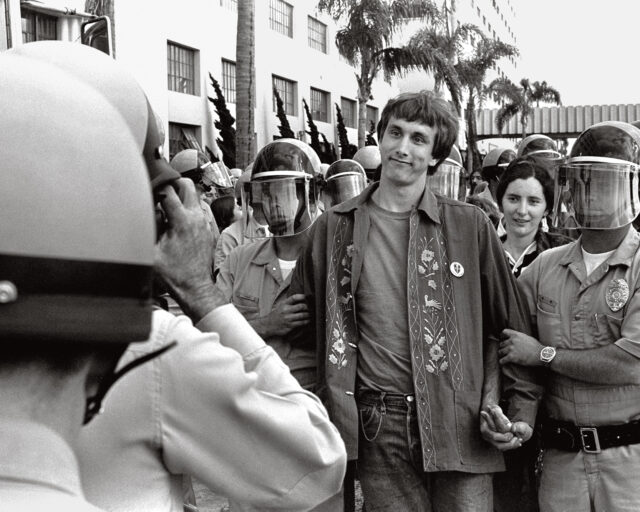

All That Glitters is Fool's Gold

From the gold rush to e-waste, Lisa Barnard’s new photobook offers a visual biography of a precious commodity.

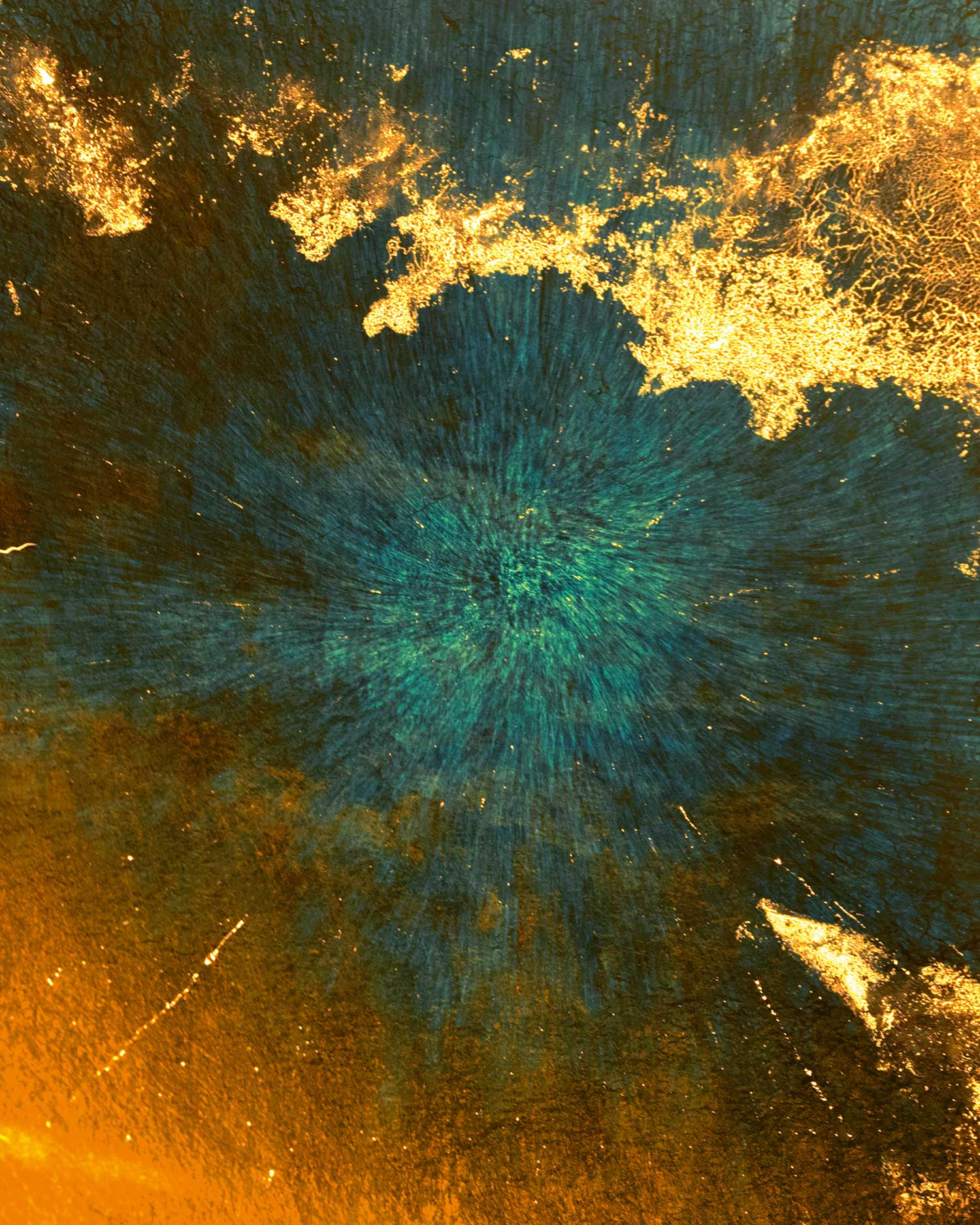

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Lisa Barnard’s new photobook, The Canary and The Hammer, is a whirlwind tour of humanity’s relationship to gold, from the Inca Empire to the California Gold Rush to present-day China, where the precious metal is both harvested out of toxic imported e-waste and studied in experimental medical circles. Through photographs, historical documents, and original texts, Barnard offers a non-linear, visual biography of gold and its exploitative, capitalist history. Of the book’s title, she writes, “Much like the canary taken into the coal mines in the twentieth century, gold is the gauge by which we monitor our economic stability. The hammer is the tool that smashes the structures in which it is embedded.” The project serves as the political artist’s response to the 2008 financial crisis, an exploration of our continued preoccupation with the accumulation of wealth.

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Elena Goukassian: Did you envision from the beginning that The Canary and The Hammer would span four years and as many continents? Did certain locations and narratives lead to an interest in other locations and narratives?

Lisa Barnard: I really wanted to make a project that reflected the fragmented society that we now inhabit. I was keen to look at how photography could represent visually not only what I was photographing, but also the structure of how I was putting the work together, which felt very chaotic. So, I always knew that the form of the project was going to be anti-formulaic and anti-series [compared to] how the art world works. I wanted to reference this idea of photography being this ubiquitous material, much like gold. (And gold, obviously, is everywhere; it’s very embedded within society.) I wanted to look at how gold as a material reflected our relationship to photography. It was about trying to organize and articulate the impossibility of articulating one truthful event through a traditional series of photography.

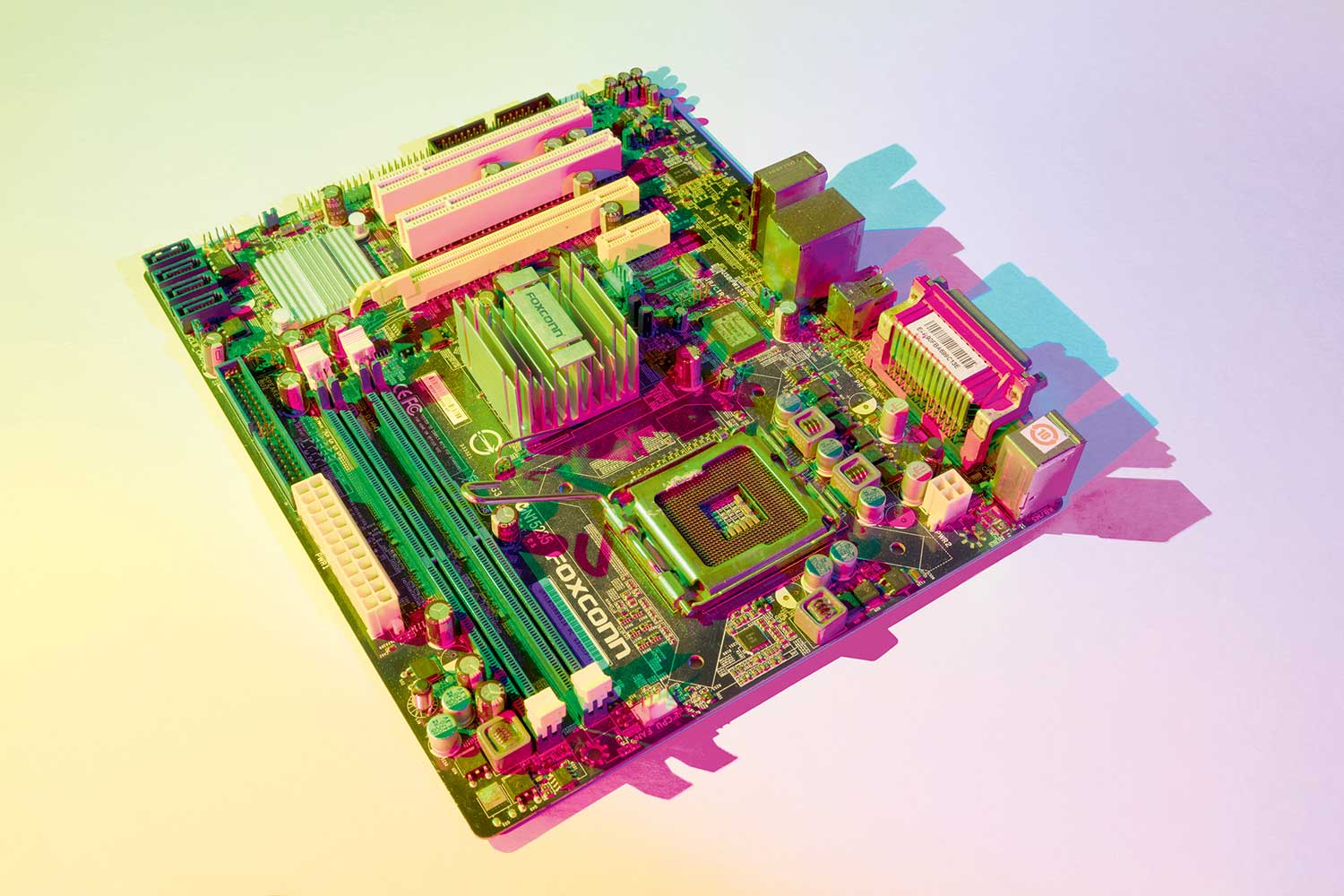

To make something that was very fragmented meant following multiple narratives around the world. While working in America, I didn’t realize that a third of the workers during the California Gold Rush came from China. Then I started to research China and discovered that China imported all of America’s e-waste at the time, in 2015. So, of course, then I wanted to go to China. Everything that I researched had a springboard effect of where I wanted to go next.

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Goukassian: How did you decide on the scope of the project?

Barnard: There were, and are, a number of places that I still want to go to. I’ve only touched the surface of this project. I wanted to get to a conclusion, because with this sort of work, if you sit on [a set of research] too long, it’s not valid any longer. You could end up updating the whole project all the time, because capitalism and the relationship between gold and finance move incredibly quickly.

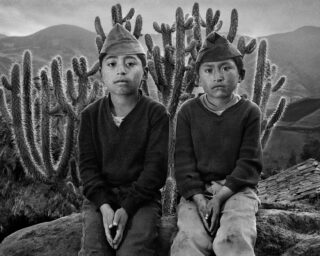

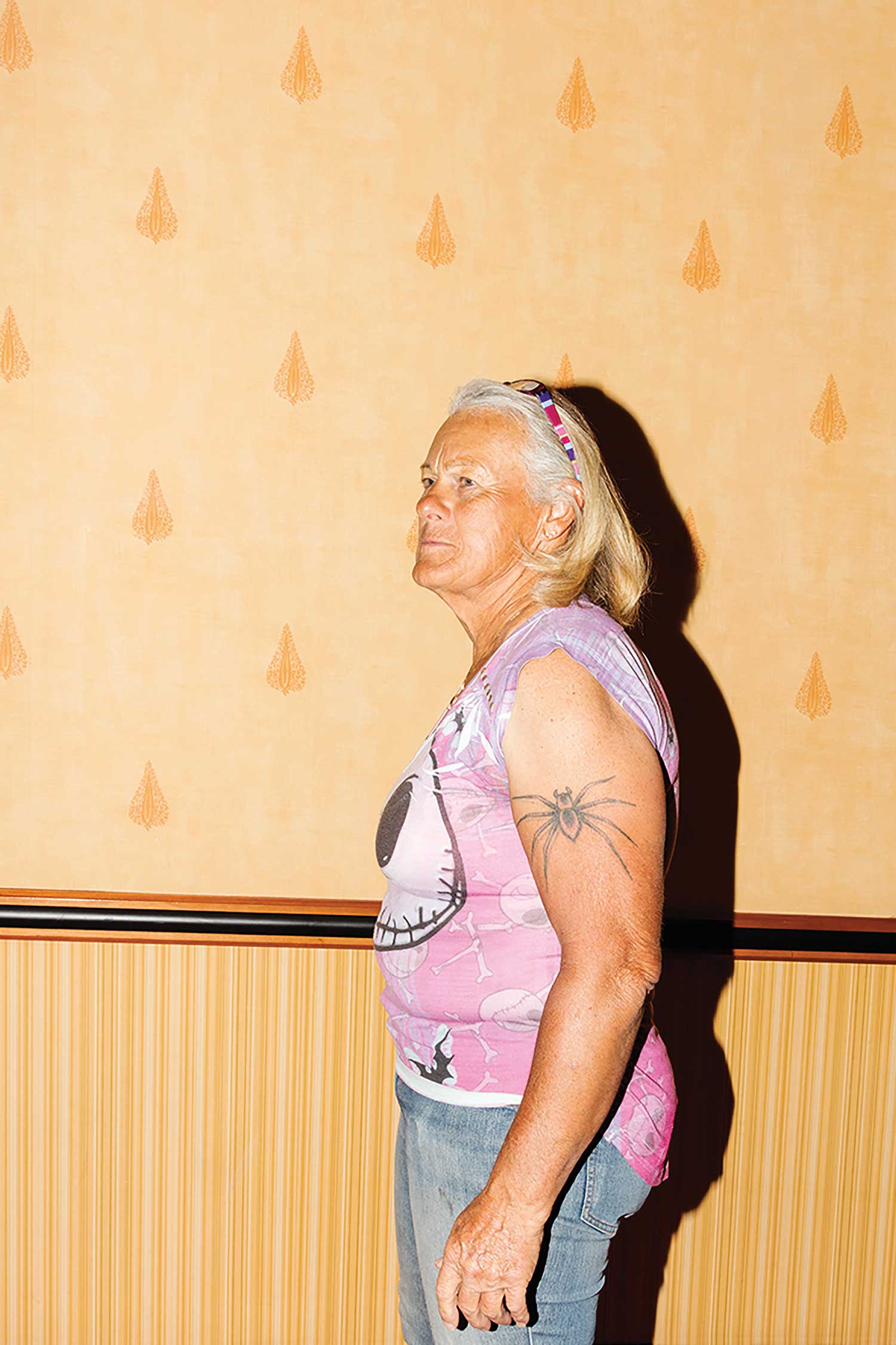

The project is about what I managed to make stick, as far as the access that I had and the people that I met. There were multiple narratives that I could’ve done in order to tell the same story in a different way. I’m really interested in who writes history and how history is written. Most of history comes from men, so an important narrative for me was this idea of the subjugation of women within the narrative.

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Goukassian: In a number of your works in the book, you use gold or fool’s gold in the art-making process—for example, the gold leaf on the back of the portraits of the pallequeras, female sorters of ore for gold pieces at the gold mine in Peru. How did you choose the specific pieces to focus on and how did you decide when to use real gold versus fool’s gold?

Barnard: The gold leaf was a way of trying to give value to the women in Peru. In Edward Curtis’s images of Native Americans, he used a process called orotone, where he put gold leaf on the back of glass plates. I wanted to reference that idea of the camera as a weapon of exploitation, and I wanted to counteract that by placing gold leaf on the back of these women that I spent time with in Peru, to try and give them value, as a way to tell people that I’m aware of the problems of being a European and going in and exploiting Native people for my own ends and for my own storytelling.

The fool’s gold I used on the 3-D renders of asteroids from NASA. I laid gold gesso and then did some screen prints on top of the asteroids. I suppose I wanted to use fool’s gold [to reflect] that the next capitalist expansion is going to happen in space—the plundering of asteroids—and how foolish that whole process will be. My fool’s gold was pointing to the ridiculousness of plundering one planet and then going off and looking for other places to plunder.

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Goukassian: You’ve noted that photography is a part of the capitalist narrative and often used as a tool to exploit. How do you reconcile this reality as a photographer?

Barnard: As a photographer, it’s very difficult for me to discuss using photography. This was an attempt to do it, but it becomes increasingly difficult. How do you justify getting on an airplane, spending a huge amount of money destroying the earth, in order to go and photograph Native people in their own country? How can you justify that? As a white European, I’m finding it increasingly problematic to come to terms with that, and my role within it. How do we justify making photographs as documentary photographers? There’s a very traditional, closed-off way that documentary photography is viewed, and I think it’s important to challenge that as much as possible.

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Goukassian: You seem to challenge this “traditional” view of documentary photography, at least in part, though your incorporation of historical photos and documents. How do you balance the use of archival materials with your own photography?

Barnard: I’m really interested in our relationship to archive. I do lectures on Derrida’s Archive Fever (2005), and I’m interested in the power play with archives. Artists tend to use archives quite randomly and irresponsibly—they dip in, use them, and create a new narrative that’s connected to their narrative that they want to talk about.

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Goukassian: They superimpose their own narrative on archival material.

Barnard: Exactly. And obviously, in relation to colonialism, that’s really problematic, because you’re rewriting. You need to be responsible. I’m interested in this idea of being a responsible photographer in relationship to archive. Archives for me are used purely as text, a way of underpinning a particular idea that I want to discuss. I’m not using them in a way that’s different from their original use. For instance, with Operation Fish, [when, in 1939, the UK evacuated gold bars to a clandestine location in Canada, hiding the nation’s wealth from the advancing Nazis], this was a particular narrative that I knew nothing about. I got in touch with Rodney Agar, and he was really happy for me to use the archive at the Imperial War Museum in London. I was keen to make sure that I used it responsibly, because these were personal photographs that were taken by his uncle [Augustus Agar, an officer in the Royal Navy]. Archives, for me, have a very specific means to an end; I’m not trying to reinvent anything.

Lisa Barnard, from The Canary and The Hammer, 2019

Courtesy the artist and MACK

Goukassian: Do you think that gold will ever lose its power over humanity?

Barnard: No, I don’t. Because of gold’s ubiquitous use within the medical and science fields, and within mobile phones and screens and TVs and everything, I think there’s always going to be a need for it; there’s always going to be a desire for gold that is going to outweigh anything else. And there’s only a finite amount on earth. But it depends if we can plunder asteroids, because if the market becomes saturated with gold, it will potentially lose its value. So, who knows what will happen in the future.

Lisa Barnard’s The Canary and The Hammer was published by MACK in September 2019. Excerpts from the book and additional stories of humanity’s relationship to gold are available on the project’s website, The Gold Depository.