Erotic Voyeurs of Japanese Photography

Three celebrated photographers push the limits of sexuality and surveillance.

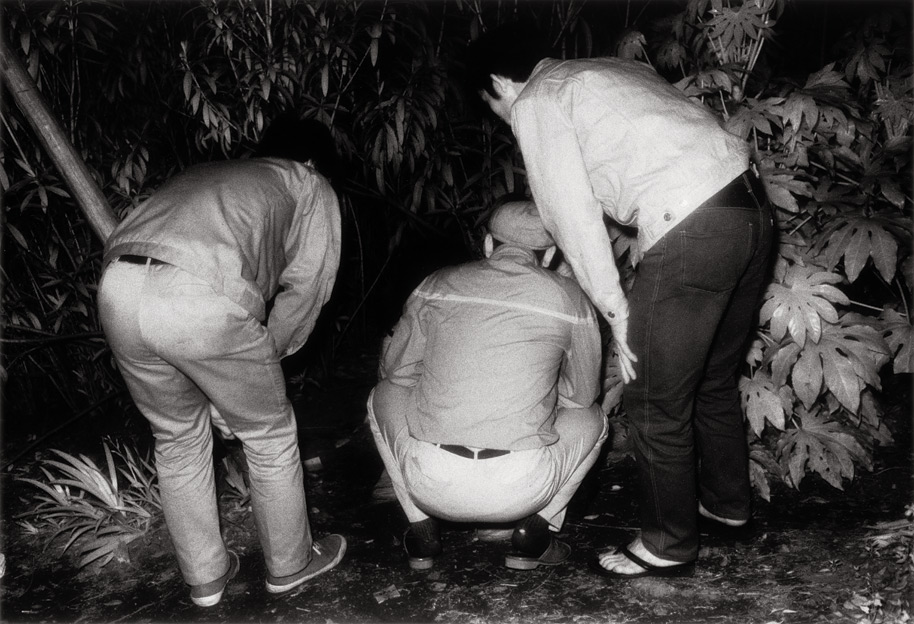

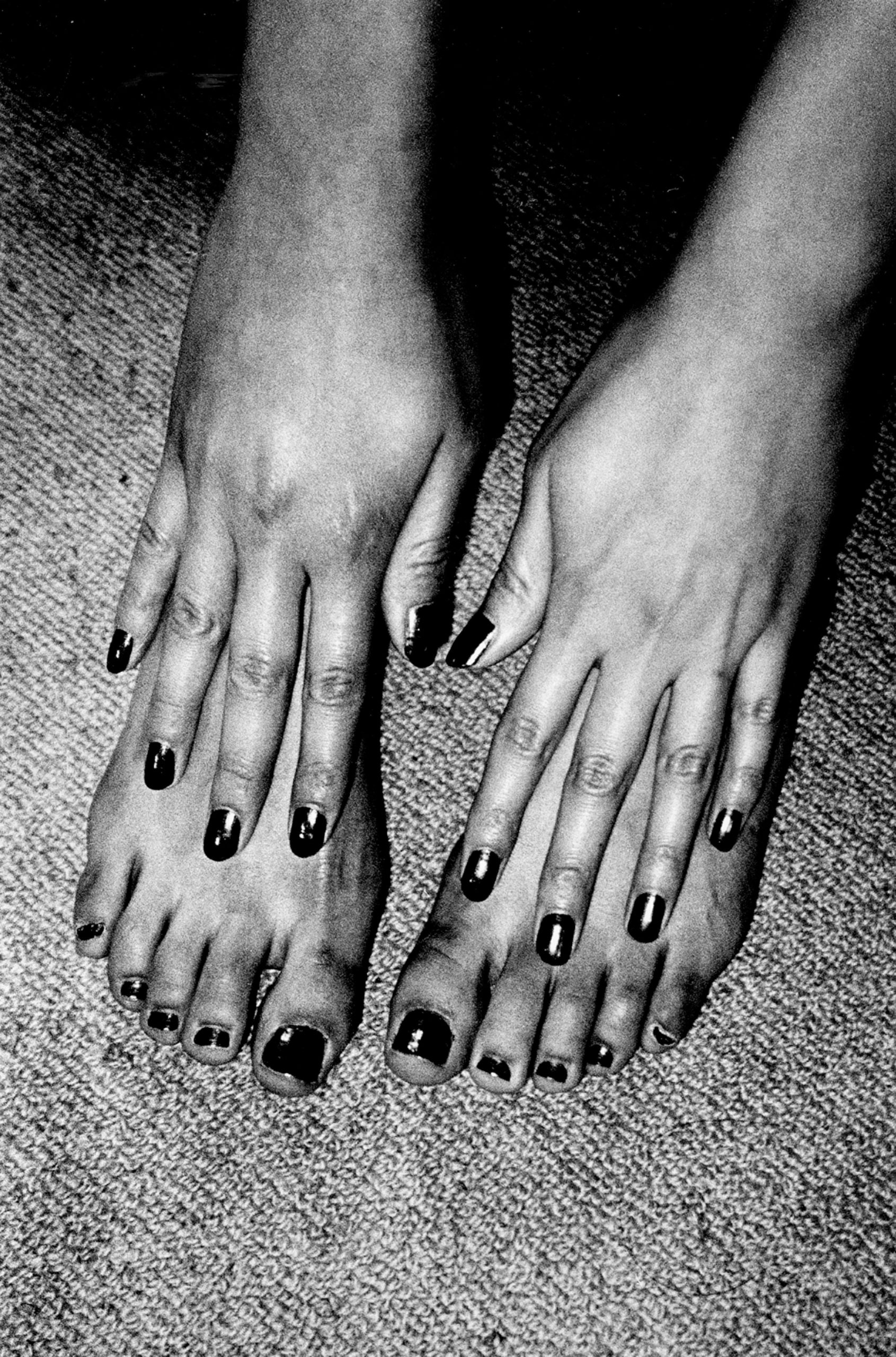

Kohei Yoshiyuki, Untitled, from the series The Park, 1971

Courtesy The Walther Collection and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

What may seem erotic and even offensive in the West is viewed quite differently in Japan. A naked body does not always suggest sexuality or eroticism. Sometimes it invites voyeurism. By pairing Nobuyoshi Araki and Daido Moriyama, two icons of Japanese photography, with the lesser-known Kohei Yoshiyuki, Acts of Intimacy: The Erotic Gaze in Japanese Photography, currently on view at The Walther Collection, invites New York audiences to contemplate personal and cultural definitions of intimacy and eroticism—subjective concepts that shift as the exhibition unfolds.

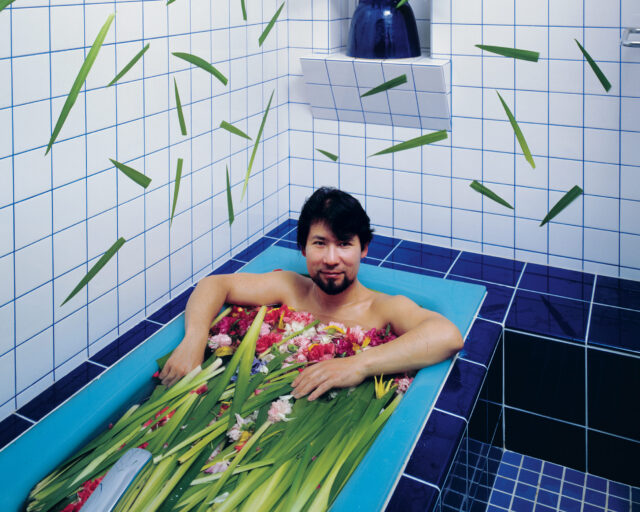

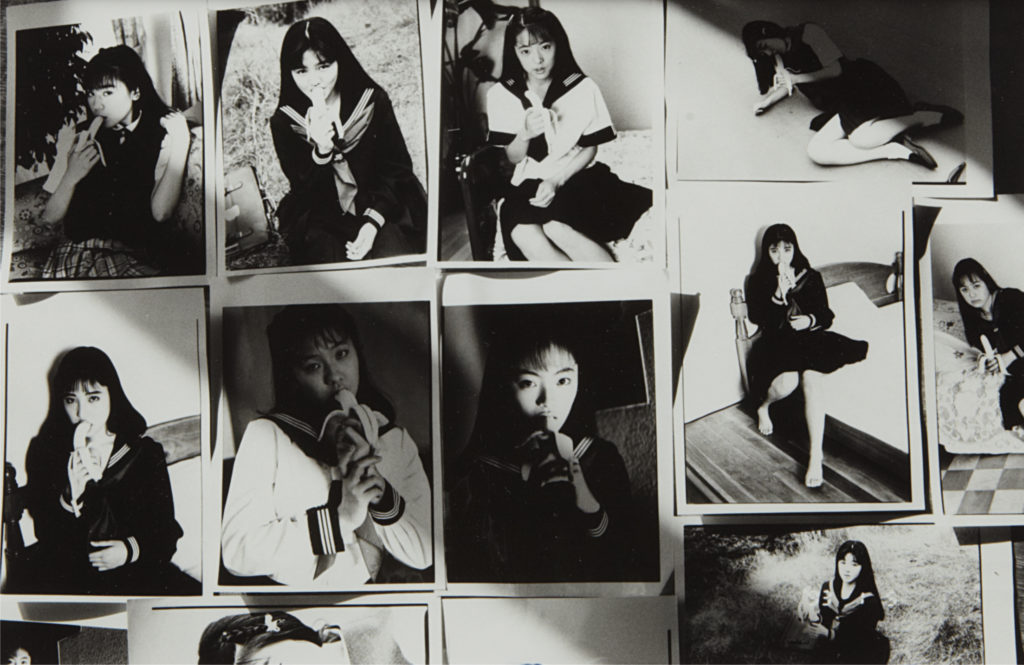

In the early 1990s, Nobuyoshi Araki gave the legendary photographer Robert Frank a handmade notebook of photographs during Frank’s visit to Japan. Later editioned as a series, 101 Works for Robert Frank (Private Diary) (1993) is the first work one encounters upon entering Acts of Intimacy. Presented in two closely gridded chronological rows that snake across the front section of the gallery and into a smaller side room, these intimately scaled prints—all date-stamped at the lower right corner—offer an encyclopedic view of Araki’s expansive visual vocabulary.

Courtesy The Walther Collection

Included are Araki’s typically notorious images of nudes, couples having sex, and provocatively bound women. But we also discover tender images of his cat, Chiro, the back terrace of his apartment, cityscapes, urban crowds, and cloud-filled skies. One of the last images is entirely black, except for the date stamp. Photographed from 1992 to 1993, using a snapshot aesthetic, these images mark Araki’s emergence from a long period of mourning following the death of his beloved wife, Yoko. There is eroticism here, often calculated to enhance Araki’s carefully crafted public persona as a photographer-provocateur, but the overriding perspective is the beguiling voyeurism of Araki’s private world made public.

Voyeurism creeps more aggressively into the show, and shifts our understanding of both Araki’s and Moriyama’s works, as Kohei Yoshiyuki’s series The Park (1971–79) comes into view. In comparison to Moriyama and Araki’s decade-spanning careers, Yoshiyuki’s fine art photography career is extremely short and based on this one series. Primarily a commercial photographer, Yoshiyuki stumbled upon the bizarre subject of hidden sexual encounters while out on late night walks in Tokyo parks. Armed with a 35mm camera, infrared film, and flash, Yoshiyuki’s images show straight and gay couples engaged in secretive sexual activities in the parks’ dimly lit areas.

Courtesy The Walther Collection and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

One wouldn’t think much of these grainy photographs, which were first published in the weekly tabloid Shukan Shincho, and decades later as a book, except that within view are groups of voyeurs who circle the couples. Yoshiyuki spent months befriending these spectator-participants, pretending to join them as they clandestinely observed the amorous trysts of unaware couples. The voyeurs’ extreme behavior, which often included attempts to touch the couples, reveal an aberrant underbelly that contrasts with polite Japanese social norms. What proves the lasting intrigue of these images—which some have suggested might be “yarase,” a Japanese journalistic practice of presenting elaborately staged images for the express purpose of selling magazines—are the layers of voyeurism and surveillance they suggest: The park voyeurs watch the couples, Yoshiyuki watches the voyeurs, and the gallery viewer watches all.

Courtesy The Walther Collection

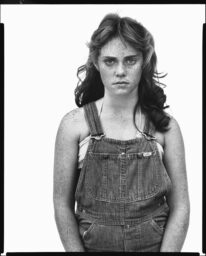

Moriyama, largely celebrated for his grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus urban aesthetic, is less often associated with eroticism. But for those who remember his Eros photographs, first published in 1969 in the seminal postwar Japanese photography journal Provoke, the sixty-seven images shot from the 1980s to the present in Moriyama’s series a room (2015) suggest a revisit to familiar territory. Filling the gallery’s back wall in a tight grid, a room, as with Eros, depicts nude women posed against rumpled sheets in the privacy of a bedroom space. Among the fragmentary views of exposed breasts, splayed legs, and skirts lifted to reveal various styles of women’s underwear, there are also images of overflowing ashtrays, stuffed animals, and ordinary household trappings. When viewed within the shadow of Yoshiyuki’s The Park, a room feels like peeking into a neighbor’s home from a window across an alley.

In his essay that accompanies the exhibition, curator Christopher Phillips points to Japan’s long history of publishing sexually explicit imagery. But the shifting of readings—from eroticism to both fetishistic and mundane voyeurism—gives Acts of Intimacy a more fluid and nuanced reading than the subtitle “the erotic gaze” suggests. Context is everything. The inclusion of Yoshiyuki acts to broaden our understanding of Moriyama and Araki, and reframes all three series within contemporary debates about pervasive surveillance, and the spectacle of private moments shared on public platforms.

Acts of Intimacy: The Erotic Gaze in Japanese Photography is on view at The Walther Collection, New York, through April 2, 2017.