Tom Sandberg: Photographs 1989–2006

In memory of leading Norwegian photographer Tom Sandberg, who died February 5, 2014, Aperture republishes “Tom Sandberg: Photographs 1989–2006”. This exhibition review appeared in the Fall 2007 issue of Aperture magazine.

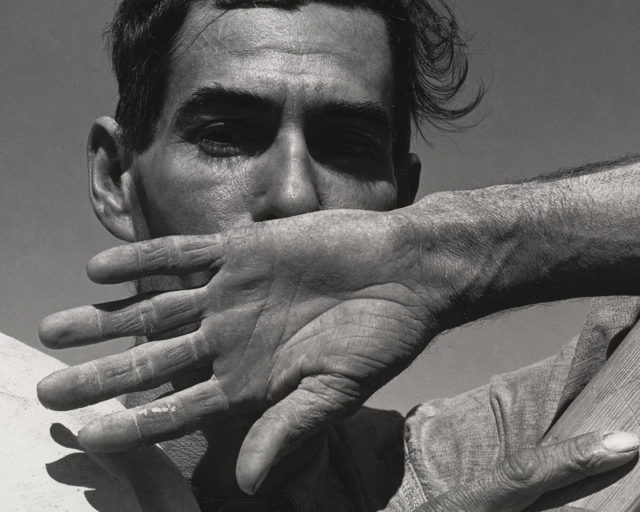

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2005. Courtesy the artist/Galleri Riis, Oslo.

Tom Sandberg is an old punk rocker living and working in Oslo, on the former estate of his nation’s beloved son Edvard Munch—as such, it has taken some time for his photographs to make it to the United States. And he still doesn’t seem to be in any big hurry. Patience, it would seem, is something more than merely a virtue; it is an aesthetic. Sandberg didn’t find some great vindication in having a mid-career retrospective at P.S.1/MoMA, or construe this first exposure in New York as a “big break.” Moreover, his work itself is hardly in a rush to be seen or understood.

In our ever-increasing image glut, often when it comes to an exhibition of many pictures we can’t help scanning through them, reading them together in clumps, rather than making the investment of entering each individual world. More to the point, however, there is little about Sandberg’s art that commands attention. His pictures insinuate themselves through their modesty, and demand a level of scrutiny by their very gift of being non-apparent. It’s not always even that obvious what we are looking at—this, perhaps, is what makes these images stick: they are like unresolved memories, at once disclosed and foreclosed.

Sandberg is not afraid of abstraction: it has to be here, as a component of how the world fits together. But the mysterious quality of his apparently simple pictures is far too literate to elicit a mere “What’s that?” The enigma is something of a metaphor—Sandberg has a very careful and dedicated way of looking that is by normative experience quite uncanny. In the inventory of his work, we might be hard pressed to find anything we haven’t had a look at before; and yet everywhere he puts his lens he renders the unmistakable sense that we are now seeing in a way that we usually don’t. Does he have a great eye? Sure, but the ineffable quality of his work is neither evidentiary nor visionary; it is, instead, essentially the effect of an obsessive fascination with those elements of photography in which subtlety can play out with infinite complexity. Sandberg’s art is not a product of experience; it is a process of experiencing. His choice of subject is inherently eclectic—sometimes immensely vast, sometimes intimately small; the real drama is a visual dialogue on the nature of perception. The language—honed by craft—is very much about photography.

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2004. Courtesy the artist/Galleri Riis, Oslo.

Sandberg makes large-scale prints, most often silver bromide on extremely thin sheets of aluminum (and at times, to quite different effect, on cotton canvas); it is hard not to get sucked into their “window” effect, to be swept up in their unapologetic pictorialism. Even in those most man-made of topographies that Sandberg captures, the abiding commonality throughout his oeuvre is unmistakably nature. Which sort of makes you wonder. How could a tunnel, an airplane, or some nonspecific segment of industrial piping seem as natural as the mountain/cloud/seascapes that more frequently sprawl before us in Sandberg’s sweeping poetics? Why, for that matter, would any of these subjects resonate as deeply personal? Sandberg’s gift involves a remarkable capacity to imbue the quotidian with psychological gravitas. He is, in that great photographic tradition, a master of light: it is everything that plays here, that exposes and subsumes, that articulates and ultimately falls back into the shadows of what remains unsaid in Sandberg’s art.

There is a majestic silence—palpable to the point of monumental—in this work. Elegant and ancient as the subject of his evocative portrait of John Cage (1985/94), this silence never takes form, but affects what is around it, shaping the atmosphere. The most obvious fact of Sandberg’s photography—that it has developed over the past thirty-five years in an adamantly black-and-white nondigital medium—is both its forte and its fallacy. This is anything but black or white; it is a symphony of hues and tonalities in which any words suggesting “gray” or “off-white” are as useless as describing a sunset to a rock. This is the kind of impression you might get if you’d been watching crummy worn versions of old movies on TV your whole life, and suddenly saw a newly re-mastered print in the cinema. And boy, is this cinematic— and all the more disturbing for being a silent film—starkness as symbolism shrouding a hermetic allegory, stills like gestures, some narrative always lurking outside the frame.

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2002. Courtesy the artist/Galleri Riis, Oslo.

Perplexed, haunted, truly at a loss as to what Sandberg was after, I asked him. Of course, he’s not one for words, mistrusting them as anyone who treasures magic would loath explanation. He does admit that our (lazy) tendencies to look for something particularly Norwegian about his art may not be unfounded. It’s been a long time, but he did grow up on Ingmar Bergman films, and as for that light: “It’s so dark and dull there, you do reach for the light. It’s in your body to do so.” That light—in the distance, just out of reach—is everywhere in Sandberg’s work.

—

Tom Sandberg: Photographs 1989–2006 was presented at P.S.1/ MoMA, Queens, New York, February 11–April 23, 2007.