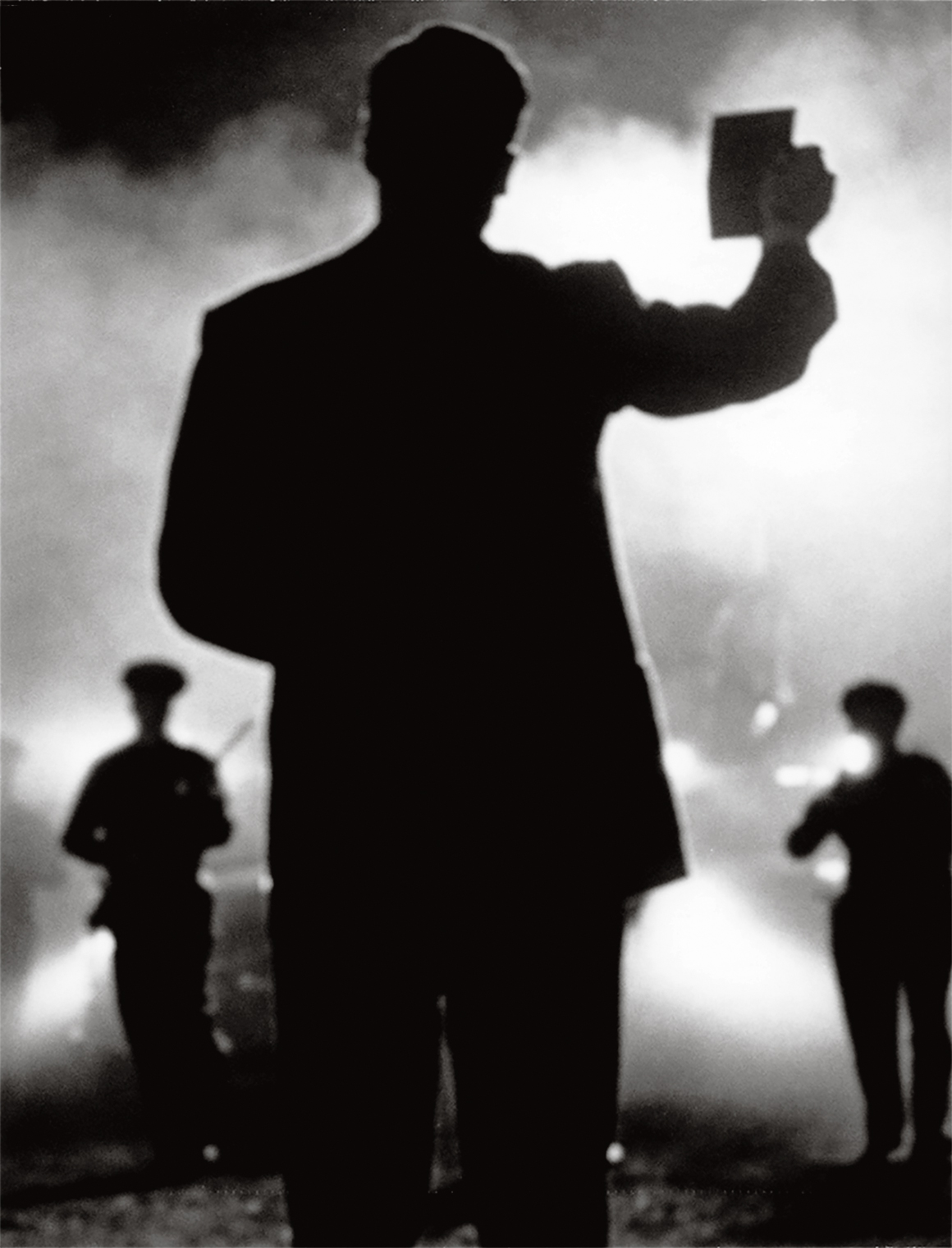

Ryan Spencer, Untitled, 2016

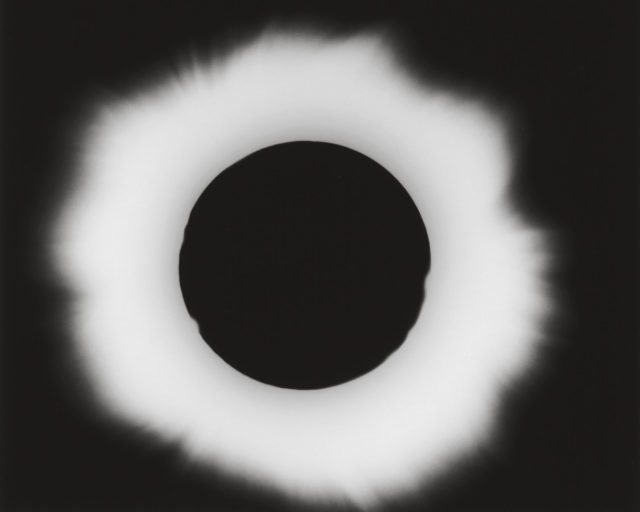

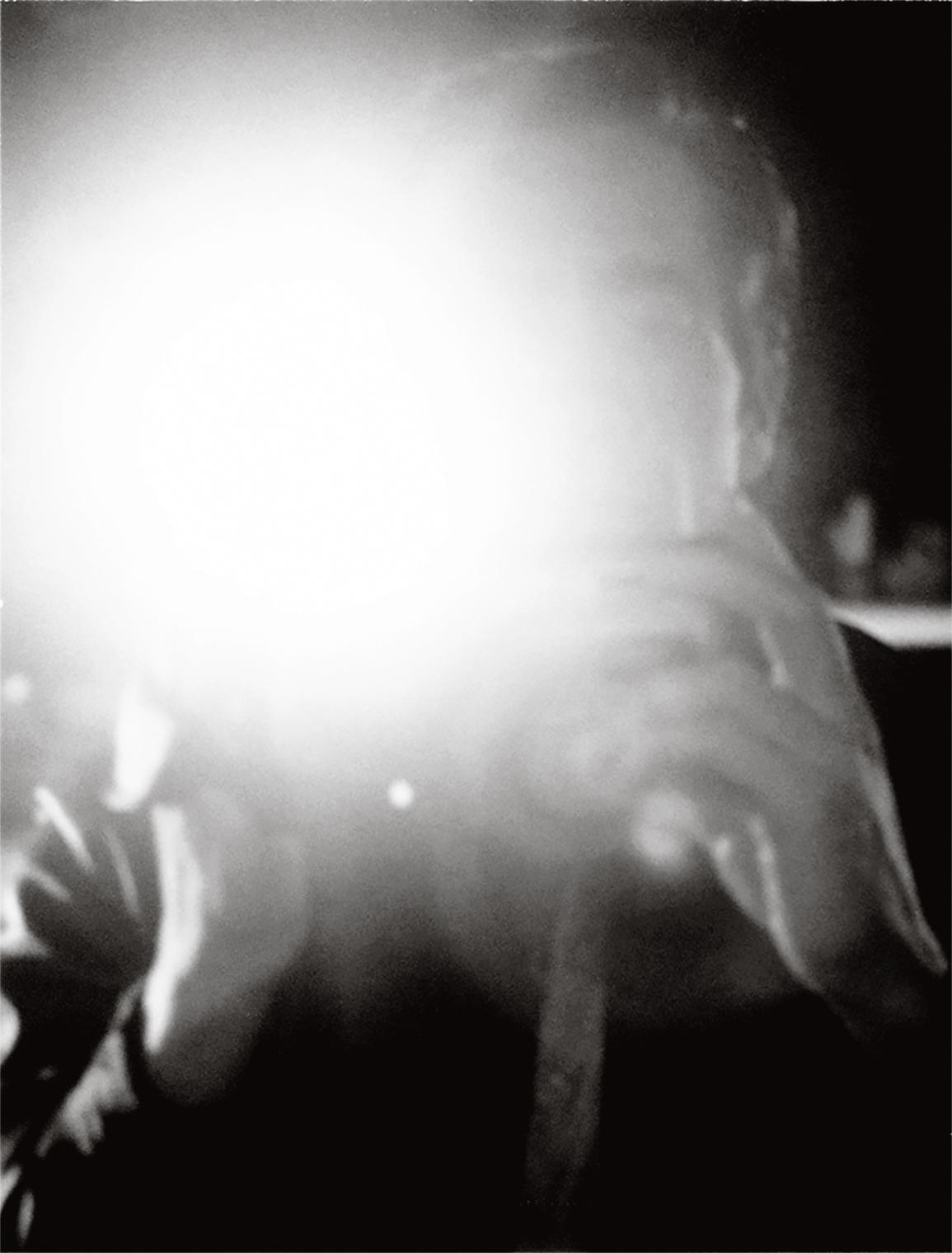

In one image from Ryan Spencer’s recent series There Is No Light at the End of the Tunnel Because the Tunnel Is Made of Light (2016), a man holds up a camera to the lens, as if to photograph the viewer. At least, we assume, based on the blinding white circle emanating from the object in his hands, that it must be a camera. In Spencer’s work, light obscures as much as it illuminates.

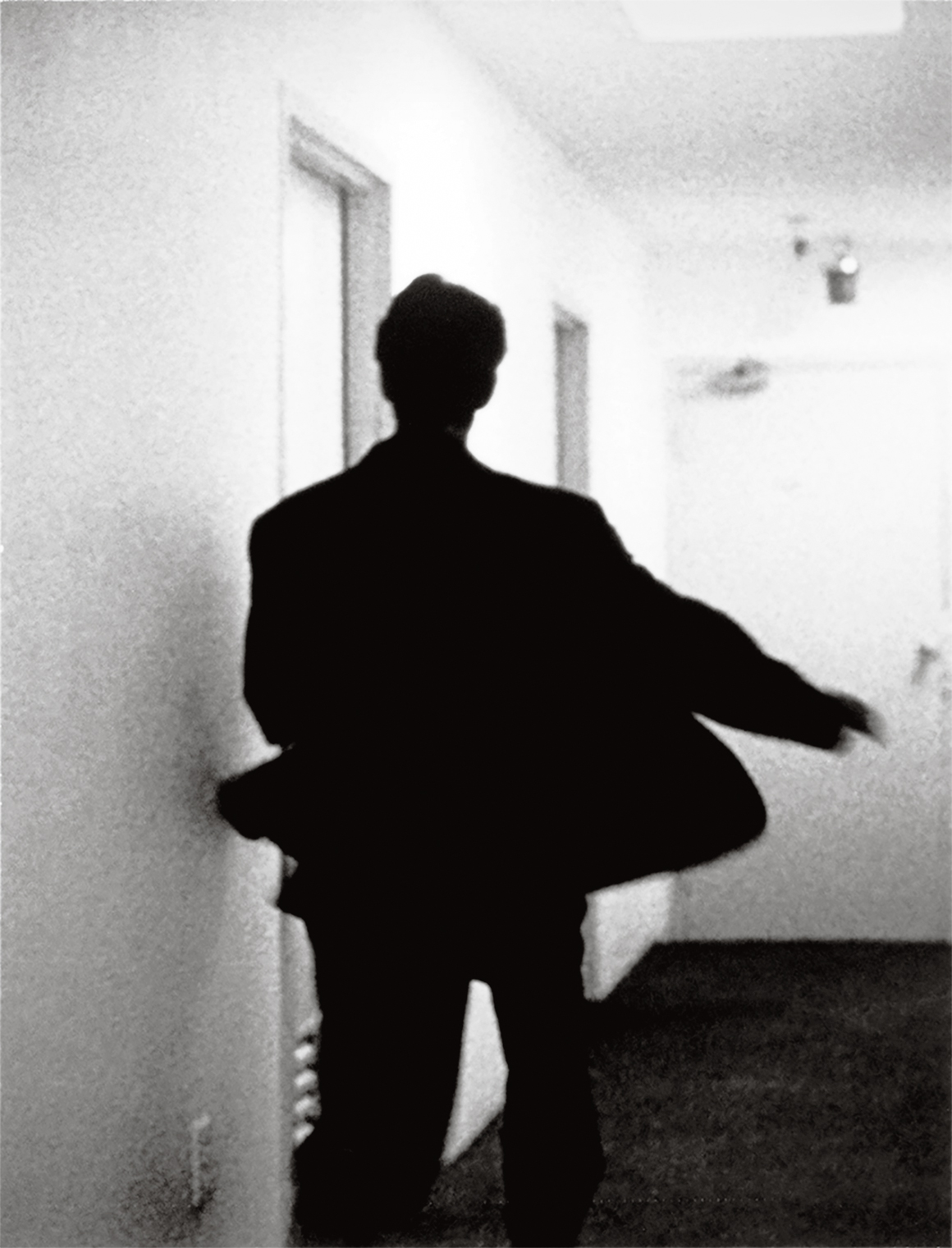

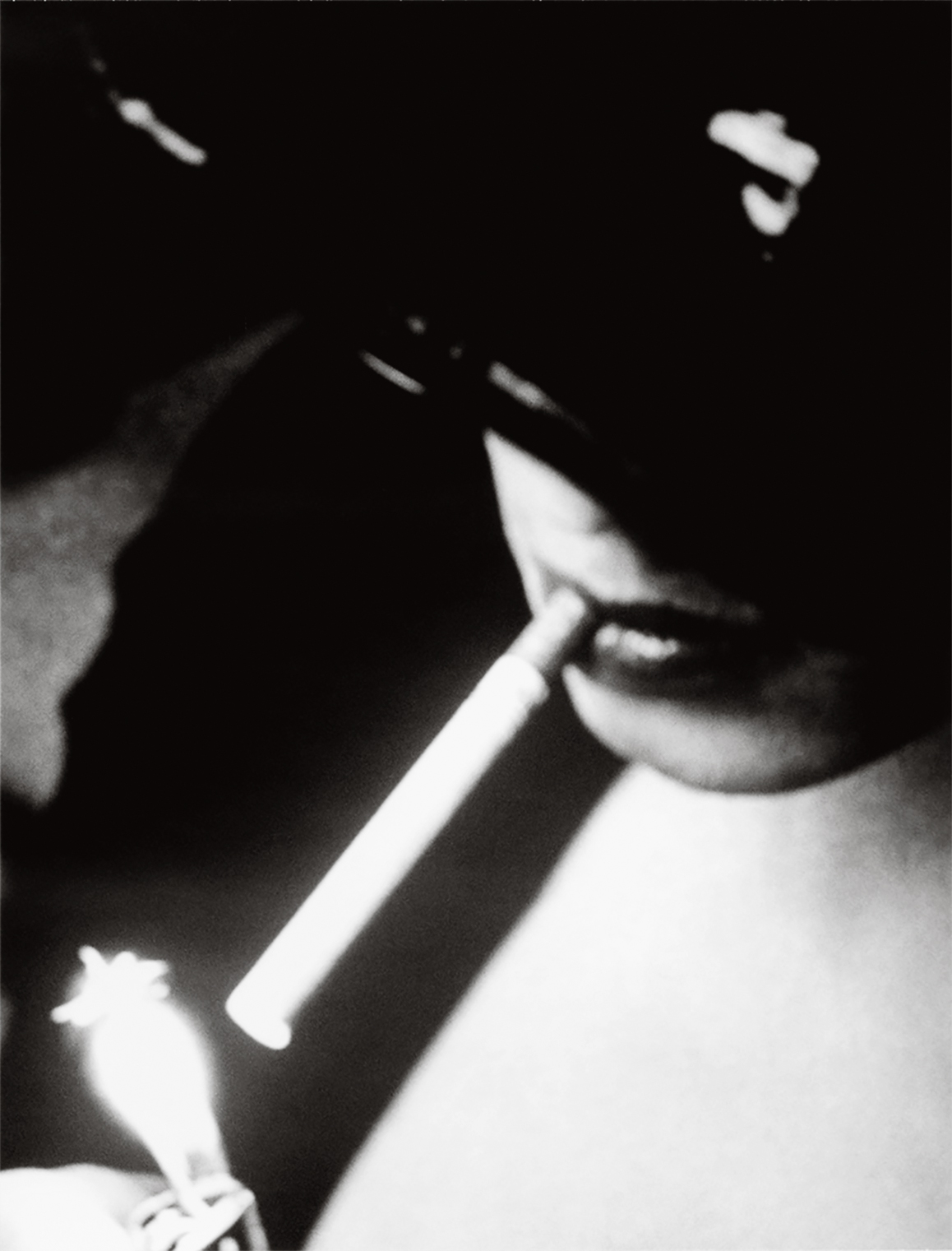

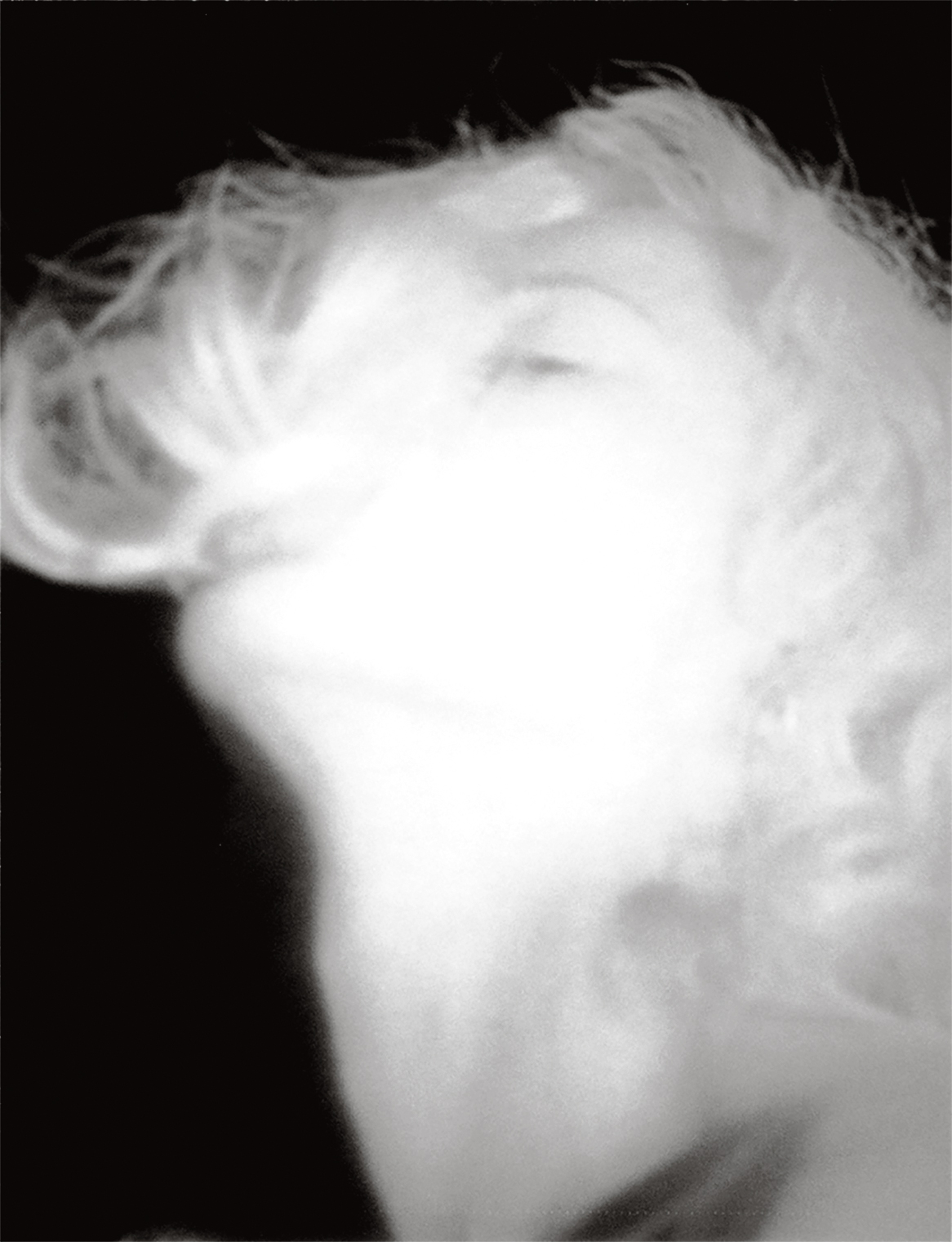

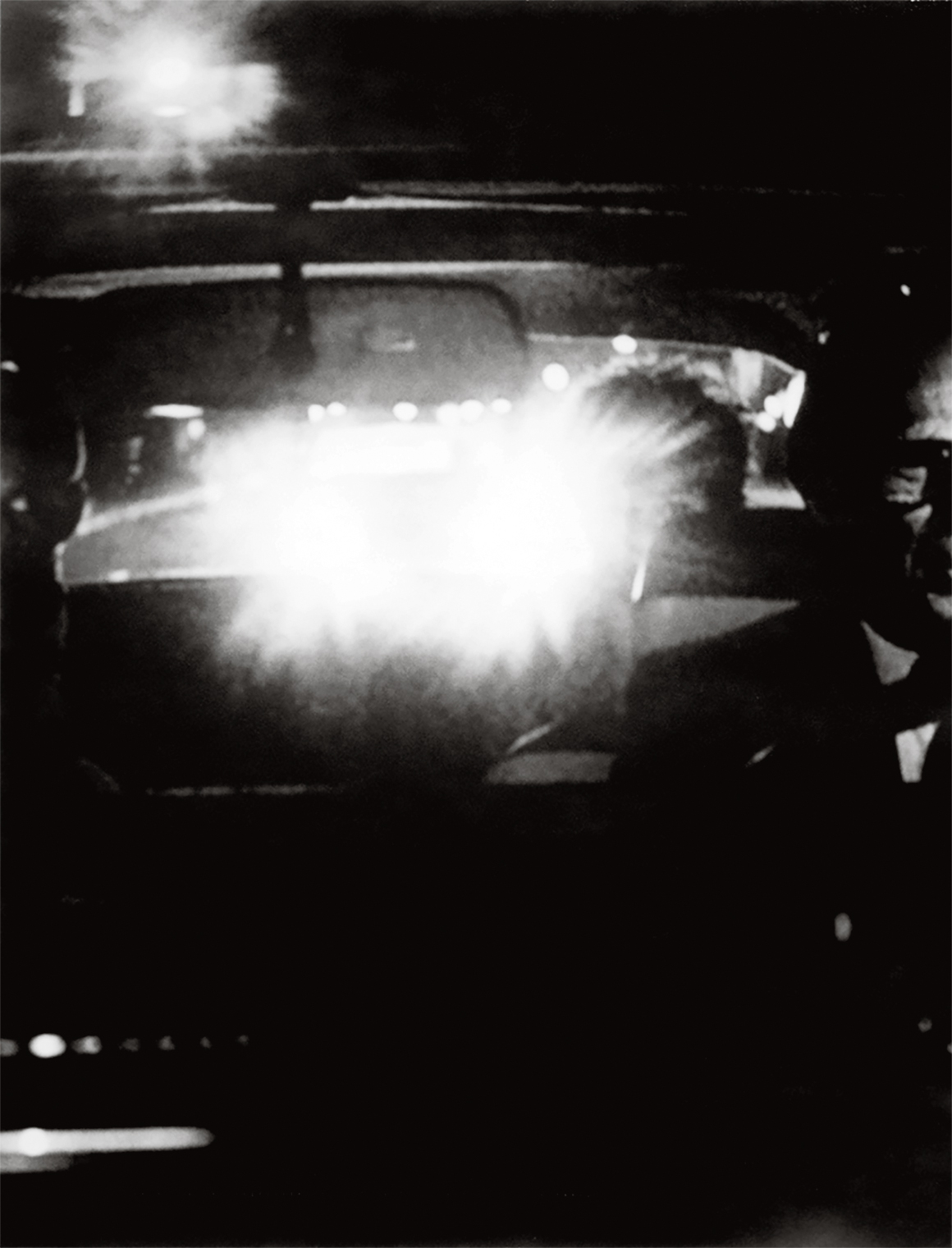

These pictures, taken with a 1970s-era Polaroid Land camera using Fuji FP-3000B instant film, capture still images from dozens of neo-noir movies set in Los Angeles. In this encounter between black-and-white camera and color TV screen, light takes on unexpected forms, sometimes enshrouding entire images in a pale gray wash—as in an image from Brian De Palma’s The Black Dahlia (2006) of a figure, perhaps a child, whose face and shoulders are barely discernible through a thick veil of what looks like smoke or fog—and sometimes creating a lens-flare halo that renders an otherwise sinister figure weirdly beatific. Such effects distort or mask the stills’ original meanings—Which movie is each image from? Does knowing the answer make a difference in how you see it?—and place them in the service of a new, obscurely glimpsed narrative. The ambient glare can suggest an interrogation room, a crime scene, or a traffic pull over. Spencer chose only movies made in the 1990s or later for a reason: reminders of the civil unrest at that time in Los Angeles, of the trial of O. J. Simpson and Los Angeles Police Department officers’ brutalization of Rodney King, thread their way through these unsettling photographs, many of which seem to either precede or immediately follow some decisive instant of transformation, be it sublime or terrible.

Courtesy the artist

The city whose archaeological traces these images show us, filtered first through the medium of narrative cinema and then through the gaze of one Polaroid-wielding viewer, never properly existed, on-screen or off. LA comes to life— lurid, uneasy, often menacing life—only in the meeting of these two recording media and the excess of luminosity their encounter produces. The photographs that stay with me most from this haunting series affect the viewer like the glowing eyes of a coyote in a still from Michael Mann’s Collateral (2004): they are both sources of light and holes into which our gaze disappears. Whether it emanates from a gun, a cigarette lighter, a glittering nighttime cityscape, or a mysterious offscreen source, the light in No Light functions as a doorway to some other space, behind or beyond the image itself.

This conversation between photography and movies was initially sparked by neither medium, but rather by a piece of music—Black Love, the 1996 Afghan Whigs album— that struck Spencer as “incredibly cinematic in its themes. I always thought of it unfolding as the suicide note of a doomed protagonist, sort of the way that Sunset Boulevard is told from the point of view of the narrator who we see floating dead in the pool.” The images in No Light arrive from a similarly impossible place; if they do form themselves into a story, it’s one told by a ghost.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, Issue 231, “Film & Foto.”