Okwui Enwezor: Many people know you as a renowned photographer from Nigeria, by way of Cameroon and then the Central African Republic. Each of these countries has played a role in your conception of your identity. So, I would like to start—partly to clear up some misunderstandings about your biography—by asking you where you were born and when.

Samuel Fosso: I was born in Kumba, West Cameroon, in 1962, to Nigerian parents. At the time I was born, I was sick and partly paralyzed—that was why my mother took me back to Nigeria, for a local cure. My grandfather was what was known as a “native doctor.” After the treatments in Nigeria, my mother wanted to bring me back to Cameroon. But this was in 1967, and the Biafran War in Nigeria had started. It was impossible to travel. My mother died during this period, so I stayed with my grandparents in Nigeria until the war ended in 1970. I had an uncle in Cameroon who came back to Nigeria to take me with him. We stayed in Cameroon only for six months, because by this time—it was around 1972—my uncle had relocated to Bangui in the Central African Republic, and I moved with him again. I lived with him in Bangui for several years until I started my photographic career.

Enwezor: What did your uncle do for a living?

Fosso: He was a shoemaker, producing women’s shoes. In fact, when he brought me to Bangui, he had me working with him to make shoes.

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: You must have been very young.

Fosso: Yes. I was around ten years old when I started working with him. One day, in 1975, on my way to the market to go food shopping for his wife, I saw a photographic studio owned by a Nigerian man from Imo State. Usually, after I finished my housework, I went to rest near where this studio was. It was on one such occasion that I asked the owner of the studio if it would be possible for him to teach me to be a photographer. He agreed, but said that before he could take me in as an apprentice he would need to consult with my uncle. I then asked him what it would cost to learn from him in order to make sure that my uncle agreed. He said the training would cost nothing since the Central African Republic functioned at that time like the French system, where apprentices are paid for their work, unlike the English system in Nigeria, where they don’t pay you.

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: What kind of work did you do in the studio while you were learning?

Fosso: When you are employed as an apprentice, your work involves everything—sweeping the studio, errands, and more. I was very eager to start photographing, but for about one month I did not even touch the camera.

I became impatient and went to the photographer and asked him how long it would take before I could start photographing. He told me it was not a quick process and that I should continue working on the assignments he gave me. Then I found another way, through his assistant, to whom I offered my breakfast money every day for additional instruction. This way, I could learn the job more quickly. It was from then on that I really began to learn to make pictures.

Enwezor: What year did you start this apprenticeship?

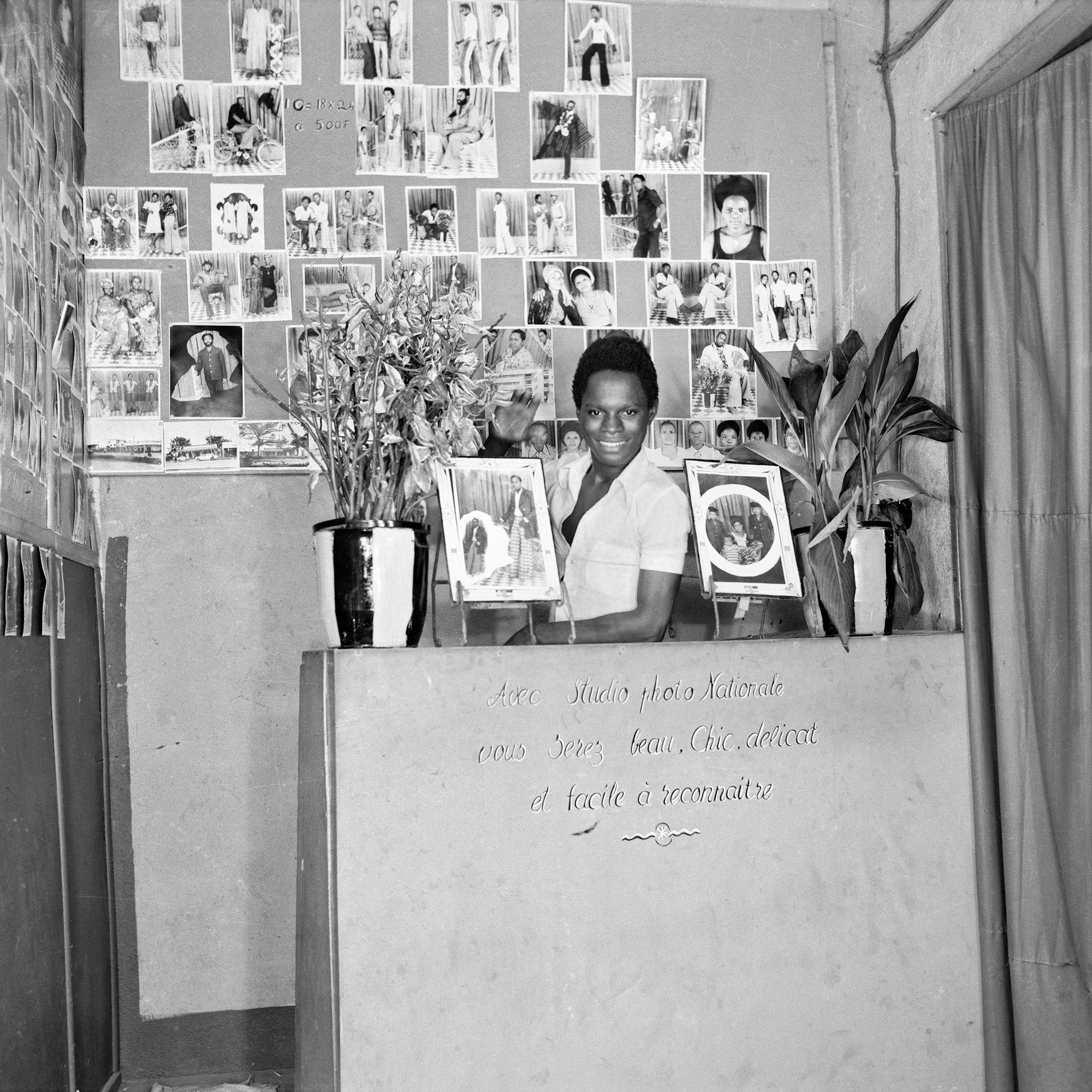

Fosso: I worked at the studio for about five months, between October 1974 and March 1975. And in September 1975, I opened my own studio.

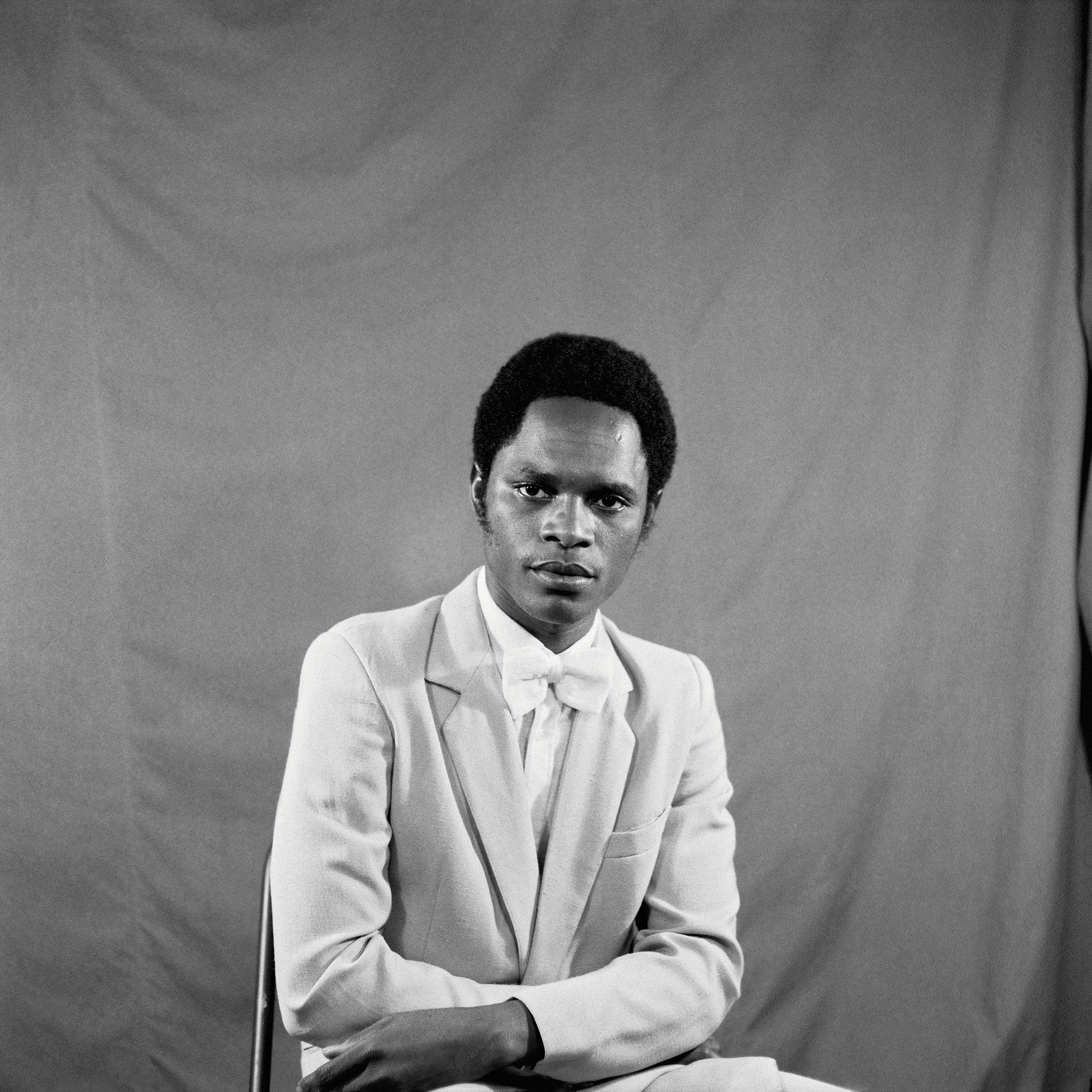

Enwezor: You were only thirteen years old. Were there other photographers your age in Bangui at this time?

Fosso: None. There was not a single one. The majority of the photographers were Nigerians and Cameroonians. I was very young, and people sometimes wondered about me when they came to have their pictures taken in the studio.

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: Conceptually, the photographs you made were very sophisticated, and would have been even for someone who had been practicing photography for a very long time; for me, this still remains a big point. You were not yet a photographer, but you picked up the techniques very quickly.

Fosso: Before I opened my studio on September 14, 1975, I was already working as a street photographer. So, my training and base of knowledge were ongoing. I was constantly learning.

Enwezor: Do you remember which camera you first worked with?

Fosso: It was a Kodak camera, a small six-by-nine, with only nine images in each roll of film. It was larger than a six-by-six lens. After taking the pictures, I would go to the studio where I had trained to have the film developed.

In early September of that first year, my uncle flew to Douala, Cameroon, and bought a larger camera for me and told me I had to find a studio for myself. There was a Nigerian-owned studio I knew of, which was free because it had been closed. This was where I established my first studio.

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: I want to discuss the moment when you moved from merely making photographs to becoming an artist. When do you think your work as a photographer shifted from making photographs on commission for your clients to making images for yourself?

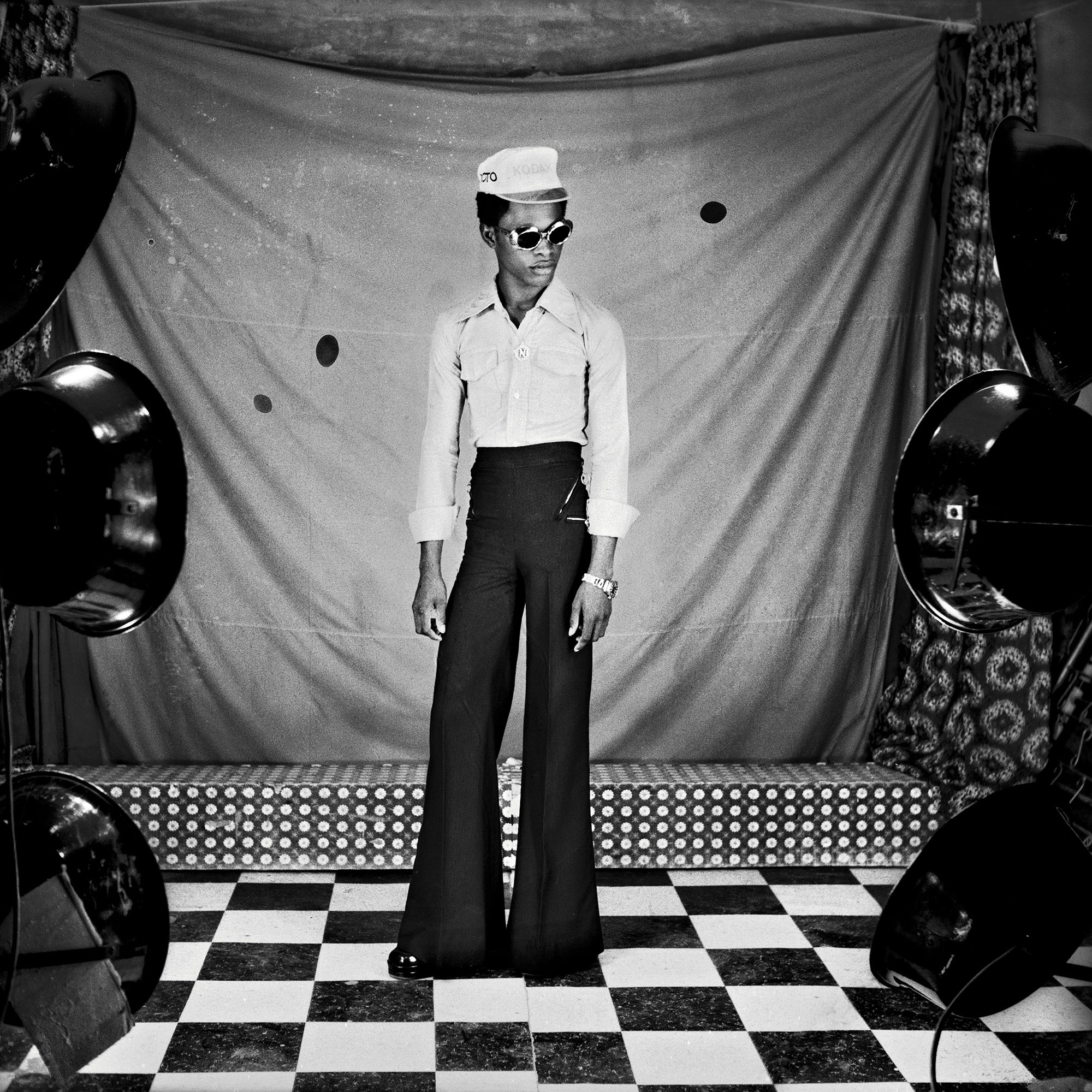

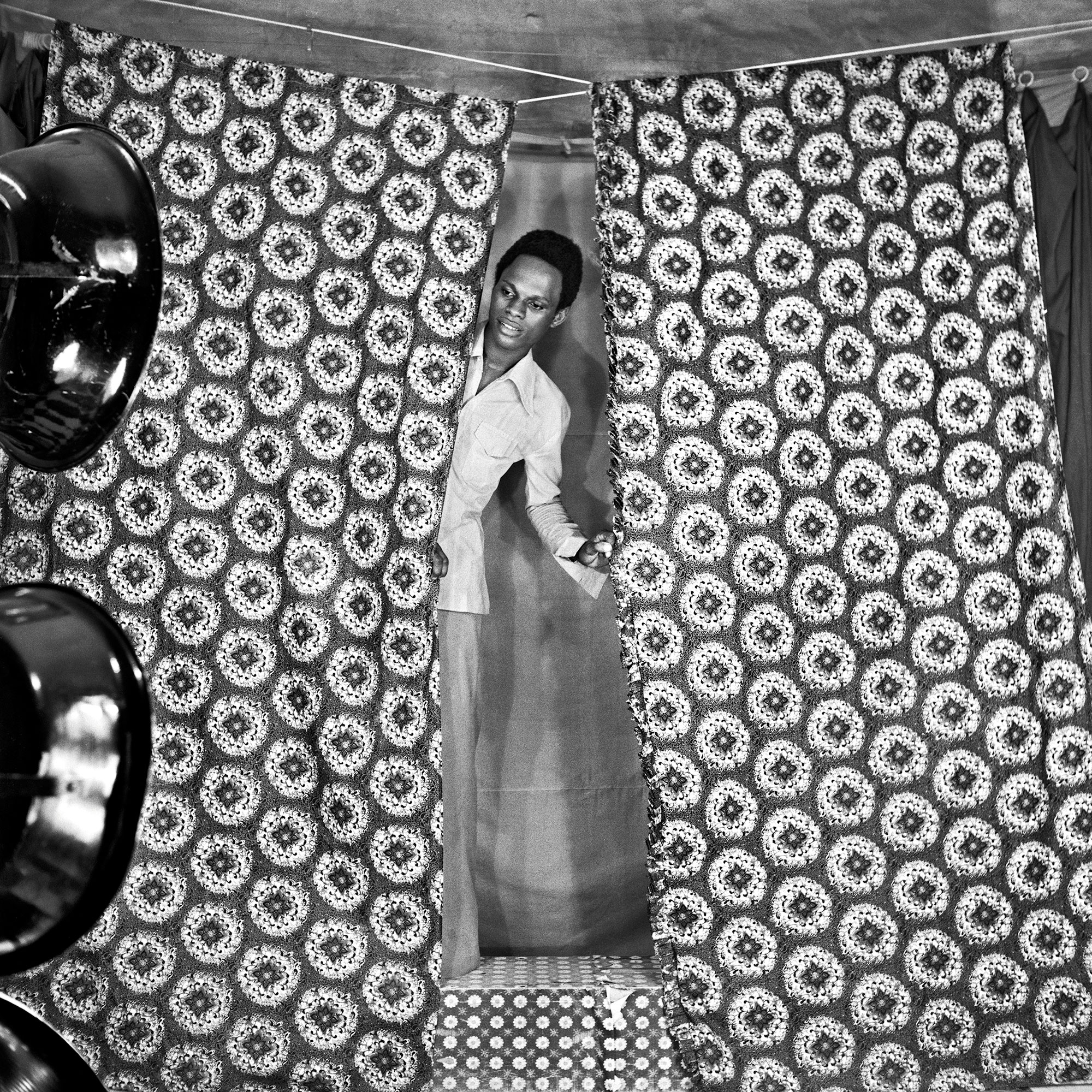

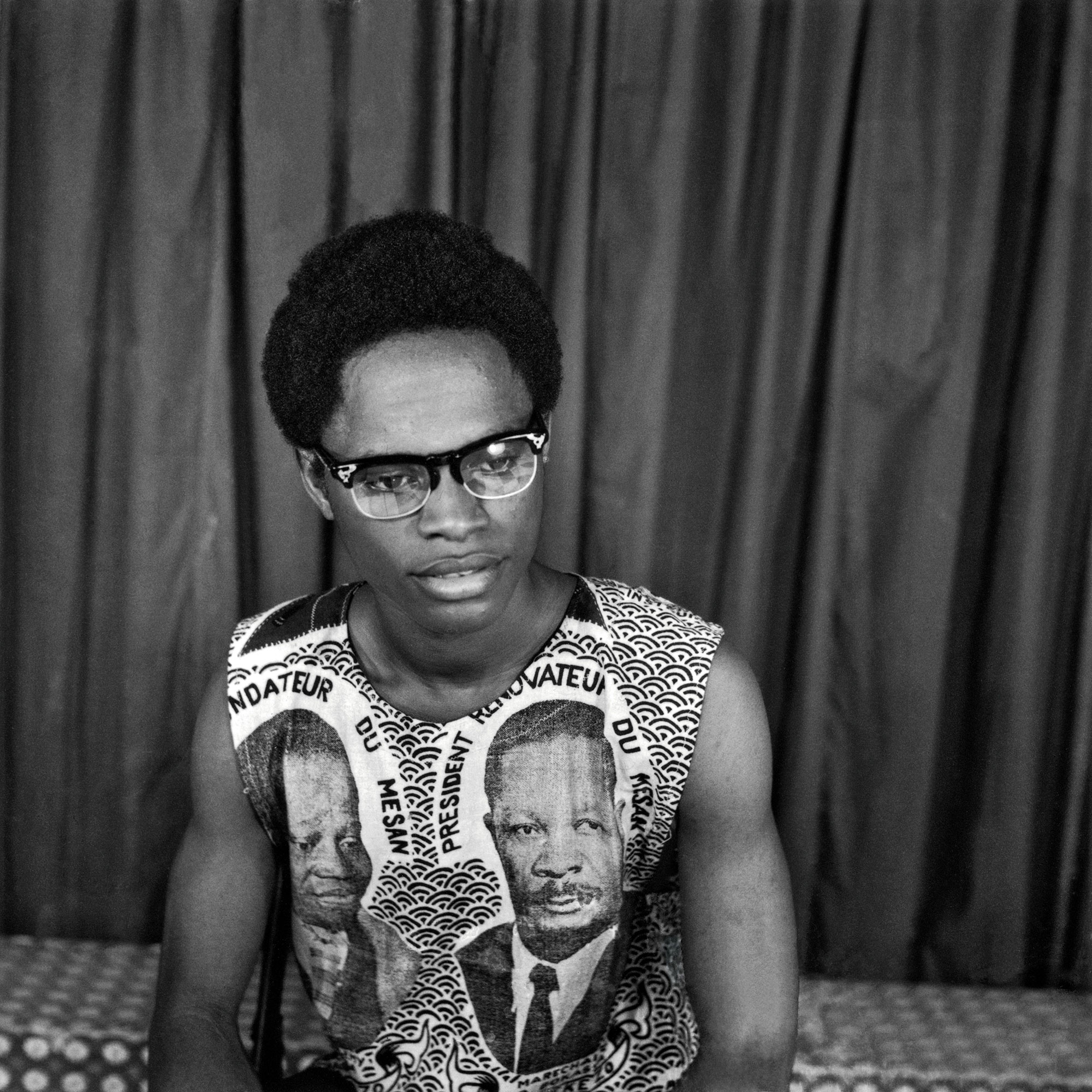

Fosso: I first knew that I had become a photographer when I finished my training, while I was pursuing street photography, and started working independently in my studio. In Africa we say to become a real photographer you have to take the picture and then make the print yourself; that’s how you establish your professional credentials. I made pictures for myself only after the studio closed at the end of the day, using whatever unused film was left over in the roll of twelve exposures to make photographs of myself. My primary motivation for these self-portraits was to create images I could send to my grandmother, who was missing me a lot. Sometimes when I made photographs that I was not satisfied with, where I didn’t feel beautiful inside, I would cut up the negatives instead of printing them. But if I felt that the image was beautiful or represented how I felt inside, then I would print the image and keep the negative. I had a box reserved where I would store such important and special negatives.

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

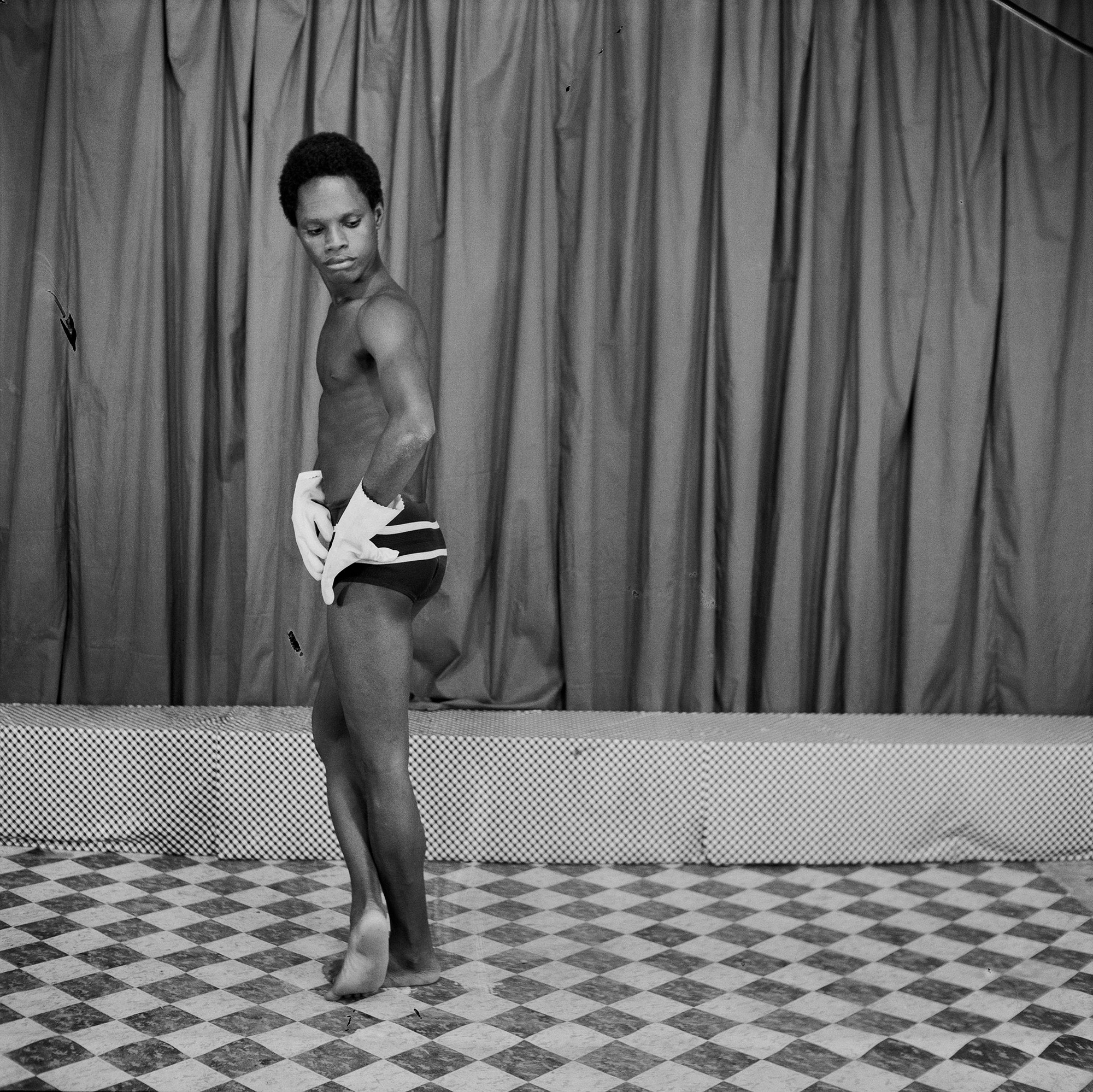

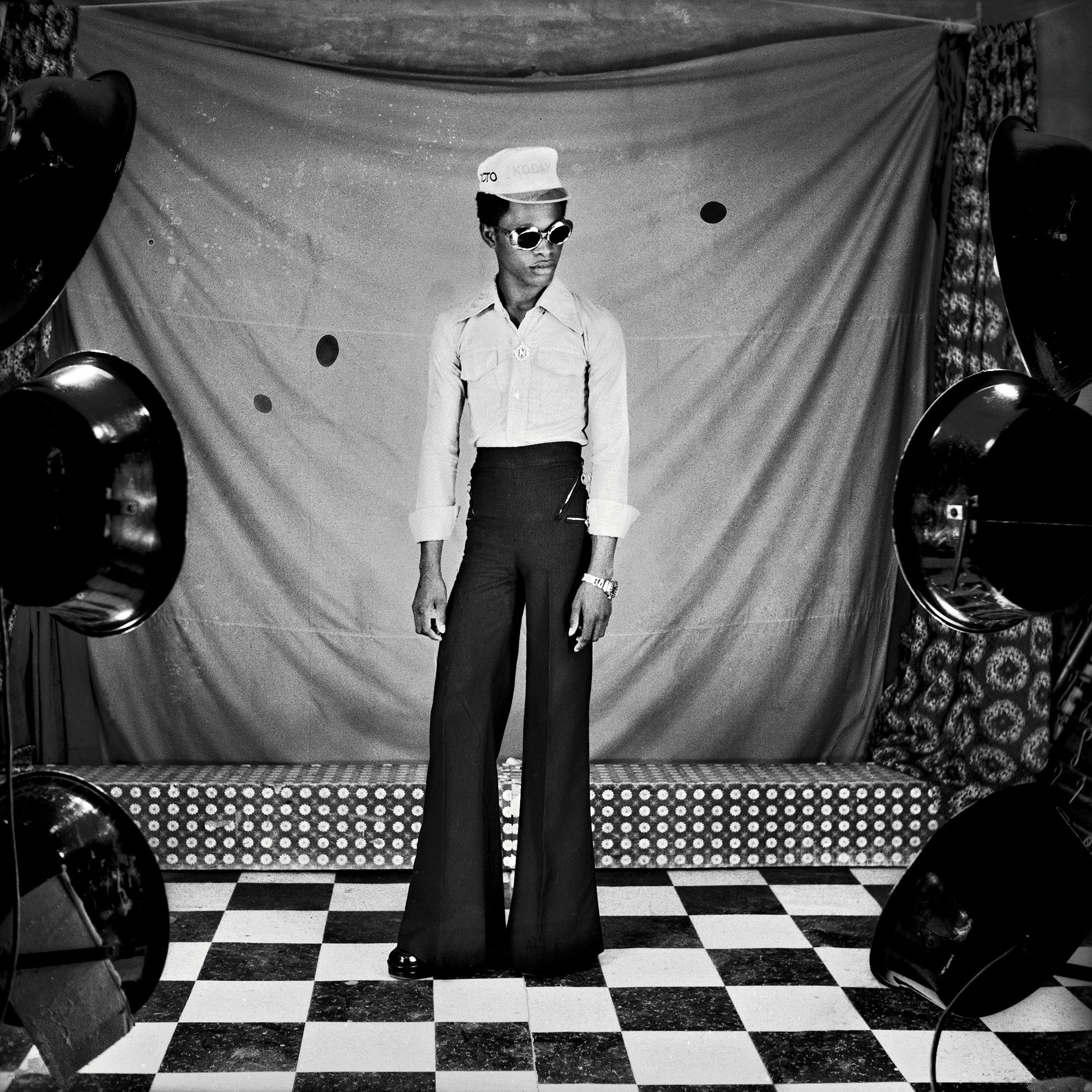

Enwezor: Your relationship to photography has something much deeper, a more personal motivation. From the start it was autobiographical; it had to do with the conditions of your life and how to document that life as it was being transformed. But what you are very well known for are photographic images in which your studio became a theater, a liberated space where you played with codes of representation of gender, sexuality, masculinity, and fashion. This liberated space that was your studio produced some of the most unique and singular examples of studio practice, and I am here thinking of artists such as John Coplans, Pierre Molinier, Van Leo, Cindy Sherman, Yasumasa Morimura, and others who had also made themselves their own subjects. But in your case, you were not so much making self-portraits as you were invested in working with invented characters, with you as an avatar. This is perhaps why your work has been compared most often with that of Sherman. Can you talk about this aspect of your photographic output?

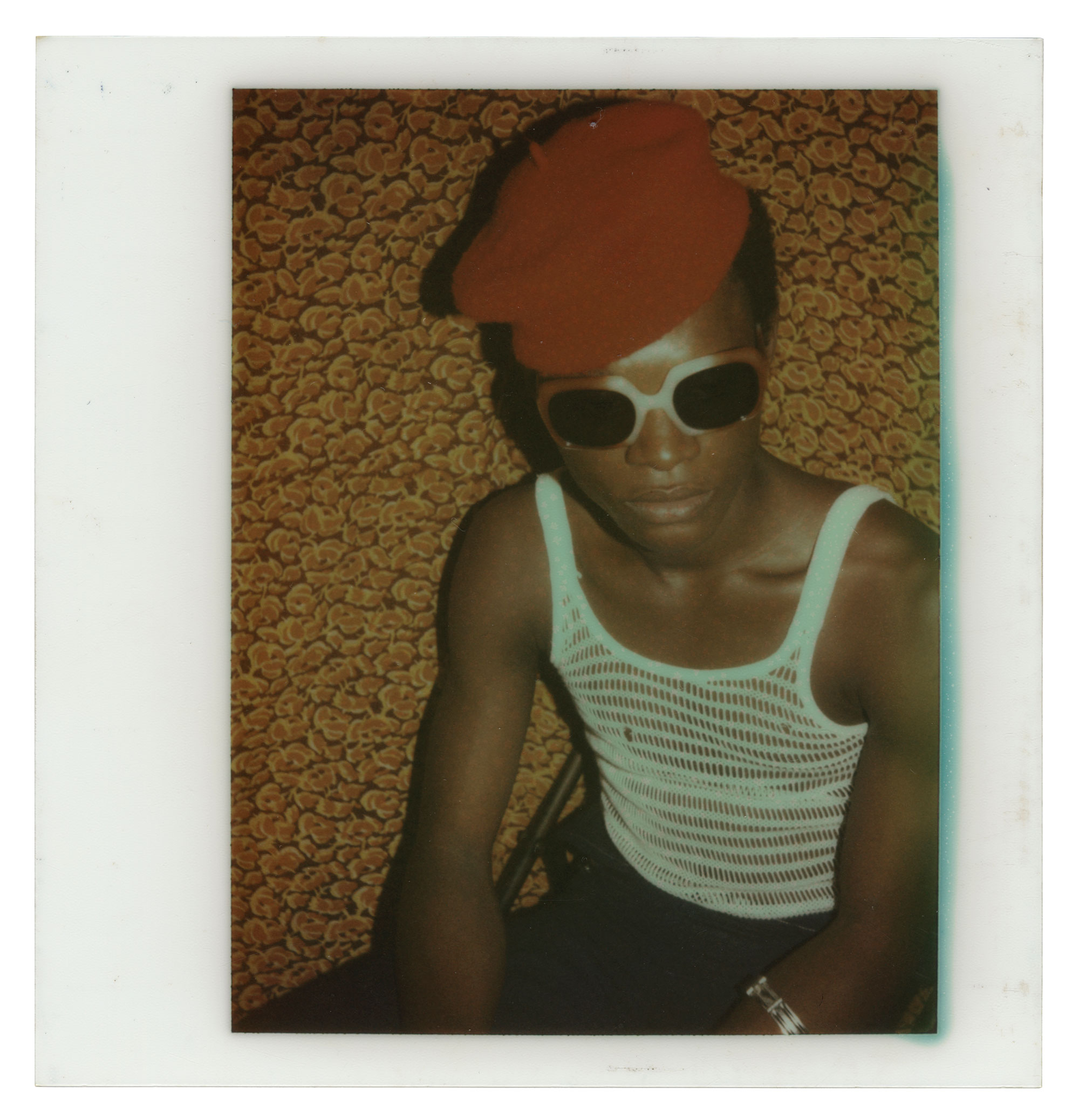

Fosso: My initial encounter with photographic images outside of the Central African Republic was purely through pictures in magazines, brought by young American Peace Corps volunteers who came to the Central African Republic to visit Pygmies. I was especially excited by the images of African Americans and their sense of style.

I was also very much taken with the style of the popular singer and musician Prince Nico Mbarga, who was very hot around West Africa in 1976 and 1977 with his hit record Sweet Mother. I wanted to replicate these two stylistic approaches in the studio with me posing as a model. To do so, I went to the market and bought different fabrics and commissioned a tailor to make outfits for me, which I then used in the studio. Those are the photographs that I became known for.

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: How long did you make work in this vein, documenting yourself?

Fosso: From 1975 to 1990.

Enwezor: If initially you saw yourself as only an image-maker, when did it occur to you that you had become an artist?

Fosso: It was at the first Rencontres de Bamako in 1994 that it became clear to me.

Enwezor: Did this realization change your approach and attitude toward photography?

Fosso: Yes.

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: What changed?

Fosso: I first realized that I was an artist when I found out that my main task was to create. I then said to myself that if what I had been doing as a job was art, why not continue to create regardless of whether I had clients or not? But I was confronted with a financial problem, of how to reconcile my job and creativity. I did not have the financial means, so the question was how I could continue—because had the talent, and I could do more. Fortunately, I was contacted by Tati, the French department store, for a project with Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé. That was a lucky break.

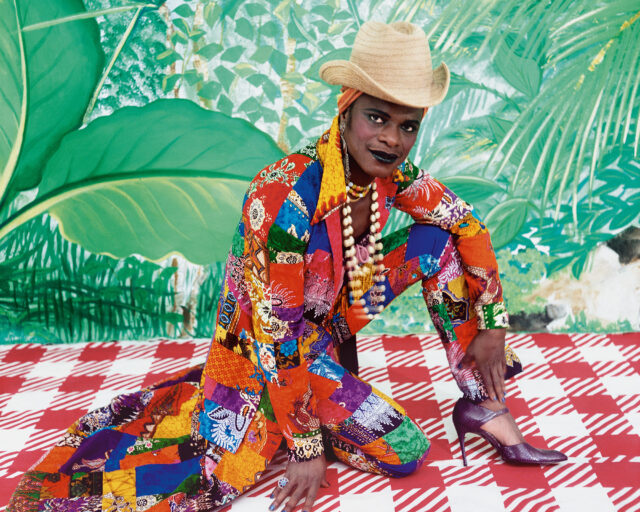

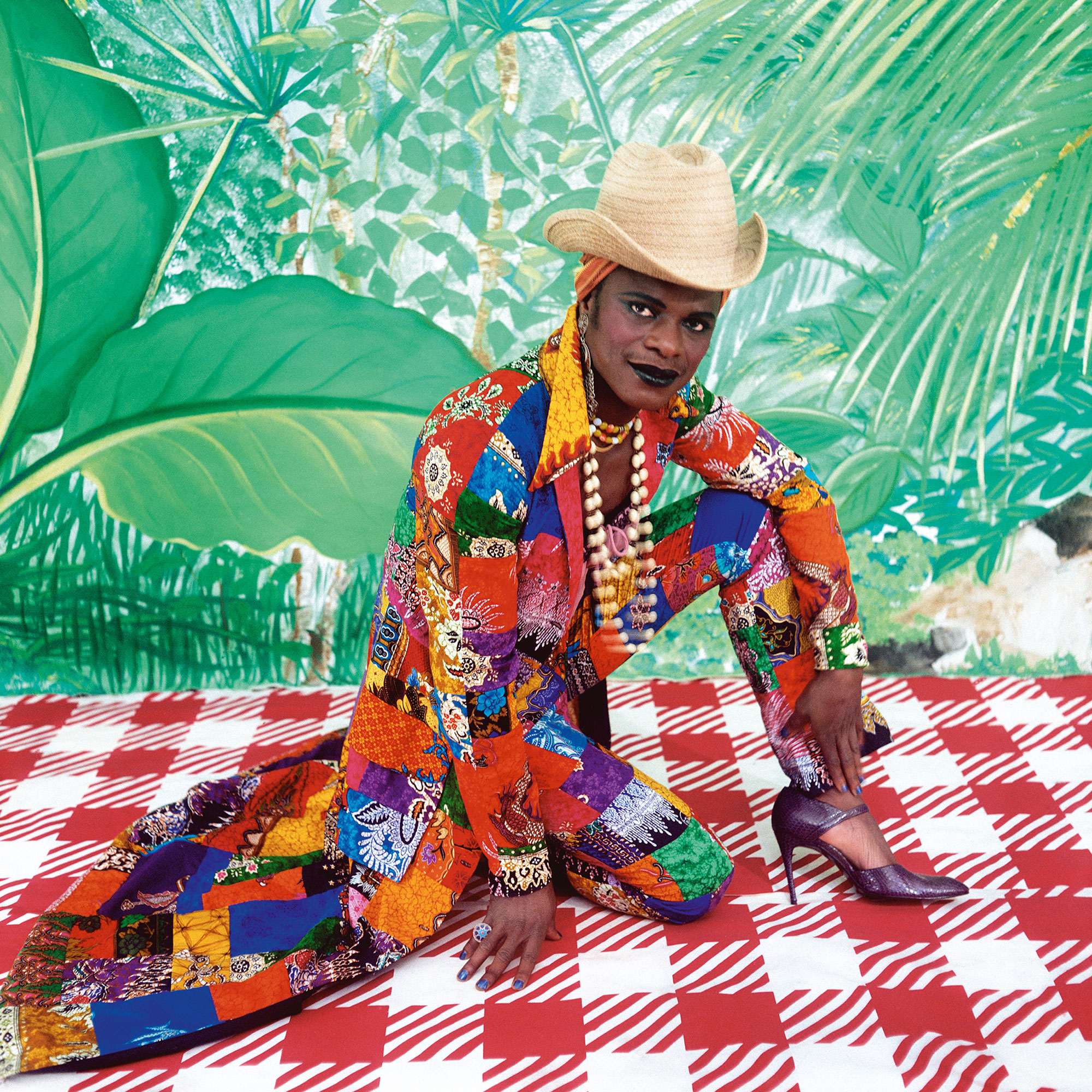

I went to Paris to work on the project. It transpired that Sidibé had already been to Paris, finished his commission, and left for the U.S. for a book signing. However, when I arrived, I learned that the people at Tati had invited us to re-create the African photo-studio environment and make black-and-white pictures. I was not satisfied with this approach, so I asked Tati’s director of photography if it would be possible to work in color. He wondered why, since I had never worked in color, I would want to do so now. That’s how my Tati series (1997) began, because I did not want to go back to the black-and-white style as Keïta and Sidibé had done for their Tati commissions. Since there were three African photographers, I wanted my project to register a different mood of the African imagination, and not the images that were already associated with African photography. My goal was to take a new direction in my work.

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: Although the Tati series was initially a commercial commission, you used it as a springboard into contemporary art.

Fosso: After I finished the Tati project, I returned to Bangui. In 2000, Afrique en Créations financed me to initiate a workshop with two artists from Cameroon, two from the Central African Republic, one from Italy, and one from France. The workshop took place in the eastern part of the country on the border with Cameroon. The project I produced was called Mémoire d’un ami (Memory of a Friend, 2000). In 2004, the Prince Claus Fund financed my next project, Le rêve de mon grandpère (My Grandfather’s Dream, 2003). I went to my village in Nigeria to work on that and presented it in Barcelona the same year.

Enwezor: I want to turn to your process, which, in the work you have presented over the last three decades, has focused on what I could call the “structure of self-representation,” with you playing a role or dramatizing historical, gendered, and autobiographical characters. Over the years, these roles and characters have become more elaborate, more theatrical. Your working method has become more of a big production, with sets, props, makeup, assistants, and lighting technicians, like in a film production. The simplicity of your earlier studio approach, when you worked alone, has largely disappeared from your present mode of making images. In fact, the work is no longer about single self-portraits, but about an ensemble of portraits with diverse psychological and emotional attributes carved into their construction. Can you discuss how you decide on the concept of each series you embark on as you begin planning it?

Fosso: The Tati series was also theatrical and less simple, so my approach was already changing and different from the earlier works of the 1970s.

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: It’s obvious you want to question representations of African masculinity, but also to break certain normative codes of studio photography that are read reductively within the discourse of African modernity. Your work calls all of these assumptions about African representation into doubt. One of the things that has been constant in your practice is your interest in transgression.

Fosso: I recently did an interview, and the interviewer asked me if I have a fear of the politics of Africa. I said I did. However, when it comes to what you call transgression, it was never about responding negatively against someone or against certain ideas. Maybe you are saying that I am not afraid to do what is seemingly not possible to do. But no, that’s not my motivation when I am working. All I will tell you is that my different approach started with my self-portraits, which gave me the opportunity to do whatever I wanted to do.

Enwezor: So, more than merely reflecting yourself—the artist/ego, if you will—the main impetus for your self-portraits was staging a series of ideal selves, situations, and guises in your self-constituted theater of postcolonial identity. There is hardly any kind of sustained photographic focus in contemporary African photography like the one you initiated in 1975. One would have to go back to the 1930s and ʼ40s self-portraits of Van Leo, the Egyptian Armenian photographer in Cairo, for a comparison. It’s quite an achievement for a thirteen-year-old to initiate such a complex study of urban African identity and male desire.

Fosso: I did not know I was making art photography. What I did know was that I was transforming myself into what I wanted to become. I was living out a series of ideas about myself. These images also extend beyond photography. Making them gave me the opportunity to engage in my own biography: going back to when I was a child, when no one thought I was a desirable child to photograph. At the same time, I discovered images of contemporary events in South Africa and the plight of black people in America. All these things contributed to shaping my lens. Art photography was something completely foreign to me until I arrived in Bamako for the first Rencontres Africaines de la Photographie.

Secondly, it became an opportunity for me to profit from the experience and therefore continue doing what I wanted to do. The invitation by Tati in 1997 to develop new work for their fiftieth-anniversary celebration the following year was an extension of what I had been doing in my studio since 1975. When I aspire to create new images, I try to develop the work in such a way that it will be in direct communication with the viewer. My approach is to produce pictures with as little ambiguity as possible, even when they might seem ambiguous. For example, when I adopt the image of a woman in my photographs, I am by no means trying to create a queer picture. What you see is simply an image of a man in women’s clothing. It is not about creating a double meaning.

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: In your work, the studio becomes a sort of theater of fantasy, as well as a space for the mediation of history and social identity. Given the fact that the roles you enact before the camera are multiple, what roles do you see these various guises or personae playing in your overall conception and construction of the image?

Fosso: While all the series I have done can be understood by viewers as discrete and self-contained, and therefore different, to me there is one unifying theme behind all of them—and that is the question of power. I am particularly interested in the role that slavery played in the history of Africa. If I am representing the image of an African chief (in Igbo we call them “Eze” or “Igwe”), I am thinking about power, but also the role of those chiefs in the slave trade. In the case of “African Spirits,” this becomes much more transparent. This, for me, is the red thread, in either an obvious or subliminal way. I want to show the black man’s relationship to the power that oppresses him.

Enwezor: One of the challenges for African artists of your generation today is the state of their archives. Since much of your work was destroyed during the recent conflict in the Central African Republic, have you given any thought to the state of your own archive?

Fosso: This is a very big issue for many photographers and artists in Africa today. My dream is to bring my work and archive back to Nigeria and give it to a museum in Ebonyi State, where my family comes from.

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: When you look back at your career, having survived a brutal civil war in Nigeria as a young boy, then beginning in 1975 with Studio Photo National, to today, where your photographs are being collected by museums and private collectors, and being exhibited across the world, would it be safe to say that your work has given you a passport to travel the world both physically and imaginatively?

Fosso: All I can say to you is that since starting my career as a young boy in 1975, my choice to become a photographer has been a positive contribution.

This conversation is adapted from Samuel Fosso: Autoportrait (Steidl/The Walther Collection, August 2020).