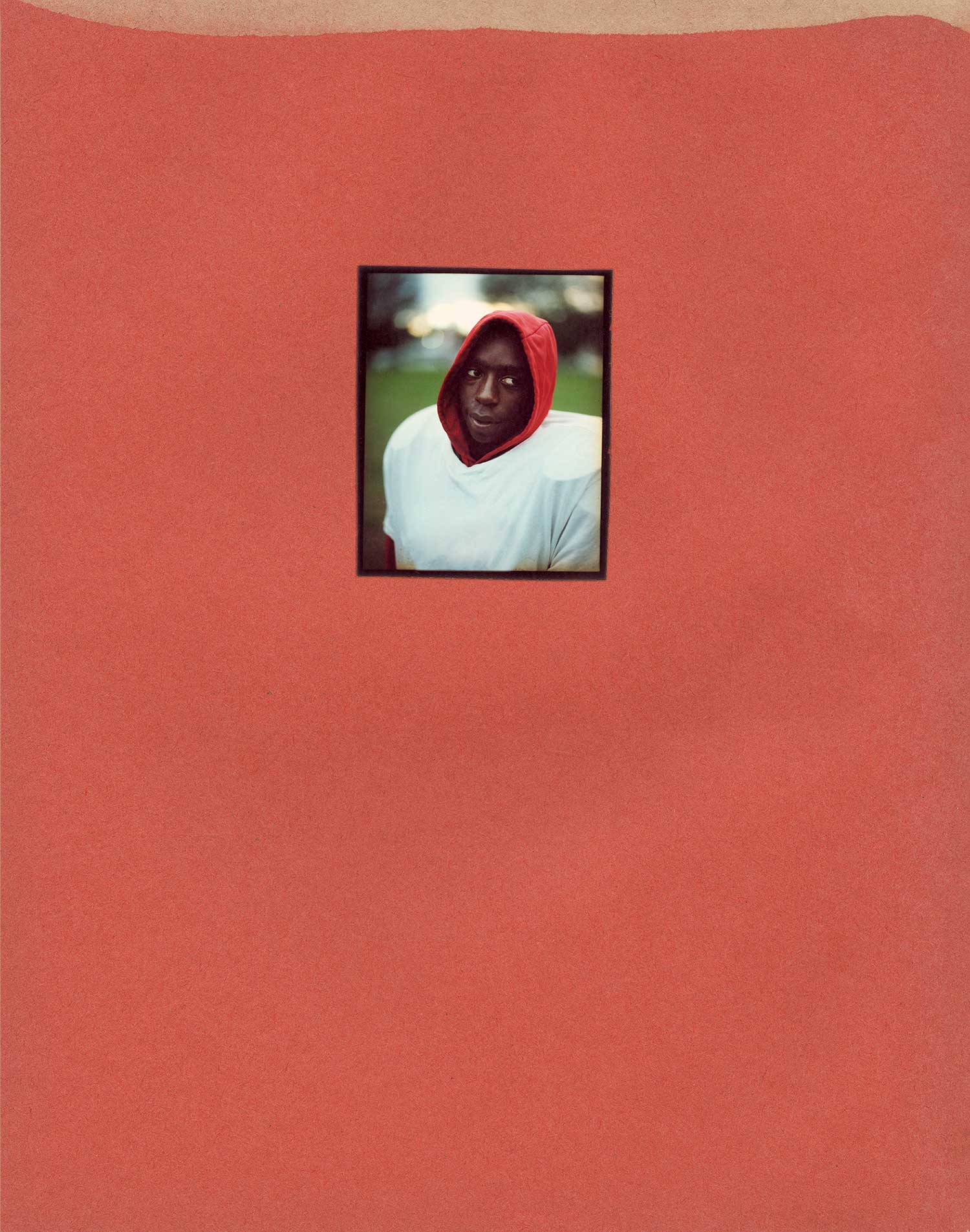

Gregory Halpern, detail from Omaha Sketchbook, 2019

Gregory Halpern exemplifies a new generation of documentary photography, less bound by the instrumental ends of activism and more determined to capture the conditions of American life through a lush, lyrical humanism that is simultaneously ominous and optimistic. In his newest volume of photographs, Omaha Sketchbook, published this month by MACK, Halpern offers an intuitive, nuanced portrait of the Midwestern city, mostly through shots of people and buildings captured elusively at dusk or bathed in honeyed golden-hour sunlight. Halpern’s purposeful meanderings through Omaha unspool as a rich meditation on the strangely threatening nature of American masculinity in all its expressions—or disfigurations. In fragile and unsettling images of male football players, prisoners, wrestlers, hunters, butchers, soldiers, and worshippers, Halpern seems to suggest that their hyperbolic posturing reflects the deep-seated anxiety around race and gender that fuels the country’s current political conflagrations.

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Brian Wallis: Your earlier photographs and photobooks—such as A (2011), East of the Sun, West of the Moon (2014), or ZZYXZ (2016)—have often used a kind of lyrical documentary approach to examine different regions of American culture. Your new book, Omaha Sketchbook, chronicles a fifteen-year engagement with one Midwestern city. What drew you to Omaha, what made you return, and what did you learn over that time?

Gregory Halpern: I wound up there by chance. I had just finished graduate school, had applied for a handful of residencies, and was given one by the Bemis Center in Omaha. I knew very little about Omaha, but I was feeling a bit aimless at that point in my life, and I was thrilled to go there. I wound up staying in Omaha after the residency was over—I took a job teaching photography at a community college there. Altogether, I was there for about half a year. Somewhere along the way, I started to feel like I had something to say, and a somewhat clear voice/vision was emerging.

Wallis: I was struck by the fact that the work in Omaha Sketchbook spans an extraordinary political arc, from the post-9/11 presidency of George W. Bush through Obama to Trump. Do you feel that your photographs record a change in the attitudes of Midwestern Americans?

Halpern: The period of time is crucial. I moved to Omaha in 2005, early on in the Iraq War. In 2003, then-President George W. Bush gave Saddam Hussein a forty-eight-hour ultimatum to leave Iraq, or else the US would invade. There was a picture on the cover of the New York Times the next day, a still from W’s speech. What struck me was that the still captured something in W’s face that spoke to his supreme (if wounded) confidence, while also capturing something fearful. It exemplified that connection that’s visible often in men between inadequacy and aggression. And weirdly, it was also an encapsulation of how when portraiture (or art in general) accepts contradiction into its form, it becomes all the more compelling. All of that is to say that I moved to Omaha with the Iraq War and that portrait on my mind, and with W’s sense of cowboy masculinity darkening my understanding of America. I returned to Omaha sporadically over the years, but I didn’t pick the project up and aggressively try to finish it until my daughters were born and Trump was elected. So, I suppose working on the sketchbook was a way for me to work through some of this over the course of fifteen years in a relatively private way.

Wallis: How did you go about collecting these images? At times, they seem casual or random, but you must have had a plan at other times to gain access to certain locations or institutions. Does your process require extensive research and planning?

Halpern: It’s a mix of random or casual moments, along with occasionally elaborate planning and research. Phone calls to get access. Stopping someone on the street or meeting someone online and making an appointment to photograph them, for example. I don’t have rules to the methodology.

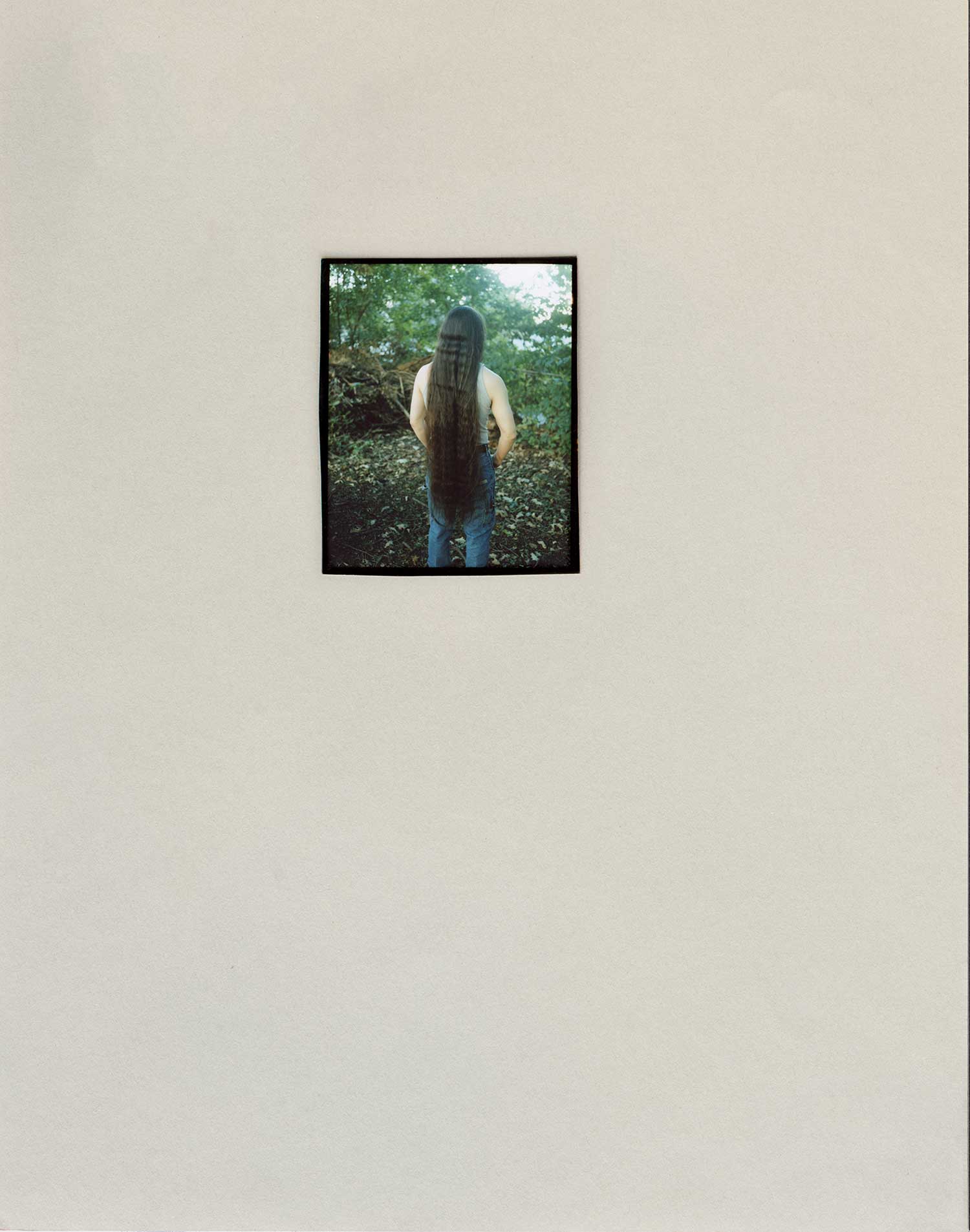

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Wallis: Your work recalls earlier photographic projects, from the road trips of Robert Frank and Stephen Shore to the reconfigured American landscape of the New Topographics photographers. At the same time, you allude to the loose narrative structure of the vernacular photo album, the casualness of certain independent films, and the happenstance observations of digital photography and Instagram. What visual models influenced your shaping of this project?

Halpern: I love all the work and genres you mention, but there aren’t honestly any specific “models” I could point to. I don’t think Instagram or digital photography influenced this work, though I started my sketchbook before those were part of my life. And I might add music to your list, because some of the pages, or the structure of the book itself, seem to be a visualization of certain musical forms for me.

Wallis: In your first book, Harvard Works Because We Do (2003), you used a very traditional social documentary approach—black-and-white photographs of workers, interviews and oral histories, statistical information—to support an activist campaign seeking higher wages for Harvard University service workers. That type of photography seems very different from the documentary approach you apply in Omaha Sketchbook. How would you characterize the differences in approach? And do you recall how you made that transition in your own work and why?

Halpern: The transition is because of my discomfort with the idea of speaking for, or on behalf of, the people pictured in Harvard Works Because We Do. I still believe in that project’s politics, but not in its artistic integrity. It’s useful as a tool of education or activism, but it’s too aggressively certain of itself to be a decent work of art. I no longer want to look at art that’s sure of itself and tells me how to think; I want work that respects the intelligence of its viewer, that’s driven by a sense of inquiry, curiosity, wonder, attraction, disgust, and an openness to contradiction.

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Wallis: Your approach in Omaha Sketchbook clearly relates to that of other contemporary photographers who use large-format color photography to document social conditions in the United States, but without direct reference to specific political issues or social conditions. Do you feel an affinity to or sense of collaboration with other photographers working in this vein? Do you see this as a new form of social documentary photography? And if so, what is the potential political impact on individual viewers?

Halpern: I don’t really see this as a new form of social documentary photography. I even hesitate whether or not the work is documentary. That term is a tough one for me. I’m not really sure what it means anymore. In a way, I think of everything I do as fiction, and yet I know that everything I do is also somehow rooted in reality or realism.

As for what the political impact of this work on viewers is, I really can’t say. I’m sort of cynical about the idea of photography having a profound political impact. Certain work breaks my heart. Judith Joy Ross, Milton Rogovin, Raymond Meeks, Mark Steinmetz. The work speaks to the fragility of life, the vulnerability of being human, and perhaps in that sense it’s political, or radical, in that it reminds us to be kind. But I’m skeptical of work that has an overtly political activist agenda. I sadly don’t think art is the best place to put your energy if you’re interested in social change. In a way, I’m wrong because, if you express yourself politically though art, you are presumably starting a conversation, and conversation is, in a way, the starting point for change. I’m just bothered by how isolated a bubble most of the art world exists within. Art is driven too often by capitalism, and exists too often within the circles of the uber-rich to have any teeth as a political tool. Photobooks and the internet are relatively free, but commercial galleries still drive so much of what happens within the art world, perhaps even more than museums, and to me, that’s a somewhat perverse kind of measuring stick for artists to be using on ourselves.

Wallis: One of the characteristics of a lot of this new documentary photography is a divorce of image from information, a deliberate ambiguity and a refusal of specific historical or political grounding. How do you account for this? And how do you think it relates to earlier forms of social documentary photography?

Halpern: I’m not sure, but I wonder if it’s part of a desire on photographers’ parts to distance themselves from that tradition, and from the idea of photojournalism. “Art photographers” often strive to be closer to painters, further from photojournalists. It’s funny, because there are so many great writers who move between the novel, poetry, essays, and journalism almost seamlessly, but maybe it’s harder sometimes, mentally, for photographers. But I think there’s the sense that some “social documentary” photography is naive, or pities its subjects, or creeps into didactic or sanctimonious territory. Not all, of course, and sometimes divorcing the images from the text or overt agenda would have done the work a service. I think perhaps audiences are just more visually literate now, because everyone is a photographer with their phones, and perhaps they need and want less direction from the photographer. The documentary aesthetic has profoundly compelling qualities, but in my mind, it’s strongest when a sense of realism is combined with a sense of wonder, or that exploratory, question-asking spirit of art-making, as opposed to a sense of lecturing or crusading.

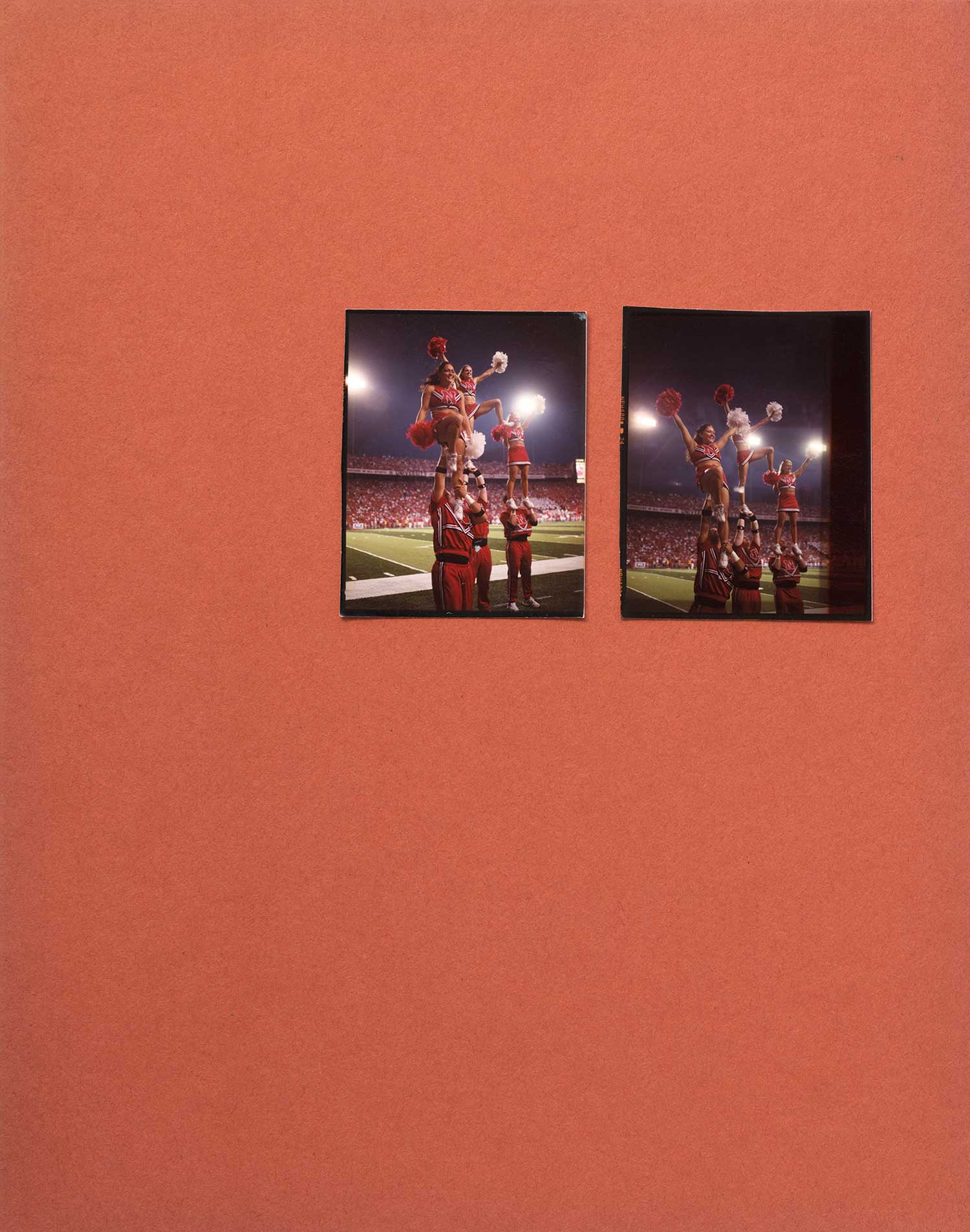

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Wallis: Many of your pictures in Omaha Sketchbook are of people, often portraits of workers, occasionally incarcerated folks, and sometimes individuals in some degree of distress. Did you seek out certain types or professions? Do you feel an ethical responsibility to the individuals you photograph?

Halpern: I think my responsibility to my subject is to make the most interesting and complicated portrait of them possible. To simplify or to caricature them would be to insult them.

Wallis: Certain ominous themes or issues are quite apparent in your sequencing of Omaha Sketchbook—the challenges of masculine identity, the threat of poverty and underemployment, the destruction and desolation of the Midwestern urban landscape—and yet your book seems to me quite hopeful. Does this assessment seem accurate to you?

Halpern: I love that you felt those two things about the work simultaneously. It does seem accurate, and it’s a sense that I think drives me, and almost all my work. Those are all

things I feel simultaneously about the world, and in a way, that’s what reality is—chaos and contradictions. I think to edit the world visually only for signs of hope, or only for, say, omens, would be a distortion and uninteresting to make or to look at.

Omaha Sketchbook was published by MACK in September 2019.