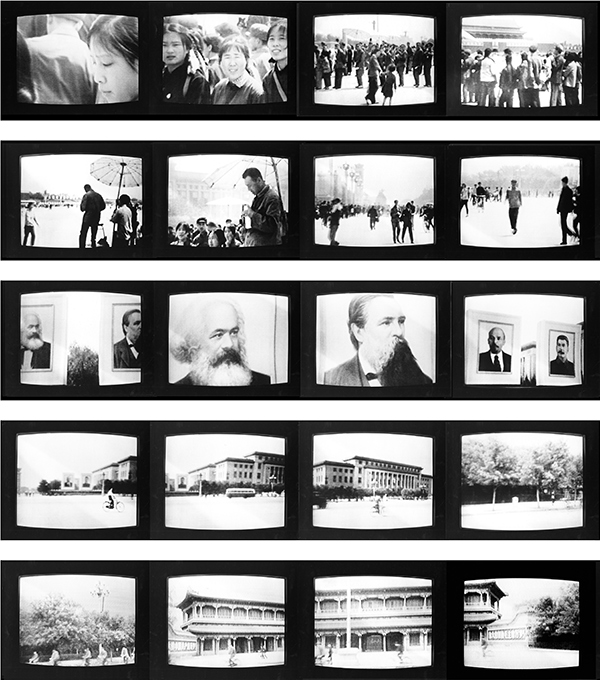

Peter d’Agostino, TRANS (detail), 1976

Courtesy the artist

In his 1970 essay “The Third Meaning: Research Notes on Some Eisenstein Stills,” French theorist Roland Barthes argued that the essence of film lay not in the motion or flux, but in the potential arrest of movement characterized by the film still. This move allowed Barthes to propose a structuralist theory of film in which the disruptive still is the key to filmic language, the punctum that pierces the narrative reading and reveals its obtuse meaning. In a stirring last line, Barthes proclaimed that such a “mutation of reading and its object”—text or film—was “a crucial problem of our time.” Taking up this challenge in the mid-1970s, Californian media artist Peter d’Agostino embarked on a series of photographic projects that deliberately interrogated the semiotics of film through a structural analysis of film stills, or what he prefers to call “stilled images.”

Courtesy the artist

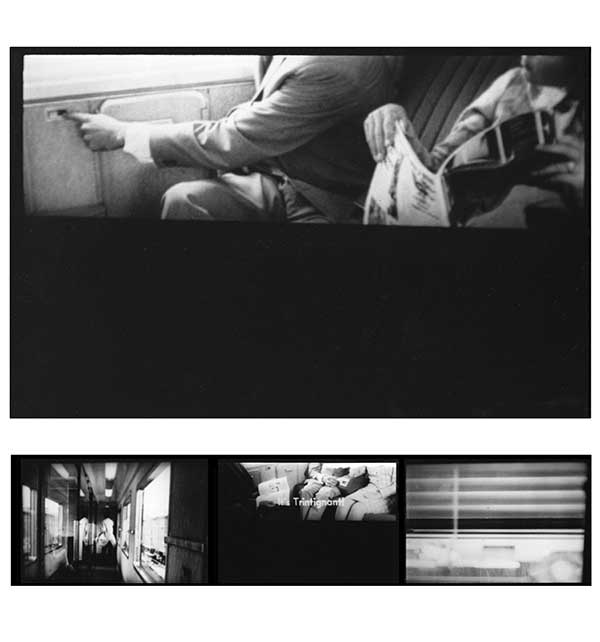

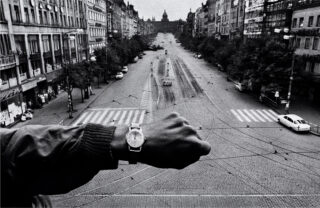

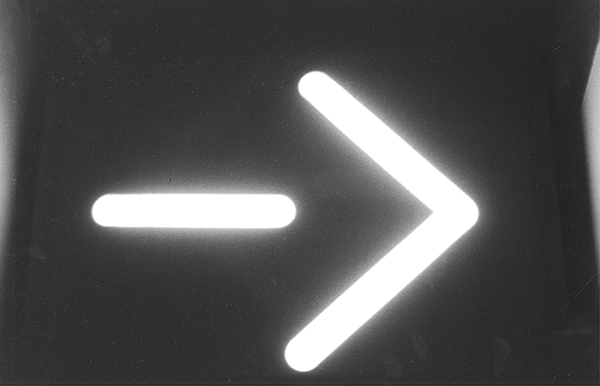

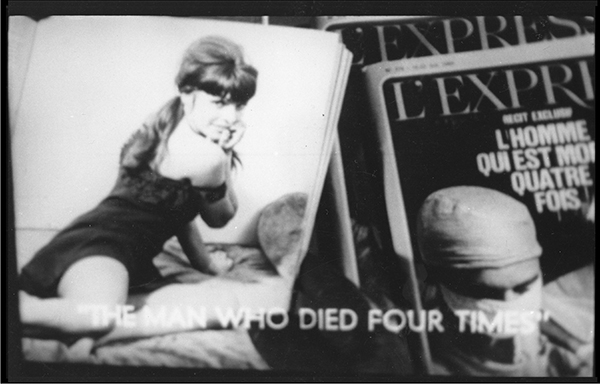

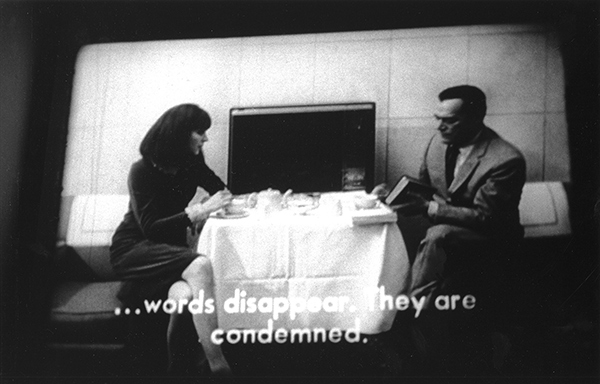

The heady mystique of the art-house underground of subtitled foreign films pervades d’Agostino’s slim artist book ALPHA, TRANS, CHUNG (1978), subtitled A Photographic Model: Semiotics, Film, and Interpretation. In this largely photographic book, d’Agostino documents several of his own disruptive interventions, time-based media installations that took as their raw material stills from three New Wave films, classics even then: Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville (1965), Alain Robbe-Grillet’s Trans-Europ-Express (1966), and Michelangelo Antonioni’s Chung Kuo, Cina (1972). For the first project in d’Agostino’s book, ALPHA (1976), the artist reduced Godard’s dystopian sci-fi film to thirty-six stilled frames on a single contact sheet. From this, d’Agostino distilled eight photographs to summarize the film’s attention to, on the one hand, the formal events of light and time, and on the other hand, the dissolution of language. For the second chapter, TRANS (1977), d’Agostino analyzed Robbe-Grillet’s dazzling film-within-a-film by slowing the action, lingering on certain details, and incorporating the responses of the audience, filmed in real time. The third section, CHUNG: “Still” Another Meaning (1977), employs stills from the opening of Antonioni’s lengthy documentary, commissioned by the Chinese government, to consider why China censored the film and harshly rejected the filmmaker’s depiction of “their” reality.

Courtesy the artist

But ALPHA, TRANS, CHUNG also contains a dazzling appendix of pertinent metacritical texts by Robbe-Grillet, Umberto Eco, Lew Thomas, Kristine Stiles, Hal Fischer, and others, showing that d’Agostino is above all a media experimenter and theorist. In addition to his many innovative and interactive installations, d’Agostino has written extensively and compiled several significant anthologies, including Still Photography: The Problematic Model (1981), with Lew Thomas; The Un/Necessary Image (1982), with Antonio Muntadas; and Transmission: Theory and Practice for a New Television Aesthetics (1985). Some writers have related d’Agostino to a loosely affiliated Bay Area group around the publication Photography and Language (1976), for which his contact sheet from ALPHA served as the cover image, or described d’Agostino as a “conceptual photographer,” a phrase he rejects. But as he said to me recently, “I am an artist working with/utilizing photography, not a photo/language or conceptual photographer.”

Courtesy the artist

By no coincidence, ALPHA, TRANS, CHUNG—which doubled as a catalogue of d’Agostino’s 1978 exhibition at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio, where he then taught—functions in a similar way to his other anthologies: it combines specific examples of media practice with clear theoretical texts to advance a radical critical thesis. As the press release for the 1978 showing of the project at Artists Space in New York stated, “[ALPHA, TRANS, CHUNG] is a model of the interrelationships of various means of symbolic communication, visual as well as verbal. In terms of the media, it utilizes the similarities shared by film, photography, video and the written word.” In ALPHA, TRANS, CHUNG, d’Agostino wields the film still like a scalpel, to dissect the social, cultural, technological, and even psychological ramifications of media images. The goal for d’Agostino, as for Barthes, was the delineation of a semiology of film and photography, as a social language, a system of signification in everyday life.