The Biennale Embracing Fear and Ambiguity in Photography

Courtesy the artist

“Photography has come to symbolize the extremes of contemporary society,” writes author, curator, and artist David Campany in the introduction to The Lives and Loves of Images, a series of exhibitions he has organized for the 2020 Biennale für aktuelle Fotografie in Germany, on view across museums in the cities of Mannheim, Ludwigshafen, and Heidelberg. “It is deeply personal, and yet thoroughly public. Freeing at times, yet also limited and limiting. Expressive, yet culturally dominant. Pleasurable, but worrying. There is affection for photography, and it is a source of great fascination but we are, or ought to be, suspicious of its power and manipulations.”

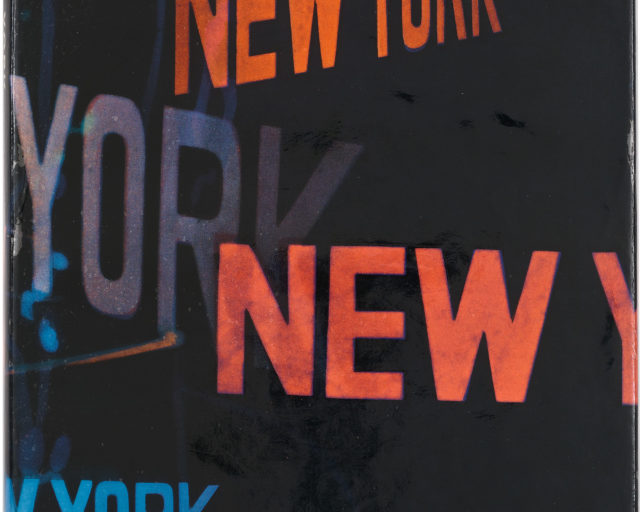

The biennale features more than fifty image-makers—including Stephen Shore, Vanessa Winship, Max Pinckers, Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, and Sohrab Hura—whose work is included throughout six exhibitions. In Reconsidering Icons, artists take on classic images; in All Art Is Photography, they consider art institutions and mediums; and in Walker Evans Revisited, they work in the spirit of the great photographer, or riff on his images. When Images Collide includes work using more than one shot, and Yesterday’s News Today looks at rescued news photographs, while Between Art and Commerce explores the boundaries between commercial, editorial, and fine-art photography. Ahead of the opening on February 29, writer Diane Smyth met with Campany to discuss the many themes of his ambitious biennale.

Courtesy the artist

Diane Smyth: I just had a look through the catalogue for the biennale, and I realized how big it is.

David Campany: It is big! It just so happened that when the organizers asked me to do it, I had half a dozen ideas for shows rattling around in my head. I think if I’d had nothing in my head, I would have said no, because it would have been terrifying. But the first thing to do was go and see all the venues and think about how the exhibitions might work in them.

Smyth: I can see why you had the Walker Evans show, Walker Evans Revisited, rattling around in your head, as you’ve done a lot of work with him.

Campany: That’s true, but what interested me about him was two-pronged. One thing was, why him out of all of those twentieth-century figures? Why is he still so influential? Then, he was quite prescient in a kind of thinking that concerns so many photographers today, which is that it’s not enough to just make the images. You’ve got to take care of how they get into the world.

Smyth: Was that the exhibition you had most clear in your mind to start with?

Campany: No, that was When Images Collide, because I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about image editing. I’m always swinging between thinking of photographs as rather individual, isolated things, and as bodies of work. So I thought it would be interesting to do a show that took the diptych as a starting point, because you can argue that that’s the start of image editing.

Courtesy the artist

Smyth: Did you have lots of artists in mind already?

Campany: Yes, my projects always come out of artists or particular works that have lodged themselves in my mind. I’m led by the works. Suddenly, I get a constellation of things in my mind, and I start to wonder: Why have these things stayed in my head? What’s the hidden logic that has allowed them to circle around each other?

Smyth: That’s interesting, because some of the works fit into one show in the biennale but could have been argued into another.

Campany: It’s true, and there are also a number of artists who are in more than one show. That was quite deliberate, because I think there’s a terrible problem with the way photographers get pigeonholed now. The contemporary approach you’re supposed to take is to do something very distinctive, but I think the richest period in photography was the 1920s and ’30s, when so many photographers could do anything. The field was wide open. Why can’t you be a great photojournalist as well as a very interested architectural photographer and still-life photographer and fashion photographer? Why can’t you appear in the avant-garde journals and the mainstream press? That seems in the nature of the medium.

Smyth: That makes me think about the willingness to keep experimenting. You write in the catalogue essay about Walker Evans using the new wide-angle lens on his Contax to take the subway pictures.

Campany: Totally, he used every camera and format going; he never really fixed his attitude toward the medium or his understanding of it. I’m interested most in photographers who are interested in renewal, in the idea that you could start again somewhere else.

Courtesy Hein Gorny—Collection Regard, Berlin

Smyth: Like Broomberg and Chanarin? They’ve used virtual reality for the piece they’re showing, Woe From Wit (2018), which takes as its starting point a controversial, World Press Photo–winning image by Burhan Ozbilici, showing the murdered Russian ambassador to Turkey, Andrei Karlov, and his assassin, Mevlüt Mert Altıntaş. The work is part of Reconsidering Icons.

Campany: Yes, they embody something in the heart of the biennale, which has to do with this balance of feeling a certain kind of fascination and affection for photography, and also feeling very suspicious of and dubious about it.

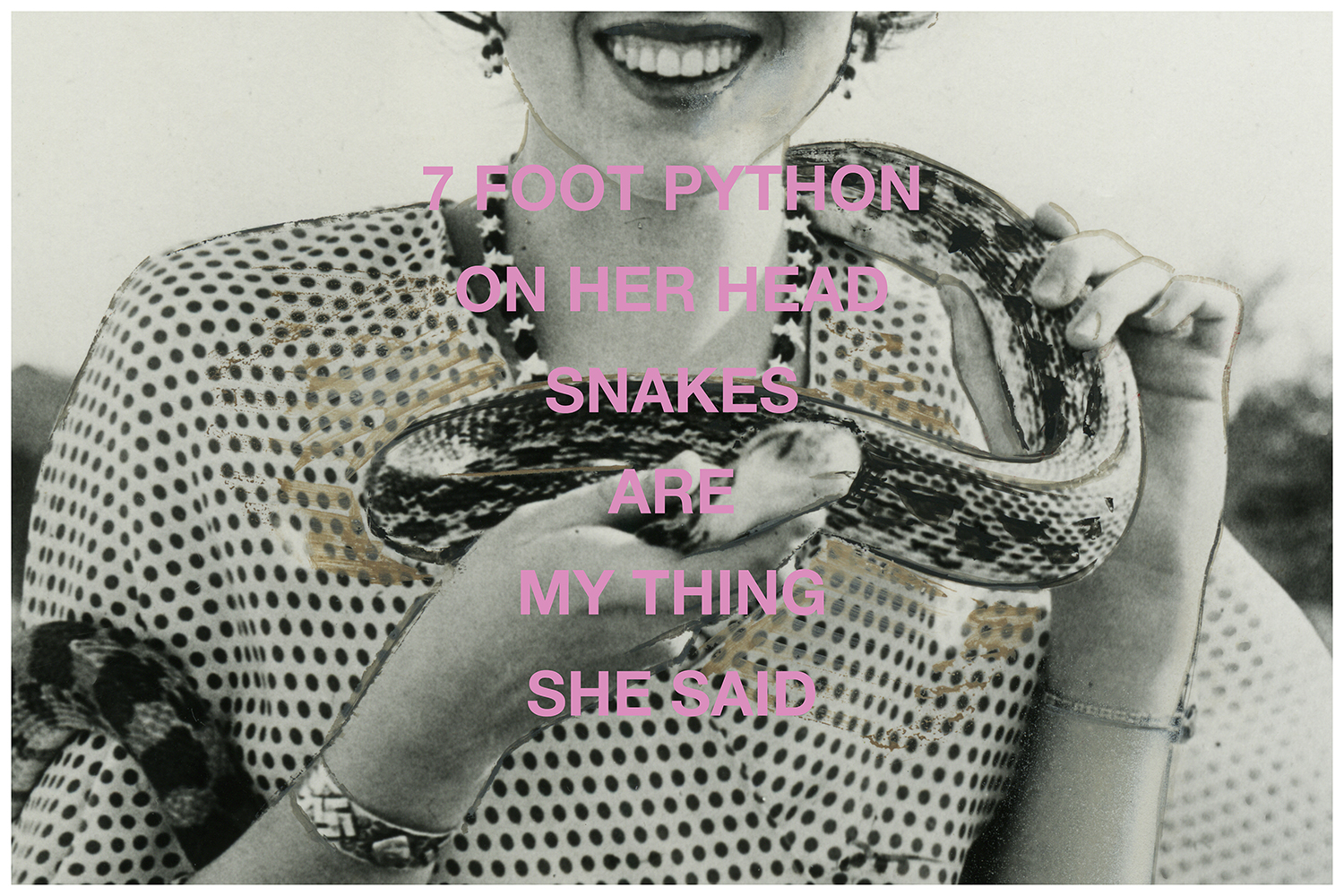

People are deeply frightened of photographs, I think, because of their ambiguity. People want to know that an image is coming from a good place—when it’s disturbing to them, they want to know that the photographer was well intentioned. But sometimes, the most significant images don’t come from a good place. Art doesn’t necessarily come from a good place. It might be contradictory, or an artist might not necessarily have a clear view of things.

When I was writing the catalogue, I was trying to take out as much writing as possible. If these images are well chosen and well sequenced, they’ll do most of the work, and they’ll leave that ambiguity open.

Courtesy the artist

Smyth: And likewise, the exhibitions will be shown with even less information?

Campany: There will be a brief introduction and sometimes, there will be a little bit of information, enough to be a key to open something. But there’s a fine line between writing that’s a key to opening something and writing that slams the door in the face of ambiguity.

Photographs have a way of covering their traces—when you look at a photograph, it’s often hard to know how it was made or why it was made, and that produces an anxiety. So people often want to know that and think that that’s the meaning. I am deeply suspicious of that. John Cage had a nice expression; he called it “response ability,” the freedom to respond, but also a kind of obligation to bring what you can to it.

Smyth: So it’s a bit lazy to want to be told what to think?

Campany: Well, it’s debilitating. I like it when people have radically different opinions about images; there’s something utopian about that. It’s like, OK great, we’re away from the tyranny.

Smyth: This makes me think of something else you’ve written in the catalogue, about images that were first used one way but which artists have reused in another way, the idea that there’s no definitive understanding of the image.

Campany: That’s partly why the biennale title has the word lives in it, because once one accepts that images don’t have meanings, they have potential to mean, and once one accepts that there’s no home for photography that is not legitimate somehow, you then have to accept that an image is going to have a life. It might have a short one; it might have a very long one. And if it’s long, it’s going to be unpredictable. It’s not going to mean the same thing through history and across contexts.

Courtesy the artist

Smyth: Do you see the exhibitions as very separate from each other, or interrelated—in that they’re all relating to the form or context of photography?

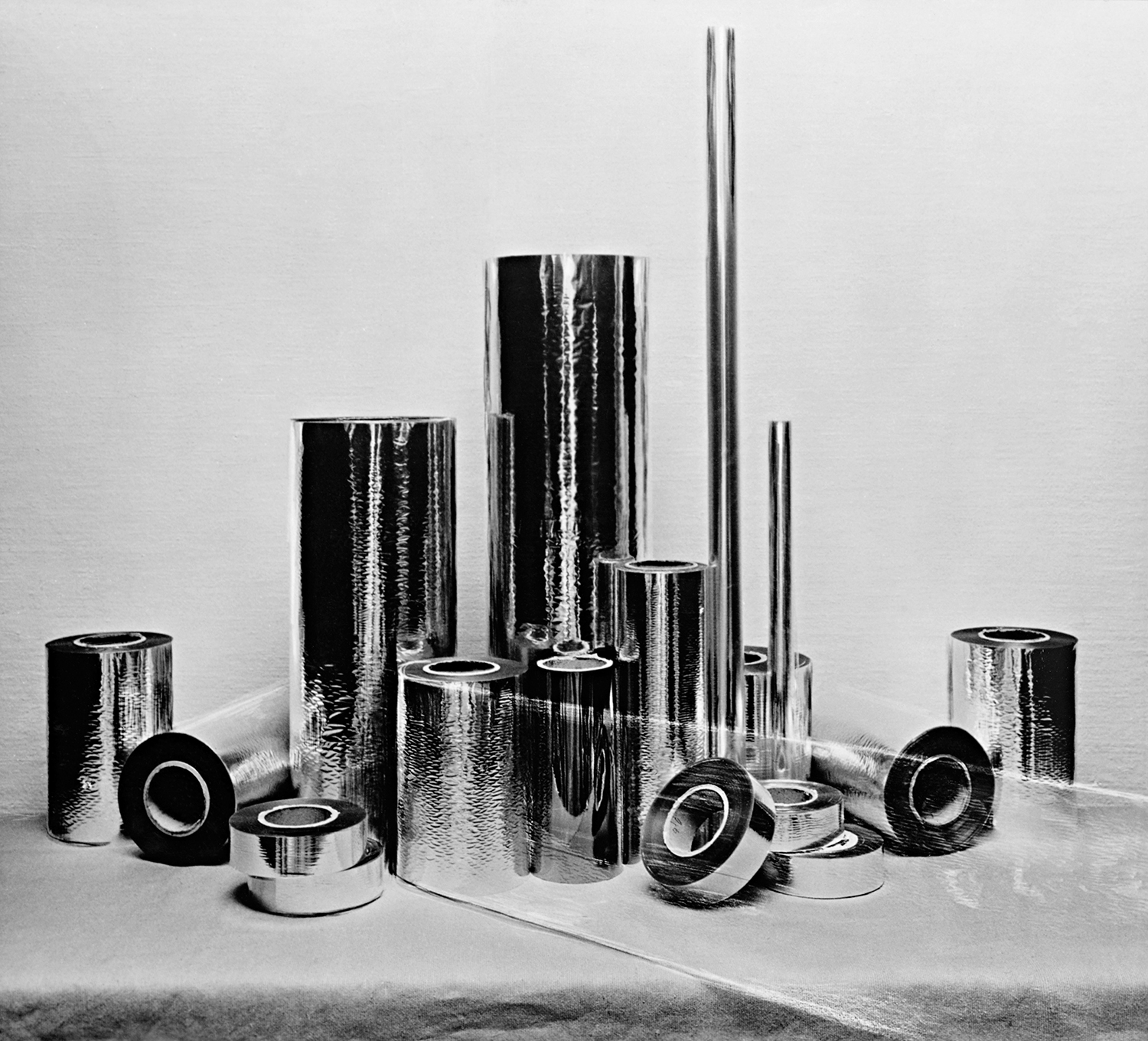

Campany: They are [interrelated], and yet they’re all very visually distinct, and they will all have their own logic. There’s a show called Between Art and Commerce, for example, which looks at that 1920s, 1930s legacy, in which the most interesting avant-garde photographers were also the most highly paid commercial photographers. That show is quite playful; it’s trying to keep the audience on its toes. One of the photographers, Daniel Stier, works commercially, editorially, and for fun, and he will be presenting his pictures without telling the audience which is which. They’ll just have to think for themselves.

I guess with a biennale, it should add up, but you do want each show to be its own thing. I talked to the organizers and they said, “Some people will see everything. Some people may see one show or two shows or five shows or six shows.” You can’t overprescribe that. You don’t know how something is going to be remembered—you don’t know what’s going to stick in someone’s mind and why. After it’s done, you hand it over to the audience, and they make of it what they will.

Smyth: But do you think that an interest in form can be disparaged? That people might say there are more important things to worry about at the moment?

Campany: I’m much more interested in how people think than what they think, because, in a way, the what will follow from the how. We live in an era of propaganda and counterpropaganda; it’s very difficult for any of the voices of sanity to make themselves heard. But given that an exhibition is by nature a slow space, I think you’re obliged to set up a space where response ability is more important than what that response is. In the end, you get a better society out of granting and encouraging people to think, not telling them what to think.

The 2020 Biennale für aktuelle Fotografie, The Lives and Loves of Images, is on view February 29–April 26, 2020, in Mannheim, Ludwigshafen, and Heidelberg, Germany.