Minimal, Messy, or Melancholic?

The English word home does not have a Japanese equivalent but links to various terms and concepts: ie and katei relate to the house spatially; kazoku (composed of the characters for house and tribe) is the immediate family and household; furusato defines a nostalgic image of one’s home, hometown, or birthplace. Just as the Japanese language is highly situational, the idea of home also depends on the context. It is therefore not surprising that the motif of the home in Japanese photography is diverse, raising compelling questions: How do architectural photographs present the Japanese home? Are Daido Moriyama’s blurry 1970s images of the village of Tono linked to a hometown vision? What kind of family home do younger photographers portray in their work?

Courtesy Kochi Prefecture, Ishimoto Yasuhiro Photo Center and the collection of the Museum of Art, Kochi

Ie: Home as a house

Yoshio Watanabe, best known for his 1953 Ise shrine photographs, and Yasuhiro Ishimoto, who studied at the Institute of Design in Chicago before returning to Japan in 1953, were both concerned with the traditional architecture of Japanese temples, shrines, and villas. Unlike the Western idea of architecture that is durable and permanent, it has been a long custom in Japan to constantly change and re-create space, for example through the use of sliding doors and futon beds that are stored away during the day and taken out at night. In Watanabe’s Japanese architecture photographs and Ishimoto’s meticulously composed Katsura Imperial Villa series (1953–82), sliding paper doors and light tatami flooring contrast with dark wooden pillars; architectural shapes are captured as clear lines and geometric forms reminiscent of the Bauhaus (which in turn was partly inspired by a Japanese “purist” style). No detail is unplanned—forms and materials are in harmonious dialogue. The minimal, almost abstract photographic compositions convey a feeling of balance. The homes that Ishimoto and Watanabe present us with can be viewed as manifestations of the Japanese philosophy of space known as ma, literally “in-between.” The aesthetic of the rooms (and of the photographs) comes into existence through a careful interaction between form and non-form, dark and light. The transient concept of space can be seen as following the tradition of Shinto and Buddhist culture, emphasizing the impermanence of all things.

Courtesy the Third Gallery Aya, Osaka

Impermanence is also evident in a small city room in which paint is peeling off a sliding window frame. A pair of gloves, two umbrellas, and a kettle are attached to a laundry line strung across the room. It is the year 1978, and this home in Tokyo is one of manythat Ishiuchi Miyako captured with her handheld camera. The dark gelatin-silver prints show some apartments with and others without their inhabitants. They were published in Ishiuchi’s first photography book, Apartment (1978). In 1979, to her surprise, she received the renowned Kimura Ihei Award for this series. At the time, Japan was characterized by a fast-growing economy, which resulted in the area around Tokyo becoming increasingly urbanized. Residential buildings were erected rapidly and cheaply. Apartment documents people’s simple, provisional living conditions, often in temporary homes. The photographs cannot be separated from the photographer’s personal memories, as she lived in a similar apartment in Yokosuka on Tokyo Bay between the ages of six and nineteen. She has repeatedly told me how she hated growing up there. The apartments symbolize her own childhood home. “I wanted to return to all the places that I associated with bad memories,” she said. She has also described the apartments as being “permeated by a mix of different body smells. I have the feeling that the apartments smell thoroughly like people. These apartments are small, dark, and somewhat dirty, and nobody wants to live in them. But I sense a certain kind of reality in them—they are places that feel very human.” Her Apartment photographs are “human” primarily because they make visible the traces of their countless former inhabitants. Walls are covered in cracks, sweat stains, and fingerprints. Objects suggest stories about their owners. As in Ishiuchi’s later works depicting human bodies, clothes, or objects that people have left behind after their deaths, these poetic images tell of people, their mortality, and bittersweet remembrance.

Courtesy the artist

In 1993, the photojournalist Kyoichi Tsuzuki published a small-format book, Tokyo Style, that also documented small homes. Compared to Ishiuchi, however, Tsuzuki is less interested in the memories captured in rooms. Rather, his photographs of approximately one hundred apartments are concerned with everyday, real interiors. In one image, an electric guitar and large speakers contrast with traditional tatami flooring. Clothes are provisionally hung on a curtain rail. Using a large-format camera, Tsuzuki carefully constructs his photographs, presenting them with short descriptions about the rooms and their interior design or key furniture pieces, offering the same viewpoint on these inexpensive studio apartments as we might see on stylish apartments designed by famous architects. His now-iconic book was a reaction against the staged photographs of designer apartments found in interior design magazines and coffee-table books. When I spoke with Tsuzuki, he laughed about such fantasies and the “flowers that are usually not there, or fruit that nobody ever eats, and the interior designer who would also be at the photo shoot.” Such magazine photographs, and perhaps also the visual legacies of figures such as Ishimoto or Watanabe, have resulted in a stereotype of Japanese people living in Zen-inspired minimalist homes. “Although the great majority, around nine out of ten people in Tokyo live in tiny apartments, including members of staff that create beautiful architectural magazines, there was not a single book about their rooms,” Tsuzuki said.

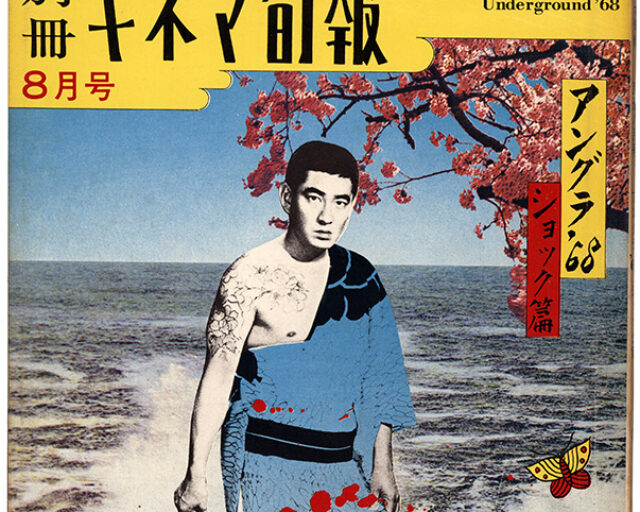

Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Furusato: Longing for home

In 1909, when the writer and ethnologist Kunio Yanagita visited the isolated village of Tono in northeastern Japan, it was mainly inhabited by peasants, and the first railroads were only starting to be constructed. Seeking to record the rural lifestyle and folk beliefs, Yanagita collected oral stories by the folklorist Kizen Sasaki The legends were published in a 1910 book titled Tono Monogatari (The Tales of Tono), revealing a dark world of the fantastic and reflecting a history of severe human existence. In the late 1960s and ’70s, a broad interest in Japanese folklore began to emerge, and Yanagita’s work was rediscovered. With the growth in prosperity, a concern with traditions found its way into people’s leisure life, as evident in the increasing number of cultural centers offering courses in all kinds of “authentic” Japanese arts. Within the contemporary challenges—enormous economic growth and internationalization on the one hand, student revolutions and protests against the 1960 Japan–United States Security Treaty on the other—nostalgic ideas of a “traditional” Japan ensured a familiar national and cultural identity. Moriyama’s photography book Tono Monogatari (1976) and Masatoshi Naito’s Tono Monogatari (published in 1983 but photographed between 1971 and 1982) reflect Japan’s folklore boom. Moriyama’s and Naito’s mostly black-and-white photographs of Tono, with their stark contrasts and dark imagery, convey a sense of the mysterious. Moriyama’s blurry, grainy images taken out of the train window on his journey to Tono or his cropped color photographs of flowers in someone’s garden, as well as Naito’s photographs of Tono at night, shot with a flash, suggest scenes that suddenly appear and then vanish again—just like indeterminate visual recollections unexpectedly surfacing from the dark realms of memory.

Courtesy the artist and Yumiko Chiba Associates

In Moriyama’s photobook descriptions of his journey, the term furusato plays a major role. The modern notion of furusato (literally “old village”) refers to one’s native place and is associated with nostalgic, warm feelings. Perhaps it is best described by the philosopher Ernst Bloch’s famous words about the home as a place that “shines into the childhood of all and in which no one has yet been.” There is a strong temporal component to furusato: it is linked with an image of the past, constituting a sentimental antithesis to the present. In the 1970s, Tono became regarded as an example of furusato: a warmly pastoral home that functioned as a romantic counterpoint to the prosperous, fast-paced, and Westernized Japan of the present. As the folklore scholar Hermann Bausinger once said, the expansion of the term home tends to coincide with the dissolution of one’s horizon. The loss of the war and the large-scale sociopolitical and economic changes since 1945 had surely dissolved Japan’s former horizon, resulting in a fundamental severance from home. It was this alienation from home that led to Japanese artists’ new concern with the idea. Moriyama writes about his wistful longing for Tono as an embodiment of furusato, which he defines as a “swollen utopia of countless childhood memory fragments.” Both Moriyama and Naito refer to the idea of the hometown as a “primordial image” in our subconscious, using a term coined by the psychoanalyst Carl Jung that defines images from the collective unconscious, shared among all humans. Moriyama confronts his hometown utopia by interacting with the real Tono through his camera. The medium of photography helps him to overcome, at least momentarily, his melancholic search for a home. When Moriyama leaves, he is able to say, “Tono, farewell for now.”

Courtesy the artist and Zen Foto Gallery, Tokyo

Kazoku: Home means family

Sometimes home is neither a particular place nor a distant memory. Funabashi Story, a series of images taken by Kazuo Kitai between 1983 and 1987, beautifully records people’s mundane lives inside apartment complexes in Funabashi, a city on the outskirts of Tokyo that grew rapidly in the 1980s. One of the protagonists is a child behind transparent curtains, curiously looking out a window while the television is on. The photographs have a narrative quality, and when Kitai published them as a photobook in 1989, he added texts that describe the homes and people’s domestic habits. “I decided to take photographs because I wanted to show people’s lives and hear their stories,” he told me, emphasizing that his viewpoint is not neutral but always aligns with the photographic subjects’ position. Kitai’s sincere respect for the residents is evident in his Funabashi Story photographs.

Yurie Nagashima, Takashi Homma, and, most recently, Motoyuki Daifu and Masaki Yamamoto have presented personal stories about their families. Nagashima first received attention in the male-dominated Japanese photography scene in 1993, as a young woman who portrayed herself and her family naked at home. They appear comfortably unclothed when posing for a family photograph or pursuing their daily routines. “I grew up in a free and open family environment, in quite a downtown style,” she said. “My family would walk around half naked with just a towel around their bodies after taking a bath. To me, nakedness is not necessarily something sexual.”

Courtesy the artist

In his photobook Tokyo and My Daughter (2006), Homma portrays the nonglamorous and domestic, interweaving photographs of his studio with a portrait of a small dog and photographs of a young girl who appears to be exposed to the loving eyes of her proud father. We see her grow from a toddler to an elementary-school child. In one photograph, she appears wearing the same shirt as Homma, who is checking the inside of a refrigerator in the back- ground. The girl stares directly into the camera, suggesting that she is aware of the viewer while also looking bored. The sequence of images conveys a diaristic feeling. With this book, Homma has shifted his attention from the formalistic suburban landscape to the closeness of the home space. The fact that the photographic story is fictional (the girl in the series is the photographer’s friend’s daughter) is not visible in the work: the book presents itself convincingly as a personal portrait of a father and a daughter’s life in the city.

Homma’s vision of a middle-class home contrasts with the cluttered, much more modest apartment in Kobe that Yamamoto has captured in a real and movingly intimate family portrait. Their tiny home, explored in his affectionate photobook GUTS (2017), is jam-packed with clothes, plates of food, cans, paper, and countless household objects. In between all this clutter, members of Yamamoto’s family are lying on the floor: sleeping close together, watching television, playing video games, and enjoying each other’s company. The young photographer seems to tell us that home is, above all, where one’s heart is—with one’s family and loved ones.

Read more from Aperture, issue 238, “House & Home,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.