The Cotton Bowl and the Super Bowl

Coinciding with Aperture magazine’s “Vision & Justice” issue, students in Sarah Lewis’s Harvard University class “Vision & Justice: The Art of Citizenship” contributed essays on the relationship between images of social unrest and landmark Supreme Court decisions. Here, Eli Wilson Pelton reflects on Hank Willis Thomas and Dred Scott.

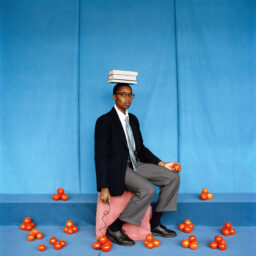

Hank Willis Thomas, The Cotton Bowl, 2011

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

How can one be free but not a citizen? This is the paradox that the Supreme Court codified with the 1857 ruling of Dred Scott v. Sandford, which declared “a negro, whose ancestors were imported into this country, and sold as slaves,” was “[not] a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution” and therefore ineligible for citizenship, whether free or enslaved. This is the paradox that continues to manifest itself within our contemporary American landscape. The Dred Scott case reiterated citizenship as a contested site predicated on the body, one not found in the body’s relation to its surroundings, but in the very body itself. Dred Scott made explicit, via legal history, that which was implicit in everyday life: to be a black American was and always will be a shifting gradient of citizenship negotiated through the body.

Hank Willis Thomas’s photograph The Cotton Bowl, part of his 2011 series Strange Fruit, makes this legal history legible through the great American congregation that is football. His digital c-print closes the historical and imaginative gap between two fields familiar to black Americans: the cotton field and the football field. Two black male bodies, their faces obscured by a straw hat and a football helmet, respectively, face each other in similar poses: the slave crouching to pick cotton and the football player crouching as he waits for the ball. The anonymous bodies are mirror images of each other, strung like paper dolls against a jet-black background, and suspended in an environment of atemporality, spectacle, and artifice. The photo traces the lineage of black bodies as commodified tools of profit, and maps the genealogy of black ownership: yesterday it was massa, today the NFL. The figures’ anonymity reinforces their status as objects reduced to bodies and re-inscribes history on contemporary football parlance (players are bought, branded and traded, scorecards and stats are kept, chain gangs are made).

In interviews, Thomas makes clear that the field in The Cotton Bowl is intended to represent twentieth-century sharecropping instead of slavery, and is a greater rumination on “exploitation” and “spectacle.” His insistence on distinguishing between sharecropping and slavery points to his belief in the continual seepage of the historical past: black exploitation did not end with slavery, but continued with sharecropping, lynching, and redlining, and continues with the NFL, NBA, and police brutality. Thomas wants the viewer to imagine these legacies not as closed historical episodes, but instead as experiences on a continuum, shifting with time and always under constant, bodily negotiation. This is the paradoxical legacy of Dred Scott: freedom and citizenship continue to be a contested binary within the black body, regardless of the type of field.

Eli Wilson Pelton studies American history and literature at Harvard University.