Pictures, like songs, should be left to make their own way in the world. All they can reasonably ask of us is that we place them on the wall, in the best light, and for the rest allow them to speak for themselves.

—Frederick Douglass, “Lecture on Pictures,” 1861

Frederick Douglass understood that a picture could do its work with little fuss, communicating clearly and directly, yet with considerable power. Knowing this, he praised the picture-making arts broadly but particularly welcomed the new medium of photography because it put this tool within everyone’s reach. Young or old, man or woman, Black or white—everyone could experience the power of this new medium by looking at a photograph, yet so, too, could everyone wield it by being photographed. It was, as numerous people have claimed, a truly democratic medium. Even “the humblest servant girl” could now afford to have her picture made, and many did. Douglass himself, a former slave who became a leading abolitionist, was the most photographed American of the nineteenth century, and each time he sat for a portrait, he knew precisely what he was doing. Show the world what I am—what we are—his portraits seem to say; show them that the camera, like nature, cares not one whit about skin color, or any other detail, but instead records everything equally and without prejudice. In this sense, at least, photography was indeed democratic: it could be used by practically anyone to suit their purpose. Douglass, for one, although a great man of words, again and again let the pictures speak for themselves.

But Douglass was not attracted to photography solely on account of its affordability, flexibility, and supposed objectivity. He also found in the practice of photography evidence of human nature. “The power to make and to appreciate pictures belongs to man exclusively,” he told a Boston audience on December 3, 1861, and repeated on more than one occasion. Picture making, he said, was a peculiarly human endeavor. People the world over, regardless of color or culture, were fascinated with pictures—making, sharing, and posing for them in vast numbers. The ability to make pictures, he reasoned, was therefore evidence of one’s humanity. That such a test was necessary, that Douglass had to posit photography in this way—arguing that it was “an important line of distinction between man and all other animals”—reminds us where he lived and when: the slaveholding, segregated states of America.

Douglass specifically aimed his contention “that man is everywhere a picture-making animal” at the men who comprised the “American school” of ethnology in the mid-nineteenth century, including Josiah C. Nott and George R. Gliddon, authors of the popular compendium of racialized science Types of Mankind (1854). “The Notts and Gliddens,” as Douglass called this group, insisted and labored to prove that humans were not of one kind the world over, but belonged to distinct and permanent types: “races.” These men sought in particular to prove that humans of one type, Africans and their descendants, were not only inferior to whites, but formed an altogether different species. Louis Agassiz, the Harvard professor who did much to bring the scientific debate on human diversity into public view, was one of “the Notts and Gliddens”—indeed, he contributed a chapter to Types of Mankind—and Douglass often singled him out in his lectures. When Douglass took to the podium to argue against these men’s ideologies dressed up as natural science, whose theories influence our political discourse even today, nearly two hundred years later, he often did so by celebrating picture making in general and photography in particular.

In 1850, Joseph T. Zealy, a Columbia, South Carolina, photographer, produced a group of daguerreotypes of Africans and African Americans for Agassiz to support his ideas on the origins of human diversity. It is not known if Douglass was familiar with these images, but they surely would have made their mark upon him if he had known them—as they have on so many viewers since their discovery in the attic of Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in 1976. The images of Delia and her father, Renty; of Alfred, Fassena, and Jem; and of Drana and her father, Jack, possess all the immediacy and power of which daguerreotypy was capable. But what do they say? Douglass once remarked that pictures should be allowed to “speak for themselves,” yet this is a tricky proposition. Images do not hold a single, unwavering message for all time; pictures can and frequently do change their meaning. The daguerreotypes were created to speak the language of the “Notts and Gliddens,” and they perhaps did fulfill this purpose, or something close to it, particularly for Agassiz and others who shared his views. But the pictures speak other languages as well, telling other stories, some of which refute the efforts of the “American school” of ethnology.

Of course, there is much that the pictures can’t tell us, not of their own accord. They can tell us nothing of the scientific examination each person endured at Agassiz’s hands prior to being photographed; nothing of what Delia thought about the Taylor family, her putative “owners,” or exactly where in Africa her father, Renty, had been born—these are all matters about which the historical record is largely silent and the images altogether mute. A daguerreotype cannot speak with any certainty of a lifetime experienced by a single consciousness, a particular subjectivity. Pictures, like songs, do make their own way in the world, as Douglass said, and they speak to us on their own terms, but they also need interpretation. They speak to us so that we might listen, ask questions, and then turn to others and recount what we have learned.

*

From the outset of the project that led to this volume, it was clear that the daguerreotypes made for Louis Agassiz required an interdisciplinary and collaborative approach in order to responsibly analyze the images and to uncover new information about their history. Two workshops organized by the Peabody Museum and held at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study brought together scholars of documentary photography, memory, slavery, anthropology, American history, African American history, and the history of science to discuss the daguerreotypes and critique one another’s writing on them. This diversity of expertise allowed for a focused yet wide-ranging discussion, and the collaborative approach established at the workshops was carried through the editorial process. Throughout the project, our goal has been to give voice to the many ideas, contexts, and viewpoints that contributed to the making of these fifteen daguerreotypes and the responses that they evoke today. The goal, in short, has been to both listen to and speak of the daguerreotypes without concern for arriving at a definitive, final word on them or any aspect of them.

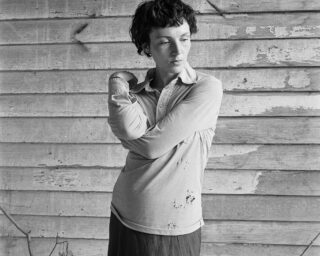

Owing to this approach, the contributors to this collection address a number of interrelated topics. Following an introduction on how the daguerreotypes came to be made, the authors explore the identities and experiences of the seven people depicted in the daguerreotypes (Gregg Hecimovich); the value of photography to a new nation founded on (but struggling with) principles of democracy (Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Matthew Fox-Amato, John Wood); the close relationship between photography and science, and between photography and memory (Tanya Sheehan, Christoph Irmscher); the overlapping intellectual contexts that made the creation and display of such images possible (Manisha Sinha, Harlan Greene, Sarah Elizabeth Lewis); and responses to those ideas at the time in which the images were made (John Stauffer). More recent responses are also explored, including considerations of the institutional life of the fifteen daguerreotypes and the ways in which artists have used them to extend the critique of scientific and institutional racism into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries (Carrie Mae Weems, Deborah Willis with Carrie Mae Weems, Ilisa Barbash, Robin Bernstein, Keziah Clarke, Jonathan Karp, Eliza Blair Mantz, Reggie St. Louis, William Henry Pruitt III, Ian Askew). New photography by Carrie Mae Weems provides a visual counterpoint to many of the issues raised throughout the volume.

The approaches taken by the contributors to this collection vary widely, which is a strength of the enterprise. The nature of these differences may be illustrated with a simple question: What should we call the fifteen daguerreotypes? Are they the Zealy, Agassiz, or Peabody daguerreotypes? Who, ultimately, is responsible for them? To whom do they belong? The artist, the scientist, the institution—or the subjects of the images?

This question of ownership is a deeply uncomfortable one, given that the subjects of the images were enslaved. One way to elide the problem is to refer to the images by the names of their subjects, to use the names of individuals to indicate the group as a whole: Jem, Fassena, Alfred, Delia, Drana, Jack, and Renty. Doing so, however, can make for a long and at times repetitive string of names. It may also render the daguerreotypes—fifteen images of seven individuals—as a conglomerate. Using the names of enslaved persons should also be questioned because names were typically assigned by enslavers: “Delia” is what members of the Taylor family called the woman Zealy photographed—we know this from the records they kept—but her family and familiars may have known her by a different name, a name that we will never know. Another thorny question with respect to naming is whether Fassena should be uniformly called Fassena, as he is identified in the label affixed to his daguerreotype or George Fassena, the name he used post-emancipation. These questions of representation and identity cut deep into the histories of the images, the people depicted in them, and the purposes for which they were made and used.

When writing about the daguerreotypes, one must also face the question of whether nineteenth-century ethnology can rightfully be called a science. Science as we understand it today was then just beginning to take shape, to be codified as a profession determined by a specific set of practices. The comparative study of crania and other physical characteristics, which Nott, Gliddon, and others included in their definition of “ethnology,” may have been considered scientific in its day—it was an investigation into the natural world undertaken by men educated in medicine, anatomy, and various strands of natural history, including geology and paleontology. Yet to call their version of nineteenth-century ethnology a “science,” and polygenesis a “scientific theory,” lends these practices twenty-first-century legitimacy. To refer to these ideas as “pseudoscience,” on the other hand, while anachronistic, signals a critical stance. In the essays comprising this collection, each scholar and artist has taken her or his own approach to these and other issues, deciding how best to frame their discussion of the daguerreotypes. The editors have made no attempt to reconcile the different approaches, for this would be tantamount to smoothing over fissures that are very much a part of the daguerreotypes’ difficult history and ongoing legacy.

While the critical approaches in this volume vary greatly, the authors nevertheless shared an important experience: namely, the sense on viewing the fifteen daguerreotypes that a response of some sort was absolutely necessary. “Once seen, the images are hard to forget,” Sarah Elizabeth Lewis writes of encountering Delia and Drana with their clothing pulled down to their waists. Manisha Sinha calls them “Louis Agassiz’s collection of disturbing daguerreotypes.” These images, Harlan Greene notes, hold “as compelling a place in our national imagination as those photos of Black students, in their crisp 1950s outfits, integrating schools, with the hate-contorted faces of whites shaking their fists around them.” Everyone involved in this collection has been moved by the daguerreotypes and feels an obligation to Delia, Renty, Alfred, Fassena, Jack, Drana, and Jem. One cannot simply look at George Fassena—one must also endeavor to see his suffering at the hands of the slaveholder, the scientist, the photographer, and, yes, even the historian. One must, in other words, relate to each of the people in these images, inasmuch as this is possible across time, geography, race, gender, class, and culture. One must seek to understand, and then make something of this experience.

There is another point of intersection among the authors of this volume, and that is the conviction that the images failed utterly in their original purpose. Intended to represent racial types and defend the idea that different groups of humans were and always have been distinct species, thus opening the door to the abuse of one group by another, the daguerreotypes instead present to us seven individuals who endured the manifold terrors of slavery with dignity and humanity. Zealy’s images—which have been used in books and magazine articles, on conference posters, in documentary films, and elsewhere—have become simple visual representations of slavery. They are, in other words, iconic images of the institution they were meant to buttress but which they now pointedly indict by showing us the effects of enslavement on individual bodies and allowing us to look into the eyes of those who suffered. The original evidentiary purpose of the daguerreotypes has been turned completely on its head.

And yet, even as the meaning of the daguerreotypes can be reduced to a single concept slavery—each image also gives us the likeness of a particular man or woman. Alfred is Alfred: he is not a slave, not a victim, not a type, not a lesser being than the men who took his picture or those people, like us, who gaze upon it. He is a man who drew breath and walked the same ground we traverse today. Moreover, while researching and writing about Delia’s humiliation is painful, to say nothing of how it feels to look closely at her photograph, it is remarkable that we are able to see her at all. Millions of women lived and died under slavery, their stories buried together with their bones in unmarked graves, yet we know so much about Delia, including her name, her father’s name, where she lived, and even—perhaps especially—the contours of her face. In this sense, the pictures do indeed speak for themselves.

The inversion or backfiring of the daguerreotypes’ original intent may be due to the nature of photography, a technological means of reproduction given to manifold interpretations, or it may be due to the inherent flaws of the precepts followed by certain nineteenth-century thinkers. Perhaps it is simply poetic justice. Regardless, the failure of the daguerreotypes to perform the ideological purpose for which they were made is one of those twists of fate that history sometimes permits, and it is celebrated throughout the essays and new photography collected in this volume.

*

That the meaning or function of the daguerreotypes has reversed itself over time, that the viewer’s response to the photographs today is often expressed as recognition of the subjects’ shared humanity rather than their difference, undoubtedly has much to do with the passage of time and the clarifying lens of history. The daguerreotypes are no longer the property of a scientist who embraced white supremacy; they are instead curated by an institution devoted to the study and preservation of human cultural history and diversity, steeped in the anthropological method of ethnology, the comparative study of cultures. Now they are not so much the result of scientific inquiry into the origins of human diversity as they are an object lesson in how political expediency can influence intellectual matters that are all too often considered separate from social power and those who wield it. The daguerreotypes have changed with time in a fundamental way. Nevertheless, the motivation behind their creation and acquisition is still very much with us.

Racism persists, and the concepts of racial types and racial hierarchy, while deriving from scientific modes of inquiry, have largely left science behind to take root in various segments of American culture. To deny another human being rights equal to those you enjoy on the basis of skin color is to elevate yourself for no reason other than that it suits you. To dismiss a person’s humanity, whether by word or deed, is to say, I am better than you because I was made that way. Embedded deeply within such acts of discrimination lies the hierarchy so dear to “the Notts and Gliddens” of the nineteenth century. Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, introduced in 1859, may have largely put to rest among the scientific community debates about the mechanism by which organisms change and grow diverse over time, but it did not put an end to ideas fueling those debates. White supremacy has no need for science because it has become integral to the status quo: the same nexus of ideas that moved Agassiz to declare that Africans were of “a distinct origin” from Europeans thrives today within our institutions and our culture.

Since the advent of photography, African Americans have used the medium to combat racism, including stereotypes and other expressions of racial prejudice—as is attested by the success of early Black photographers, Frederick Douglass’s many portraits, W. E. B. Du Bois’s American Negro exhibition for the 1900 Paris Exposition, and many other examples from the history of photography. More recently, however, developments in photographic technology have enabled another order of response, one that is also a kind of reversal—namely, the turning of cameras on oppressors to catch them in the act of harassment, abuse, and murder. Racially motivated violence in this country is not new, but the ability to show the world what is happening as it happens certainly is. Technology is no longer controlled exclusively by those in power. Recordings made by witnesses of violence with their mobile phones have exceptional evidentiary value due to their real-time, documentary nature and also their growing ubiquity. Such images, Douglass might agree, really do speak for themselves. This is not to suggest that mobile phone recordings do not require analysis and contextualization—they, like all images, most certainly do—but to acknowledge that they also communicate meaning clearly, directly, and with considerable force.

This collection of essays and images, a work of historical, cultural, and creative inquiry, is firmly grounded in the events shaping our lives today. At this moment and in these divided states of America, perhaps more than at any time since their rediscovery in 1976, the daguerreotypes of Jem, Alfred, Delia, Renty, George Fassena, Drana, and Jack command our attention, demanding that we look closely, listen intently, and speak out—however difficult this may be—giving voice to all that we have learned.

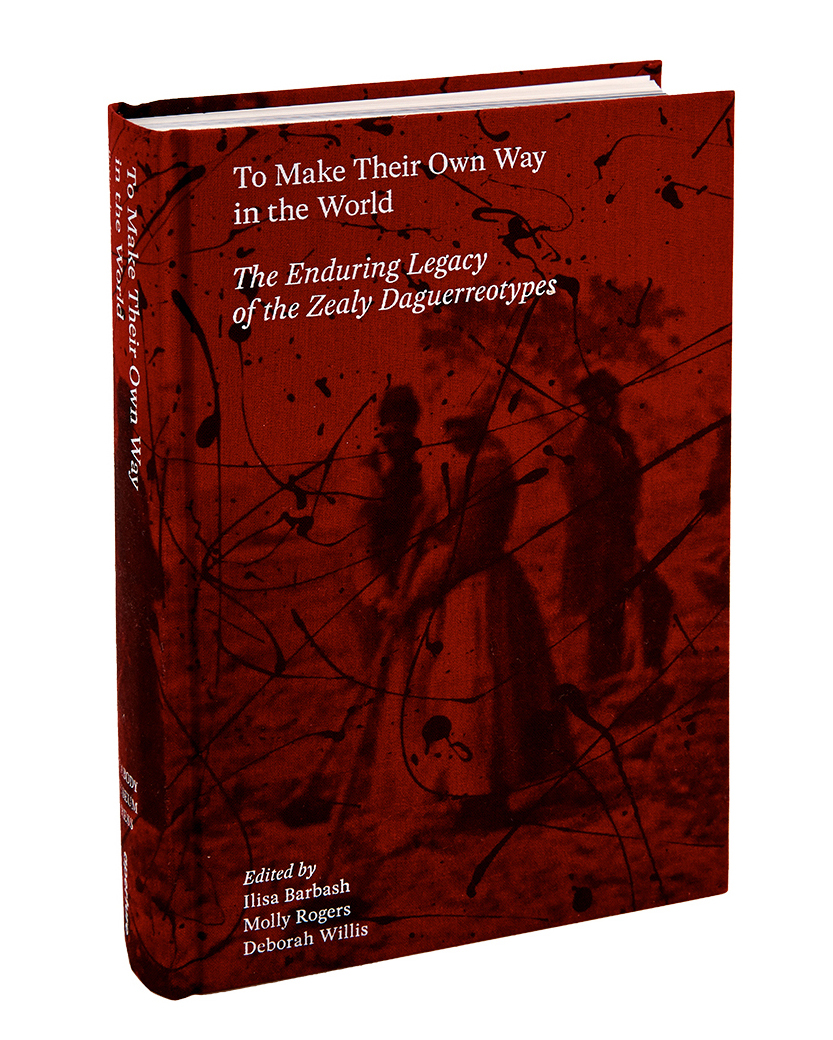

This introduction is from To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes (Aperture/Peabody Museum Press, 2020).