Dorothea Lange and the Afterlife of Photographs

A new exhibition reveals how Lange’s concern for the dispossessed has never been more relevant.

Dorothea Lange, Migratory Cotton Picker, Eloy, Arizona, November 1940

In 1934, in the midst of an economic, agricultural, and environmental disaster that was actively devastating the United States during the long depression, Dorothea Lange abandoned her lucrative San Francisco portrait-studio practice to photograph the urgent and unfolding humanitarian crisis. Over the next ten years, working for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) and a variety of other government agencies, Lange produced some of the most powerful and influential social-documentary photographs of the modern era. Her photographs—and their distribution through government channels—gave a human face to indigent, outcast, starving, and forgotten laborers, often in the form of iconic images, such as her famous Migrant Mother (1936). Yet despite the evocative efficacy of her individual pictures, Lange claimed that, “All photographs—not only those that are so-called ‘documentary,’ and every photograph really is documentary and belongs in some place, has a place in history—can be fortified by words.”

Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Lange’s contention pinpoints a dilemma at the heart of all documentary photography: despite the tremendous evidentiary potential of the image to document historically specific effects and relations of power, it still relies on the inherently ambiguous medium of photographic realism, particularly when such photographs are decontextualized or uncaptioned. As German playwright Bertolt Brecht famously observed in 1931, a simple reproduction of the Krupp weapons factory tells us nothing about the labor relations of that workplace or its imperial significance. Seizing this classic modernist dilemma as its thesis, Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures, the stylish retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (currently closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, but reopening online this month), cleverly organized by curator Sarah Hermanson Meister, reconsiders Lange’s key photographs as formal solutions to this essentially political problem.

© The Museum of Modern Art

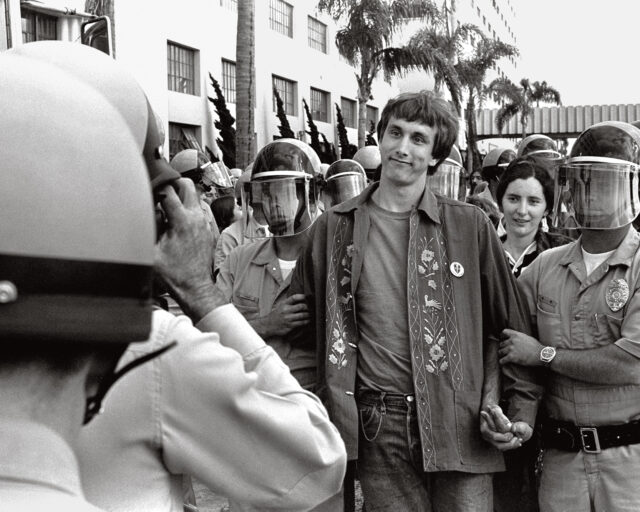

One of the first objects in the exhibition is a magazine, the leftist Survey Graphic, in which a reproduction of Lange’s heroizing portrait of a labor organizer speaking at a rally for strikers in San Francisco in 1934, dramatically shot from below, is given pointed meaning by the militant caption “Workers, unite!” This photograph accompanies a fiery article by Paul S. Taylor, a progressive economist at the University of California, Berkeley, with a deep knowledge of the history and economic structure of modern agricultural practices, from the tenant farms of the Old South to increasingly industrialized farming in California. Soon thereafter, Lange and Taylor married and began a years-long collaboration to produce books and field reports containing clear, factual information through data mining, research, interviews, travel, and photography. Lange became what her biographer, historian Linda Gordon, calls a “visual sociologist,” meaning that she brought to her documentary photography an almost scientific precision and an empathetic sociological interest in the lives and working conditions of the laborers and others she photographed and interviewed.

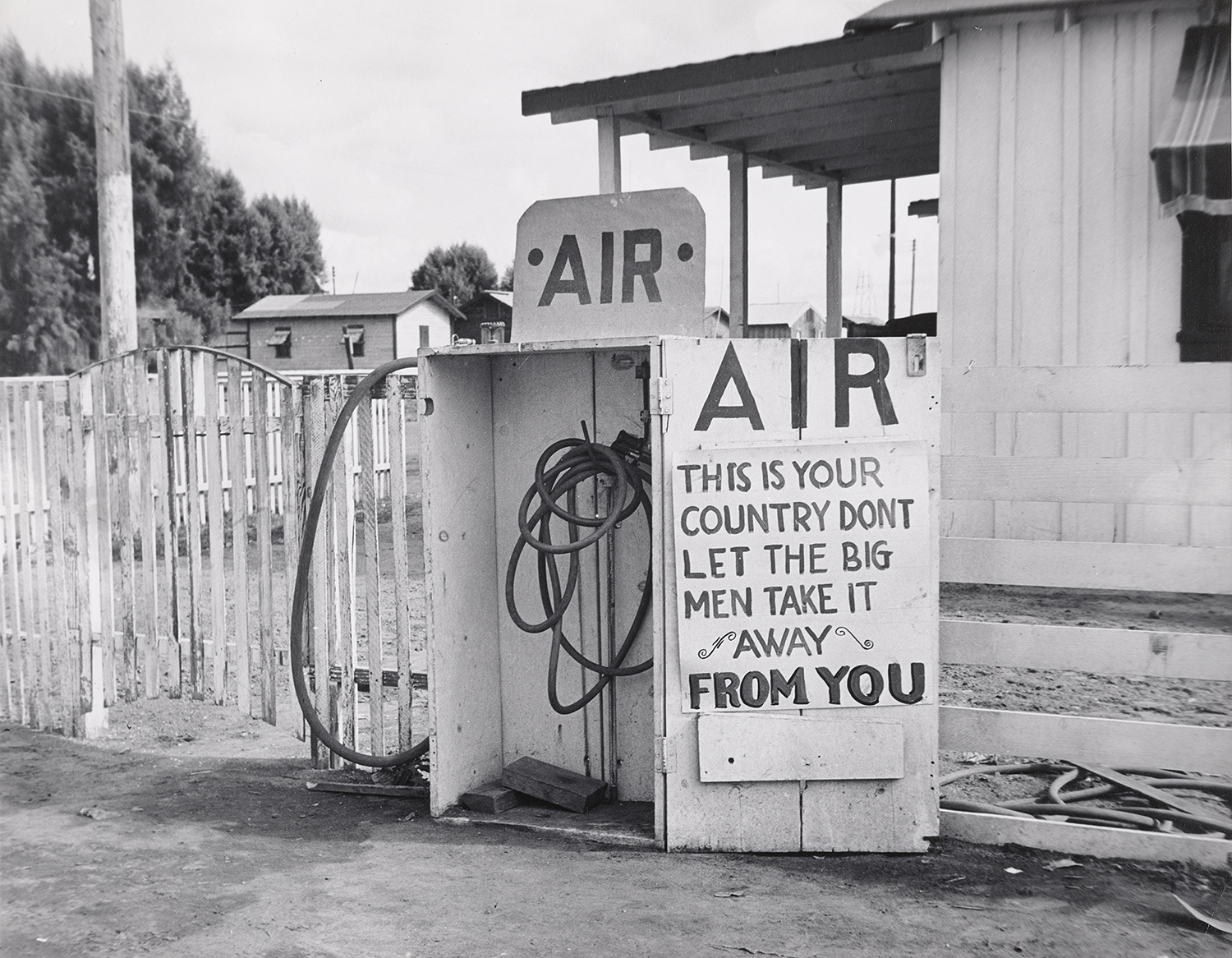

The environmental catastrophe of the Dust Bowl and the economic and health requirements of migrant farm laborers flooding into California throughout the 1930s formed the narrative of Lange and Taylor’s great documentary photobook An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion (1939). The book was compiled and designed by Lange and Taylor, and it traces their journeys crisscrossing five geographical areas of the United States. With Lange’s hard-hitting photographs, often close-up portraits of individual workers, and Taylor’s clear and passionate prose, An American Exodus made a radical case for establishing a systematic and sustained government policy on agriculture, with reforms based around the family-owned farm and cast in opposition to increasingly industrial-scale farm mechanization. In their introduction, Lange and Taylor outlined their activist strategy: “We use the camera as a tool of research. Upon a tripod of photographs, captions, and text we rest themes evolved out of long observations in the field.”

Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Formally, what is most radical about An American Exodus is how Lange and Taylor shaped their arguments through a sophisticated type of photomontage, an ingenious juxtaposition of many of Lange’s most dramatic photographs (though, surprisingly, not Migrant Mother) with an unexpected variety of primary texts—newspaper headlines, excerpts from government reports, and snippets of oral testimonies. Words & Pictures includes a rich selection of Lange’s photographs from this period, drawn from MoMA’s extensive collection. These pictures are emblazoned in our collective memories: workers in cloth caps and overalls, standing alone or in groups, looking stunned or lost; farm families of dirty and barefoot children piled into the backs of open pickup trucks; rows of fieldworkers hunched over roughly plowed furrows. But the real kicker in An American Exodus comes when one unforgettable 1938 image from Texas—showing a weary woman in a sack dress, her hand to her forehead, silhouetted against a sweltering sky—is captioned with words the woman spoke: “If you die, you’re dead—that’s all.”

With its rich and politically pointed collage of American farmworkers in distress, An American Exodus provides the most compelling proof of the idea proposed by Words & Pictures that words shape the effects of documentary photographs. Similar documentary photobooks were hugely popular internationally in the 1930s, often with highly innovative uses of graphic design and photomontage. But the American examples, like An American Exodus, are less well known and less commonly exhibited than those produced by avant-garde Russian or European makers. So it is a welcome intervention that this exhibition generously highlights not only An American Exodus, but also two other important American photobooks—Archibald MacLeish’s Land of the Free (1938) and Richard Wright and Edwin Rosskam’s 12 Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States (1941)—both extraordinary visual compilations which borrowed Lange’s photographs, though without her texts or direct involvement.

© The Museum of Modern Art

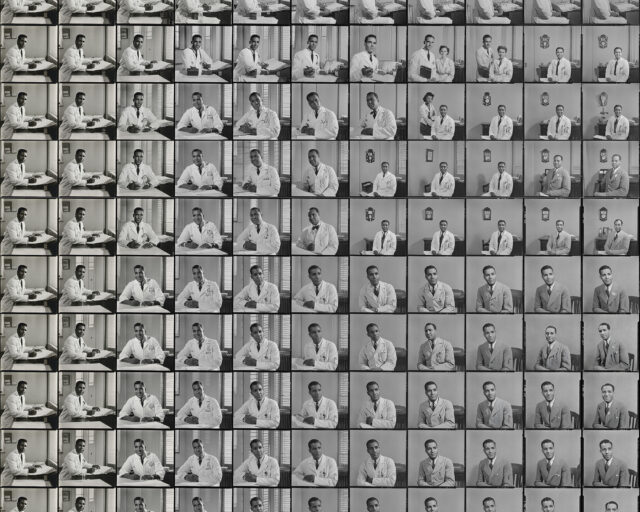

In considering the words that provide the politicized context for Lange’s work, Meister focuses primarily on what some have called the “afterlife of photographs”—that is, not the decisive moment of capture, but rather the subsequent uses of images, how they circulate and accrue new meanings, often well beyond the photographer’s original intentions. This perspective is particularly crucial for understanding Lange, whose best work was created for and controlled by U.S. government agencies, often in the form of propaganda, sometimes to the point of censorship. For example, as historian Nicholas Natanson has pointed out, while almost a third of Lange’s FSA photographs depicted people of color, the New Deal government agency, mindful of Southern social codes and the political power of white Southern congressmen, never distributed any of them. And her World War II–era images of the Japanese American evacuation and internment camps, taken on assignment for the U.S. Army’s Western Defense Command in 1942, were immediately impounded by the government and not published until 2006.

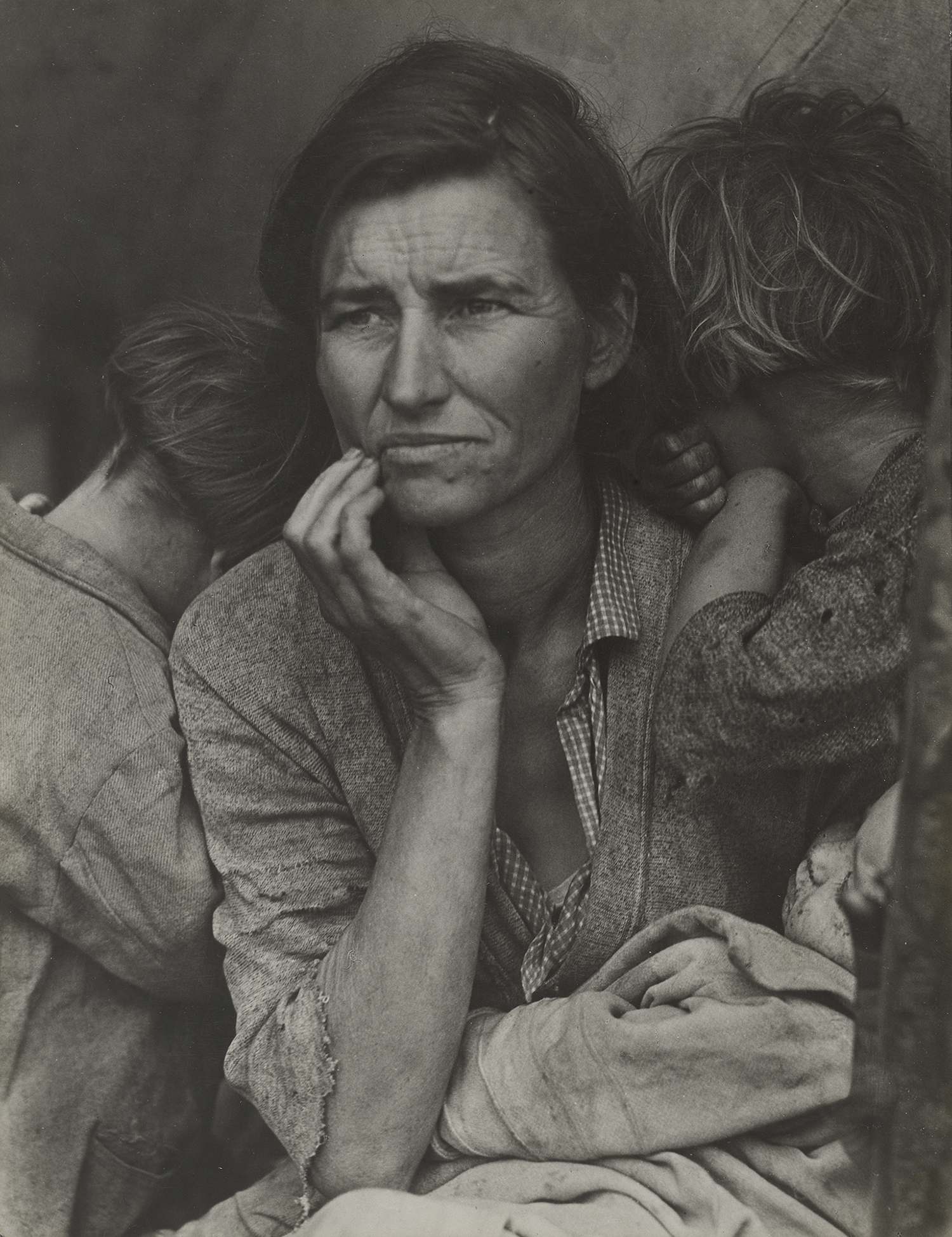

This blatantly propagandistic deployment of Lange’s photographs is often reflected in the shifting titles of her works, some applied by Lange (Damaged Child, 1936), but most not. Few photographs have been as transformed in their afterlife as Migrant Mother, which portrays an unemployed female pea picker and her children huddled in a makeshift tent in a laborers camp in Nipomo, California. Almost immediately, this portrait was recognized as an archetypal symbol of the impact of the blistering economic crisis, and it was published in halftone reproduction in national newspapers. Within days, the photograph was printed alongside a scathing editorial in the San Francisco News, which shamed the state of California for attempting to block the construction of government-sponsored sanitary workers camps. Echoing Lange’s own activist stance, the headline screamed, “What Does the ‘New Deal’ Mean To This Mother and Her Children?” The text continued, “Here, in the fine strong face of this mother . . . is the tragedy of lives lived in squalor and fear, on terms that mock the American dream of security and independence and opportunity.” Providing secure and sanitary living conditions for migratory farmworkers was one of Lange and Taylor’s pet projects—they succeeded in gaining a one-time $20,000 grant to build better facilities—but for the most part, even the reformist New Deal government ignored this need.

Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York

When originally published in the New York Times in 1936, Migrant Mother was captioned “A destitute mother—the type aided by the W.P.A.,” and in 1940, it was shown at MoMA as “Pea Picker Family, California”; the photograph was not given its lasting title until 1952. It was featured prominently recast as a symbol of eternal motherhood in curator Edward Steichen’s magisterial 1955 MoMA exhibition The Family of Man, and much of its subsequent sentimental mythologization depended on that presentation and on the photographer’s own hazy recollections, as spelled out in two prominent magazine articles exhibited in Words & Pictures, one by Lange and one by her son, Daniel Dixon.

More recently, Migrant Mother has been the focus of substantial critical attention, much of it focusing on the afterlife and recontextualization of the image. It is the subject of a small, separate monograph by Meister, published by MoMA, and a lengthier scholarly examination, published last month, Migrant Mother, Migrant Gender, by photo historian Sally Stein. As these studies show, following the popular circulation of Migrant Mother as a “Dust Bowl Madonna,” scholars have uncovered the real person behind this previously anonymous symbol of universal suffering, Florence Owen Thompson—not a Nordic Okie or universal everywoman, but a Native American pea picker with ten children, driven west in search of backbreaking labor and forced to shelter in a roadside lean-to in a camp with 1,500 other indigent farmworkers. For years, the migrant mother’s identity as a full-blood Cherokee was masked by racial fantasies and misrepresentations.

Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Words & Pictures also provides a useful perspective on the limitations of the classic photo-essay, especially as deployed by LIFE magazine during the 1940s and 1950s (itself the subject of an enlightening exhibition at the Princeton University Art Museum, New Jersey). The brutally reductive photo-editing style of LIFE and the magazine’s right-of-center politics tamped down the progressive political slant of Lange’s photography. Though she focused almost exclusively on photo-essays from 1945 to 1960, she had difficulty mastering the blunt requirements of LIFE; all but two of her six commissions for the magazine were rejected. One of the successful ones, part of an extensive sociological study done jointly with Dixon, was called Irish Country People (1955). The other, produced in collaboration with Ansel Adams, was titled Three Mormon Towns (1954) and featured thirty-five images—a lot for LIFE—but only a fraction of Lange and Adams’s 135-image layout. The MoMA exhibition boldly exhibits every page of these stories, and it is clear what happened: while Lange was interested in the complex communal life of isolated, self-sufficient, almost utopian villages, the LIFE magazine machinery used nostalgic subheads (“Serenely they live in age-old patterns”) to turn them into sentimental pap. As Adams lamented, “The Mormon story turned out very sour indeed.”

Unfortunately, more often than not, Lange had little control over how her photographs were distributed or presented, and her own views on the subject of contextualization shifted. Lange’s images were repeatedly wrenched from their original contexts and accompanying voices, particularly by museums. As Meister shows through numerous MoMA installation photographs, Lange had a long and complex relationship with MoMA, beginning with the photography department’s inaugural exhibition in 1940. Over time, Lange came increasingly to regard her photographs as autonomous artworks, accompanied by descriptive captions and poetic texts. Lange was instrumental in the formulation of Steichen’s exhibition The Family of Man, for which she was an informal associate curator. The exhibition’s initial proposal included a long list of keywords (“birth,” “death,” “pestilence,” “conflict,” “peace”) and solicited photographs that would “reveal by visual images Man’s dreams and aspirations, his strength, his despair under evil.” As Steichen’s West Coast advisor, Lange suggested potential photographers as well as additional texts and thematic categories. But the Cold War–era exhibition tried to make its political points regarding the universal nature of certain human traits through a photo-magazine-style layout, with juxtapositions of large photomurals, mounted and unframed photographs, and allusive texts, including quotations, religious citations, proverbs, and folk songs.

Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Subsequently, Lange seems to have advocated a more abstract attitude toward her photographs, including her earlier reformist ones. For Lange’s 1966 retrospective at MoMA, organized by the young curator John Szarkowski, her photographs were arranged thematically rather than chronologically and, again, presented large and unframed, as more traditional artworks, with no wall labels and largely devoid of explanatory historical context. Looking at old installation photographs of that exhibition (online or in the Words & Pictures catalogue), we see Lange’s brutal photographs, like Migrant Mother and White Angel Bread Line, San Francisco (1933), aligned like so much black-and-white formal imagery, removed from their original advocacy. In a letter to Szarkowski in 1965, Lange stated that she wanted the captions to “carry not only factual information, but also added clues to attitudes, relationships and meanings.” About half of that 1966 retrospective comprised photographs from the last ten years of Lange’s life—more formalist images of trees, gardens, family members, and hands—with fewer and fewer words.

This is the fundamental dilemma Words & Pictures seeks to overcome. By acknowledging the interdependence of what artist Martha Rosler calls “two inadequate descriptive systems,” the exhibition aims to reunite Lange’s powerful pictures with their original political rhetoric. But amid the elegance of the exhibition design and the sheer artiness of the large, framed photographs, it is hard for viewers to reconstruct the filthy and intolerable conditions that Lange’s subjects endured and the contested politics engaged in fighting for justice, what she called “the big story which is behind it, which is the story of our natural resources.” Seeing these same photographs today, even in this provocative exhibition, we cannot help reading them as stolen gestures, misused and misinterpreted, or regarding them as valuable trophies in the context of today’s runaway market for vintage photography. (A vintage print of Lange’s White Angel Bread Line sold at Sotheby’s in 2005 for a record price of $822,400.) Blunting the edge of Lange’s content with an overriding emphasis on style and photographic beauty, Words & Pictures fits the apolitical through line of MoMA’s recent revisionist expansion. Like a lot of the museum’s new galleries, this temporary exhibition tries to overturn the museum world’s long-standing sexism by celebrating a female artist. But at the same time, it struggles to identify—much less harness—what made Lange’s bold work such an awkward fit in an art museum to begin with: her deliberate sociological investigations, her idealistic and tireless visual activism, the sharp feminist critique embodied in all her work.

Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Lange’s relevance could hardly be greater today. The themes she addressed—environmental blight, enforced migration, economic division, exploitation of labor, ingrained racial discrimination—are perhaps even more obvious and more contested now than in Lange’s lifetime. And yet, focusing on Lange’s formal juxtaposition of words and pictures, and by reprising Lange’s historical engagement with successive generations at MoMA, this exhibition inadvertently downplays the immediacy of Lange’s themes and portrays her as a onetime political activist whose photographs were gradually drained of their meaning and force, and an increasingly style-conscious artist who acceded to the poetic reinterpretation of her powerful images in museum settings. Read in reverse, Words & Pictures provides an exemplary case study of the way museums are complicit in stripping devastating pictures of their once-urgent words, and hence of their politics.

Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures opened on February 9, 2020, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The museum is currently closed, but an online version of the exhibition opens April 30 at moma.org.