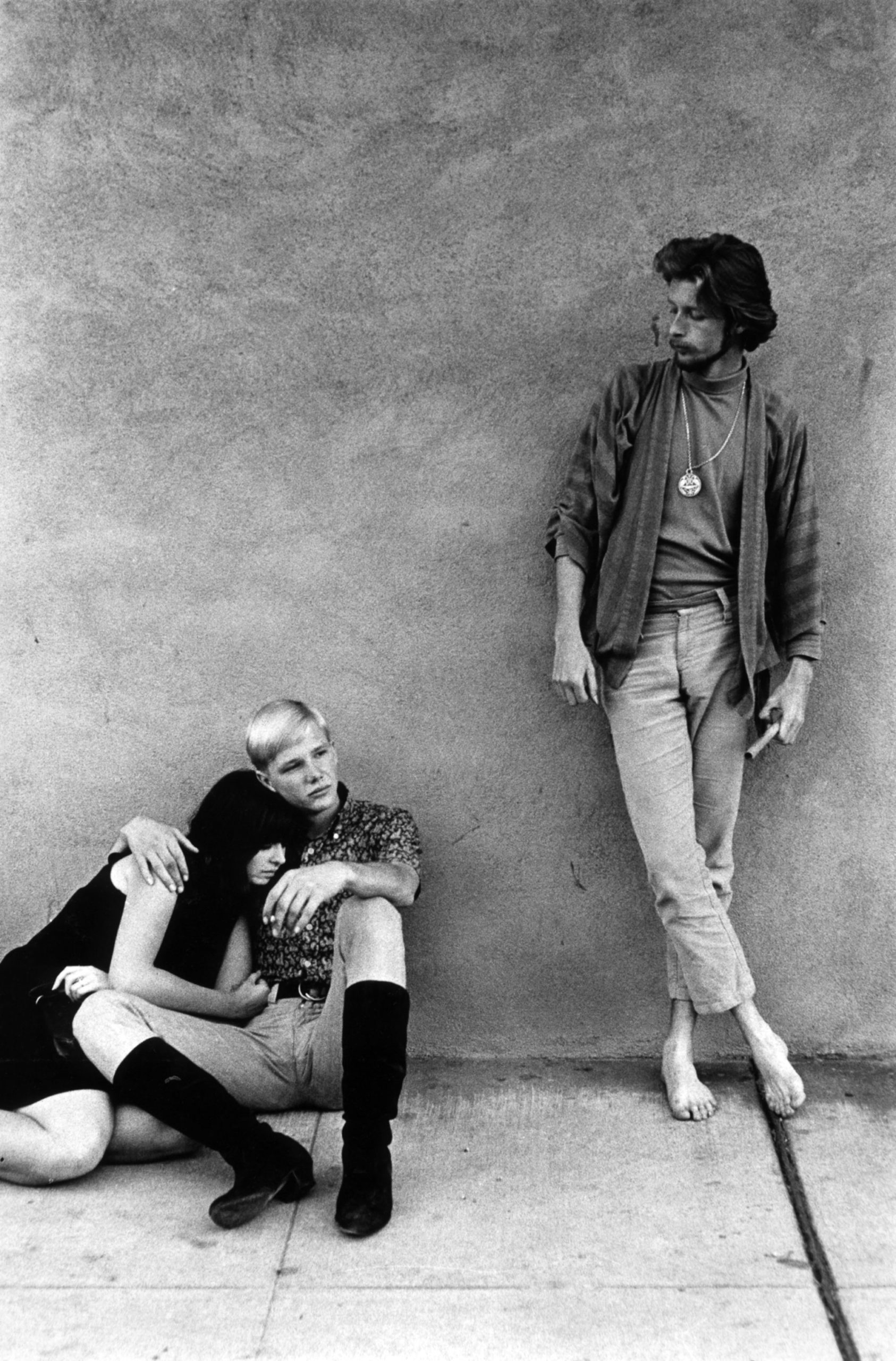

Gedney worked this way, whether photographing young seekers dropping out of life and making their way to San Francisco in the sixties, or people on the streets of India in the early seventies, or the regulars in a dingy, raucous bar in his Brooklyn neighborhood—which, many years later, would become mine too. Even his photographs of cars parked on empty streets and lonesome dark yards at night reflect human feeling. Just as palpable as the melancholy that pervades his pictures is a sense of camaraderie, a physical freedom among people nonetheless simultaneously harboring deep and private worries. The bonds between them showed in a dozen subtle, alluring ways, and Gedney captured them in multitudes, sometimes within a single frame.

William Gale Gedney was born in 1932 in Albany and grew up in rural upstate New York. At nineteen he enrolled at Pratt Institute of Art in Brooklyn, where he discovered what he would call “a natural feeling for photography.” In order to make his photographs on his own terms, Gedney lived frugally. For years, he made do in a cold-water flat in Brooklyn, not far from Pratt, filled with books and music and his steadily growing, meticulously organized archives. His degree was in graphic design and he picked up paying work at Time-Life Books and Condé Nast Publications; later, he taught at Pratt and Cooper Union, working jobs that were either temporary or that he’d quit when he saved enough money.

According to his friends, Gedney had a loud, bellowing laugh. To his friend and onetime lover writer Joseph Caldwell, Gedney jokingly claimed to be descended from “reindeer thieves.” About his photographs, though, he was absolutely serious. Maria Friedlander has written that Gedney had “often expressed his feeling that to be a truly committed artist one had to be free to pursue one’s work.” He was a “loner, very private,” she wrote. At least in certain circles, he kept his love life closely guarded, in a secret realm. Once, when she asked him if he wanted to get married, if he’d ever had a close girlfriend, he answered with that same bellowing laugh, one that Friedlander came to understand meant that she had “come upon a gate that he kept firmly closed.” In his 2019 memoir, In the Shadow of the Bridge, Caldwell recalls meeting Gedney in 1959 as they passed each other on the Brooklyn Bridge (the subject of a series Gedney was working on). They soon began an affair and exchanged apartment keys, but this relationship eventually dissolved as Gedney became consumed again with his art. When they reconnected again as friends in the mid-1980s, Gedney was visibly ill, covered in lesions from Kaposi’s sarcoma. He was living in the first and only house he owned, a fixer-upper on Staten Island where, under his care, a grape arbor, a cherry tree, and a vegetable garden flourished. He had also “semi-adopted” a German shepherd mix he named Mr. Dog. Caldwell, who had been volunteering support for patients through the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, would move in as caretaker. He was at Gedney’s side when he died at fifty-six years old.

In another world, one in which Gedney was allowed to live longer, or was exhibited more frequently, his name likely would be widely mentioned today alongside those who championed his work. This would include Walker Evans, who recommended Gedney for his Guggenheim grant in 1966; his friend Diane Arbus, who encouraged him to take over the teaching of her classes at Cooper Union; John Szarkowski, who gave him a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1968, which the curator described as a study of “people living precariously, under difficulty”; and Lee Friedlander, who with his wife, Maria, remained close to Gedney throughout his life. The Friedlanders were among those who helped arrange for the acquisition of Gedney’s archives by the special collections library at Duke University, including thousands of finished prints and seven handmade maquettes of the books Gedney never published in his lifetime.

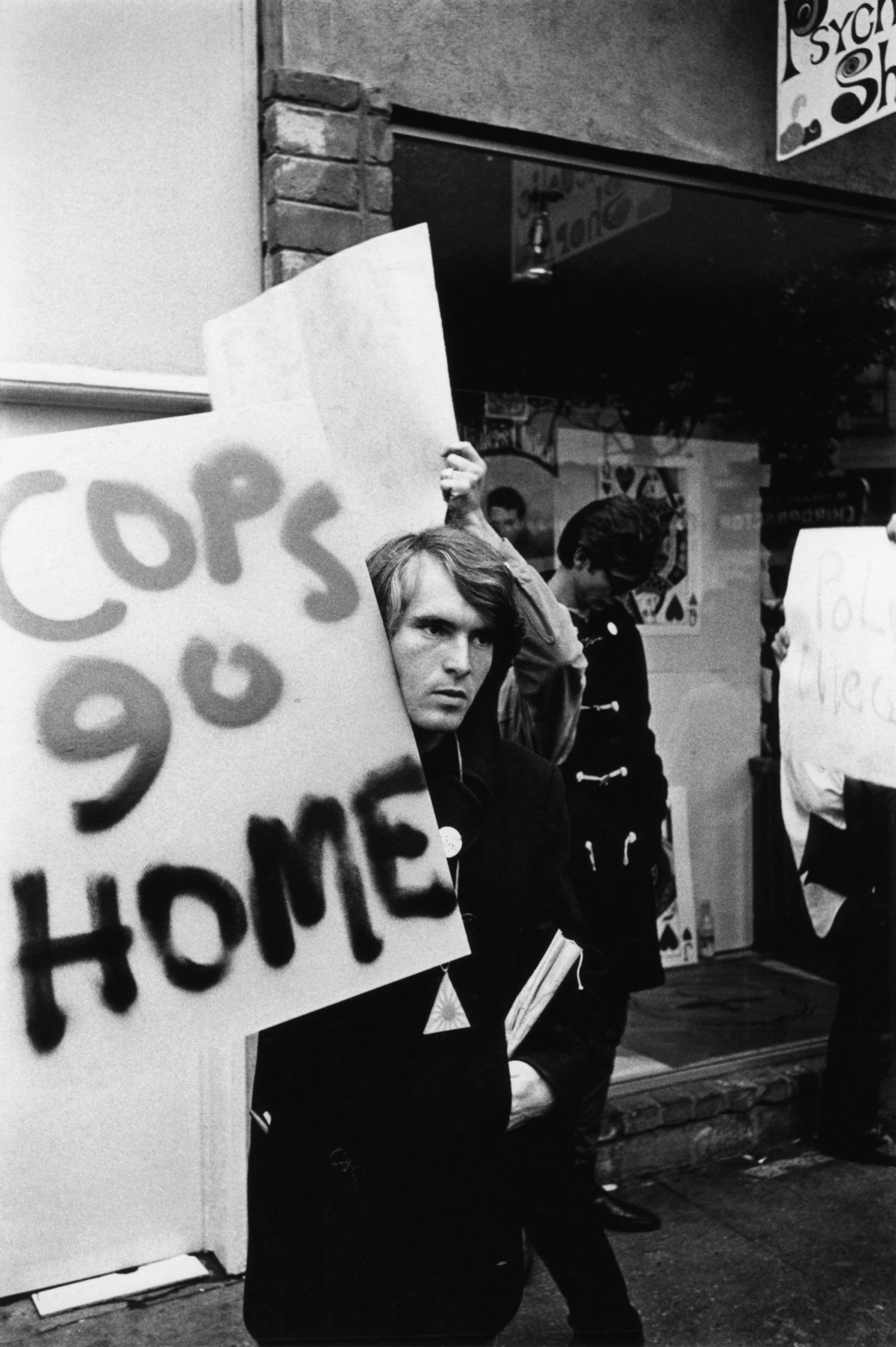

“They seem to be doing happy things sadly, or maybe they’re doing sad things happily.” This enigmatic remark by John Cage, a friend of the photographer, is one of only two brief texts that William Gedney included in an unpublished maquette that he titled A Time of Youth. Photographed in San Francisco over the course of ninety-nine days, from October 1966 to early 1967, the series is a witness to a time before a time—the preamble to the Summer of Love, transitory and searching, and refreshingly devoid of any grooviness or flower-power tropes that would later be implanted in collective memory. A Time of Youth: San Francisco 1966–1967, published in February fifty-some years since its inception, marks the first book devoted to a single, complete project by the photographer. About half the book is devoted to supplementary texts—pages from Gedney’s letters and journals, and in-depth essays by critic Philip Gefter and the book’s editor, Lisa McCarty. But at the core is Gedney’s maquette of eighty-nine images, revealing him as a prescient creator of the modern, lyrical photobook, which he saw as a unique literary genre. “I worked for the collective impression,” Gedney wrote in April 1969, “yet tried to make each of the individual pictures stand on their own.” He envisioned the photographs as elements in a story and sequenced them so that they progressed from morning to night—effectively collapsing his eighty-nine days into a semi-fictional twenty-four hours. In this way, he was as ahead of his time artistically as the young dropouts and hippies who had arrived on the cusp of the counterculture. A Time of Youth offers the first opportunity to see his long-form work close to the way he conceived of it—as a dramatic narrative formed almost entirely by the pictures.

“In another world, one in which Gedney was allowed to live longer, or was exhibited more frequently, his name likely would be widely mentioned today alongside those who championed his work.”

McCarty writes that, although she added essays and contextual materials, she otherwise tried to hew to the specifications in Gedney’s notes, including the book’s sequence. She enlarged the dimensions slightly (the book measures nine by nine inches; Gedney desired eight by eight). Compared to his luminous Kentucky photographs, the San Francisco work tends to be darker in emotional tenor and denser in tonality, with semi-obscured figures and downturned, daydreaming faces. A Time of Youth feels kindred to “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” Joan Didion’s landmark essay depicting the grimmer, disillusioned side of Haight-Ashbury, as if Gedney and Didion had stepped inside the same living rooms. Both were a generation older than the young people they photographed and wrote about (Gedney was born two years before Didion). Both must have had a way of making themselves invisible in these spaces. A fragment from “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” could well be transposed as a Gedney caption:

It is three o’clock and Deadeye is in bed. Somebody else is asleep on the living room couch and a girl is sleeping on the floor beneath a poster of Allen Ginsberg, and there are a couple of girls in pajamas making instant coffee. One of the girls introduces me to the friend on the couch, who extends one arm but does not get up because he is naked.

But Gedney’s pictures didn’t require words (nor did Didion’s essay require pictures). In his notebooks, Gedney characterized A Time of Youth as “an attempt at visual literature, modeled after the novel form.” The narrative of the book unfolds entirely through the photographs, with recurring characters that evolve and are changed, even if their transformations are not outwardly, explicitly revealed.

Organized in seven movements, the book’s structure is also inherently musical, influenced by Gedney’s avid appreciation for twentieth-century composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen, Roger Sessions, and especially Charles Ives. Music becomes a motif: the recurring appearance of the guitar in the first movement, a wooden recorder in the next. We wake up inside a crowded communal room, with two shadowy, androgynous-looking people, lying on the floor in a rumpled blanket, one cradling the other’s face as he reaches idly for a guitar propped in the corner.

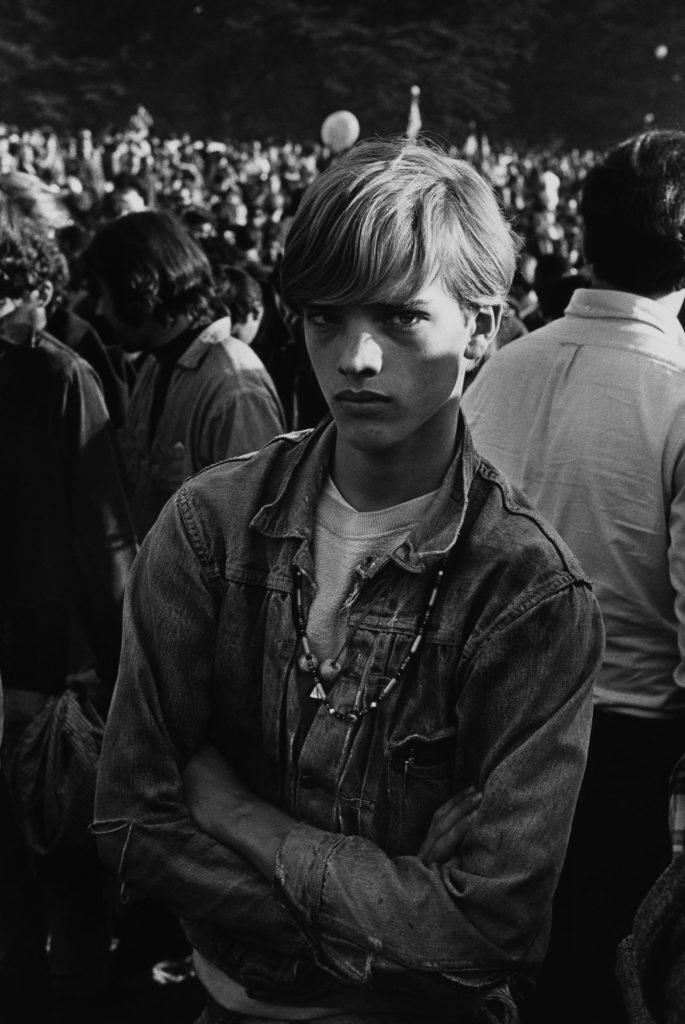

“Youth restlessly lounging over parked cars, in doorways, against store windows, garbage cans, parking meters, trees, each other,” Gedney writes in his notebook. We are drawn to the infinite and unconscious arrangements of bodies, curled up against each other but gazing outward and away; bodies sleeping under tables; hands snaking around waists, kissing, hugging, hands clasping hands; or of clusters of bodies, drinking tea on mattresses in front of portraits of Jean Harlow and Marlon Brando, or playing guitar in stairwells and slouching on stoops. Many of the pictures were made inside a communal house called “the Pad,” near the Grateful Dead’s house. And the concluding sequence of the book takes place at a Human Be-In at Golden Gate Park. Twenty thousand people showed up but Gedney sought out individuals: a couple lying on the grass in deep conversation, a boy draped in beads staring defiantly at the camera, and another, eyes downcast, holding himself tightly close. In the final image, a lone man in the foreground hunches his shoulders, looking on as blurred figures wander off into the fog. With his hair cut short and in a dress shirt, the observer is an outsider in this world, a proxy for the photographer himself.

© William Gedney, William Gedney Photographs and Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

In the last months of Gedney’s life, Joseph Caldwell recalls in his memoir, he only occasionally mentioned the books that came close to publication but were never realized—a deluxe edition of his India work, a book of his series of portraits of composers. “Could he have become so discouraged by these disappointments that he suffered a photographer’s version of writer’s block?” Caldwell writes. And yet: “Even though he had no instinct for self-promotion, he did have—I don’t doubt—a sure sense of his own worth and the artistic value of the work he’d done.”

The overdue arrival of this Gedney book is also a testament to the artist’s faith in the longevity of his work and the degree of sacrifice he undertook to protect it. Often, I walk past Gedney’s old apartment in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, and look up at the window from which he made a daily series of the same photograph of the view outside: the elevated train that ran along Myrtle Avenue in those years, the shops and street below, and I think of the long, cold winters he spent working there, of his pictures of the street blanketed in snow.

A Time of Youth: San Francisco 1966–1967 was published by Duke University Press in 2021.