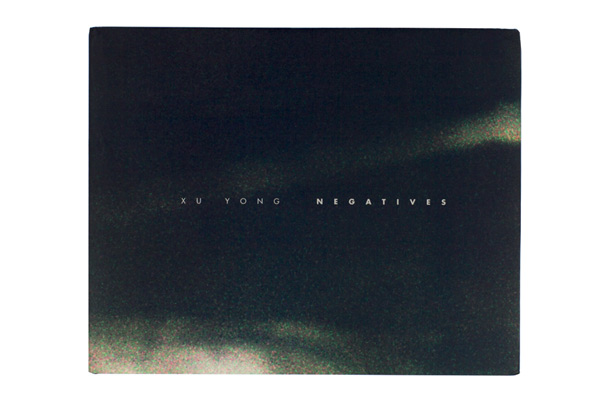

Stephanie H. Tung on Xu Yong Negatives

I don’t expect to be reaching for my iPhone when I open a book. Yet Xu Yong’s Negatives instructs me to do just that, in order to interact with its dark, eerie images through the phone’s lens. A quick change of settings inverts the colors on the screen, and the images in this slim volume burst to life. Suddenly, photographs of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests seem much closer to the present.

Negatives revisits some of Xu’s earliest, unpublished material from the beginning of his career: photographs of young protestors in the square, just before Chinese troops opened fire on the crowd on June 4. Xu’s rationale for printing his images of the protests—still a heavily censored subject in China—as color negatives is simple: negatives are less likely to be tampered with and therefore more reliable than normal photographs or digital media.

The act of using one’s phone to view these pictures also implicates the viewer in a way that looking straight at documentary photos does not. As the camera scans for a focal point amidst the crowd of students in the image, we too zoom around the composition, refocusing on one group declaring their hunger strike or another wielding a banner emblazoned with lines from Bei Dao’s poem “Proclamation” (“And we will not fall to the ground / Allowing the executioner to look tall / The better to obscure the wind of freedom”). There’s so much life, hope for democracy, and anger at the Communist government in these images. The only hint of the violence to come appears in the ominous photo of a tank on the last page, seen from behind a tree. Xu’s images allow us to inhabit the photographer’s point of view, watching and framing the unfolding events through our own devices.

As a documentarian, Xu is a prolific creator of photobooks, often adapting existing technology to suit his purpose. In the months after Tiananmen, Xu took pictures of the vanishing hutong alleyways in his neighborhood and published the pioneering work Beijing Hutong: 101 Photos (1990). He followed this with a number of innovative projects, including more recently This Face (2011), which documents the face of a single prostitute over her day of work. The preservation of history and memory, both collective and personal, in the shadow of authority is the thread running through his work.

At a time when the Chinese people’s collective memory of Tiananmen is lapsing, these images—hidden for over twenty-five years—act, in Xu Yong’s words, as an “immunization against amnesia” and a means to reconsider the social and historical circumstances of their creation. There is undoubtedly a sense of urgency in Xu’s project, and in Negatives, he points to the tenuous relationship between photography, truth, and history. It is only fitting, and perhaps politically prudent, that once the iPhone is turned off, the pages revert back to dormant abstractions.

Stephanie H. Tung is a PhD candidate focusing on modern and contemporary Chinese art at Princeton University. She is a contributing author to the Aperture volume The Chinese Photobook: From the 1900s to the Present (2015).

Xu Yong

Negatives

New Century Press • Hong Kong, 2015 (second edition)

Designed by Liu Song • 12 1/4 x 9 7/8 in. (31 x 25 cm)

72 pages • 54 color images • Hardcover with jacket

newcenturymc.com

• Shortlisted for a 2015 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Award