Wolfgang Tillmans, Shaker rainbow, 1998

How should we live if life is finite? What is our responsibility to our families, our communities, and our environment? How can we practice a secular faith beyond the constraints of institutionalized religion? In his latest book, This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom (2019), the renowned professor of comparative literature and humanities Martin Hägglund grapples with notions of faith and freedom spanning the work of writers, theorists, and activists from Martin Luther King Jr. to Karl Ove Knausgaard. The meaning of life, he argues, is not found in devotion to eternal existence but instead in caring for what we know will be lost. “Secular faith will always be precarious,” Hägglund writes, “but in its fragility it opens the possibility of our spiritual freedom.”

For Aperture’s “Spirituality” issue, guest editor Wolfgang Tillmans spoke with Hägglund about his own connections to spiritual awareness and the responsibility of photography amid a “terror of images” in our online networks. Long interested in the concept of fragility, Tillmans poses questions about the anxieties of time and the need for solidarity under global capitalism. If an artist can make meaningful connections between people, does photography foster respect for the world?

Wolfgang Tillmans: When I was asked by the editors of Aperture to guest edit an issue, I immediately knew that it should be spirituality because I strongly sense that the political shifts in Western society that have surfaced in the last ten years stem from—besides actual growing inequality—a lack of meaning in the capitalist world. This lack is happily filled with substitutes like religion, nation, sport, and consumption, plus, of course, family values. But this lack of meaning is expressed a great deal in a quest for spirituality, which, I have observed, is primarily a self-bettering one. It is about feeling better.

And I wondered about the role of photography in that quest. Ten years or so ago, there were articles about having discovered the God gene, a genetic tendency for religious feelings. If true, I would say I have that gene. I’ve always felt a closeness to a spiritual awareness. But I’ve found also the contradictions in that awareness, and the role photography plays in it.

Martin Hägglund: One thing I’m concerned with in my book This Life is how we should diagnose that sense of something lacking in our society. And a very dominant narrative, which is usually associated with the idea of disenchantment, is that we have this sense of lack because we have lost something we once had: the spirituality that we supposedly need to get back to. In contrast to that perspective, I’m trying to show that if something is lacking, it’s not because we have lost something that we should retrieve. It’s rather because we haven’t fully actualized our freedom, our spiritual freedom, both individually and collectively. So I want to focus on understanding this sense of alienation and lack that many people have, not in terms of the loss of a religious past, but in terms of us not yet having achieved a secular, free future.

Tillmans: What is interesting in your proposal is the lack of anger at being finite.

Hägglund: Right.

Tillmans: The existentialists had to somehow put in the concept of revolt, or the “even though”—even though it’s pointless, we are still doing it to make peace with the human condition. But that anger is completely lacking from your book and thinking. Which is very disarming. Have you been criticized for that?

Hägglund: Actually, I think it has contributed in deep ways to the positive response to the book. I want to make clear, though, that I acknowledge and underline that it is painful and difficult to be finite. But I think that pain and difficulty are also intrinsic to anything that can matter, to anything that can be important. For the same reason, even though I am not angry at us being finite, the book is very concerned with how we can lead our finite lives in a better way. So This Life certainly wants to be transformative and revolutionary in that sense. But instead of aiming to overcome the condition

of finitude per se, I am concerned with how we can flourish more deeply in our finite lives and do justice to our vulnerability and our interdependence.

Tillmans: I feel fundamentally that we want connection, and that really is the most meaningful when it means connection to other people. But how do you explain this focus on being one, on being connected to nature, to the inner self, to crystal energy, and so on? This self-optimizing spirituality that is focused not on what we do together.

Hägglund: Precisely because of the antagonistic form of social life under capitalism, people tend to think of spiritual fulfillment in terms of turning away from our interdependence—precisely because that interdependence is so constraining and painful under capitalism. But the desire for social connection as expressed in the alienated form that you are talking about could be turned toward more social, emancipatory ends, which would recognize what I’m calling “a secular impulse to cultivate our shared life”—rather than trying to escape our shared life into some sort of fantasy of self-fulfillment.

Tillmans: As a photographer, I have been observing for a long time a dichotomy in myself between aiming to live in the moment and the very nature of photography as materializing moments. This life lived in full awareness that there’s nothing beyond the here and now leaves behind a trail of images and physical prints. Have you ever thought about this photographer’s dilemma?

Hägglund: It has actually been an abiding concern for me. There’s a connection to an important distinction I make in the book between two things that we tend to conflate—an aspiration to what I call “living on” versus an aspiration for eternity. To live on is not to transcend finitude, but to prolong a finite life. What’s interesting about photography is that it tries both to seize a moment that is fragile and fleeting, and to preserve it or trace it in some way. Not to make it eternal, but so that it can live on for the future and be taken up again. That whole desire is animated from within by the fleeting sense of the moment as you try to capture it. But it’s not about eternity—it’s about connecting across time and space.

Tillmans: Yes.

Hägglund: There is a tendency to think of our attempts to counteract the passage of time, or preserve memories (whether through photography or other means), as testifying to our desire for eternity or timelessness. But I think it actually testifies to our desire to live on and keep the mortal alive, which is quite different from making it eternal. Photography is a particular manifestation of that desire.

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art and courtesy Art Resource, New York

Tillmans: People always think that this megaphotography proliferation happened in the last ten years. But for me, there was already a crazy increase in the late 1990s with small point-and-shoot cameras. When I looked at what people did, I realized that they were not really interested in the pictures they were taking; instead, they were interested in being seen taking photographs. So they wanted to be seen as doing something about the situation, in response to the situation they were in, as opposed to being one with the group or the situation.

Hägglund: And how do you see that in relation to the problem of social connection that you’re thinking about? Do you see it merely as an alienated expression of the desire for connection, or is there some truth in it?

Tillmans: You’ve put the finger in a sore spot, because of course, by observing that in others, I wholeheartedly exempted myself from it.

Hägglund: Yes.

Tillmans: I am, of course, taking pictures only for my own purpose and for no reasons of empowerment or disconnection. [Laughs]

Hägglund: What role do you see for photography in your own work with regard to negotiating the problem of social connection?

Tillmans: One could stop the question quickly with the question, Why take a photograph of the sky or a tree if we have the option to simply lie in the grass and look at them and enjoy the nature surrounding us? But that doesn’t do justice to the very nature of art (and photography included). Art is not, and photography is not, just a depiction of a kind of reality; they are also a new reality in their very existence. They not only speak about something, but are actual things, objects that do something new entirely and something that the depicted subjects don’t do on their own. So there is an act of transformation happening, which is not just recording. I don’t believe that photography is just an act of appropriation.

I’ve always felt a closeness to a spiritual awareness. But I’ve found also the contradictions in that awareness, and the role photography plays in it.

Hägglund: Right. It’s also transformation.

Tillmans: Language, I find, often prefers yeses and nos, black and white, and I find that photography is both. It’s not an act of appropriation, yet we are taking pictures—there is this act of somehow feeling empowered by doing it, even if it’s very benign and mild.

Hägglund: Even though, as you rightly point out, photography is not simply representational and it’s a transformative practice, is there still a question of fidelity to the object? A question of fidelity and keeping faith with what you’re depicting?

Tillmans: There’s definitely no rule to that. For me, authenticity speaks primarily about the authenticity of the idea behind the photograph, because it can never be faithful to the original, because it’s actual ink on paper or dyes on paper. I find there is a direct correlation between how genuinely interested I am in what I’m looking at and how faithful the photograph is—between how genuine the photograph is and how likely it is that I care about that picture. Meaning, when I am really interested in what I am looking at, it usually yields a good result, whereas when I am only taking a picture because I want to make more of the same subject, for example, or because I want to please somebody, then that intention is what is written into the photograph, and it’s the first thing one sees. It’s the same with if you want to take a picture in order to take control of the situation, then that is also what is visible. But when you have a humble approach, that humility, or that genuine interest in the subject, is somehow what can be felt, what is visible.

Hägglund: Do you see it as a task of the art of photography, and yours in particular, to create the form of social connection that you have been talking about?

Tillmans: I see photography as nothing else but an expression of how I look at the world, which sounds like a very banal truism, but how we look at things is actually all that matters, and it’s in the how. If it is nonjudgmental, if it is from above, from below. I hope for connection with others who recognize that similar approach to the world in the texture or the mood or the feel of a photograph. They might sense, Oh, I know how that feels. Or, I know how that smells. That’s the only connection I can really go by, and that is a moment of feeling less lonely in the world. We can ask: Does photography foster respect for the world?

Hägglund: One of the things that photography does is disclose someone’s take on the world, and thereby our responsibility—our answerability—for the stands that we take. Insofar as photography fosters respect for the world, I think it has to do with recalling us to our responsibility for the stands we take.

Tillmans: Going against the introspective sense of spirituality, I chose to consider the theme of the issue with the word solidarity—“Spirituality Is Solidarity.” How do you define the word solidarity?

Hägglund: I argue emphatically that spiritual life should be understood in social and material terms rather than in contemplative or supernatural terms. I think that immediately links it to solidarity.

Tillmans: Now we are experiencing what I call “the terror of images.” With social media, et cetera, everybody is engaged in the act of photographing their lives and making these objects. They are no longer prints but mainly data banks. I feel like it’s this materialism that is disturbing the peace of mind of people. This constant torrent of turning moments into pictures is creating ever more matter, even though they are only data bits, as they are usually not printed. But what is this closed loop, this short circuit doing?

Hägglund: There would be one type of approach that would say that the problem with the onslaught of images and the obsession with Instagram is that they deprive us of our peace of mind. Then one thinks about spirituality in terms of contemplative peace or something like that. In contrast, I define spiritual freedom in terms of our ability to own the question of what we ought to do with our time, which is compromised if we are just absorbed by an onslaught of images.

Tillmans: It takes so much time to look at them.

Hägglund: That kind of absorption tends to make you forget that there’s always a question of what you ought to do, and what your priorities are, and what really matters. That’s where art and photography can play a counteracting role—precisely by art not being absorbing in the same way that social media is absorbing.

Tillmans: This correlation between freedom and the time that we are able to spend, which you make in your book, is so striking and goes back, as you explain, to Marx and others. I was really struck, like a bolt, in the London Underground, in 2005, seeing this huge billboard from IKEA, which I sent an image of to you yesterday.

Hägglund: Oh, yes.

Tillmans: It reads, “Welcome to life outside work,” and it shows a couple looking at books, and the signature says, “If your kitchen costs less you can work less.” That’s so fantastic, to be in London in that decade, which was already a hyper- hyper-work-driven climate, and which, of course, is even more so today. But this assumption that if you have a little bit more money, you can actually spend less time working, as if there is such an elasticity in today’s world, was fabulously naive, utopian. It could only come from a Swedish company.

Hägglund: We tend to associate freedom with freedom from work, or leisure time, in the simple sense. Precisely because so much of the actual work we have to do is not meaningful, and we can’t see the purpose and the point of it. The emancipatory point, however, is not to be free from work, but to be able to be engaged in, and committed to, activities and work that are meaningful in themselves. Work in which you can affirm and avow the point and the purpose of what you are doing. So I think it’s a very reductive and misleading idea of freedom and liberation that it would just be freedom from work, and just be leisure. But that’s also a symptom of how labor is organized under capitalism.

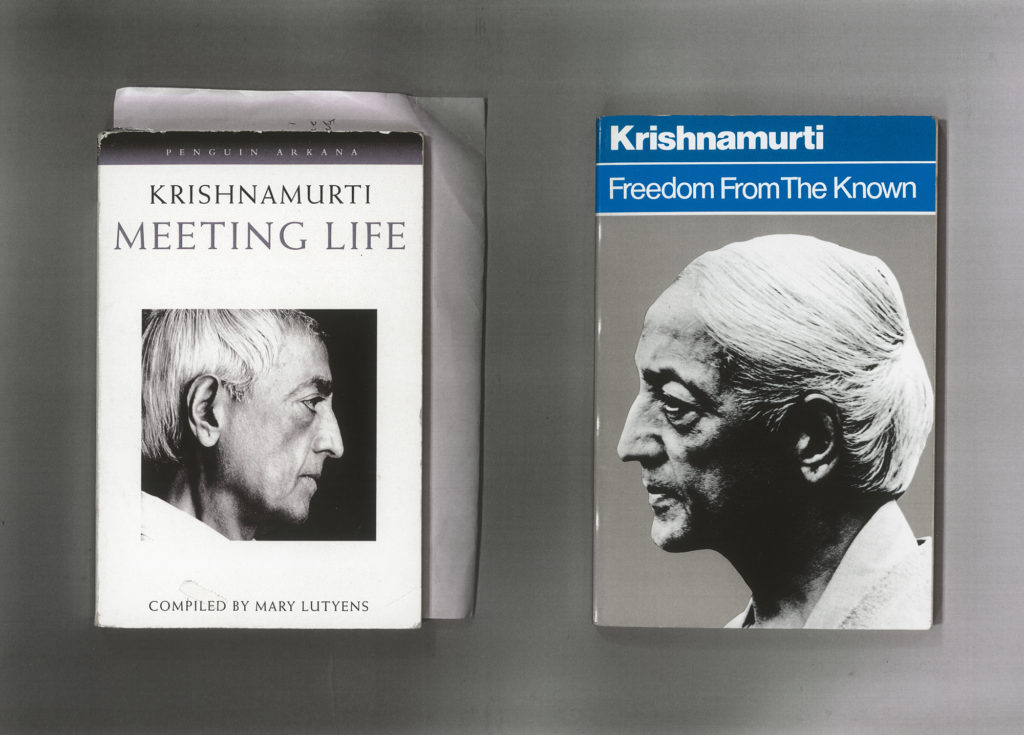

Tillmans: Yes. Have you read, or are you familiar with, Jiddu Krishnamurti? He has been influential at times in my life. He is striking in his complete and utter rejection of religion and religious authority, but he has written dozens and dozens of books on spiritual thought and thinking and philosophy. There’s one line that says: “How am I to be rid of every image I have gathered so that the mind is completely fresh and young, so that it can observe anew the whole movement of life?”

Hägglund: I think one needs to be careful here, because there’s one notion of the movement of life that is vitalistic and in my view deeply problematic: a notion of life as just this flowing force that you can tap into, and that would transcend the fragility and materiality of living beings. That’s a very misleading speculative temptation: to make the idea of life so dynamic that we end up denying the finitude of the material support on which any form of life depends.

All works by Tillmans courtesy David Zwirner, New York/ Hong Kong; Maureen Paley, London; and Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin

Tillmans: Another thing, of course, is that the idealized images often deny the fragility of life. And pictures in capitalism and also commercial pop culture are all idealized and are almost designed to deny the fragility. They are sort of feeding into this terror of images that leaves people alone with these feelings of their own fragility, as if that is something wrong, as opposed to seeing the strength in being in touch with your fragility.

As I wrote to you in my recent letter, I have had this close connection to the word fragile since I was a teenager in the 1980s, when I used it as my nom d’artist for my fledgling artistic endeavors.

Hägglund: I was fascinated by that detail.

Tillmans: In recent years, I have resurrected the word in my work, using it as the name for my record label and band project. I noticed the word, in general, coming up so much more in discourse and language and conversation. It’s striking. And again, it is a central word in your book.

Why do you think we have a greater sense of fragility today than fifteen years ago?

Hägglund: Well, one very obvious reason has to do with the climate crisis, and the fragility of the conditions of life itself being more and more manifest to us. Alongside, of course, an increased sense of social precarity. Even though we’re more fragile, our fragility is also unevenly allocated, depending on social and historical circumstances. The way in which we are finite and fragile differs so much, depending on the conditions we find ourselves in, and recognizing that is part of being committed to transforming those social conditions.

Courtesy the artist

Tillmans: Where it all matters is what we actually do about it together.

Hägglund: Exactly.

Tillmans: I wanted to keep the focus close to photography, and what it does to people, what it answers and leaves unanswered in people. Do you have maybe one last thought on that? I feel there’s a lot of passion with photography. It’s very central in our world now. But it’s also never really talked about, because there is a lack of language. Even among art historians, often there is a lack of language about photography. Especially among everyday people, it’s very limited. And at the same time, increasingly pictures are being used as words. They are somewhat substituting for words, emojis are becoming words, but there is no language about them that people are engaged in.

Hägglund: Photography, in a way, becomes a sort of focal point for all the anxieties about truth and representation that we’re facing. Because, of course, photography historically has been seen as a truth-bearer, and yet people are now so intensely aware of how easily manipulated photography is. So it becomes a focal point for anxieties concerning the language of truth, and we need to own up to that anxiety.

Tillmans: In that way, let’s hope we keep that language more nuanced.

Hägglund: Yes. Absolutely.

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, 237, “Spirituality,” under the title “Spirituality Is Solidarity.”