If Photographs Could Talk

How has an experimental platform for photographers created a new form of image making?

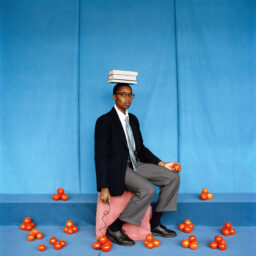

Eric Ruby, February 17 (detail), 2017

What does it mean to talk in photographs? In 2014, the photographers Ben Alper and Nat Ward started an image-based conversation, and they haven’t stopped talking since. A lot has come up in that time, and, through alternating contributions, their exchange has covered topics such as violence, fantasy, patriotism, nature, and death. The dialogue formed as an open-ended experiment, but they have stuck to the same format throughout: a photograph from one, a photograph from the other, repeat.

“It’s like an ‘exquisite corpse’ exercise, or the sequencing of a book of photographs,” Ward said recently. “The visual content has to talk from one image to the next, making and augmenting a legible kind of meaning along the way.” It didn’t take long for a compelling rhythm to emerge in Alper and Ward’s give-and-take, which stirred up curiosity about how other photographers might use pictures to talk. They invited friends to start conversations of their own and the project expanded outward from there. Today, A New Nothing, the website Alper and Ward created to house these exchanges, has over one hundred active contributors.

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

The parameters of the project are simple, but A New Nothing is full of layered and provocative interactions. A column of paired names works as the table of contents on the website, each pair cueing a gallery containing the back-and-forth between two photographers. Images are accompanied only by bare-bones captions that list the date the post went up and the contributing photographer’s initials. There are no statements or bios, and each exchange moves at its own pace (in some, weeks pass between posts).

The pattern of alternating posts established in Alper and Ward’s founding interaction unites the conversations. Otherwise, each duo develops the tone and guiding principles organically, as their discussion unfolds. “Those impulses and decisions remain largely hidden or unverbalized,” Alper said. If photographers decide they no longer want to continue participating the contributed work remains online in archived conversations (some of which Alper and Ward plan to release in book form in the future), but such end points are never established up front. Context and intention here are meant to evolve publicly.

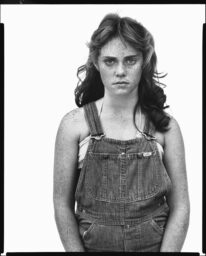

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Sometimes, it’s easy to make out the connective tissue between individual photographs in the conversations. “Talking” often means making playful turns to echo and invert colors and shapes between pictures. In a photograph by Eric Ruby, someone has slung a friend over their shoulder to carry them down the beach. As a response, Damien Maloney shows us a snail atop a green melon; the tie-dyed striping on a T-shirt in Ruby’s picture has jumped to the melon’s skin in Maloney’s scene. When images are enlisted as responses and rebuttals, compositional elements might be mimicked repeatedly, until the original form dissolves, like an object fading into its own reflection between two mirrors, or a message getting garbled in that children’s game “telephone.” Certain subjects will appear and then travel between frames. In a conversation between Joy Drury Cox and Peter Happel Christian, we see flowers, wrapped and ready to be bought, then backlit on a windowsill, and, before the motif is abandoned, placed in vases affixed to headstones.

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

As subject matter and form are batted back and forth between two photographers, as if over a tennis net, stylistic choices take on a gestural quality. Because photographers get to choose whether to recognize, reject, or repeat elements in their partner’s picture, their aesthetic inclinations look a bit like character traits. Tracking the patterns, or the flowers, or the range of greens that bridge from a pack of pickles sprawled on a painted surface to a tree-shaped car air-freshener floating in some sludge, we see lots of clever ways to shift expectations.

We also see how talking in pictures, like any sort of conversation, reveals the interlocutors’ dispositions. Photographers whose work pulls from too expansive a palette, either aesthetically or in terms of subject matter, might seem scattered or ineloquent. On the other hand, sticking too closely to a subject, like when Arthur Ou posted only photographs of tree trunks in his conversation with Grant Yarolin, might make you look stubborn or obsessed.

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Many photographers appear liberated by the purpose (or purposelessness) of the format, which encourages a particular sort of uninhibited expression. Humor often results. One of Irina Rozovsky’s photographs was shot from the driver’s seat of a car on a snowy day. On the camera’s side of the windshield, a hand is pinching a hard-boiled egg between thumb and forefinger. A bite is missing from the egg and, outside in the slush, a bundled man is in the middle of the crosswalk. In response, Mark Steinmetz shows us a line of chickens crossing the road. Why? Because of the driver’s snack.

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

“It’s this sort of prism of different places, different things, linked by something unspoken,” Rozovsky said of her conversation with Steinmetz. Their exchange began with two photographs of the same scene, taken in Athens, Georgia, in 2014, while Rozovsky was visiting Steinmetz. They were friends then and have since moved in together and had a child, continuing the conversation throughout. The exchange “loses a little bit of energy when you’re together, seeing the same things,” she said. “But it’s really fascinating when you’re in different parts of the world. The resonance of the echo across the divide is really exciting.” Methods for these visual interactions—the flipping, the mirroring, the inversion of ideas—have a give-and-take quality good for shaping everything from visual puns to the bridging Rozovsky describes.

© the artist and courtesy A New Nothing

Divorcing these images from traditional sequence editing, accompanying text, and layout decisions creates a spare, fluid atmosphere where subjectivity swells. At the same time, there is this unspoken but apparent etiquette in each conversation on A New Nothing, and the tension between those aspects is part of what makes the project such an engaging trove. Messaging here rides entirely on the form and content within the frame, and the capacity of individual photographs expands in unlikely ways. We watch as it happens, guessing at what will be said next. All of this makes scrolling through the conversations feel like listening in on friends talking in the codes of inside jokes reserved for private spaces, or, as Ward said, “like reading the body language between two people at the other end of a bar.” The playfulness, the humor, and the challenges the conversations present have a way of deflating—rather refreshingly—the objective authority photographs so often assume.