Myles Loftin Wants to Change the Conversation About Black Youth

Myles Loftin, 08, from the series HOODED, 2017

© the artist

Most people know Myles Loftin through his Instagram feed @goldenpolaroid. Loftin, who is only nineteen years old, has been using images to push back against stereotypical representations of black teens. His photographs—soft, bright, and a bit rebellious—are shared widely on social media platforms like Tumblr, where one post has garnered over 72,000 notes. Varied representations of black teens produced by black teens are important in any context, but the power of Loftin’s images lie in their vast reach.

A rising sophomore at Parsons School of Design, Loftin has shot for Urban Outfitters, Rookie, and The Fader. His recent series, HOODED (2017), challenges the negative, even deadly, perceptions of black boys wearing hooded sweatshirts. The series brings to mind John Edmonds’s Hoods (2016) images, which also examine the racially-coded nature of the hoodie; depicting only the backs of men’s heads, Edmonds suggests that even though black men are constantly watched, they are rarely seen. Loftin has a different approach: his frames explode with the joy and laughter of young men.

Matsuda: Your series HOODED really took off this year. How did it come about?

Loftin: I was scrolling through Twitter one day and I saw a tweet comparing the Google searches for “four black teens” and “four white teens.” The results for “four black teens” were mostly mug shots and courtroom shots. For “four white teens,” the results were stock photos of teens playing and laughing. That annoyed me. It’s upsetting that when someone is trying to find a picture of some black teens, the only thing that comes up are those pictures. It’s the first thing they see. I wrote this down in my journal and it sat there for a while. Last semester, I used this idea for a final project at Parsons. And then Milk published it!

Myles Loftin, 04, from the series HOODED, 2017

© the artist

Matsuda: The series also challenges a lot of ideas about black masculinity.

Loftin: It was natural for me because I don’t think I fit into the stereotypes about black men. A lot of my friends, and the people in the project, don’t fit either. They were just being themselves. Being yourself is a rebellion when the traditional representations of black male identities are hypermasculine and non-emotional. You’re not allowed to be intimate at all.

Matsuda: Sometimes when a project goes viral, it can get stripped of its context and turned into clickbait. Have you been happy with how HOODED has been presented and described?

Loftin: It has been good for the most part. I feel like some places went a little far with the clickbait. Saying “This Gorgeous Photo Series Crushes Stereotypes About Black Masculinity” isn’t really true. That makes it seem like I’m doing so much more than I actually have. It was only a project. It’s just a small part of this conversation.

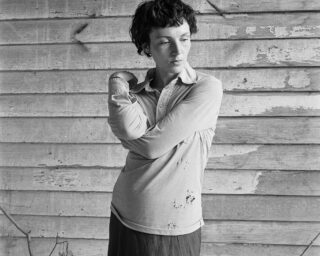

Myles Loftin, Untitled, from the series Potential Intermission, 2017

© the artist

Matsuda: This project seems more explicitly political than your other work. Has the current political climate affected your ideas about photography?

Loftin: I’m interested in conversations about representation, so I’m mostly photographing my friends and family. By photographing the people around me, I feel I am creating a more honest and accurate representation of people of color. Usually, I see watered down or exaggerated versions of who we are. I want to show what the people close to me are like. It’s more honest.

HOODED was my first political project. Before that I was just taking portraits of my friends, but I feel like I might do a project on the political situation. There’s so many racists who now feel they can say whatever they want with Donald Trump as president.

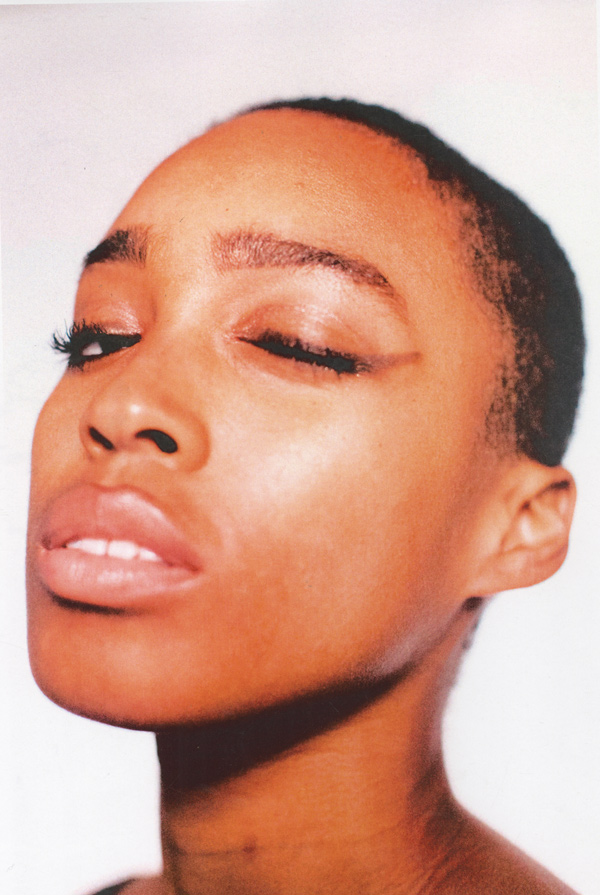

Myles Loftin, Synclare, from the series Synchilla, 2017

© the artist

Matsuda: But, even before HOODED, I think your work is political because you’re showing a different perspective on the many ways black teens can simply exist in the world.

Loftin: Yes, definitely.

Matsuda: How do you think images can fight back against these emboldened racists?

Loftin: The narratives of people of color are often created for them, not by them. This has led to the development of a system that automatically sees us as inferior. I think that visual art affects people in a different, maybe more personal way than words. An image can be a great way to fight back against racist narratives. That’s what I’d like my images to do.

Myles Loftin, Matthew and Darius, from the series Poolside Portraits, 2017

© the artist

Matsuda: There’s been so much discussion about “bubbles” and “echo-chambers” on social media. Do you think your work can connect with the people who disagree with you? Do you want it to?

Loftin: The Internet is one of the best tools to get your art seen by the people who really need to see it. When HOODED was published and shared on Facebook, there were many people commenting and agreeing with the very ideas that I was trying to argue against in my photos. I can only hope that my work gets through to those people. It may not happen immediately, but at some point I’d like it to influence a change in their thoughts.

Matsuda: Does your large social media following influence the kinds of images you make?

Loftin: Social media puts my work in front of more people and it gets me more work. Most of the work I’ve gotten has been through people who saw my work online. I’m not changing my work for my followers; I don’t make work just so 19,000 people will like it.

Matsuda: What photographers are you looking to for inspiration?

Loftin: Tyrone Lebon, Tyler Mitchell, Harley Weir, and Tim Walker.

Myles Loftin, Crimson, 2017

© the artist

Matsuda: That’s a pretty young crowd. Do you find yourself drawn mostly to young photographers?

Loftin: I really like looking at the work of young people because that’s mainly the work I’m interacting with on social media. A lot of the people I follow are around my age. Young artists come together because we share the same issues with being exploited by publications and companies who try to get you to work for free or for essentially no money. We’re not taken seriously! We’re not paid enough, if we get paid at all. That stuff brings us together.

Matsuda: Do you have any advice for emerging photographers?

Loftin: Value yourself and your work. Know what your talent is worth—and don’t settle for less. That’s so important to understand as a young photographer. When you know how much you’re worth, you’ll work really hard to get people to understand that.