Zarina Bhimji’s Poetic Confrontation of Postcolonial History

In her solo exhibition in Sharjah, the Ugandan-born artist reclaims overlooked narratives about Arab-Africa relations.

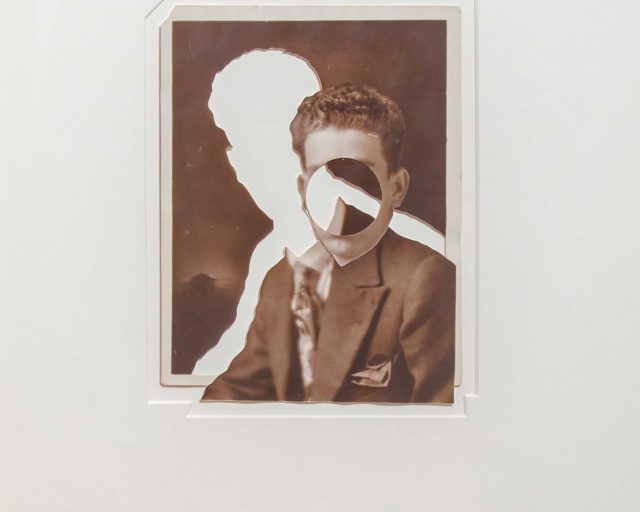

Zarina Bhimji, Still from Yellow Patch, 2011

The word that stayed with me the longest after seeing Zarina Bhimji’s exhibition Black Pocket was the one that I couldn’t read. It hovered in the middle of a handwritten letter—an excerpt of which had been photographed, blown up, and hung high above our heads at her recent solo show at the Sharjah Art Foundation, United Arab Emirates. The phrase “the Abolition of Negro … in his Domain” and the dates “1857, 58 & …” were clear, but in between them, the meaning of a word that resembled “Risirial,” or perhaps “Virinial,” remained just out of reach. It is often the unknown that haunts us the most: the things we cannot decipher, the things we long to learn, and the things we cannot bring ourselves to confront. The elusiveness and ambiguity of this photograph extended to the installation in which it appeared, Lead White (2018)—made up of enlarged images of colonial-era letters, stamps, and maps—rendering it devoid of a singular reading.

What is palpable through the polyphonic nature of Lead White is the power that resides in language: a small signature or seal having had enormous consequences on faraway lands and bodies. Bhimji has spent the last decade forensically looking at such details in documents found at the Zanzibar National Archives, where many of these images were taken, as well as absorbing broader forms of knowledge and rich oral histories from elders in Zanzibar. Based in the U.K., Bhimji ’s fertile research in East Africa and India is largely birthed through photography and film. Bhimji was born in Uganda in 1963, but fled the country at the age of eleven, when General Idi Amin forcibly expelled 80,000 Asians. The artist only returned when she was thirty-five. “We had the experience but missed the meaning,” Bhimji says of this harrowing time, quoting T. S. Eliot, before adding “you can never go back.”

Photograph by Shanavas Jamaluddin, Sharjah Art Foundation

According to some sources, Asians in East Africa were always seen as provisional citizens or colonized colonizers, as they were brought in under the aegis of the British Empire, and were middlemen in a three-tiered system, wedged between the British above and the Africans below. Others say that members of these Asian communities became twice migrants or double diaspora once expelled to hostile Britain in the 1970s. Bhimji purposely eschews such categorization, identifying neither as Indian nor African, neither as man nor woman. Bhimji’s work, too, opts for nuance and complexity, poetry and abstraction. This approach seems to fit with scholar Maya Parmar’s suggestion of likening the hybridity of cultures and traditions to multilingualism—as additional lenses or perspectives rather than opposing ones. Bhimji can easily flow between Gujarati, Kutchi, Hindi, Swahili, and English.

When Bhimji initially struggled with English, she says that it was Sarat Maharaj who supported her application to Goldsmiths, University of London. Mentored by figures such as Maharaj and Stuart Hall, and friends with the artists Eddie Chambers, Isaac Julien, and Sonia Boyce, it was in London that Bhimji became part of the British Black Arts Movement of the 1980s (in Britain, anyone nonwhite was often called “Black,” and anyone from the Indian subcontinent was simply labeled as “Asian”). This was the heyday of collectives Sankofa, Autograph ABP, and Black Audio Film Collective, all of which challenged the notion of the diaspora as a homogenous entity. Bhimji’s influences were always diverse, from Alfred Stieglitz and Julia Margaret Cameron, to films such as Kamal Amrohi’s Pakeezah (1972) and those by Satyajit Ray. However, it was Iranian cinema, and particularly Samira Makhmalbaf’s Blackboards (2000), a poignant film about teaching children how to write, that spoke to Bhimji the most. She was forever interested in “forms that release love, joy, tenderness, and grief,” she says.

Photograph by Shanavas Jamaluddin, Sharjah Art Foundation

Bhimji’s Yellow Patch (2011), one of three elegiac films shown in Black Pocket, similarly privileges affect, texture, painterly visuals, and sonic composition over plot. An empty bureaucrat’s office piled high with forgotten files against the noise of traffic and thunderstorms, a crumbling statue of Queen Victoria layered with sounds of people playing cricket, unfinished boats by the side of a soulless harbor, and decrepit havelis taken over by nature locate us within the vestiges of colony. While audio clips of Lord Louis Mountbatten, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Mahatma Gandhi serve as identifiers of the Partition of India in 1947, sounds of birds and rain evoke atmosphere and sentiment far more strongly. In one moving moment, the camera zooms in on a deeply cracked brick wall—the unnatural zigzag reminiscent of human-made lines drawn in the earth. The image is intensified by an all-engulfing, disturbing, rumbling noise that slowly crescendos.

Sound is paramount to Bhimji. The artist speaks of the microphone as akin to the photographic lens when recording things—always conscious of pursuing translation over truth. Such slippages between cultures and histories could be felt when viewing the photograph Memories Were Trapped inside the Asphalt (1998–2003), depicting an outer room in a Ugandan mosque, in one moment, and hearing the azaan (Islamic call to prayer) from the mosque adjacent to the gallery in another. Sharjah also shares a similar past of occupation, invasion, and British colonialism. Hoor Al Qasimi, the curator of Black Pocket, reveals that scholars have been exploring such linkages and crossovers since the first Arab-Africa relations conference held in Sharjah in 1976. Staging exhibitions such as Bhimji’s in Sharjah can be seen as a way of reclaiming these overlooked narratives, and presenting them with all their contradictions, uncertainties, and gaps—an empowering act of speaking back.

Photograph by Shanavas Jamaluddin, Sharjah Art Foundation. All works © the artist/DACS/Artimage

It was only much later that I realized the word in Lead White that I couldn’t read was most likely Vicirial—a word that denotes domination and subjugation, a word that is long gone from daily use, though the impact of empire remains. Underlying the desire to understand the meaning of a word, image, or compilation of objects is the need to fix, locate, and order them into a straightforward and linear story. Instead, the close encounters with fragments of language and landscape in Bhimji’s work force us to contemplate the power, beauty, violence, and trauma that endure in traces and interstices. This, in turn, may reflect the ambiguous and unresolved nature of living with unacknowledged questions, and the impetus of returning to them again and again. What happened on either side of the story? Where does it start? Who else’s story is this? Who didn’t make it in to begin with?

Zarina Bhimji: Black Pocket is on view at the Sharjah Art Foundation, United Arab Emirates, through April 10.