How Can Photojournalists Navigate the Crisis of Press Freedom in Mexico?

Mexico is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist. In this conversation, moderated by Alexandra Ellerbeck, photographer Emmanuel Guillén Lozano and journalists Alejandra Ibarra Chaoul and Ginger Thompson discuss the current state of press freedom in an era of monopolized truth.

Emmanuel Guillén Lozano, A group of armed men standing in the field in Michoacán, southern Mexico, where the war against the cartels was declared by Felipe Calderón in 2011. Since then, the state has gone through an uninterrupted period of violence by the presence of drug cartels, the army and other groups of armed civilians, 2014

© the artist and courtesy the Bronx Documentary Center

Alexandra Ellerbeck: I’d like to start with Emmanuel. You’ve given your project a very bleak title, Blackness, and you document some pretty chilling things. What led you to look at the impact of the war on drugs in Mexico?

Emmanuel Guillén Lozano: We are presenting the work of three photographers, Mauricio Palos, Félix Márquez, and myself. Mauricio Palos focuses on following some journalists across Mexico to show how they work, under which kinds of circumstances. Félix Márquez documents the belongings of some of the journalists that have been killed in his home state of Veracruz. My work is a series of black-and-white pictures that tries to explore different parts of the country, following groups of sicarios [hit men associated with drug cartels] to landscapes interrupted by violence. I think it’s a pretty good combination because my work tries to show the environment itself and how violent it can be, Mauricio’s follows the journalists as they try to document what’s going on, and Félix’s focuses on the aftermath of covering those areas and of what happens to those who try to tell the truth in these places.

Ellerbeck: Alejandra, you’ve delved into press freedom in Mexico from a couple of different angles: looking at the factors that can lead to journalists being murdered, issues around impunity, crimes going unsolved, and now working on this database on journalists’ work. Can you give us a sense of the scope of the press freedom threat in Mexico and some of the findings of your research?

Alejandra Ibarra Chaoul: Mexico is a very peculiar case regarding press freedom because it became very violent as it transitioned into a democracy in 2000. I’ve done some work to explore what shapes the factors that result in violence against journalists, because it’s not only due to a general context of violence and the drug war—it also has a lot to do with corruption and lack of accountability from different levels of government. Mexico is the most dangerous country for reporters in the Western Hemisphere, and worldwide it can only be compared to countries like Iraq and Syria. As opposed to other countries, where reporters die in conflict zones and crossfire, in Mexico, journalists are targeted and they’re silenced for their work. They come for them while they’re driving their kids to school, when they are eating dinner out at a restaurant.

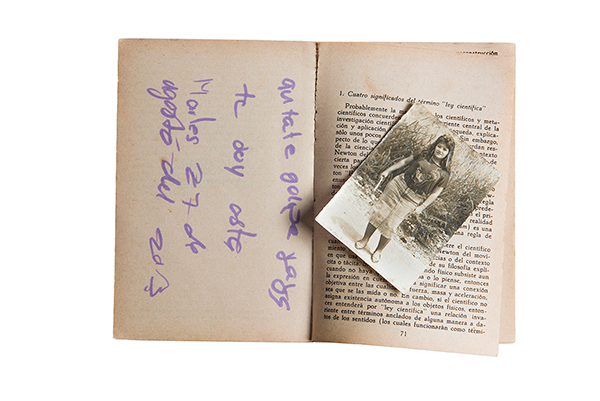

Félix Marquez, Property of Yolanda Ordaz, who was murdered July 26th, 2011, 2018

© the artist and courtesy the Bronx Documentary Center

Ellerbeck: Ginger, you worked in Mexico for more than a decade as a bureau chief. Can you talk about some of the challenges you’ve faced running a bureau in Mexico City and also, amidst this general panorama of violence against journalists—as well as against citizens throughout Mexico—what kinds of stories you looked to find for an American and international audience?

Ginger Thompson: When I was in Mexico, for the New York Times, the country had just elected its first nonruling party president [Vicente Fox]. We focused heavily on writing about him and his fight to establish independent institutions, particularly institutions that have to do with justice; it was a losing battle. The corruption in Mexico runs so deep and has been going on so long. Nine-eleven really derailed US interest in Mexico, so Fox suddenly didn’t have international support to push the politics of Mexico in a certain direction. The violence, though, didn’t really explode this way until after I had left Mexico and Felipe Calderón was elected president.

I didn’t start covering the drug war until I left Mexico in 2006 and I was in the Washington bureau. My focus on the drug war has been about the U.S.’s role, because I think a lot of the time, we in the United States think that this is Mexico’s problem. A lot of the problems have to do with Mexico’s lack of institutions and the corruption that runs deep there, but the U.S. plays a really big role in Mexico and in its drug war. In fact, when Felipe Calderón started the drug war, he started it with great support from the United States, which wanted to go after Mexican kingpins. The kingpin strategy has been ruinous for Mexico. Calderón basically started this war with the U.S.’s support, encouragement, and money, and forced this fight on institutions that weren’t quite prepared to protect civil society from the consequences. You’re running around arresting kingpins and disrupting criminal organizations, but there aren’t courts and police forces that protect civil society from the fights between drug traffickers that happen as a result of these big arrests. So a lot of my work has been about what role we play there, a role which is often kept secret because Mexico doesn’t want its people to know that our police, FBI, and DEA are operating in Mexican territory, and the US government wants to keep it secret for those same reasons.

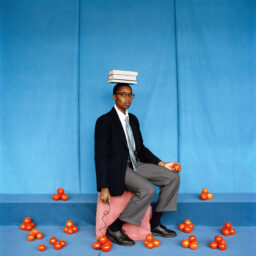

Mauricio Palos, La Ley del Monte, 2017

© the artist and courtesy the Bronx Documentary Center

Ellerbeck: Emmanuel, this is something that you actually touch on in your exhibit. You draw the legacy from the beginning of the drug war under Calderón in 2006 to the current administration of [Enrique] Peña Nieto. Could you give us a rough timeline of what’s happened over the past decade?

Lozano: Mexico used to be a really different country twelve years ago. Back in the day, the only narco-states were in places like Sinaloa and Chihuahua, but there were other places that were sanctuaries of peace. I can certainly tell you right now that there is not a place where there is peace, not even Mexico City. Felipe Calderón’s war continued till Peña Nieto took power in 2012. Peña Nieto’s administration decided to not change their strategy, and it was either a major mistake or a conscious decision, because everyone knew what was happening in Mexico. At the height of the violence during Calderón’s administration, the average number of people killed per day was fifty. In the middle of Peña Nieto’s administration, the average reached seventy people per day. In these past couple of months, the rate has increased to ninety people per day. Nobody’s talking about what’s going on there even though it’s worse than it used to be when it was being highlighted in the news. I think the figures are around 234,000 people killed and that’s the official number, so the real number might be way higher. Thirty-eight thousand people have disappeared in Mexico. Mexico finds itself in a very particular moment after the most recent election because for the first time, its federal government is shifting towards the left.

Ellerbeck: There’s a lot to dive into with the election and what that means for Mexico, but before we get there, you mentioned something that was very interesting, which is the idea that it’s actually in some ways worse now than it was in 2006. You said you thought that there was less coverage of that internationally. Ginger, do you find that to be the case?

Thompson: Yeah, I think the whole election went very uncovered in this country. There were something like 102 or 103 candidates for government—politicians—who were killed during this election season. The Times didn’t really write that story until two or three days until the election. I think there are a lot of reasons for that. This country is going through its own political upheaval and there are lots of places in the world to cover, but I think attention on Mexico has fallen particularly as we’re talking about journalists and the fact that it’s become the most dangerous place for journalists to work in this hemisphere. I think there’s been some good work on Mexico, but not nearly enough.

Emmanuel Guillén Lozano, A human skull lies on the ground next to a road in Coahuila, Mexico, 2015

© the artist and courtesy the Bronx Documentary Center

Ellerbeck: Alejandra, in this general environment where 234,000 people have been killed in Mexico, where does the issue of press freedom fit in? Why is the press freedom crisis something we should be focusing on amidst this general crisis of violence?

Chaoul: The patterns of violence against journalists vary according to what kind of threat you’re focusing on. If we’re talking about murdered journalists, the places where journalists are murdered are not always in states that are most violent. Of these crimes, 99.7% haven’t been solved, so we don’t really know who is murdering these journalists. None of these cases have come to a conclusion, nor is there a guilty party in jail. That makes calculating the risk for reporters really scary because if you don’t know where the threat is coming from, it becomes very complicated to assess when the threat is real and when it’s going to result in physical violence.

Thompson: Killing a journalist and killing anyone is a horrible thing, but in Mexico, when a journalist is killed, it’s an attack on democracy and it’s a message to civil society. That’s why these messages are important, because they have a political intent that is meant to quiet this effort by Mexican civil society to free itself from a seventy- or eighty-year-long rule by one political party.

Chaoul: I completely agree with you, Ginger. Journalists provide the information for us Mexicans to make better decisions, to choose our governors and representatives, and without that link, not only do journalists suffer, but the whole society suffers from the lack of information and agency to assert change and to hold people accountable.

Lozano: In Mexican society, but also in the rest of the world, there is a particular way of killing journalists. Sometimes they are shot in the street and that kind of thing, but there are also many cases of journalists being tortured before actually being killed. There is a particular signature of violence in each case that attempts to send a message to the rest of the journalistic community, especially the journalists covering stories in their hometowns. Local journalists are the most vulnerable of the whole community.

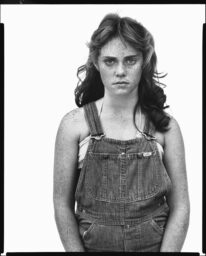

Félix Marquez, Property of Moises Sanchez, who was murdered January 2nd, 2015, 2018

© the artist and courtesy the Bronx Documentary Center

Ellerbeck: What kinds of stories are not being covered? What kinds of stories do some journalists maybe shy away from because of the threat?

Thompson: I think a lot of news organizations in Mexico have completely decided not to write about violent crime. They simply don’t cover every murder because a lot of those murders are committed by drug organizations that have control over the local government. These local journalists work in these news organizations where they have almost no pay. These news organizations run on advertising that comes from the government, so they are independent in many ways, but in the most fundamental of ways they are not. Editors are afraid to lose that financing, so they don’t want their reporters to report on stories that are uncomfortable for the government, which is in league with these drug organizations in many cases, especially at local levels.

I spent the last couple of years writing a story about a massacre in a town called Allende in Coahuila, where this massacre happened and dozens, possibly hundreds, of people just vanished and no one talked about it, for months. People were afraid to say anything to the police, because the police were involved, to the military because the military was involved, and to the mayor because the mayor was involved. I met a lot of reporters in Coahuila who said, “You know, I was there when Allende happened. We couldn’t report it. We weren’t allowed to report it.” Reporters who do, get killed, and they don’t just get killed, they get killed in front of their kids. They’re sending the message to civil society that “if we can kill her, this very public news person, if she has no protection, you don’t either.” And that’s why this is so insidious and why it’s so important.

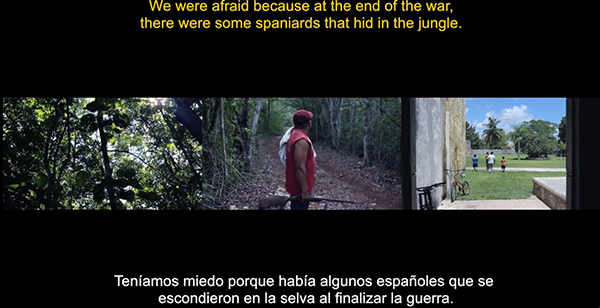

Mauricio Palos, La Ley del Monte, 2017

© the artist and courtesy the Bronx Documentary Center

Ellerbeck: Emmanuel, Alejandra mentioned how difficult it was to calculate risk and how difficult it is to know where a threat is coming from. You’ve had some of your own experiences navigating risk in your reporting. Could you tell us a bit about how you navigate that?

Lozano: It’s really hard to calculate the risk in Mexico. In some places in the world, there are really clear areas, red zones or green zones. Mexico is an entirely red or black zone, so you can’t know who is trustworthy. The military, the army, the navy, and the federal police—every single layer in Mexican society is involved at some level, so it’s really difficult to navigate. In my experience, I used to spend my vacations in college at these places just because I was curious about them. That was probably pretty stupid, but somehow I learned to navigate some of the places that I was going to. At some point, I started to get threats from the cartels. Even if you start receiving threats from the cartels, there might be a safe zone as long as you don’t go into their territories. As long as you don’t mess with them again, it’s probably going to be fine—not in all cases, but in my case it was.

What scared me the most was what happened after I covered the case of the forty-three students who disappeared in Ayotzinapa. It was published in a few places here, in the New York Times Lens blog, and in Europe. At some point, the nature of the threats I was getting started to change. I used to Skype with my girl, who’s my wife now. We used to Skype every day. We started to hear typing that was coming from somewhere—not from us, but from somewhere. We heard someone putting a glass of water on the table and other environmental noise that wasn’t from either of us. At some point you realize that these are not the cartels anymore, this is probably something else. I went to Mexico City once and they started to send me pictures of myself from earlier in the day. The nature of things is changing for me and for a lot of my colleagues. The government is more dangerous for some journalists than the cartels themselves sometimes. For most of my colleagues, there is no way to navigate those situations, especially when you’re living there.

Emmanuel Guillén Lozano, Smoke coming out from a “ghost town” in the mountain area of Guerrero, Mexico, 2010

© the artist and courtesy the Bronx Documentary Center

Ellerbeck: The Mexican government often talks about the press freedom crisis and about the general difficulty of dealing with organized crime. I’m interested in your thoughts on this excuse. How many of these threats are coming from organized crime? How many of them are coming from state actors? How should we even think about the dichotomy between those two?

Chaoul: Article 19 [a human rights non-profit that focuses on freedom of expression] investigates the source of some of the attacks, like hacking attacks or phone threats or cloning websites. According to them, most of these attacks come from public servants. Having said that, I think the line that divides the government from organized crime is way more unclear on a local level. At a municipal level it’s going to be way harder to determine which is which because they are the same. I think it gets more complicated with more elevated levels of government. When you’re talking about the federal government, it’s known that they’ve spied on reporters with malicious software. That’s where making the excuse gets harder, because it’s not really believable that they’re organized crime. Instead, they say it’s for security purposes.

Thompson: I think it’s actually not all that hard. What’s hard is to get people punished for those things. There’s plenty of evidence of collusion by high-level government officials at the federal, state, and local levels, but getting punishments for those people has been almost impossible. It is true, at the local level they’re the same people. At the federal level there’s maybe some degrees of separation. But the fact that the federal government has been hacking into reporters’ computer and phones, all of that has been proven. What’s really hard to get in Mexico is prosecution, and until that changes, the rest of it is going to be really hard to change. I’m not saying what Mexico needs to do is easy, because it’s not. A start might be prosecuting people at high levels who are responsible for these very prominent attacks on the press or on political actors, but I think there’s tons of evidence that the collusion is real.

Félix Marquez, Property of Guillermo Luna, who was murdered May 3rd, 2012, 2018

© the artist and courtesy the Bronx Documentary Center

Ellerbeck: I actually want to talk a little bit about this election. It’s hard to overstate how big of a deal this election is in Mexico. It’s a major shift, a major game changer. A left-leaning candidate, [Andrés Manuel] López Obrador, won the presidency and his party, Morena, won Congress and swept a lot of the local elections as well. So what does this mean? Are you optimistic that he could tackle issues like impunity, the lack of prosecutions of crime?

Chaoul: I’m going to choose to be optimistic. I think there’s a lot on the table that can work for passing certain laws that are key to protecting journalists. There’s enough strength in Congress and enough state congresses to pass and change laws. There are a couple of laws that come to mind. One is on internal security, which basically allows for surveillance against anything that seems like a threat, which could easily mean reporters. The other one, which Ginger mentioned, is one on advertising from the government. It’s an institutionalized way of exerting power and dictating editorial lines. That’s another one that could be changed. The numbers are there, it’s just a matter of if they’re going to do it.

Emmanuel Guillén Lozano, Bodies hanging from a bridge above the highway in Tamaulipas, Mexico, 2014

© the artist and courtesy the Bronx Documentary Center

Ellerbeck: I wanted to ask each of you what the international community should be doing to help resolve the press freedom crisis in Mexico.

Lozano: In the U.S.’s case, since we’re neighbors, I think we need more coverage on the context of the U.S.’s role in Mexico’s predicament, and more reporting on the major stories here. That’s all we need. That’s the least we can aspire to.

Chaoul: I agree with you but I would be a little more pragmatic. My wish would be for funding. Expand your Mexico bureaus, fund an independent, investigative newsroom. There’s really good reporting in Mexico, really good photojournalists in Mexico. Consume our stories, but also put some money there.

Thompson: I agree with both. I think having a way to hold bad actors accountable, as the press and as citizens who have senators and congressmen who send money to Mexico, is important. Obviously the one thing we don’t need is a wall. So in addition to what they’ve said: accountability and looking for ways to understand how interconnected we are, how Mexico’s problems are not just their problems, and how those problems are driven a lot by funding from or drug consumption in the United States. We’re in this together. I think if there was more consciousness about that, it would go a long way.

Alejandra Ibarra Chaoul is an investigative reporter, magazine writer, and researcher based in New York. Alexandra Ellerbeck is the North America Program Coordinator for the Committee to Protect Journalists. Ginger Thompson served as the Mexico City bureau chief for the New York Times and the Baltimore Sun. Emmanuel Guillén Lozano is a documentary photographer based in New York.

This conversation is adapted from a public talk at Photoville in New York on September 15, 2018, produced by United Photo Industries and presented in partnership with PhotoWings, with additional support by The Philip and Edith Leonian Foundation and Two Trees Management. This talk coincided with the traveling exhibition Attacks on the Press: Mexico, which was on view July 12–August 3, 2018 at the Bronx Documentary Center.