The PhotoBook Review’s Publisher Profile

Willem van Zoetendaal did not become a photobook publisher out of a sense of vocation. Many of the activities that form an integral part of publishing are anathema to him. Cost balancing? Zoetendaal shrugs. If he feels the urge to bring out a book under his imprint, Van Zoetendaal Publishers, then that’s exactly what he does, even if the financing is not yet in place. Van Zoetendaal selected five books from his collection that, together, as told to Arjen Ribbens, tell the story of his publishing house. This excerpt comes from the latest issue of The Photobook Review.

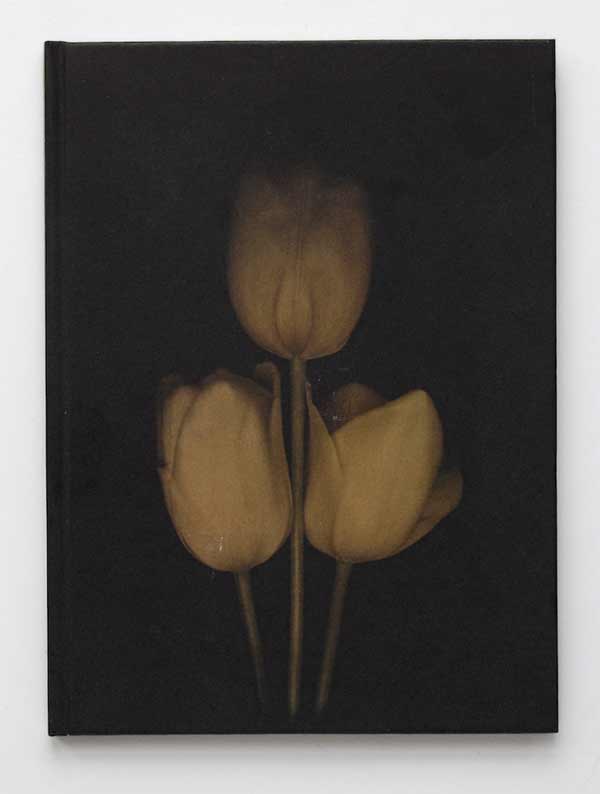

Tulipa, L. Blok and Jasper Wiedeman, Basalt, Amsterdam, 1994

Tulipa

L. Blok and Jasper Wiedeman

Basalt • Amsterdam, 1994

This was the first book that I published myself. I set up a foundation, Basalt, for this purpose, together with the art historian Frido Troost (1960–2013), so that we could apply for grants. Why the name Basalt? Because I was born at The Hague’s breakwater. This is the first in a series of books in which I juxtaposed historical and contemporary photography. In this case, it was autochromes from the 1920s by Leendert Blok, a photographer who worked for flower bulb cultivators in the Netherlands’ Bollenstreek region, and photographs by Jasper Wiedeman, who had just graduated from the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, where I was teaching at the time. By contrasting the two, you get differing perspectives. Contemporary photography can open a new window on history. I had the good fortune that there were a lot of students at the academy back then who felt connected to traditional photography. Many of them went on to achieve international renown, including Céline van Balen, Rineke Dijkstra, Hellen van Meene, Paul Kooiker, and Koos Breukel.

To Sang Fotostudio, Lee To Sang, Basalt, Amsterdam, 1995

To Sang Fotostudio

Lee To Sang

Basalt • Amsterdam, 1995

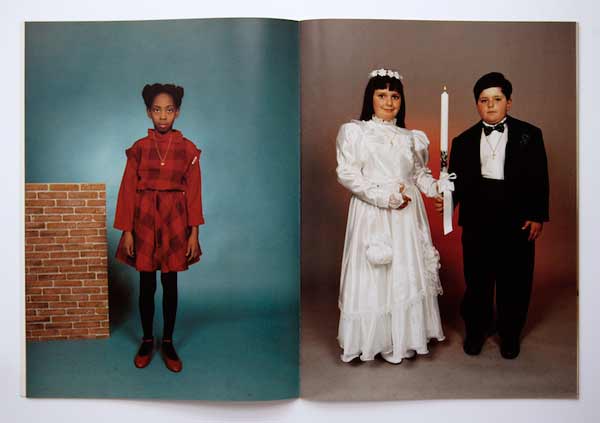

One day in the early 1990s, I passed a photography studio called To Sang Fotostudio in Albert Cuypstraat, Amsterdam. In the window, I saw a photograph of a fellow journalist with his daughter on his lap. The photographs in the window provided such a beautiful record of this colorful, largely immigrant neighborhood, that I gave my first- and second-year students money to go and get their portraits taken here. In 1995, I published a large-format folder of twenty-three portraits by the studio’s photographer, Lee To Sang. The design is entirely subordinate to the image. But the book works. Frido Troost and I put a lot of work into the picture editing. This publication made quite a stir: an exhibition about To Sang Fotostudio traveled to various photography festivals, Tate Modern acquired a number of the photographs, and Johan van der Keuken made a documentary about To Sang. His photography studio became a cult success. Martin Parr is one of many significant figures who went there to have their portraits taken. After he retired, Lee To Sang gifted me his archive—some seventy thousand negatives. So it is still a resource for publications to this day.

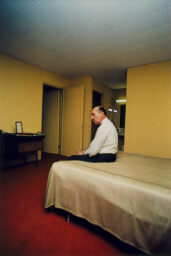

Quatorze Juillet, Johan van der Keuken, Van Zoetendaal Publishers, Amsterdam, 2010

Quatorze Juillet

Johan van der Keuken

Van Zoetendaal Publishers • Amsterdam, 2010

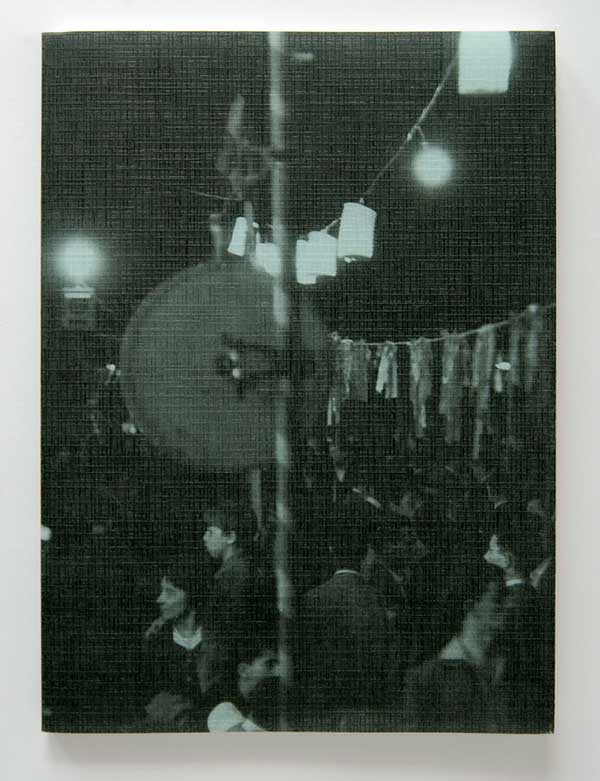

In Johan van der Keuken’s archives, I found thirty-three photographs of people partying in the streets of Paris. They were all made on July 14, 1958, the country’s national holiday. I arranged the photographs in such a way that they also form a dance. I love slim editions, so I use the negative format less and less—4-by-5 inches, for example, leads to a bulky format for a book. Over the years, I’ve moved away from using stiff paper. This book is printed on paper from Gmund, a German manufacturer whose products I love. It’s fine, uncoated paper: if you don’t want the pictures to show through it, you can only print on one side. So the pages have Japanese folds and are bonded with cold adhesive. There aren’t many pages, but the folded leaves give it a good volume. The cold adhesive binding allows the book to be unfolded easily.

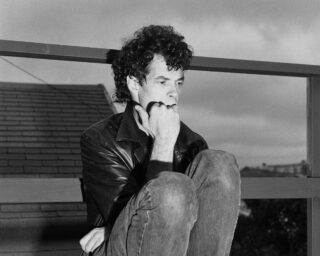

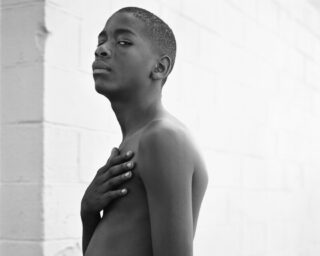

Arthropoda, Harold Strak, Van Zoetendaal Publishers, Amsterdam, 2011

Arthropoda

Harold Strak

Van Zoetendaal Publishers • Amsterdam, 2011

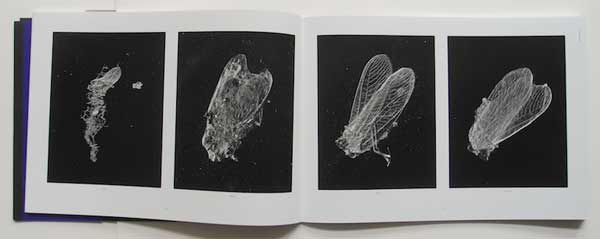

Harold Strak is a photographer who has an almost scientific approach to his work. This book contains eighty photographs of the remains of insects that were ejected from spider webs after they were eaten. I chose a rectangular format so that I could show four photographs side by side on each double page spread. The lithography and printing technique were inspired by Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco. Their publication Seeing Things (1995), about the history of photography, is one of the most beautifully produced books I know: superior printing in eighty-eight colors, with each print run dried for twenty-four hours. I went to the same lithographer, Robert J. Hennessey, who also lithographs all the catalogues for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Massimo Tonolli, a top Italian printer from Verona, printed it beautifully in tritone.

Mädchen, Diana Scherer, Van Zoetendaal Publishers, Amsterdam, 2014

Mädchen

Diana Scherer

Van Zoetendaal Publishers • Amsterdam, 2014

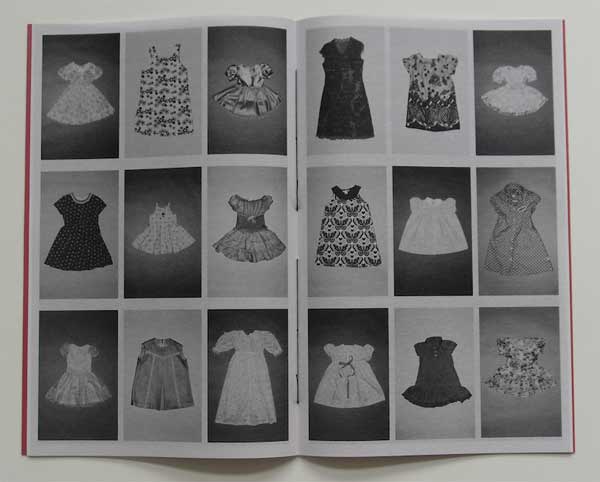

I’m always present when a book is printed. It was especially important in this case. I like black to be really black, and printers don’t often print it to my liking. I had the cover of this book run through the press one more time in order to achieve the deep black. I made it this big (9 ½ by 15 inches) so that it would become a physical experience. I used two types of paper for the inside; the Japanese paper feels a little bit like the dresses in the photographs. No, there is no text in this book. An introduction would undermine the mystery. In my books, you never find texts about the photographs themselves. You can’t explain photographs. The magic of photography is precisely that you study images yourself and give them your own meaning.

Willem van Zoetendaal is the designer and editor of seventy photography books to date, many of which he published under his own imprint, Van Zoetendaal Publishers. Van Zoetendaal has also curated numerous photography exhibitions in Italy, France, Spain, the Netherlands, South Korea, and Japan, and ran a contemporary photography gallery under his own name from 2000 to 2014.

Arjen Ribbens is an art editor for NRC Handelsblad, the leading Dutch evening newspaper. He is also a part-time publisher specializing in art editions and books on stupidity (De encyclopedie van de Domheid, or The Encyclopedia of Stupidity, 1999).

Translated from Dutch by Heidi Steffes.