Queer Looking, Queer Being

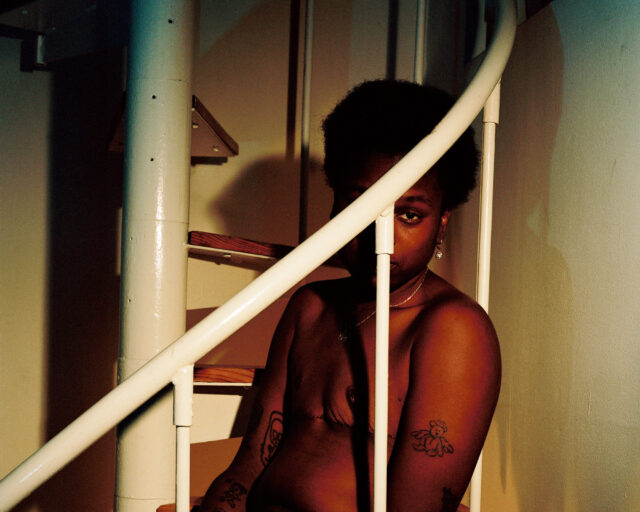

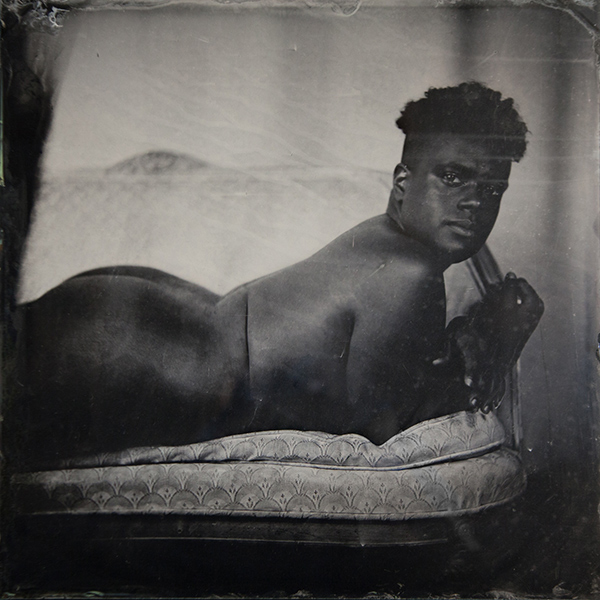

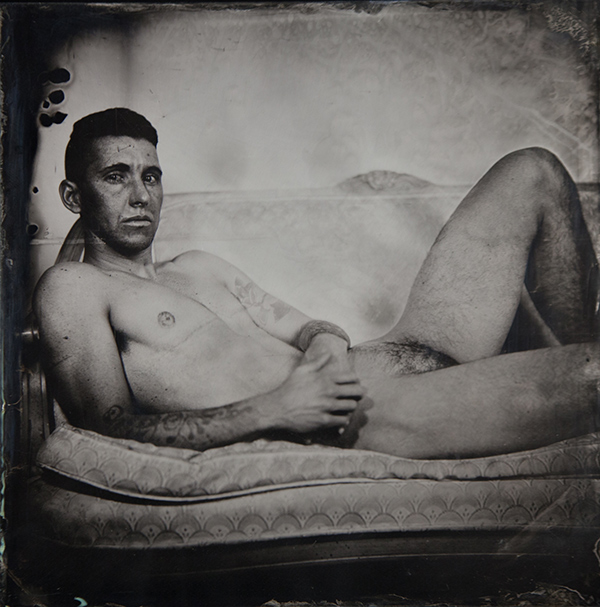

Rowan Renee, Untitled, 2015, from the series Z

Courtesy the artist

This conversation is excerpted from a much longer dialogue between artist Rowan Renee and critical viewer Arno Mokros. Our conversation has spanned over two years, fifty written pages, and many hours of recorded audio. We first met in 2015, during an open studio at Pioneer Works, where Rowan presented work as an artist in residence. The photographs on view were from Z, a series of nude ambrotypes dealing with gender ambiguity across a spectrum of trans, cis and gender-nonconforming identities. Arno’s first encounter with Renee’s photographic work at Pioneer Works sparked an initial conversation, which then expanded into an ongoing dialogue.

Rowan Renee: Do you have an image that stands out in your mind? When I met you during the open studio, I remember watching you look at the images and thinking that I could tell that they were making an impact on you. I wonder if there was an image you saw on that visit that particularly struck you?

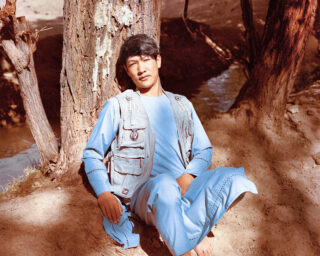

Rowan Renee, Untitled, 2015, from the series Z

Courtesy the artist

Arno Mokros: I think the image pictured above was in your studio the first time I was there. If you’re someone who’s familiar with the trans community, there’s a series of symbols or signifiers attached to trans male bodies that are very recognizable. One of them is chest scars, top surgery scars. They are so visible in this image. I have an immediate recognition of that signifier because of my own trans identity and internalization of what trans men look like. Actually, I consider that to be part of the process of initiation to being trans: learning what it means to live a trans experience on a bodily level. That aspect of initiation has involved me studying what the body is “supposed” to look like as a trans man.

Renee: What do you mean when you say what a trans man is supposed to look like? Are you talking about assimilating to conventional representations of masculinity?

Mokros: What trans men look like as a type. What an attractive trans man looks like. What is acceptable for that body. I read this model’s body as masculine for particular reasons, in response to certain signifiers, which all operate to facilitate “passing” as one gender or another. I think there’s a distinction between recognizing a body as masculine-of-center, as opposed to discerning “maleness” and “femaleness” in terms of sex. This image puts on display the intersection of masculinity and female-embodiedness. Something I always say is that “I’m a queer-bodied person.” And that’s because queerness is always visible on my body if it is exposed. So I see a specifically queer body in this image, a representation of an expression of trans masculinity, in both an embodied and performative sense. As a viewer, I don’t actually know this person’s identity, but the judgments and determinations through my own perception are inseparable from my queer subjectivity. I acknowledge that I project a lot of myself onto that image, onto what I’m arguing that this image puts forth. In part, my insecurities about maleness/masculinity, femaleness/femininity, bodies, sex, and gender are on display through my own reading of this image.

Renee: The queer embodiment in this image is legible to you as a trans man.

Mokros: Yes, but I know the signifiers. Like being able to recognize chest scars as part of the trans body—that’s legible to me.

Rowan Renee, Untitled, 2015, from the series Z

Courtesy the artist

Renee: In the experience of talking to different people who have seen this image, there are a lot of people who don’t know the signifiers, and read it in a very confused way. In the “trapped in the wrong body” narrative that is so widespread in the mainstream understanding of trans identities, I think there’s an underlying feeling that there is a contradiction present if the genitals don’t match what is assumed to be biologically essential to gender. Like that all men have penises.

Mokros: Really? I can’t even fathom that level of unfamiliarity anymore, but that just shows how invisible trans bodies are, really. The first time I saw this in your studio I didn’t have a context for your work and I didn’t have any assumptions about the content of your work, or who your work would represent. So I walked in and I was honestly quite pleasantly surprised to see bodies like mine. In my own life, I seek out images of trans bodies for a variety of reasons, but they’re usually not presented to me spontaneously. Seeing your work was a moment of realizing someone else was on the same wavelength. I don’t mean that I felt a connection to this person because he is also trans, but rather that I could recognize that you considered some of the same questions that I did in the process of documenting, in considering other trans bodies. It introduced me to an immediate sense of trust with you. Probably if I hadn’t seen this image I wouldn’t have talked to you at all. As much as I would have liked your work anyway, it would have been really different. I might not have been as curious.

Renee: Am I projecting if I say that you connect to this image because you are able to empathize with the sitter, and that you recognize in him a vulnerable visibility of the body that you relate to?

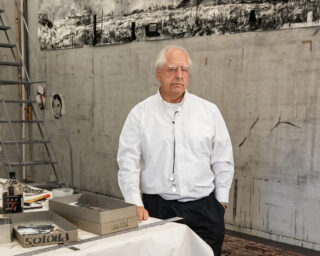

Rowan Renee, Untitled, 2015, from the series Z

Courtesy the artist

Mokros: I think it evokes the potential, the possibility (and maybe even the risk) that my own body will be made visible. I think about how other people read me every day. It is part of my routine to be sure I pass as male whenever possible. I avoid situations in which I am forced to explain my gender history. I don’t often—or really ever—present my body to other people on its own terms. I don’t know what it feels like to have everything on display. I think some people are confused by the bodies in these photographs or trans bodies in general because they are simply ignorant of the diversity of bodies in this world. I spend time wondering: twenty years from now, will the general population recognize that trans bodies are not anomalous, but rather just some of many possible forms? Will we be at a place when people no longer assume bodies are either male or female? Personally, I don’t know what it would feel like to occupy space in my body on its own terms, to not try to be seen as a cisgender male to the outside world. But this image is visible to the outside world now, and it isn’t about being seen as a cisgender male.

Renee: It’s about showing that you’re not.

Mokros: So often, and I would say too often, images of trans people have been about—especially in erotic or porn settings—gender expression as a trick. As if a person’s genitalia reveals that you’ve been fooled and “this is really a man” or “really a woman.” I was attracted to your work because I felt that you were doing something more than “documenting” trans and gender-nonconforming bodies as curiosities to be fetishized or as human interest pieces. The models in this body of work are vulnerable as nude subjects before the camera, and yet I feel they are safe within your frame, and that you resist and protect your models from being fetishized and misunderstood because of how you capture them. When I came in contact with your work, I felt that you were contributing to the representation of queer and trans bodies, but also thinking beyond representation—perhaps even navigating your own relationship to gender. It’s often assumed that trans people are subjects, while photographers occupy an objective, masculinist, cisgender perspective. As an artist, I think you make clear that you are a part of the community you photograph, and that you are immersed in the same questions about queer identification, representation, and self-determination.

Renee: Yes, I think you’re touching on the myth of objectivity in documentary work. I wasn’t following a proper documentary photographic practice. I didn’t see myself as an outside observer while making Z, but I also didn’t yet see how I fit into the conversation. I was searching for a language and a community that gave form to feelings that otherwise seemed illegitimate in a heteronormative (and homonormative) society. I was learning how to be queer. I worry that it sounds narcissistic to shift the focus of a portraiture project to my own inner landscape, but I also think the motivations of the photographer are relevant and inevitably affect the work. I’ve been thinking a lot about how queer knowledge is transmitted through dynamics of interpersonal relationships between queer people. How a queer education often plays out in relationships rather than within institutions.

Rowan Renee, Untitled, 2015, from the series Z

Courtesy the artist

Mokros: I actually think your work creates a queer space, and it sounds like you’re saying that the photographic process itself was a creation of queer space in which queer knowledge passed between you and the models you worked with.

Renee: Yes! That’s it. Part of the process of making Z was to fight against power dynamics of model-photographer relationships. But, I don’t want to sound overly naive about power or my role as a photographer. There’s a reason why queer spaces often radically challenge systemic power structures, and part of that is an underlying recognition of how power does not necessarily have to be wielded as an absolute. I thought of my role as a photographer as a constant negotiation of the terms and boundaries of the artist-model relationship, which implies that consent isn’t fixed or absolute. It’s in flux and always on the table for renegotiation. There were aspects of my process that were about surrendering control, both in how I worked with people and the technical limitations of the wet-plate collodion process. For me, this helped me understand why I seek out queer images: to access queer possibilities for being in the world. It is especially important as a genderqueer person, because this is still a contested area without legal recognition in most places.

Mokros: It seems to me that, in your practice, seeking out queer images also involves producing queer images. They are disseminated to all your viewers, but might especially resonate with a viewer like me, or other queer, trans, and gender-nonconforming folks. You’re queering our sense of possibility.