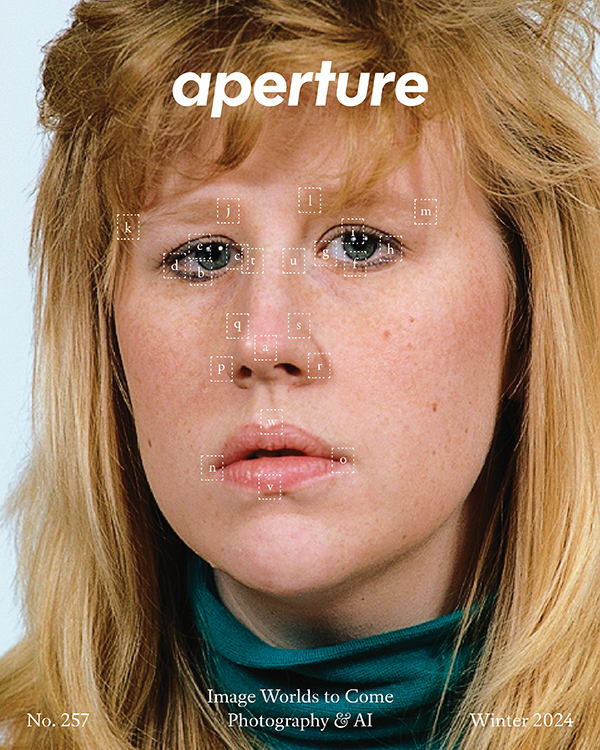

At San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art, a New Frontier for Photography

Snøhetta expansion of the new SFMOMA, opening May 14, 2016 © Henrik Kam. Courtesy SFMOMA

When SFMOMA reopens next month, the new Pritzker Center for Photography will become the largest photography showcase in an American art museum. The center will have double the original gallery space and new, state-of-the-art educational and storage facilities. At the heart of one of the nation’s leading fine art institutions, photography will take center stage. Glen Helfand recently spoke with senior curator Sandra Phillips about the Pritzker Center and upcoming exhibitions at SFMOMA.

Glen Helfand: How much discussion was there about the importance of photography as a medium in terms of its prime location in the museum?

Sandra Phillips: There’s a considerable group of Trustees who are committed to photography. I know that photography was something that SFMOMA director Neal Benezra and the Trustees were eager to present in an important and focused way in the enlarged museum, and it’s something we’ve stood for since the museum was founded in the 1930s. We have been very photography-oriented because it’s been our important community, both historically and now.

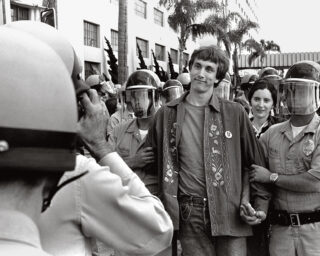

Lewis Baltz, Claremont, 1973 © Estate of Lewis Baltz. Courtesy SFMOMA

Helfand: What exactly is the Pritzker Center for Photography?

Phillips: It comprises the old galleries in the Botta Building that now showcase the permanent collection. It includes the Photography Interpretation Galleries, which will also include a coffee bar. And it includes the Temporary Exhibition galleries for photography, where we will present our own shows and those from other institutions. Finally it will also include the collection itself, the study room, a classroom, and two offices.

Helfand: What aspects are you most excited about?

Phillips: I think the whole thing as a unit, which unites the study of the original objects in the study room with work being shown in the galleries, together with an in-depth concentration on our permanent collection and a creative use of it. It will enable us to bring in more shows from other institutions. We will also be developing our archives and making all that accessible. The whole thing is like a dream come true.

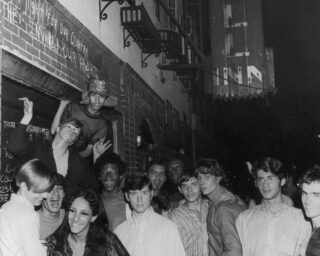

Seiichi Furuya, Izu, 1978, from the series Portrait of Christine, 1978 © Seiichi Furuya. Courtesy SFMOMA

Helfand: What’s in the Photography Interpretive Gallery?

Phillips: There will be exhibits about aspects of the collection presented digitally. In the opening program one will feature examples of California photography in our collection, one of our strengths. It will present a kind of roadmap where you can figure out what pictures of Yosemite or Los Angeles we have. There will also be educational games to help people understand how photography actually works, for instance, a way to make a photogram with your cell phone to understand photographic process and photographic ideas. Then there’s access to other aspects of our collection, like films on and interviews with photographers whose work we own. We just went to Japan and interviewed ten photographers who we will be showing in the second permanent collection exhibition. These will be edited and put up online, and also available in the gallery, so you can see what these photographers have to say about their work when you see the show.

Stephen Shore, Market Street, San Francisco, California, September 4, 1974, 1974 © Stephen Shore. Courtesy SFMOMA

Helfand: What ways do you see the expanded facility shifting what the department can do moving forward?

Phillips: One of our strengths has been to think of ways to present all kinds of photography. I think that’s one of the great aspects of this medium—the technology is available to everyone. We haven’t shown much of our large vernacular collection and it deserves to be seen because it’s so relevant to the questions we ask of photography now. Now that we accept photography fully as art, the vernacular tradition might be rethought and put into the context of so-called “art photography.” I think this is a wonderful way to get people to think about the diversity of the medium, and what it can do uniquely.

Helfand: How many works are in the collection now, and how much activity happened in terms of growing it during the construction hiatus?

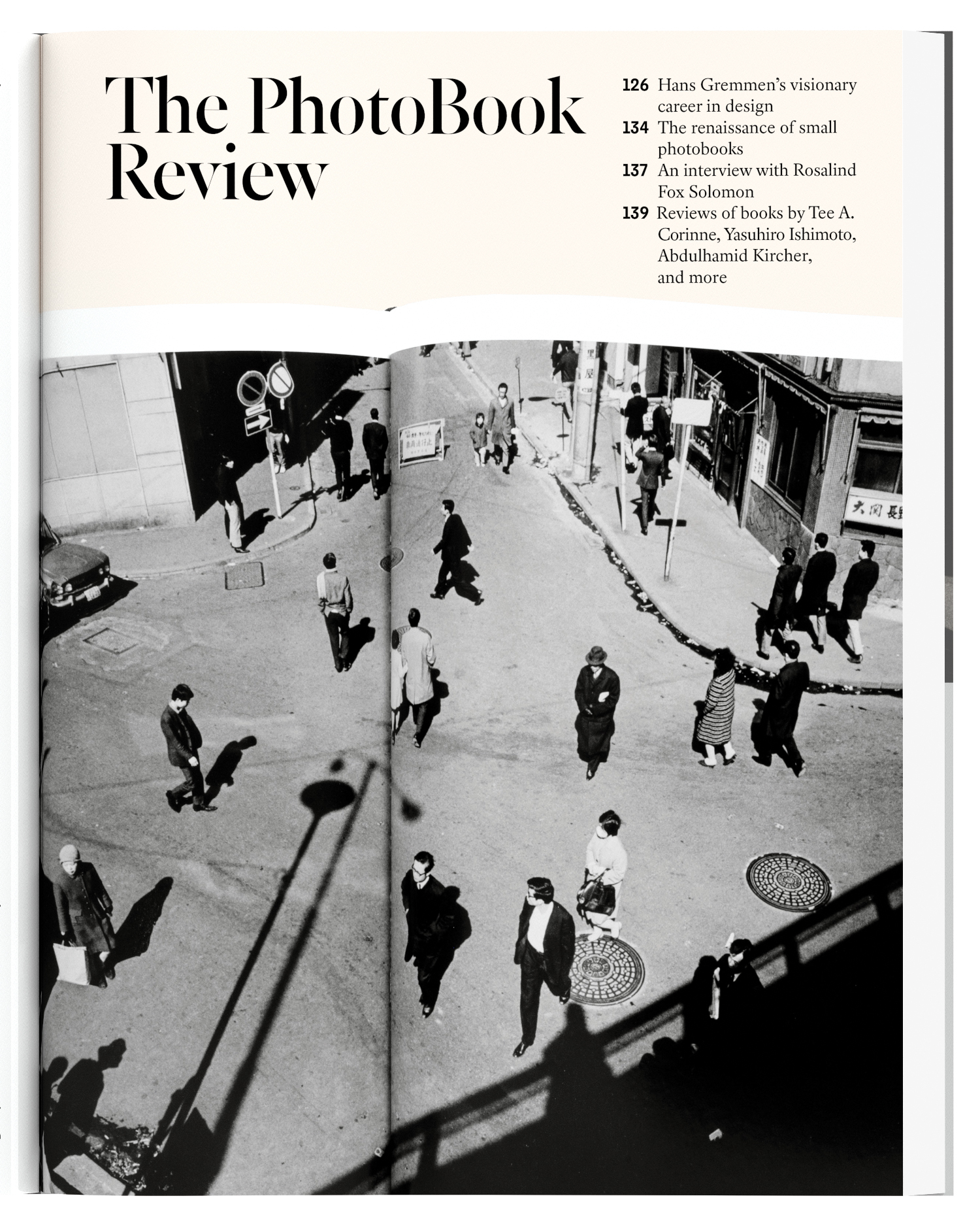

Phillips: Well, there’s something like 18,000 pictures in the collection. During the closure, we got a large and very wonderful group of pictures from Japan, the so-called Kurenboh Collection. I think it’s a very interesting collection, and it really adds to our commitment to Japanese photography, and helps us move forward into the current activity, where there is a vital group of young, important photographers. I think Japan is a very interesting community for photography.

Tseng Kwong Chi, Grand Canyon, Arizona, 1987 © Estate of Tseng Kwong Chi. Courtesy SFMOMA

Helfand: You concentrated on California for your opening exhibition California and the West, which includes mostly recent acquisitions and gifts. Can you talk about the concept of the show?

Phillips: When I did the show called Crossing the Frontier, in 1996, I realized how much amazing material there was that reflected the discovery and development of the West, and what had happened after it was initially developed. It was a show designed to present how we developed Western land for all kinds of purposes, to extract mineral or lumber or whatever, and what we’ve inherited from that. So there will be some of that kind of material in this show as well, but it does not stop there. Since this was a show about the gifts we were receiving, we also wanted to include pictures of the northern California landscape in photographs from people like Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange and Minor White to the present. In California, there’s been a very interesting culture for photography, though it’s not generally recognized as coming from here. That was my stated aim—to discover the tradition and to put it into some kind of context that could be understood, and show how it developed.

Helfand: What are some highlights?

Phillips: There’s some very beautiful early work. Not only Watkins’ pictures of Yosemite, but also early pictures of the developed land. There’s a diptych of a corporate farm in southern California in the nineteenth century. We were also fortunate to receive the beautiful, very important, very modernist surf sequence by Ansel Adams. The show and gift campaign also enabled us to focus attention on photographers of this area associated with the New Topographics exhibition, and to pursue some of the great figures of the 1930s—Weston, Cunningham, Minor White—and add significantly to those holdings. And then we were able to add to the conceptual work that was going on here in the ’70s and ’80s—Bruce Connor, Hal Fisher, Lew Thomas, and finally what’s been happening here more recently with work by Larry Sultan, Mike Light, and Trevor Paglen.

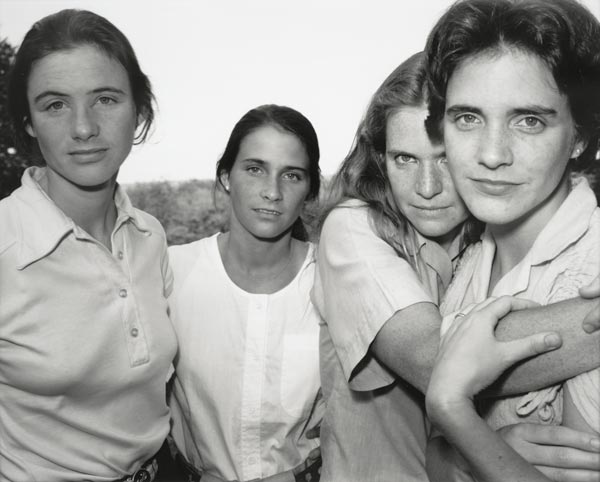

Nicholas Nixon, The Brown Sisters, East Greenwich, Rhode Island, 1980 © Nicholas Nixon. Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Helfand: The California show is in dialogue with the other opening exhibition, About Time.

Phillips: About Time is really a show that considers this element of photography that’s constant to it, and pursuing the ideas that come out of it. The show looks at the whole medium and also examines the implications of these ideas in video and projection. I think it’s a really wonderful and important show.

Helfand: How will you be moving forward with the department?

Phillips: I’m officially retiring at the end of June. I will continue to organize shows that have been on the calendar. The show from our Japanese collection is an examination of gifts and promised gifts to the museum. After that, I will put up the Larry Sultan show that comes from LACMA. We’ll have a show I’ve been working on called American Geography that looks at how we live in and use our land. In any case, when the next person in charge of the department is selected, I hope I can have a relationship that is important to the museum. I’d love to do things like work on the history of the department, which I think would be useful to everyone.

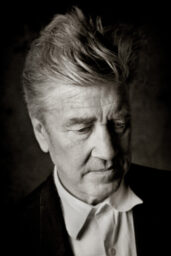

Larry Sultan, Isleton, from the series Homeland, 2009 © Estate of Larry Sultan. Courtesy SFMOMA

Helfand: What else is coming up in the first year or two of exhibitions?

Phillips: There’s a wonderful show of Anthony Hernandez, a photographer in southern California who has never had the attention his work certainly deserves. My colleague, Erin O’Toole, will be doing that.

Helfand: What was it like to have a three-year moment of working behind the scenes versus public presentations?

Phillips: It certainly was not easy. We were divorced from our collection. We’d have to go down to the collection center and work there to see it. But I would say it provided a time for us to really think about the collection in a more abstract way—what it really needed, what the goals were. We spent some serious time doing a kind of analysis of our department, a strategic plan. We were given this opportunity to rethink the department’s goals, refine our collecting objectives, and to rethink how the department works. That was really, really hard, and really, really important. It was a difficult but worthwhile period for us and I think we made very good use of that time.

Glen Helfand is a freelance writer and Associate Professor at California College of the Arts.