Christina Fernandez’s Multifaceted Visions of Life in California

With three exhibitions and a new book, the revered photographer’s study of labor, migration, and capitalism is as vital as ever.

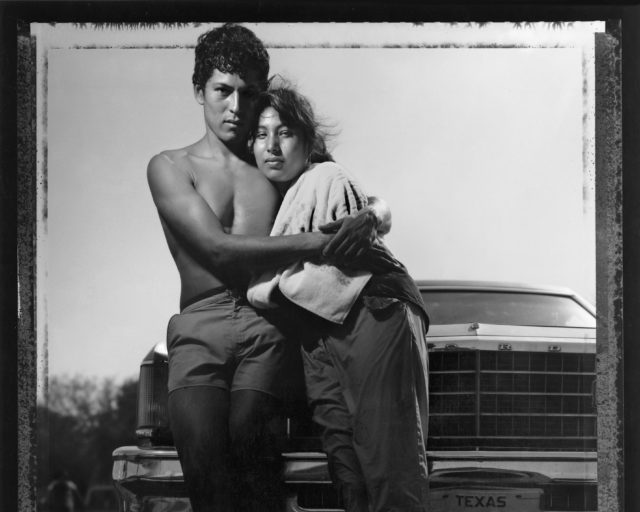

Christina Fernandez, Lavanderia #1, 2002, from the series Lavanderia

Christina Fernandez’s eye for images has changed. Recently, while going through contact sheets of her early work, the Los Angeles–based photographer wondered why she chose one image over another—like a writer editing an old draft with a fresh outlook on each sentence or slightly altering how each word leads into the next.

Fernandez’s career spans more than three decades, and this careful looking imbues much of her work. While her images aren’t defined by geography, she is a significant maker of California photography. The series View from Here (2016–18) includes images framed by doorways and windows in artist studios across locations like Desert Hot Springs, Joshua Tree, and Manzanar, the former site of a Japanese internment camp. Sereno (2006–10) captures scenes from El Sereno, the artist’s neighborhood in northeast Los Angeles, particularly those that hint at the parallel existences of nature and urban life. In Lavanderia (2002–3), Fernandez bottles the essence of Los Angeles laundromats, rendering blurry traces of the people who rotate through these spaces. Yet the themes of labor, migration, and capitalism in her work extend the images beyond any borders.

Now, Fernandez is gearing up for the release of her first major monograph, forthcoming in October, as well as three concurrent exhibitions. Her first significant survey exhibition, Christina Fernandez: Multiple Exposures, opens at the California Museum of Photography at UCR Arts on September 10 and runs through February 5, 2023. The exhibition also marks the first time the Lavanderia series will be shown in its entirety. Multiple Exposures will travel to places the artist says she’s never visited before—its future hosts are the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas; Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Arizona; Princeton University Art Museum, New Jersey; San José Museum of Art, California; and DePaul Art Museum, Chicago. (The exhibition was organized by UCR ARTS and is curated by Joanna Szupinska, senior curator at the California Museum of Photography, with curatorial advisor Chon A. Noriega, a distinguished professor of film, television, and digital media at the University of California, Los Angeles.)

Fernandez’s work doesn’t neatly fit into a single genre or photographic history. There are clear nods to street, landscape, and documentary photography, along with portraiture—plus elements of mediums like embroidery, collage, performance art, and installation. One particularly strong thread is Fernandez’s focus on socioeconomic inequities and her Chicana identity.

When Fernandez was growing up, her parents were organizers with United Farm Workers, and she would read newsletters that they often received from the group. Around the time of Cesar Chavez’s 1968 hunger strike, she says, the newsletters reported on the deaths of farmworkers due to pesticide exposure, violent attacks during boycotts, and dangerous machinery.

As an undergraduate student at UCLA, Fernandez typed the details of these deaths, and the names of the workers, onto index cards like those found in a library’s card catalogue. She then planted the cards in mounds of dirt so they stood upright. The resulting work, Untitled Farmworkers (1989), is significant in how it displays her effective weaving of activism, Chicanx identity, labor issues, and migration throughout her career. She revisited the piece in graduate school, photographing her brother’s hand as he placed each card into the dirt, then created a grid of thirty-five such images. But Fernandez says “it was basically shut down” in her critique class, and “the validity of the information was questioned.”

She has revisited the work at the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College, California, where her solo exhibition, Under the Sun, opened on August 24. The photographs of Untitled Farmworkers (1989) hang on a wall near a 2020 installation of the same name that references Fernandez’s undergraduate project; this time, the informational cards in the dirt show recent data on farmworkers’ deaths due to climate change. Both iterations of Untitled Farmworkers powerfully document these fatalities, yet the pieces “refuse the spectacle of death and suffering,” as art historian Cecilia Fajardo-Hill writes in the monograph. Fernandez’s work expands the ways a photograph can speak to the viewer. For the exhibition, the artist has also chosen to display works from the museum’s collection, thus generating new dialogue. They include press images of Cesar Chavez and of picket lines, as well as photographs by Danny Lyon.

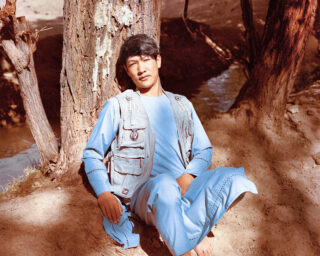

Fernandez has also explored her family history in works such as the 1995 to 1996 series Maria’s Great Expedition, which chronicles the story of her great-grandmother—a story that “just keeps on living,” she says, through exhibitions. To create the images, she spent hours thrifting for costumes and interviewing her family, fueled by “the energy and drive of youth.” She adds that she sees a certain fearlessness and dedication in earlier works such as this.

That daring spark led her to set up her four-by-five-inch camera on Cesar Chavez Avenue in Los Angeles to photograph laundromats at night for Lavanderia. Later, motherhood taught her to loosen her attachment to a specific theme or topic and instead go out in search of images. Around 2015, she started photographing during road trips with her son, adapting a more off-the-cuff process.

“I’m working on a few different things at once, and there is no singular approach to any of these things,” says Fernandez. “I’ve become comfortable working that way now.”

Fernandez asks her viewers to reconsider what may constitute a portrait as we know it. Though not traditional portraiture, her series American Trailer (2018) provides just enough context for us to imagine who might stand in the frame. The photos expand on the contradiction of a trailer as “this symbol of travel, freedom, comforts of home, [and a] sense of adventure,” she says, but also a sign of the housing crisis in the US. It brings to mind the figures of disillusioned Americans across the country: couples, families, and single folks dreaming of home ownership but discouraged by rising costs.

The image resulted from three different photography sessions. “The third time I went back, it had been burned down,” says Fernandez. “That’s the last part of the image you see—these sort of skeletal remains of the trailer. That piece just says what I wanted to, and I didn’t really see the need to continue to photograph other trailers.”

Fernandez calls it her most “spooky work” yet, and the specter of violence certainly lingers in the composition. A scorch mark could be read as the dark stain of hate crimes and division across the country, stoked by the political climate of the Trump administration as well as the unceasing power of white supremacy.

All photographs courtesy the artist and Gallery Luisotti, Los Angeles

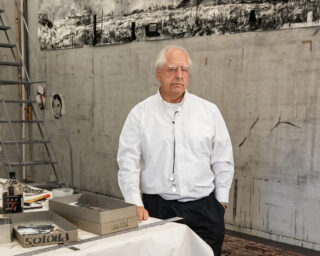

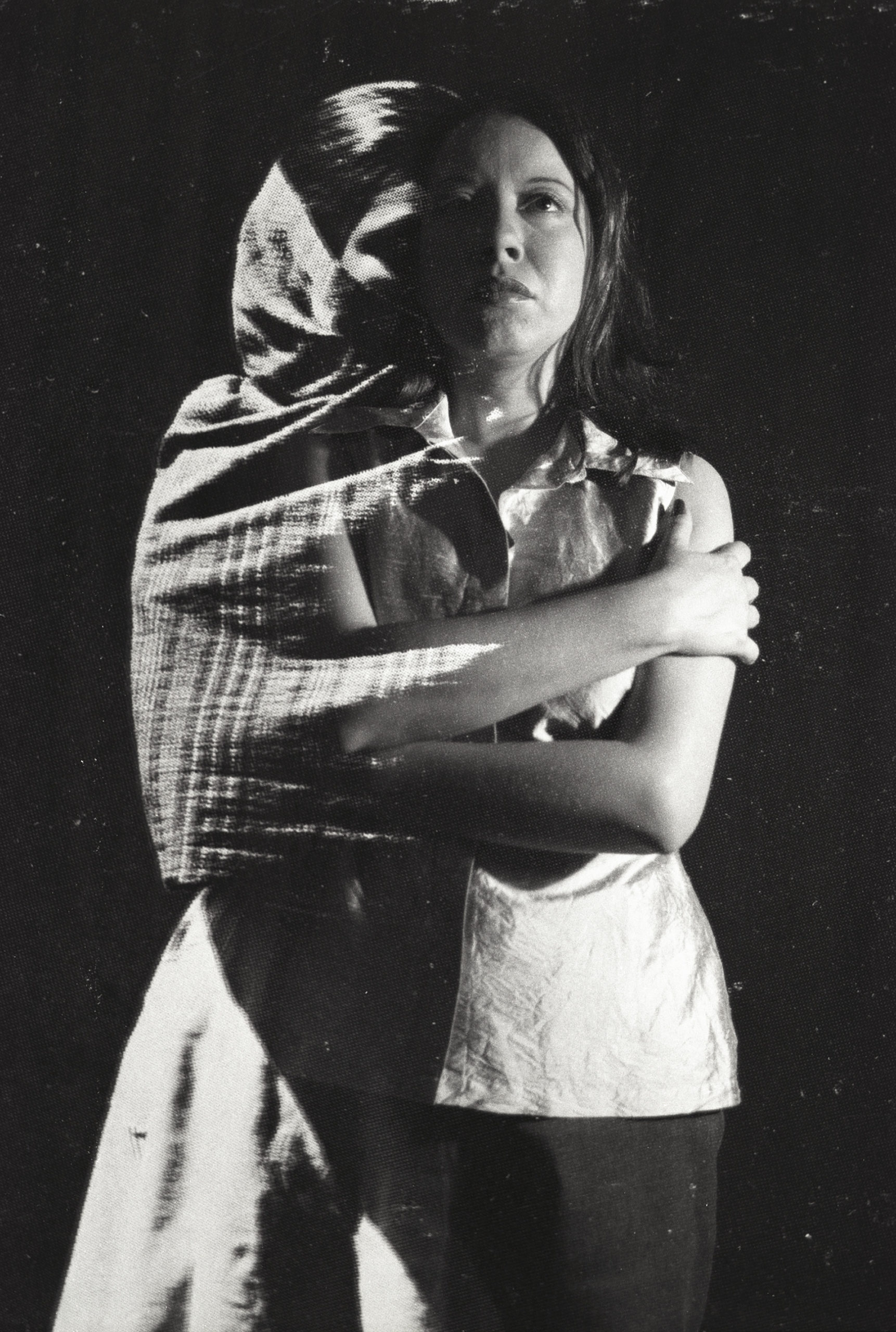

As Fernandez’s work has continued to resonate, she’s also focused on mentoring, teaching, and spotlighting the next generation of photographers. Her series reflect/project(ion) (2016–ongoing) depicts her former students, with an image of photo equipment layered over each portrait. Images in a forthcoming group exhibition, Tierra Entre Medio, opening September 11 at the Barbara and Art Culver Center of Arts in Riverside, California, is also all about a certain “commitment to the photographic language” that this next generation is embracing,” she says. The show, significantly, focuses on Fernandez and three other Chicana photographers in California: Arlene Mejorado, Lizette Olivas, and Aydinaneth Ortiz.

“A lot of people question the power of the photograph,” says Fernandez. “But even though I’ve tried a lot of different approaches to photographing, I’m still very much a traditional photographer. I still hang things on the walls. I still do think that there’s power in that 2D image. It’s just what you do with it.”

Christina Fernandez: Multiple Exposures is on view at the California Museum of Photography at UCR Arts, Riverside, from September 10, 2022 to February 5, 2023.