Father Figure

Masahisa Fukase, From the upper left: model A, Toshiteru, Sukezo, Masahisa. From the middle left: Akiko, Mitsue, Hisashi Daikouji. From the bottom left: Manabu, Kyoko, Kanako, and a photo of Miyako, 1985, from the series Family, 1971–89

© Masahisa Fukase Archives and courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, and Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

The Japanese photographer Masahisa Fukase is best known for his celebrated photobook Ravens (1986), a work in which he projected his sense of isolation and sadness, arising from his 1976 divorce, onto the figures of ravens. More than thirty years have passed since the publication of Ravens, and it is still lauded as one of the most monumental achievements of Japanese photography. But in 1992, Fukase suffered a traumatic brain injury that brought an end to all of his creative endeavors; it also resulted in the greater part of his photographic works, excepting Ravens, falling into oblivion for the next twenty-five years. Considerable scope remains for reassessing what Fukase was trying to accomplish in the course of his forty-year-long career as a photographer. Two works made over long stretches of his life, Family (1971–89) and Memories of Father (1971–87), are essential for any understanding of his photographic art.

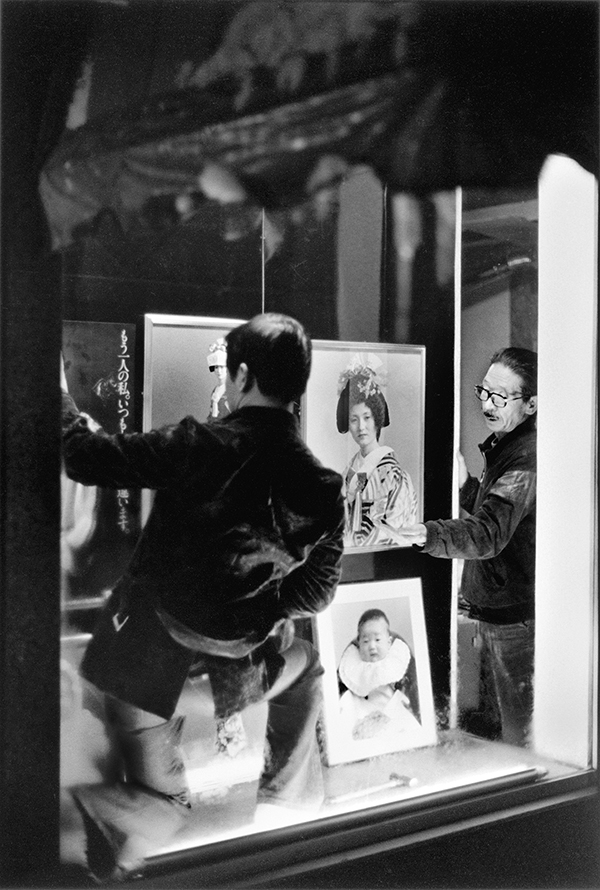

Masahisa Fukase, Untitled, from the series Memories of Father, 1971–87

© Masahisa Fukase Archives and courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, and Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

Fukase, who died in 2012, left a large and varied body of work, both personal and ludic. He was born in the small town of Bifuka, in the Nakagawa district of Hokkaido, the eldest son of a family that ran a provincial photography studio, which had been in operation since his grandfather’s time. His father, Sukezo, had hoped that Fukase would take over the family business, and made his son help with the processing of prints from the tender age of six. In one recollection, Fukase notes that “the grudge” he harbored toward photography had its beginnings around this time, suggesting an ambivalence about his first encounter with photography and the way his life seemed to have been decided for him. In 1952, at age eighteen, Fukase left home in order to get formal training, entering the photography department of the College of Art at Nihon University, in Tokyo. After graduation, he stayed on in Tokyo and took a job as a commercial photographer—not, in the end, going back to run the family business. While working at this position, Fukase threw himself into improving his photographic expression, and gradually started making a name as a conceptual photographer, getting his works published in magazines like Camera Mainichi and Asahi Camera.

In 1964, he married Yoko Wanibe. The autobiographical photographs he took of his domestic life with her have often been compared to Japanese I novels, with their self-revealing, confessional tone; his images were, in fact, the cause of continual friction between husband and wife. Wanibe stated, in 1973, that “in the ten years we lived together, he really only looked at me through the lens of the camera, and the photographs that he took of me were unmistakably depictions of himself.” As Fukase himself noted: “In the end, a kind of paradoxical situation came about in which we seemed to be together only for the sake of my photographs. This by no means made for marital bliss.”

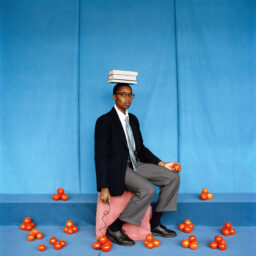

Masahisa Fukase, Untitled, from the series Family, 1971–89

© Masahisa Fukase Archives and courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, and Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

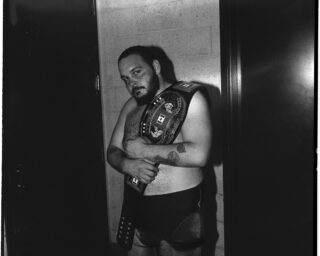

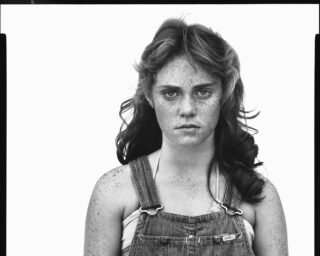

In 1971, suffering considerable existential torment, Fukase began making periodic journeys back home to Hokkaido, after a long absence. In the locale of his native village—the very starting point for his whole being—Fukase started to explore the source of the creative energy that poured endlessly out of him, the compulsion to obsessively take photographs of the people he loved—even to the point of hurting them. The photographs he made over this roughly twenty-year period include the ones seen in Family and Memories of Father, both published in book form in 1991. Family is essentially an album of commemorative family portraits, all taken inside the family’s studio on anniversaries. Memories of Father is a collection of photographs, taken over a decade and a half, of his father, following Sukezo’s life and death through to cremation, interspersed with shots of the family’s daily life.

Masahisa Fukase, Untitled, from the series Memories of Father, 1971–87

© Masahisa Fukase Archives and courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, and Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

Having in the 1960s turned his personal life with his wife into art, Fukase now took up the most ordinary, mundane, and everyday format: the family album. Yet in Family, he includes a number of nude and seminude women, photographed in the 1970s, who have nothing whatsoever to do with his family. He seems to be inviting the viewer to enjoy a kind of joke—at the same time perhaps performing a type of self-parody, underlining how he is the failed, degenerate, third-generation son. In 1985, after a blank of ten years or so, once again his father appears in the photographs, by now markedly older. Fukase understood, as he himself wrote, that “every member of the family whose inverted image I capture on the film inside my camera will die. The camera catches them, and in that instant it is a recording instrument of death.” He elaborated on this idea: “Time passes inexorably, and death comes to us all. It comes to old people, to young people, to children, to me. For me, everything is a commemorative photograph, to be eventually stuck in a battered old photo-album.”

For Fukase, a photograph was not something to record the successful moments of a life fully lived: rather, it was to record the time spent until the unavoidable day of death eventually provides a fitting end point. Fukase was surely well aware from early on that Memories of Father would be brought to a final full stop by Sukezo’s death. He saw photography as a macabre art, one that allows the viewer to exist, in some sense, unbound by the progression of time.

Masahisa Fukase, From the upper left: Masahisa, Toshiteru, a photo of Suzeko, Takuya. From the middle left: Akiko, Mitsue, and Hisashi Daikouji. From the bottom left: Manabu, Kyoko, Kanako, and a photo of Miyako, 1987, from the series Family, 1971–89

© Masahisa Fukase Archives and courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, and Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

In 1987, Sukezo died, after having succumbed to pneumonia. On the night before the funeral, a heavy snowstorm covered the town of Bifuka in snow. Fukase gathered the whole family together, some dressed in their mourning clothes, and once again took a commemorative photograph. In the position his father used to occupy, he placed a photographic portrait of Sukezo, which Fukase had taken in 1974. The person in the photograph has a restrained smile, even though the occasion is now his own funeral. The suggestion seems to be that commemorative photographs have to be taken of all family events, and all commemorative photographs have to be marked by beaming smiles. Even though Sukezo himself is deceased, he has been brought back to life by that instrument of death, the camera. Now he is being photographed again—allowing him to stare out at the viewer, even though he exists only within a photograph—death canceling out death.

Two years later, in 1989, Fukase’s brother divorced, and the brother’s wife and their two children moved to Tokyo. Fukase’s younger sister and her husband moved away to Sapporo. His mother took up residence in a nursing home for the elderly. What had begun in 1971 as a lighthearted parody of a family photo-album had gradually changed over the course of twenty years and met an entirely unexpected end: the family itself scattered to the winds, their photographic studio closed—the end of an era that had lasted eighty years.

Masahisa Fukase, from the series Family, 1971–89

© Masahisa Fukase Archives and courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, and Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

In these works, Fukase uses the camera as a kind of pistol, puncturing the boundaries of time. The bullet moves at an extremely slow speed, seemingly almost motionless, eventually reaching its desired target. The dead body that lies on the ground is the corpse of the past. Fukase pulled the metaphorical trigger over and over again, first on his wife, then on his family. His shots pass through them all over a period of several decades. In effect, what we look at when we view Fukase’s photography is a heap of the remains of the past, a grave marker composed of layers upon layers of images. The viewer gets an intimate sense of the disintegration of Fukase’s father, of the photography studio, and of the entire family, but also becomes conscious of the strange, rather macabre ease with which the photographer invites us to go back and forth through time with these photographs, the only thing left to us now that he—the practitioner of this art—is also dead. In the same way that the reappearance of Sukezo in a photograph of his own funeral seems to negate the effect of death, the members of Fukase’s family actual corpses of the past—come to life in these photographs and stare unflinchingly straight out at us.

Masahisa Fukase, From the left: Hisashi Daikouji, Kanako and Miyako, Manabu, Mitsue, Sukezo, Kyoko, Akiko, Takuya, and Toshiteru, 1974, from the series Family, 1971–89

© Masahisa Fukase Archives and courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, and Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris

Read more from Aperture, issue 233, “Family,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.