Museums and archives today are in the throes of profound change as they grapple with the fraught legacies of colonialism, imperialism, and slavery—all of which played fundamental roles in building cultural institutions of the Western world. Exploring and acknowledging the complex histories of their institutions, scholars and museum professionals are scrutinizing with new eyes the objects, documents, and photographs housed and curated in these collections.

Such efforts, at their best, represent a challenge to long-held assumptions, as well as a deep commitment to broad and diverse perspectives on cultural heritage and on what it means to research and interpret museum and archival collections. Museums around the world are recognizing the imperative to open their collections to creative, transformative partnerships and collaborations with members of descendant communities.

The Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard exemplifies the type of elite institution that benefitted from American nation building: international and domestic enterprises that both supported exploration and research, and removed from communities of origin a wealth of cultural materials. The daguerreotypes that are the focus of this volume are among those materials: vivid and visceral records of our country’s original sin of slavery.

These fifteen unique photographs of two enslaved women and five enslaved men came to Harvard as records of human difference, acquired in 1850 by Harvard professor of geology and zoology—and founder of the Museum of Comparative Zoology—Louis Agassiz. Agassiz intended to use them as evidence to support his theory that humans were descended from separate creations and that Blacks, in particular, were inferior to whites.

Even at the time, this theory was challenged by other scientists, and it was ultimately refuted by Charles Darwin. When the daguerreotypes were rediscovered at Harvard in 1976, they had not been seen in over one hundred years. Their rediscovery made headlines, and the photographs have been prominent in the awareness of Black Americans, of descendants of slavery, and of scholars and artists ever since. They are evidence of pain, coercion, exploitation, and tragedy—and Harvard played a role in that.

When Harvard President Lawrence S. Bacow announced the university-wide Initiative on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery in November 2019, this book was already written. Seven years earlier, the Peabody Museum had convened the first of two seminars hosted by the Radcliffe Institute that brought together a range of thinkers and scholars with the goal of confronting again the significance, and the very existence, of these images. It is impossible to undo the evils of the past, but Harvard and the Peabody take seriously the obligation, articulated by Bacow, “to understand how our traditions and our culture [at Harvard] are shaped by our past and by our surroundings—from the ways the university benefitted from the Atlantic slave trade to the debates and advocacy for abolition on campus” before, during, and long after the Civil War. “It is my hope,” Bacow writes, “that the work of this new initiative will help the university gain important insights about our past and the enduring legacy of slavery— while also providing an ongoing platform for our conversations about our present and our future as a university community committed to having our minds opened and improved by learning.”

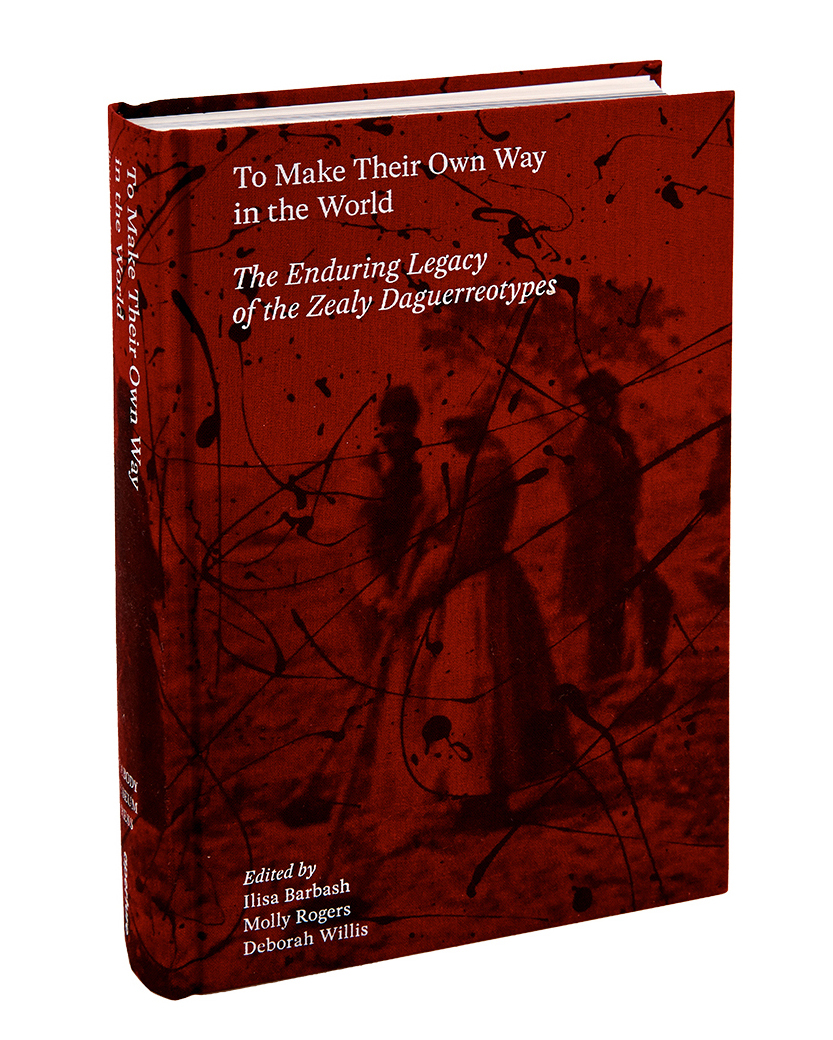

The multidisciplinary and collaborative research that went into the creation of this book represents one step in the Peabody Museum’s participation in this larger initiative—an effort to explore the lives and acknowledge the contributions and unimaginable suffering of Alfred, Delia, Drana, Fassena, Jack, Jem, and Renty—and millions like them whose names are lost to history. We hope the publication of To Make Their Own Way in the World will stimulate dialogue and critical thinking, expand awareness and sensitivity, and encourage community involvement in ways that help bring the museum to the world—and the world into the museum.

This preface is from To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes (Aperture/Peabody Museum Press, 2020).