When Women Get Involved

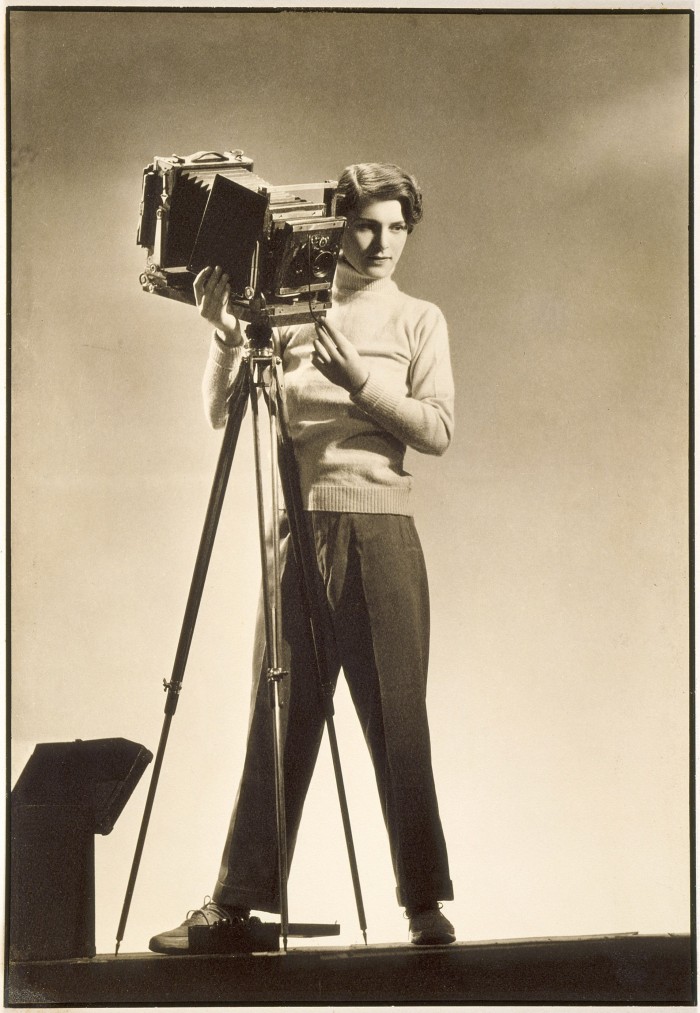

Margaret Bourke-White, Self-portrait with camera, ca. 1933 © Digital Image Museum Associates/LACMA/Art Resource NY/Scala, Florence

This winter, a dual exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay and Musée de l’Orangerie titled Qui a peur des femmes photographes? 1839–1945 presents a survey meant to highlight the long history of contributions to photography by women practitioners and artists. Throughout this expansive, multi-venue project, the visitor is invited to take a critical approach to the history of photography and to ponder the value of gender-specific exhibitions. In a mechanical visual medium that seems more resistant to distinctly male or female touches than other arts, the diverse selection of photographs here constantly reminds us to consider who was behind the camera and why. By choosing to exhibit a very large sample of lesser-known women photographers, Qui a peur des femmes photographes? aspires to enrich or even rewrite photographic history.

Barbara Morgan, We are three women – We are three million women, 1938 © Münchner Stadtmuseum, Sammlung Fotografie

The first of the exhibition’s two parts, hosted by Musée de l’Orangerie, covers the years from 1839, marking the French patent on photography, to 1919. The second, at Musée d’Orsay, is bookended by the two world wars. As for this division, the end of World War I, of course, brought about social and political changes, but many stylistic patterns continued from the previous era. The chronological set-up seeks to narrate a story of both stylistic experimentations, exploring the possibilities and limits of photographic processes and social developments by and of women photographers, but sometimes lacks context about the individual careers of those who are not as famous as figures such as Julia Margaret Cameron, Gertrude Käsebier, or Dora Maar. Take Madame Yevonde and her path breaking work in color photography, or the pioneering travel photography by Helen Messinger Murdoch. Monographic exhibitions on these artists would grant their place in the pantheon of photographers.

Christina Broom, Young Suffragettes advertising the Women’s Exhibition, 1909 © Museum of London

But what is distinctly female about the works in this exhibition? For me, as a male viewer, Lee Miller’s early-1930s anti-voyeuristic image, Severed Breast from Radical Surgery in a Place Sitting, an image of an amputated breast on a plate, haunts me more than any other image on view. It made me realize that the title of the exhibition is ill-chosen: it should not have been Who is afraid of female photographers? but What Are Men Afraid to Photograph? Whether this might be explained by the impossibility for men to separate the breast from its maternal or sexual functions is open to discussion: Miller, in any case, shows a relationship to the breast that transcends these categories. In Miller’s transgressive audacity, something decidedly feminine can be found.

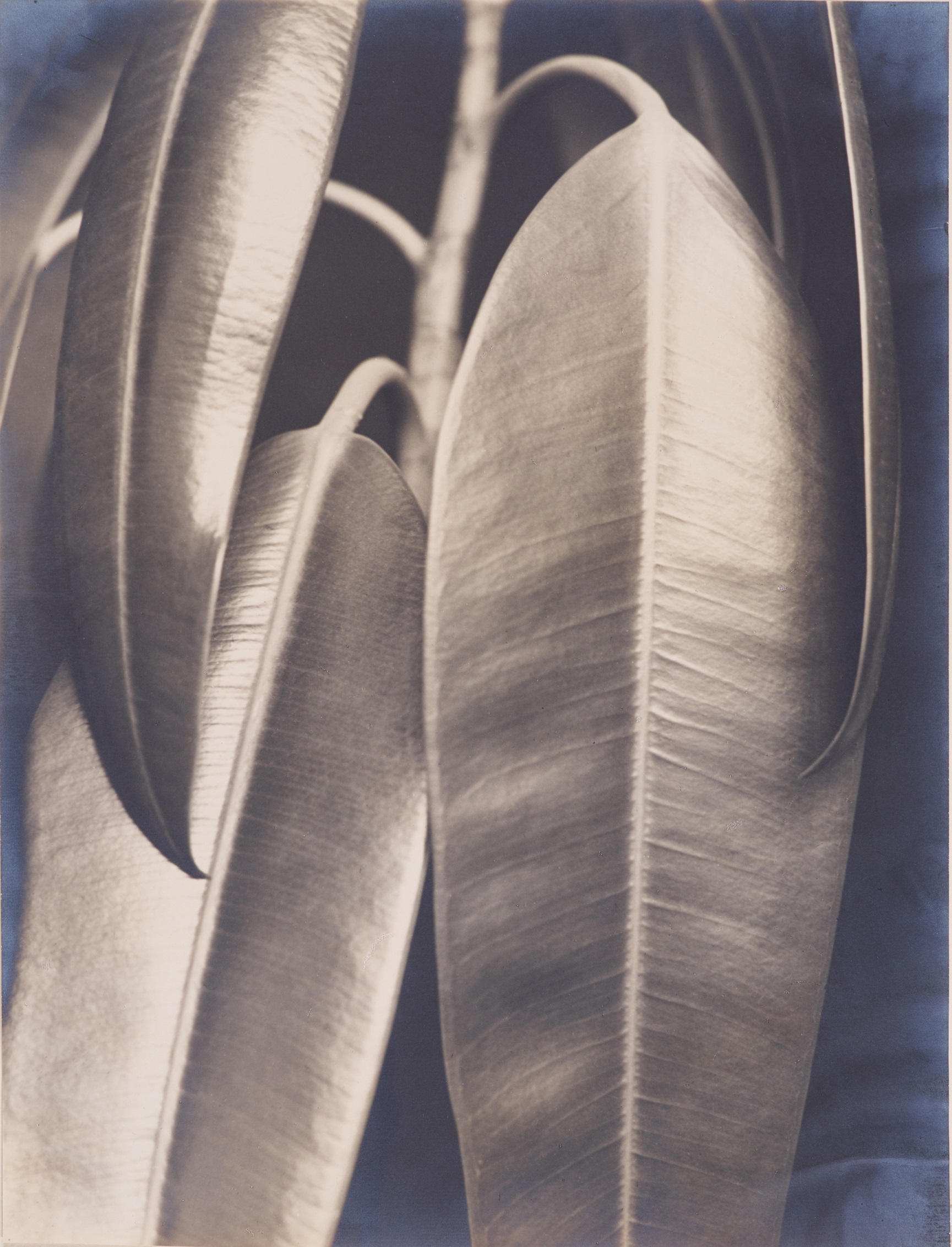

Aenne Biermann, Gummibaum, 1927 © Museum Folkwang Essen

From its invention, photography proved to be a more inclusive medium for women, who were not allowed into art schools or academies: discovering the possibilities of the camera by trial and error didn’t necessarily require formal instruction. From those looking at everyday life to the more conceptually adventurous, female photographers quickly covered all imaginable fields. The beautiful photographs of plants by Aenne Biermann, Alma Lavenson, and Tina Modotti come to mind; or taboo images of male nudes by Imogen Cunningham, Anne W. Brigman, and Harriet V.S. Thorne. These images seem to avoid objectification by foregrounding the sensual, even mystical aspects of the naked male body, whose formal beauty is sublimated into something easy to look at, but hard to define. In these pictures, the body is allowed to perform a non-pornographic erotics and to escape a reductive gaze unlike those of female nudes by their counterparts. In another critical position on the body, one segment of the exhibition is dedicated to self-portraiture, where subject and object collide and the photographer can take complete control over her final image. Madame D’Ora’s Selfportrait with Black Cat (1929) is an exquisite example: not only does the work show absolute mastery over material and light, it inscribes itself consciously into art history (references to Manet’s Olympia are on the horizon).

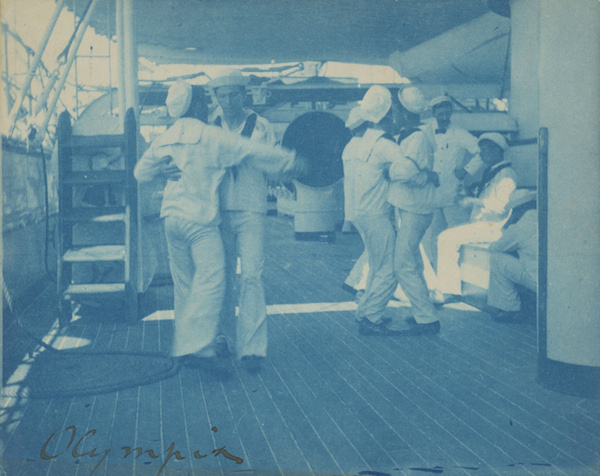

Frances Benjamin Johnston, Marins dansant la valse à bord de l’USS Olympia, 1899 © Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

However, in the realm of photojournalism, the exhibition makes its strongest argument for a gender-specific presentation. Notions of identity are performed in theaters of conflict, and domains formerly restricted by gender are pried open. Christina Broom’s underappreciated work (at least in the marketplace) for both the suffragettes and the British army, and Florence Farmborough’s pictures from the front lines of World War I, show when and how women photographers started to level the playing field. In the next war, photographers such as Gerda Taro, Julia Pirotte, Lee Miller, Margaret Bourke-White, and Joanna Szydlowska found their distinct voices. Taro’s brutal Air Raid Victim in the Morgue, Valence (1937) or Szydlowska’s images taken illegally inside a women’s concentration camp are vivid examples of their tenacity. Olga Vsevolodovna Ignatovitch, unfortunately, is the only example from the Soviet side of the Allied war effort. During “the great patriotic war,” as the conflict was called in the USSR, women chose to fight for their country either by taking up arms or picking up a camera. This subject would provide enough material for its own exhibition.

Frances Benjamin Johnston, Mills Thompson travesti, ca. 1895 © Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Simultaneously on view at the Musée d’Orsay is Splendeurs et misères. Images de la prostitution, 1850–1910, which focuses on women as passive objects of male voyeurism It’s a fascinating coincidence to have two exhibitions dedicated to “the feminine” in art history on view at the same moment. The prostitution show is a spectacle and has been extremely popular with audiences, which grants the more modest exhibition on female photographic practitioners an urgency it perhaps wouldn’t have had otherwise. Together, the exhibitions foreground the logic and task of the contemporary museum in catering to unquestioned tastes for “the feminine” and aim to confront audiences with what was at risk of being forgotten.

Elfriede Stegemeyer, Self-Portrait, 1933 © Digital Image Museum Associates/LACMA/Art Resource NY/Scala, Florence

Qui a peur des femmes photographes? takes the role of debunking the male gaze much more seriously than the exhibition on images of prostitution. Even so, it’s not a radical exhibition in a political sense: there is little overt activism in that it does not try to steer the audience towards a reductive interpretation of female photographers and their social suppression by men. The exhibition left me with a hunger for dedicated exhibitions on multiple aspects of the show that were only mentioned in passing. This broadness is a strength, but also points to the fact that the study of women photographers is still in an early phase. It’s impossible to imagine an exhibition dedicated to “male photographers”; in fact, it would rightly be considered absurd. Qui a peur des femmes photographes? 1839–1945 is a necessary exhibition that points to important women practitioners to whom we have been partly blind. One can only wonder what is still hidden in the archives.

Qui a peur des femmes photographes? 1839–1945 is on view at Musée de l’Orangerie and Musée de l’Orsay, Paris, until January 24, 2016.