The Radical Power of the Black Feminine Gaze

Carrie Mae Weems’s unwavering vision sparks dialogue about violence, mourning, and strength.

Carrie Mae Weems, Lincoln, Lonnie, and Me – A Story in 5 Parts, 2012

© the artist and courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Black feminists, Black women artists, and Black feminist artists have a laborious tradition in witness work. They imagine futures unseen. They engineer poetic tools of resistance and provocative encounters. Through their paintings, sculptures, images, performances, fabric works, moving images, and writings, Black women convey the essential connections between the body and spirit with compassion for states of mourning and healing.

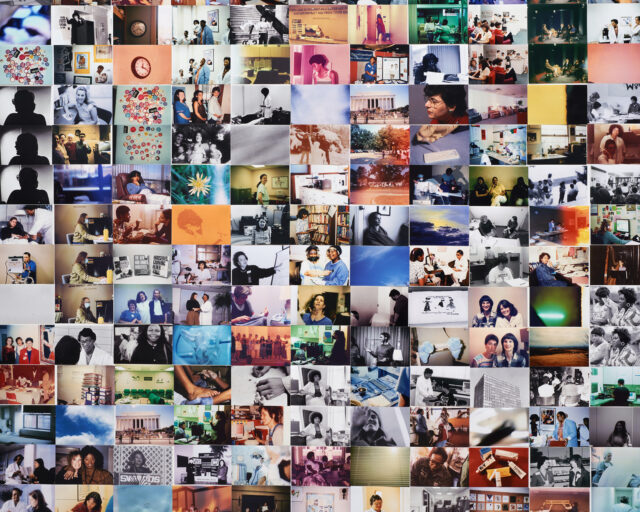

Carrie Mae Weems’s interdisciplinary practice of portraiture, documentation, and storytelling is a part of this legacy of women who work in remembrance and refusal. Her current two-site exhibition at Jack Shainman Gallery is a sharp, meditative assembly of ideas and questions that extend her career-long disruption of conditioned perception and viewership. In her new series, Usual Suspects (2016) and Scenes & Take (2016), Weems tackles power structures as represented by American media, and state-sanctioned violence.

Carrie Mae Weems, Scenes & Take (The Bad and the Beautiful) (detail), 2016

© the artist and courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

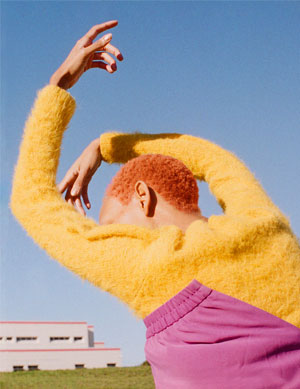

The evolution of Black feminist cultural production and political thought has sought to articulate the intimate relationships between the body and power, the body and violence, the body and capitalism. Weems has frequently drawn upon these dialectic relationships. One of her recurring devices, a Black woman avatar—who is present in photographic work from the Kitchen Table Series (1990) to The Museum Series (2006–ongoing)—relies on the strength of a Black feminine gaze. The avatar confronts viewers with scenes and sites both startling and familiar. This avatar, an enigmatic character whose sightings we have all come to relish, is a witness and a guide.

In a 2009 interview with the photographer Dawoud Bey, Weems said, of the avatar, “Carrying a tremendous burden, she is a black woman leading me through the trauma of history. I think it’s very important that as a black woman she’s engaged with the world around her; she’s engaged with history, she’s engaged with looking, with being. She’s a guide into circumstances seldom seen.” Weems continues, “She’s the unintended consequence of the Western imagination. It’s essential that I do this work and it’s essential that I do it with my body.” Her avatar doesn’t wander or drift about; she is determined. She is a lens, a way of seeing. We look and journey with her.

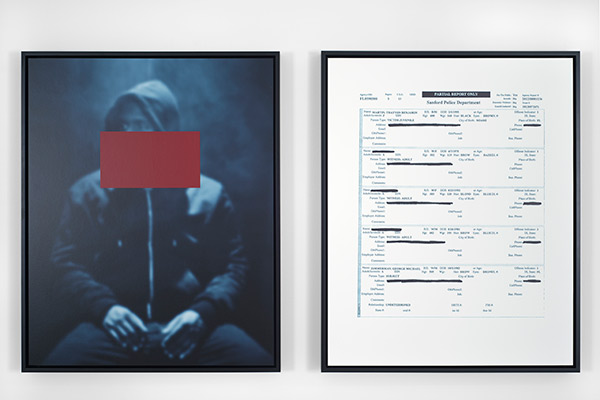

Carrie Mae Weems, All the Boys (Blocked 2), 2016

© the artist and coutesy Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Black women have always been at the forefront of national dialogues around state-sanctioned murders and the rituals and processes of mourning. Weems’s approach in addressing the murders of Black children, women and men at the hands of America’s policing citizens is to forge an unmistakable reckoning. From Usual Suspects (2016), a grid of nine panels featuring descriptions of deadly encounters, to the enlarged fragments of police reports in the series All the Boys (2016), Weems conspicuously displays the fruit, the evidential repetition, of racial injustice.

“The history of Black women is a long study in mourning,” Jessica Millward stated recently. “The mourning takes on an added layer, however, when those sworn to serve and protect proceed to hunt and kill furthering African Americans’ long distrust of the government.” In the face of racial violence, the Black feminine gaze is a radical aesthetic, a technology that generates its own framework for the production of art, culture, and resistance. At this moment in America, a Black feminist vision is consequential for the future, and Carrie Mae Weems’s feminist vision has never been more timely.

Carrie Mae Weems is on view at Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, through December 10, 2016.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.