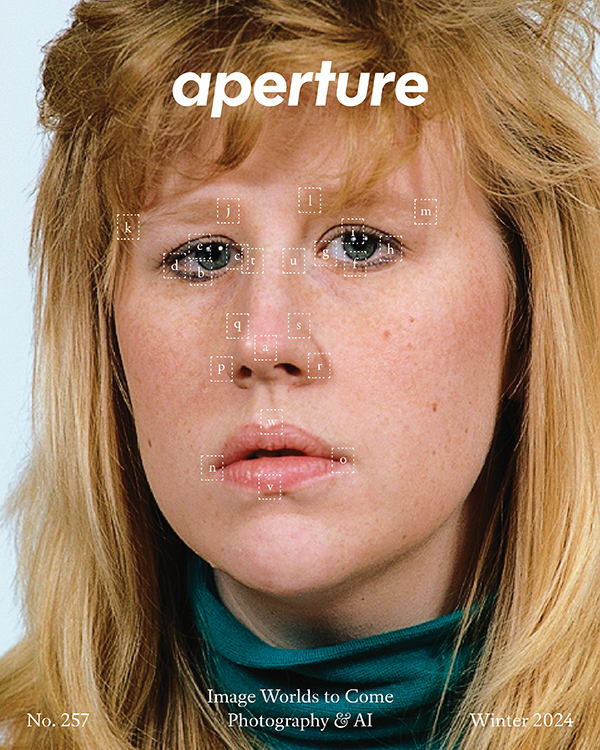

A Photographer's Chronicle of Indigenous Life in Brazil

This piece was originally published in Aperture, issue 215, Summer 2014.

On one of the hottest days of the Brazilian summer last February, I sat with Claudia Andujar in her apartment to talk about her remarkable life and career in photography. Claudia, now eighty-three, has lived in São Paulo since the mid-1950s, but the story of how she came to live in Brazil parallels some of the tragedies of the twentieth century. Born in Switzerland, Claudia spent her early years in Hungary, before fleeing during World War II. She lived in New York, where she finished high school, attended Hunter College, and embarked on a career as a painter. After a brief marriage, Claudia rejoined her mother who was living in São Paulo, in 1955, and left painting for photography. During the 1960s, Claudia returned regularly to New York, maintaining ties to the city’s artistic community, including figures like Edward Steichen and documentarian W. Eugene Smith, who would profoundly influence her humanist vision. Her photographs were published in Life magazine and in Aperture, in 1971, then edited by Minor White. In 1960, her work was included in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

In Brazil, Claudia worked as a photo-journalist for magazines such as Realidade, until the early seventies, when she quit everything to focus on a personal project about the struggles of an indigenous group in the Amazon region called the Yanomami. This would become her life’s work. She photographed the Yanomami extensively, in hopes of preserving and understanding their culture, and fought politically for the respect of their traditions and land. today, Claudia has not slowed down. In September, Inhotim, a contemporary art museum in the state of Minas Gerais, north of São Paulo, will inaugurate a permanent pavilion dedicated to her work on the Yanomami. I am currently organizing an exhibition, opening at the Instituto Moreira Salles in Rio de Janeiro in 2015, focused on Claudia’s career, which includes her years in photojournalism and her experiments with color and infrared film.

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Thyago Nogueira: How did someone who was born in Switzerland and grew up in Hungary end up living in São Paulo?

Claudia Andujar: It’s a long story. My mother was Swiss and my father was Hungarian. They lived in Transylvania, a place that was sometimes Romania and sometimes Hungary. For some reason—I should have asked why—she wanted me to be born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, and so she went there for my birth.

We then came back to our city, which is called Oradea in Romanian (in Hungarian it’s called Nagyvárad). We lived there until World War II. In 1944, all the Jews were deported. My father was Jewish. He and his whole family were deported; they died in a concentration camp. I was living with my mother, who was divorced from my father. After he was deported, the Russians began closing in, so my mother decided to go to Switzerland. The rail trip took weeks because of all the broken bridges on the way. We also had to stop in Vienna, because my mother became ill. In the city, which was under German rule, my mother stayed at a hospital and I was interrogated daily. They wanted to know why we had fled. I had to hide the fact that my father was Jewish or they would have taken me. They never discovered my story. I stayed in Switzerland for two years, until one of my father’s brothers found out that I was there and asked me if I wanted to come to the United States. I went as a refugee to New York in 1947 to live with my aunt and uncle.

Nogueira: How was your time in New York? Why did you leave for Brazil?

Andujar: I didn’t really get along with my aunt and uncle. They accused my mother of leaving my father. It’s a complicated story …. I decided to rent a room and go to work. I worked at the United Nations and I painted. At night I studied at the university. After a while I felt abandoned and married a Spanish refugee; that’s why I have the name Andujar. But he became a soldier in the Army and had to go to Korea. I was really unhappy. At that time my mother was living in Brazil, where she had gone to marry a Romanian who ran away from the Russian occupation. After two years, my husband returned from Korea and we separated. I then decided to visit my mother. That’s how I came to Brazil, in 1955.

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Nogueira: When did you take up photography?

Andujar: I abandoned my painting career when I arrived in Brazil. But I needed a language to communicate—for me, this was photographing people I met. I wanted to get to know Brazil because I felt at home there. So I picked up a camera, and when I could, I photographed. I’m self-taught. I would go to the north coast of São Paulo a lot, and I began to travel to the islands of the fishermen and became friends with the families. What interested me were the origins of Brazil, the native population. I wasn’t interested in the middle or upper classes.

Nogueira: Did you ever feel unsafe as a European woman traveling alone?

Andujar: No, traveling was easy. In the crowd I was mixing with, this wasn’t a problem at all. I was adopted by the families of these people. I think that the connection through photography, showing the work to the people I was photographing, helped me identify with people and learn Portuguese. At that time, I met the famous anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro, and he suggested that I go visit an indigenous village. I embraced the suggestion and went to meet the Karajá Indians. Later, I tried to show my work to the Brazilian magazines O Cruzeiro and Manchete. But they weren’t interested.

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Nogueira: Why?

Andujar: I was a foreigner, a woman who was messing with things she shouldn’t. I stayed with the Karajá twice, two months each time. Then I decided to go back to the States to show my photography and was well-received. I went to Life magazine, to the museums. I had tried in Brazil, but nothing had panned out. In New York, I knew the world of photography. But I didn’t want to stay in the States; I wanted to go back to Brazil.

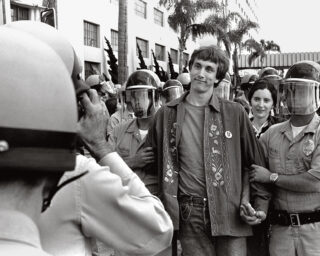

Nogueira: When you came back, you worked for the magazine Realidade (1966–1976), which was critical to the history of Brazilian photojournalism. the majority of their photographers were immigrants like you. What was it like there?

Andujar: The story of Realidade is special. The magazine’s journalists were against the military government that took power in 1964; they looked for stories that spoke of the difficulties in Brazil. I did well there because the places I went were always places with people who were in some way oppressed by the political situation.

Nogueira: You photographed stories on the erotic theaters in downtown São Paulo, childbirths, prostitutes in the countryside. What moved you?

Andujar: I was the person the magazine could always send to shoot in difficult places. I always sought out people on the margins. I wanted to get into people’s souls. Later I got interested in the spiritualist medium Chico Xavier. There are things that to this day I don’t understand. I would almost say that he had a connection with shamanism. But it isn’t shamanism. He had a very strong spiritual life. The way he managed to do certain things—I can’t explain it. Once I photographed someone being cured of cataracts. He hypnotized the person, gained some power over her, and stuck a knife into her eye. A knife! A regular knife, to cure her. And he cured her, but I don’t know how this person kept quiet, leaning against the wall, and letting him do that. If I hadn’t seen it, I wouldn’t have believed it.

Nogueira: You were also exploring the city.

Andujar: Yes, my photos of Direita Street and those made with infrared film are from that time, but those weren’t for Realidade. I did those for myself. Before Realidade, I didn’t photograph in color.

Nogueira: You squatted on the ground to make the Direita Street photos. Did people find that strange?

Andujar: Well, they didn’t find it very common; they thought it was a little curious, but nobody messed with me. They got a kick out of my attitude, that’s for sure.

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

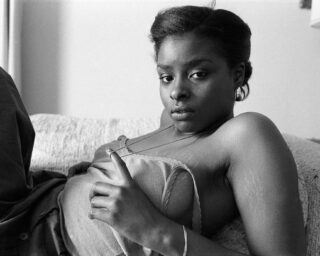

Nogueira: Your 1970s work has a visual freedom that’s rare for someone who worked for the press—the infrared film, the dislocated point of view, or even when you rephotographed slides, like in the photos of Sônia. Where did that experimentation come from?

Andujar: I would say that it was my contact with George Love, my second husband. He was interested in new angles, new ways of photographing. But even with these new techniques, I still maintained a humanist vision, don’t you think?

Nogueira: You once took a model and magazine crew to do a fashion shoot in an indigenous village. How did that come about?

Andujar: In the 1970s there was a fashion magazine called Setenta, for which I did various jobs. I suggested a fashion piece with the Xicrin Indians, which Setenta published.

Nogueira: You were criticized severely for this piece, weren’t you?

Andujar: I was—an anthropologist said I had gone to the Xicrin to show that they were inferior. For me it was nothing like that. I wanted to show that the Xicrin had their own style, their own inventiveness, that they were creative. But everyone has their own interpretation.

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

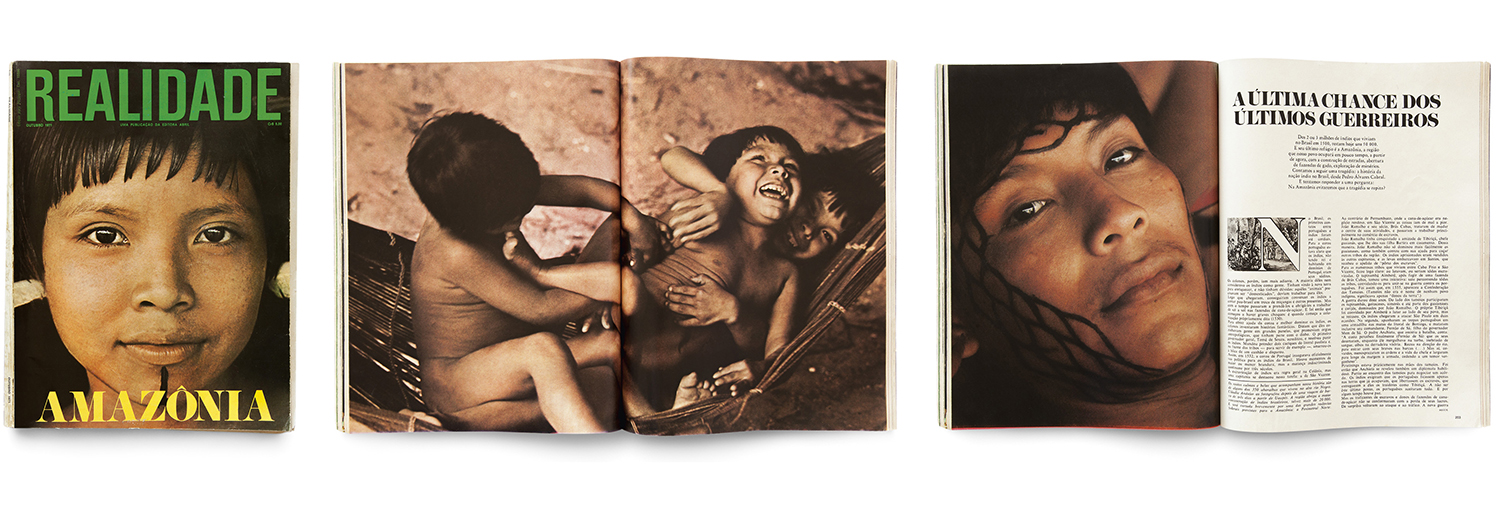

Nogueira: In 1971, Realidade did a special edition on the Amazon. Why were they interested in the region?

Andujar: The Trans-Amazonian Highway was being built; an American had bought all this land there. When I went to photograph, there was so much deforestation going on. It was a disaster, but the Brazilian government allowed it to happen. They said that the Amazon was an empty space that had to be developed. The magazine was interested in showing what the Amazon was like at that time.

Nogueira: Was it then that you made your first contact with the Yanomami?

Andujar: Yes. When I went to photograph in the Amazon, they asked me not to photograph the indigenous people because the Brazilian government was mistreating them. It was a type of government repression. But after I had been there for some time, I found out that a priest had died suddenly, and nobody knew how. I asked the magazine if they would be interested in this story. They said yes. So I went to the Yanomami. I never found out why the priest died, but I photographed the Yanomami. I liked them a lot, and in the end the magazine published many pages and put one Yanomami on the cover. The Yanomami hadn’t received any Western influences yet; they were first-contact people. The magazine accepted the story … and we all forgot about the priest.

Nogueira: Realidade had a short life span, did it not?

Andujar: After the special edition on the Amazon, they started letting people go. The whole office was fired for political reasons, because all of us were leftists. I decided to leave and no longer work in photojournalism. I decided to go deeper into the question of the Yanomami.

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Nogueira: So you went on to photograph them regularly, as an ongoing project?

Andujar: I tried to penetrate the Yanomami culture. I wanted to understand their beliefs, social practices, shamanism. I began this work in 1971. Later, in 1974, the government began the construction of the Northern Perimeter Highway, the second longest roadway in the Amazon. I was there when it began. And it changed me profoundly. I saw hundreds and hundreds of people dying. These people had no immunity to the diseases that were suddenly brought there. And, because of that, I decided to dedicate my life to their lives and culture.

I tried to show the shamanism, which is essential to their culture. And I explored the contact and the harm this brought to these people, which was sickness and death. I used color a lot, and double exposures. I thought that I had found a kind of visual expression that referred to the culture.

Nogueira: Therein lies the beauty of the work. You are always experimenting with visual language to deal with cultural questions.

Andujar: That’s right.

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Nogueira: What was your routine in the village like? Did you take special precautions?

Andujar: In the beginning, they didn’t know what photography was. When they first saw it, they didn’t recognize themselves. With time I believe they will refer to the images I took of them as a reference to their past, their cultural heritage. But I think that to this day, it still isn’t totally clear to them. I never photographed anything they didn’t want me to. The death rituals, for example. They thought that through photography something of the person was stolen. In their funeral rites, they destroyed and burned everything that linked the person to his life, to free his soul so he could live for eternity. That included burning the photographs.

Nogueira: You received many grants to continue the work, including two from the Guggenheim, but in 1977, together with foreign anthropologists and researchers, you were taken by force from Yanomami lands. What happened there?

Andujar: I was ousted by the Brazilian government. They didn’t understand what I was doing there. They thought I was trying to show how the government was mistreating the Indians. That I did this to show to people abroad, that I was some sort of spy.

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Nogueira: You’ve said you are not convinced your work in photography has been the most important thing you’ve done to date. What do you mean?

Andujar: Photography is an eternal search for myself—a language. But the work of trying to understand the life and the culture of a people is much more than photography. Photography is part of that, but not everything. One day we asked the Indians what art was for them. And they said we make our categories, and one of them is art, but for them it is not the same. Photography has brought me many things, but the survival of the world, of humanity, is something we struggle for constantly.

Nogueira: Do you see a parallel between your story and that of the Yanomami?

Andujar: Yes, I do, of course. I lost my whole family and I always think my relatives were marked to die. I’ve learned so much from the Yanomami. We are destroying nature, destroying life. The Indians consider themselves part of this totality of nature, the human being as part of the whole. If you destroy any part of the whole, you destroy the world. That’s why I did the photo of the end of the world in the series Sonhos Yanomami (Yanomami Dreams).

This piece was originally published in Aperture, issue 215, Summer 2014.