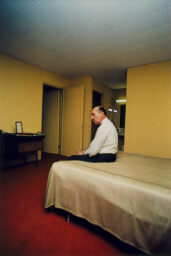

With a once-in-a-generation election on the horizon, Aperture spoke with photographer Judith Joy Ross, whose series Portraits of the United States Congress, 1986-87 is currently on view at Tops Gallery in Memphis. Here, Ross reflects on photographing the men and women at the height of American leadership. —Emma Kennedy

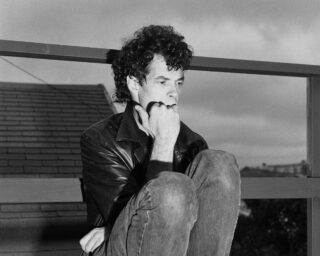

Courtesy the artist

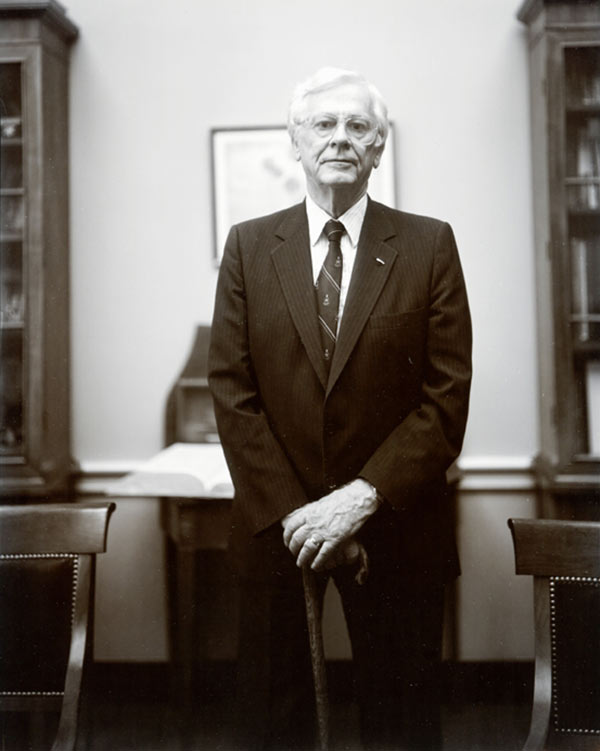

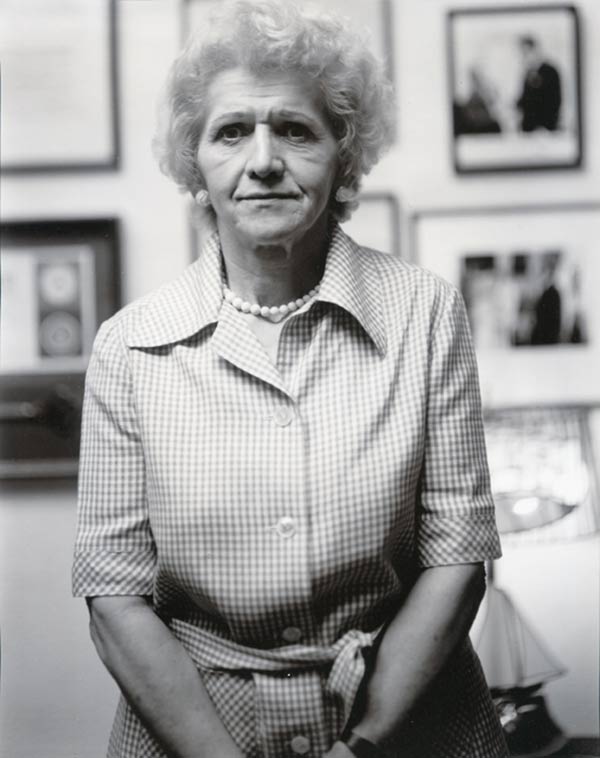

Aperture: You made Portraits of the United States Congress, 1986–87 ten years after Richard Avedon’s The Family, a project about American leaders in politics, finance, and media, originally commissioned by Rolling Stone for the United States Bicentennial. But, unlike Avedon’s forensic treatment of figures such as Rose Kennedy and Ronald Reagan, your series is more intimate and sensitive, while being no less authoritative. Did you have Avedon in mind when you made this project?

Judith Joy Ross: I bet you could never guess that it was the work by the great photographers Southworth and Hawes that compelled me to make Portraits of the United States Congress, 1986–87. I owned a book The Spirit of Fact: The Daguerreotypes of Southworth and Hawes, 1843–1862 (1976), by Robert Sobieszek and Odette Appel, published by Robert Godine. The overwhelming power and nobility of those faces, especially the portraits of Lemuel Shaw, was my guide to making congressional portraits.

The only thing I ever thought about Avedon is rather embarrassing: How come my pictures are not as renowned? But, I figured an Avedon portrait is like a magnificent and very costly arrangement of flowers. My work is like a backyard garden or wildflowers at the side of a road. One way isn’t better than another, just different. Avedon makes his subjects important with his form and style. I am more interested in our ordinariness, our flaws and strengths.

Courtesy the artist

I made Portraits of the United States Congress, 1986–87 to deal with authority figures on my own terms. 1986 was the time of the Iran-Contra Affair. Ronald Reagan was President. Tip O’Neil was Speaker of the House. Congressional figures, just like today, promoted themselves with offensively banal photos. When I was photographing at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 1983–84, the Capitol was visible in the distance. I wanted to know who these people were who were in our government, the people who were running our lives. They didn’t look real to me in the media except for on the MacNeil/Lehrer show (now PBS NewsHour), where the masks were off.

Courtesy the artist

Aperture: Could you tell us about your sessions with the Congresspeople? How did you describe your intentions to the politicians, and why do you think they agreed to be photographed?

Ross: I contacted the appropriate staff of the Senator or Congressman or Congresswoman who I wanted to photograph, and I requested an opportunity to photograph them in their office during a fifteen-minute appointment. I stated that their subsequent portrait would be exhibited during the Bicentennial of the U.S. Constitution at America’s oldest art museum, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. That’s all I had to offer them—a little bit of patriotic publicity. I had arranged an exhibition before I made the pictures. A very nervy thing.

I figured out who to photograph with the help of the wonderful Almanac of American Politics published by the National Journal. It is a 1,591-page compendium of information about the Members of the House and the Senate. There are tiny pictures of each member of the House and the Senate, with detailed informoation on how exactly they voted and who they represent. I picked people I disagreed with and people I agreed with. This was very inspiring.

Courtesy the artist

During the year I worked on this, I would spend one week arranging for appointments from my home in Allentown, Pennsylvania. (This was back in the day of typewriters and telephones with push buttons.) It was very nerve-wracking. I am a very disorganized person, so this was an immense challenge. The alternate week I went to D.C. to shoot.

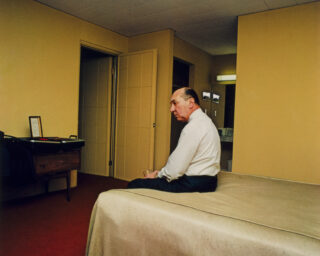

I shot in available light with an 8-by-10 view camera. I used film designed for copy negatives, which gave me more ability to shoot in terrible light. I set up the camera in five minutes. I had ten minutes to shoot and leave. It could take an hour or more to get from one appointment to another through all the halls of the House or the Senate. There was a lot of waiting, worrying, fear and excitement at wandering those halls, dragging my heavy equipment. When I finally met the Congressperson, sure I was scared, but I was invested in making it work. Finally it was my time! Time to see. Time to discover what was to be seen. Time to make a portrait!

Courtesy the artist

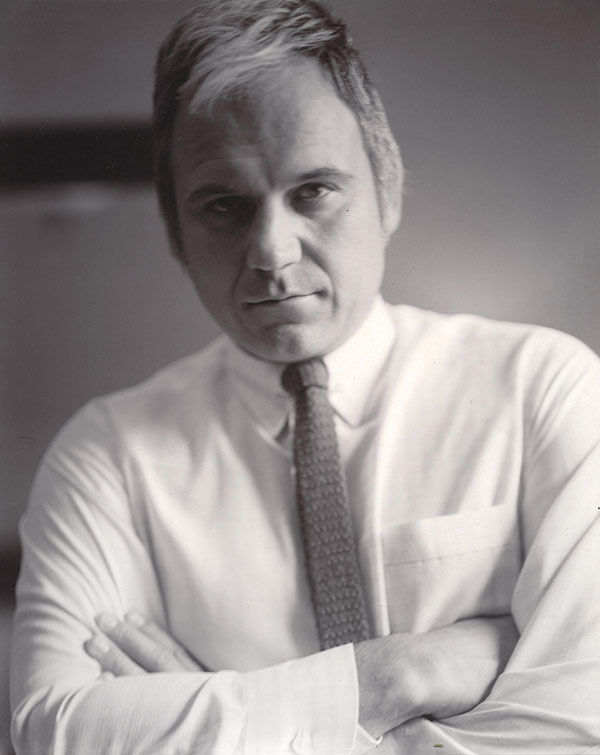

Aperture: Why did you decide to make classical portraits, with minimal, almost generic context provided by their office settings, instead of, say, images of Congresspeople at work in the chambers or on the campaign trail?

Ross: I did not have any idea I was making “classical portraits,” but I can see what you mean. They are, to me, the kind of pictures that someone who loves Eugène Atget and August Sander as much as I do would likely make.

These pictures are made in the offices of each Congressperson. A place that could not be more intimate. Did I have to include what kind of decor to know who they were? I decided absolutely not. The person was the subject and getting as much of them as possible in the picture was the goal, a huge challenge in low room light.

Also, consider that when you use an 8-by-10 camera, there is so shallow a depth of field with a normal lens, which I used, that you have to eliminate environment unless you back up and make a three-quarters or full-length figure. The congressional office environments were telling, but something has to be sacrificed when you make a picture. In my preceding body of work, Portraits at The Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Washington, D.C. 1983–84, only rarely is the Vietnam memorial seen. The memorial is in the faces of those depicted.

Courtesy the artist

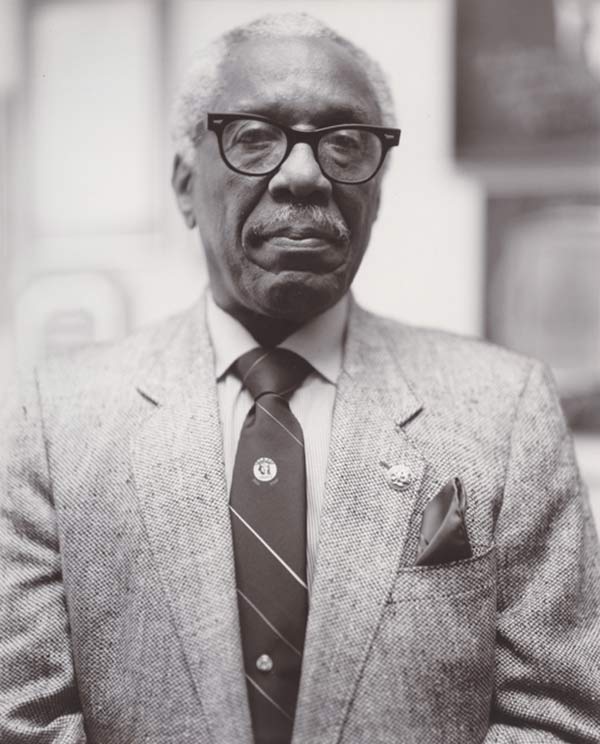

Aperture: Photography might be a great equalizer, but that doesn’t mean formal portraiture can automatically instill empathy. You’ve said that you made this series in part to “confront” your prejudices. Does your formal portraiture of Congresspeople invite us to imagine perspectives that might be at odds with our own convictions and opinions? And, in the divisive, seemingly intractable negativity of the current election season, what can your portraits tell us about our past—and our future?

Ross: Susan Kismaric states in her admirable book, American Politicians, Photographs from 1843 to 1993 (1994), “Ross had gone to Washington with mix of emotions—hoping that the camera would objectify her subjects and in turn identify some truths about them, and simultaneously wishing that her previously held ideas about who was ‘good’ and who was ‘evil’ would be confirmed. To her surprise, instead of an either/or record of good or evil, she came away with a series of portraits of very human beings. Her subjects appear to suffer the same complicated lives we all do.” Was I always fair or accurate? No I wasn’t. This is a group portrait of us as a nation, including that fact that we are squired in favor of white male representation.

Courtesy the artist

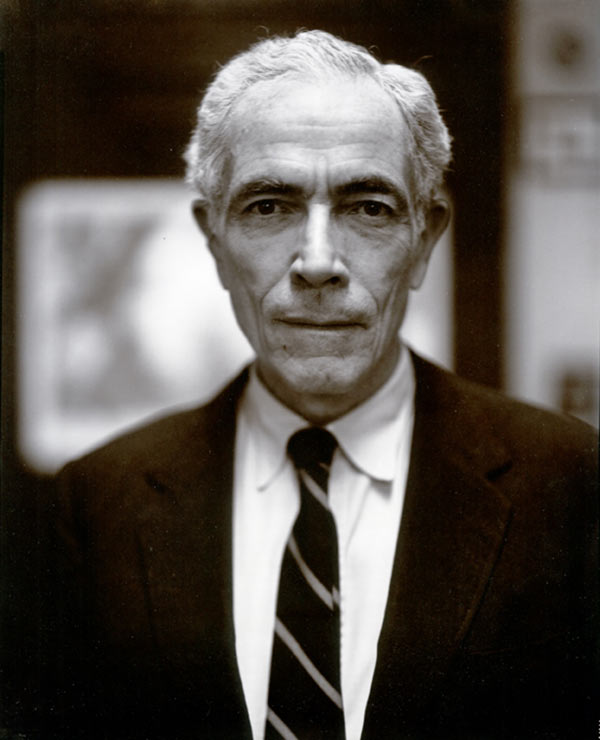

Aperture: Several of the elected officials you photographed, notably Strom Thurmond and Robert C. Byrd, remain controversial for their outspoken resistance to civil rights. How do your images—and the new exhibition—engage this history?

Ross: I am more often than not horrified by the beliefs and actions of others, as we all are on both sides of a position. But this is the deal we have. We are flawed. We can do great things and absolutely horrendous things. And we do not agree on what those things are. Back in the day, when I made these pictures, compromises were made in the Congress. It’s how government works; I don’t have to tell you.

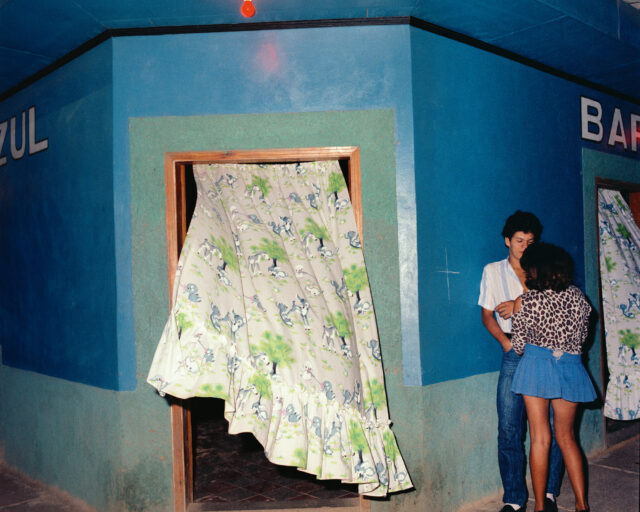

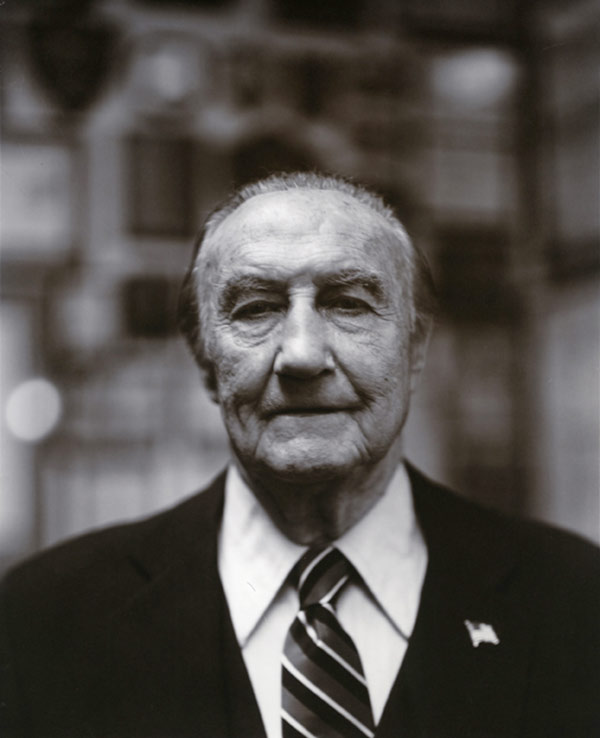

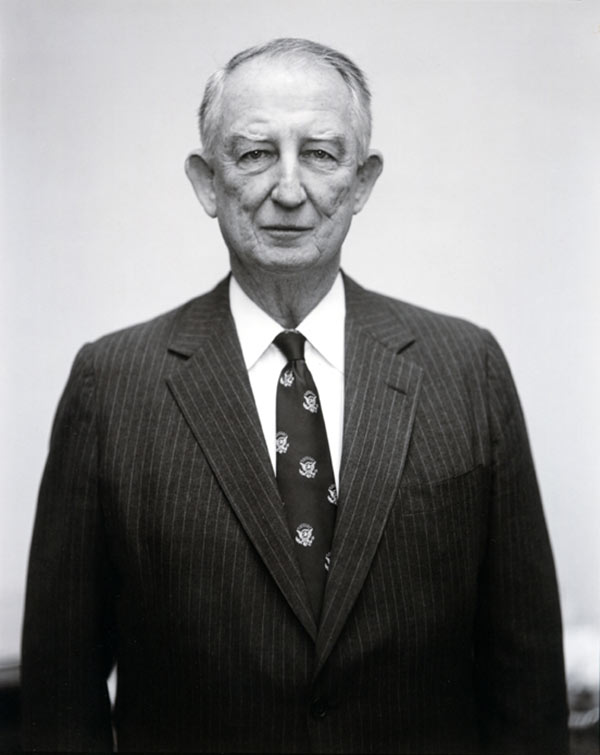

As for Strom Thurmond, I utterly disagreed with him. So what. Here is a man with charisma, and he looked like he could have been a king. He even had what I assumed was Louis XIV furniture in his office. Does he not have that presence here with his enormous shoulders and tiny apple-shrunken head and gleam in his eye, a force to be dealt with and yet….

Courtesy the artist

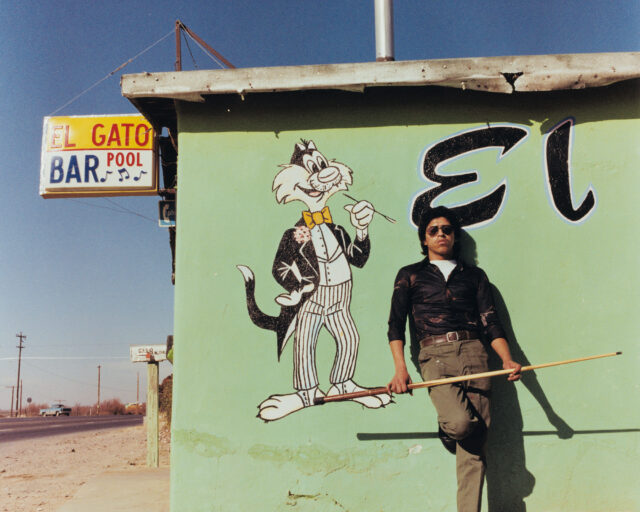

With Senator Byrd, his power also was overwhelming but strange. Yes, sadly at one time he was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. Years later Senator Byrd gave the best and only speech against the Iran–Iraq war. But I do not care about who I disagree with or not. It’s not an issue. Take a look at Senator William Roth. He was powerful and friendly; he looks like Walter Matthau. How about Senator Claiborne Pell. I thought he looked like the Buddha. He told me he was exhausted. I got so close to him because he was so astonishingly calm and beautiful. But I cannot talk about them all.

Courtesy the artist

I did my research, I had my opinion, and then I made discoveries. I believe it could be a truth that you are looking at in these portraits. But, perhaps you would like to know that there was one figure I disliked above all and from whom I walked away from a shoot appointment. I had an appointment to shoot Senator Jesse Helms. And it turned out this shoot was going to be on the Capitol steps, immediately after he was photographed with a high school group. I had my tripod and camera lying in the grass and trees below the Senate side of the Capitol at the right time I was to go up and photograph him. (I imagine I would have been shot by a sniper for such a thing today.) Anyway I walked off … just took my equipment and left. I was content not to make his portrait and to continue to demonize him in my mind. Yet, was I terrified of the responsibility and the incredible opportunity to deal with this site. I don’t know. I just continue to say to myself, I like that I walked away, because it gives me touch of self-righteousness I crave. Whereas the picture I might have made could perhaps have given a more complex and useful result.

Courtesy the artist

Aperture: How do you feel about exhibiting this series again, three decades later?

Ross: I am so pleased with the opportunity to get this work back out there in this politically charged and distressing time. Can these pictures tell us about our future? I can only tell you about me, and I am, as of this writing, terrified.

Emma Kennedy is a work scholar at Aperture magazine.

Portraits of the United States Congress, 1986–87 is on view at Tops Gallery, Memphis, through December 3, 2016.