In “African Spirits,” A New Visual Vernacular

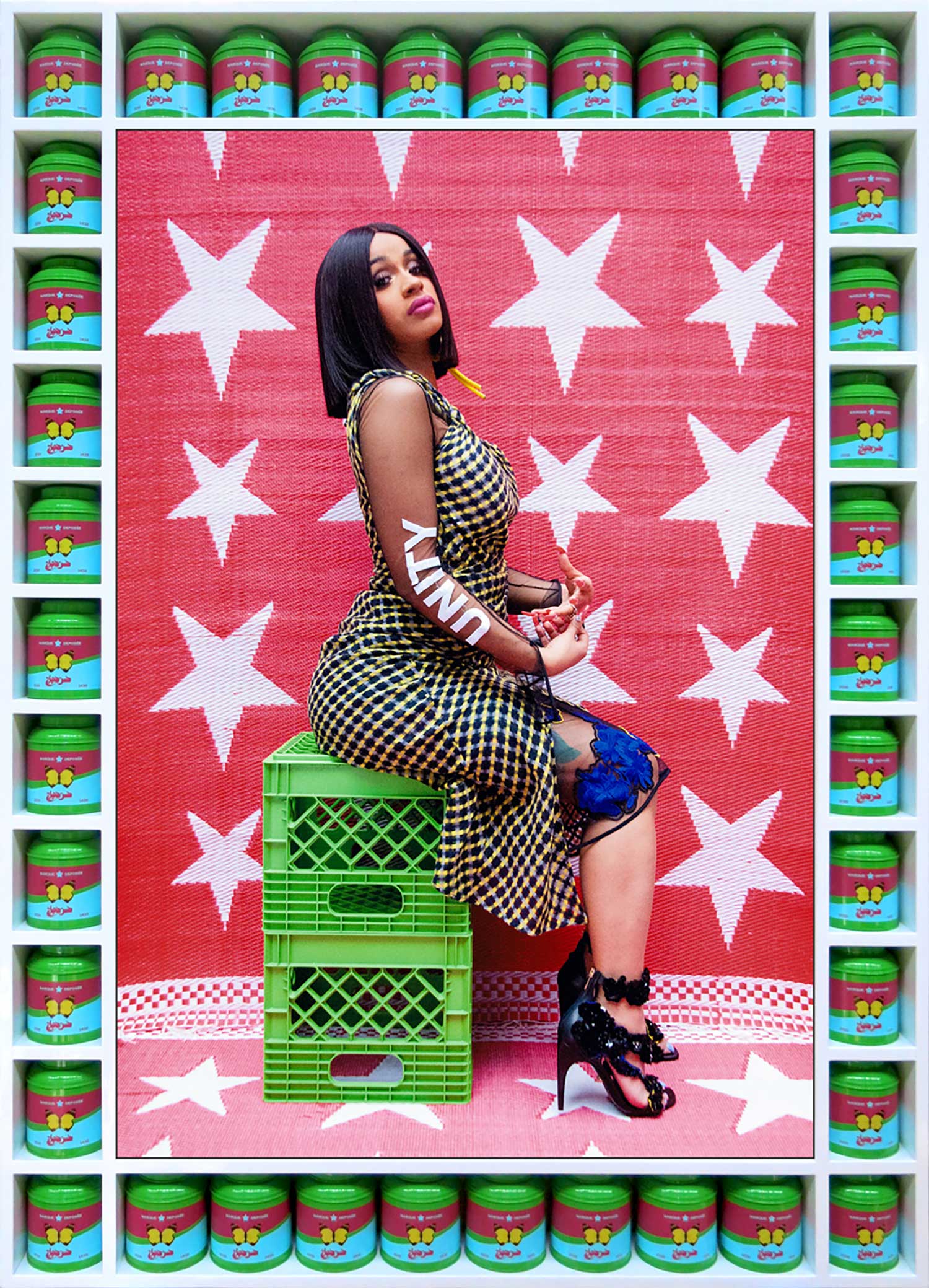

Hassan Hajjaj, Cardi B Unity, 2017

© the artist and courtesy Third Line Gallery, Dubai, and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

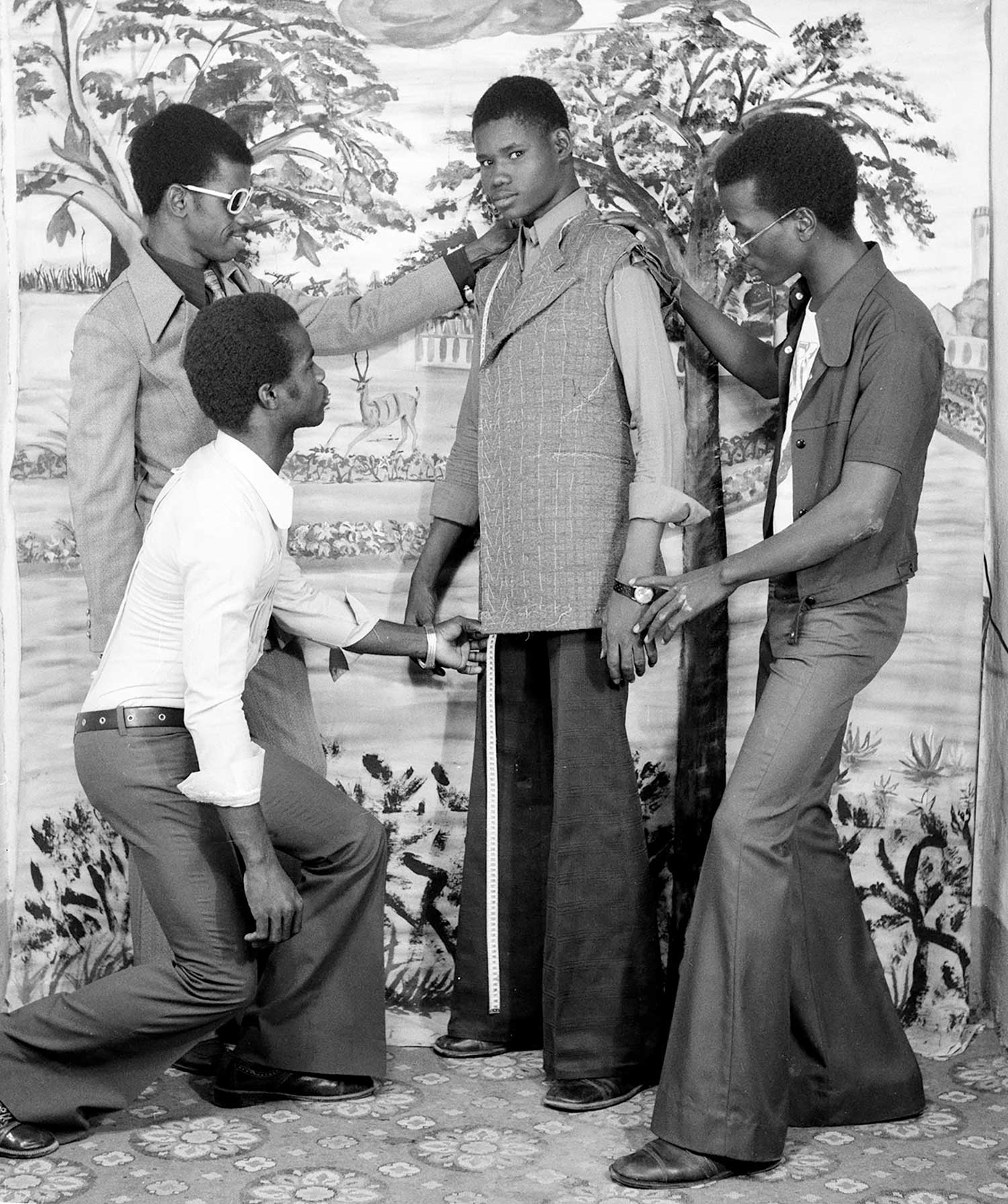

African Spirits, currently on view at Yossi Milo Gallery in New York, presents an astutely and carefully crafted panoply of African photography, conveying the mastery and evolution of a bold and—I would add—fly visual vernacular. Juxtaposing approximately sixty-five works from the 1950s to the early 1980s with contemporary pieces by artists across the African diaspora, the exhibition initially overwhelms. Modern prints of black-and-white portraits seemingly clash with the yellowed, aged edges of vintage prints from both celebrated and little-known studios. The image sizes vary, pulling the viewers toward and away from the faces, clothing, and postures of their subjects. But who are these people?

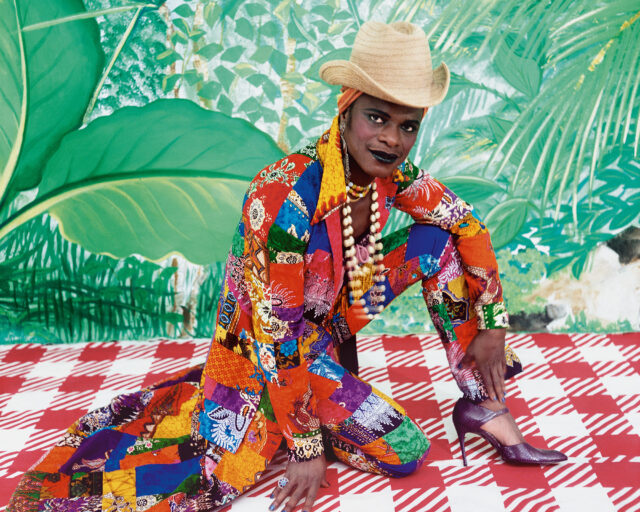

Leonce Raphael Agbodjelou, Untitled, from the series Citizens of Porto-Novo, 2018

© the artist and courtesy Jack Bell Gallery, London

Decidedly adorned and decisively posed. Or candidly photographed and sincerely expressive. They are citizens of a new social world, one defined by the transformations of the independence movements that swept Africa in the 1960s. There is motion and agency in these bodies, whether clothed or undressed, choosing if and how they are looked at. The works that constitute African Spirits embrace self-possessed subjects and a reverence for the quotidian, molding the inherently subversive foundation of postcolonial African portraiture.

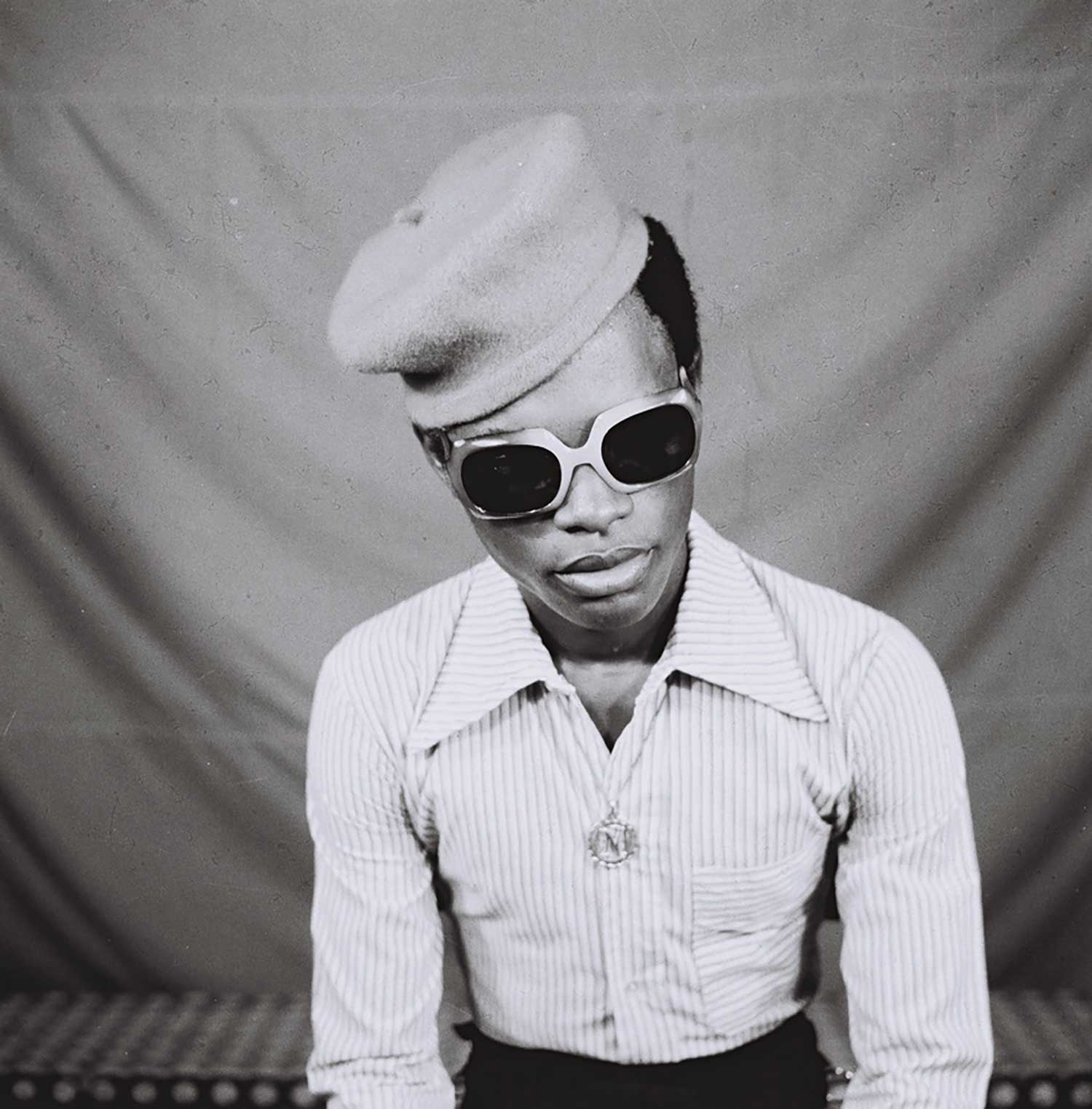

Samuel Fosso, Autoportrait, 1975–78

© the artist and courtesy Jean Marc Patras Galerie, Paris

The title African Spirits is a reference to Samuel Fosso’s series of the same name from 2008, which was recently acquired by the Museum of Modern Art and presented at its 2017 collection exhibition, Unfinished Conversations. The series is not on view here, but the exhibition does include some of Fosso’s earlier work, alongside that of Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé, Sanlé Sory, and J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, as well as contemporary artists such as Zanele Muholi, Morgan Mahape, Hassan Hajjaj, Pieter Hugo, Leonce Raphael Agbodjelou, and Delphine Diallo.

Delphine Diallo, Afropunk – Pink Fur, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Fisheye Gallery, Paris

An openly queer artist, Diallo gives the show a pop of color with Afropunk – Pink Fur (2016). This portrait of a femme, embodying queer femininity and queer masculinity, complements Mohamed Bourouissa’s nearby image from the series Périphéries, of two men, a boxer and a coach. Pink Fur also converses with Agbodjelou’s Untitled (2012), from the series Musclemen, which depicts three bare-chested men, arms crossed, with different patterns on the fabric of their pants, the backdrop, and the floor. Fosso’s self-portrait works from the series 70’s Lifestyle portray the artist in various costumes of flyness that queer manhood, allowing him to literally and figuratively try on new identity “types,” ultimately fashioning a self as photographer and as subject.

Pieter Hugo, Mimi Afrika, Wheatland Farm, Graaf-Reinet, 2013

© the artist and courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Sidibé’s contact sheets ARROSAGE DES TROIS, ADMIS NIARELA, 28-9-68 (1968) and Nuit du 18-19-11-69 (1969) embody the exhibition’s impulse toward quotidian delights. In her book Listening to Images, Black feminist scholar Tina M. Campt defines the quotidian as “a practice honed by the dispossessed in the struggle to create possibility within the constraints of everyday life.” These images are fragmented archives of the subjects at their best, showing up and showing out on the dance floor, embracing the moment and one another. While the quotidian is not spectacular, it is special. African subjects fashioned agency in front of the camera and in everyday life. Hugo’s large-scale photograph Mimi Afrika, Wheatland Farm, Graaff-Reinet (2013), from the series Kin, amplifies the intimacy of Sidibé’s smaller vintages. Hugo captures an older African woman adorned in a pink collared shirt and ornate gold-print headscarf. Most would see her skin’s texture and the beauty in her naked wrinkles as the photograph’s punctum. However, I see the few locks of her hair that she has shed, subtle kinks sitting here and there atop her shirt. The photograph is immaculate in its presentation, yet especially beautiful in its mundanity.

Studio Degbava, Untitled, ca. mid-twentieth century

© Studio Degbava

Similarly poignant, one of the photographs from the lesser-known Studio Degbava depicts a woman throwing her head back in ecstasy. We cannot see her face. To get to know her joy, one must step in close. Arms akimbo, with her hands cinching her dress, she draws attention to her shoes. Left foot turned out, proud and feeling herself. What does it feel like to escape at just the moment of capture? Perhaps like this. Muholi and Mahape’s beaded portrait Somnyama Ngonyama (2019) continues this conversation of expansive feeling. Similar to Black American artist Mickalene Thomas’s Din, une très belle négresse #1 (2012), Muholi and Mahape employ a plethora of cultural artifacts and practices, suggesting that paint and print are no longer enough to communicate the fabulosity and complexity of the Black subject.

Hamidou Maiga, Untitled, 1973

© the artist and courtesy Jack Bell Gallery, London

The camera’s introduction to the African continent has fashioned a visual vernacular that persists even as it has morphed from the commercial photo studio of the ’60s and ’70s into the cross-cultural collaborations of today. African Spirits captures the specific aesthetics and ambiguities of African selfhood. We can look to the images of Fosso, Sidibé, their contemporaries, and their successors to access the worlds their subjects crafted in the aftermath of violence, migration, or political independence. Most importantly, we can bear witness to who these subjects decided to become.

African Spirits is on view at Yossi Milo Gallery, New York, through August 23, 2019.