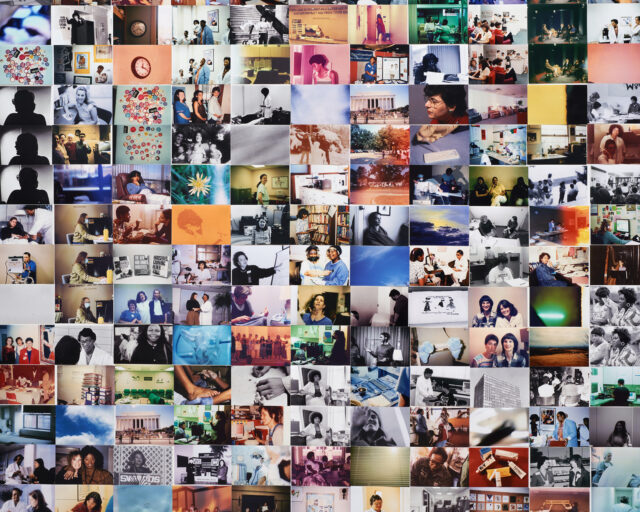

Martine Syms: Conscious Resistance

In photographs and videos, an artist pushes back against reductive stereotypes of black life.

Martine Syms, Stills from Notes on Gesture, 2015. Single channel video, 10:27 minutes (loop), color, sound

© the artist and courtesy Dominica Publishing and Bridget Donahue, New York

Another week, another video depicting the execution of a black man at the hands of a police officer goes viral. Another black man rendered absent: Walter Scott, Eric Garner, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile … when do I stop? And what of the black women who are prematurely disappeared? It is with this horrific backdrop of continued abuse of power—which has resulted in 559 deaths at the hands of U.S. law enforcement in 2016 alone (as of July 8, 2016), only a fraction of which have actually been visualized—that I can begin to talk about the positive power of Martine Syms’s art, feminism, and photographic presentation of black women, black life, black power.

Syms’s work, foremost, is a conflation of image and text—both are primary to her practice. For a number of years Syms was the director of Golden Age, a Chicago-based project space focused on printed matter. She later founded Dominica Publishing, an imprint for artists that continues today. This fundamental relationship to and engagement with language connects all of her endeavors. As with her writing, Syms’s development of a visual aesthetic references the structures of cinema and television. The artist states that she is creating a relationship between image and text in order to produce a resultant “third meaning.” Now based in Los Angeles, Syms is closer to the Hollywood apparatus; this proximity is evidenced in her art, almost having become a character itself. But the most constant character of all is that of a black, female protagonist.

Martine Syms, Fact & Trouble, installation at Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 2016

© the artist and courtesy Dominica Publishing and Bridget Donahue, New York

Vertical Elevated Oblique (2015), Syms’s first solo exhibition in New York, at Bridget Donahue, offered an overtly technical installation comprising video, photographs, and staged objects, as well as a space for books from Dominica Publishing. For Notes on Gesture (2015), the featured video, Syms employed a female, black actor to enact gestures readily associated with black women and blackness. Interspersed with shocks of text (“DON’T JUDGE”; “WHEN IT AIN’T ABOUT THE MONEY”), Notes on Gesture is an exercise in nonverbal expression. The video essentializes the essentializing: black women as sassy, finger-snapping, mm-hmming folks. Gestures of blackness are often co-opted, but here we do not know which gesture is authentic or which acts as a quotation. Syms presents an intentional flatness to the image that supports the myth and refutes the dimensionality of its subject. But is this body and identity really just an empty vessel of expression?

The installation of Vertical Elevated Oblique smartly collapsed language and image, layering pop culture with enduring symbols of both Hollywood (industrial stands used in film production now held up Syms’s photographs) and the black resistance (a flock-covered black panther, originally intended as a support for a glass tabletop, co-opted from the Black Panther movement by the home and now repurposed by Syms).

Martine Syms, Stills from She Mad: Laughing Gas, 2016. Four-channel video installation, 6:59 minutes (loop), color, sound

© the artist and courtesy Dominica Publishing and Bridget Donahue, New York

Syms’s photography-based work is a conscious resistance that rejects what we see in the media— a construction of what is real— and flips the balance simply by the fact that it is Syms behind the camera, creating her images. If images of black people are going to continue to be fed into an endless and cruel cycle of stereotype, we may as well control the output—present them as mundane and normal, insert them into history, and reassert them in the contemporary. Syms’s video She Mad: Laughing Gas (2016), modeled on a silent film, Laughing Gas, from 1907, does exactly that. We follow Syms-as-protagonist to the dentist, where she engages with the hygienist, gets high on the titular gas, and is ultimately denied coverage for the visit by her insufficient health insurance. A distinctly American experience.

The power of what Syms does is not only in its visual strength, but also in its political implications in an art world marked by a dearth of diversity in proprietors and artists alike, and in a media universe that suppresses (whether consciously or not at this point) positive images of black life. Syms, by simply representing “herself”—and specifically black women—in the context of institutional, commercial, and codified spaces, is asserting her presence. And that, by nature, is feminist and political.

Read more from Aperture Issue 225, “On Feminism,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.