Santu Mofokeng’s Pensive Visions of Land and Ritual

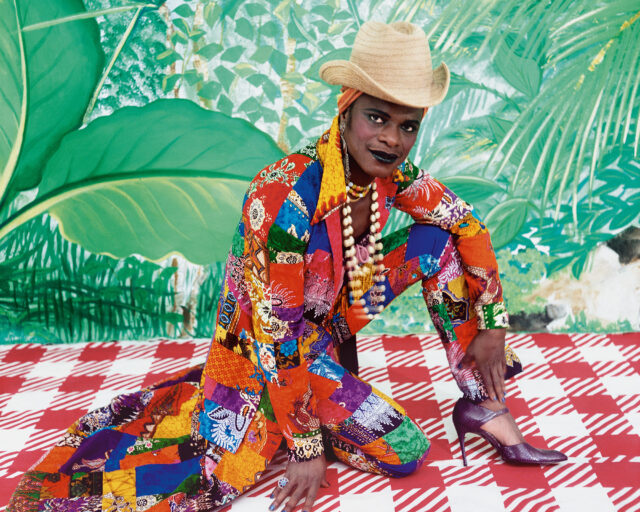

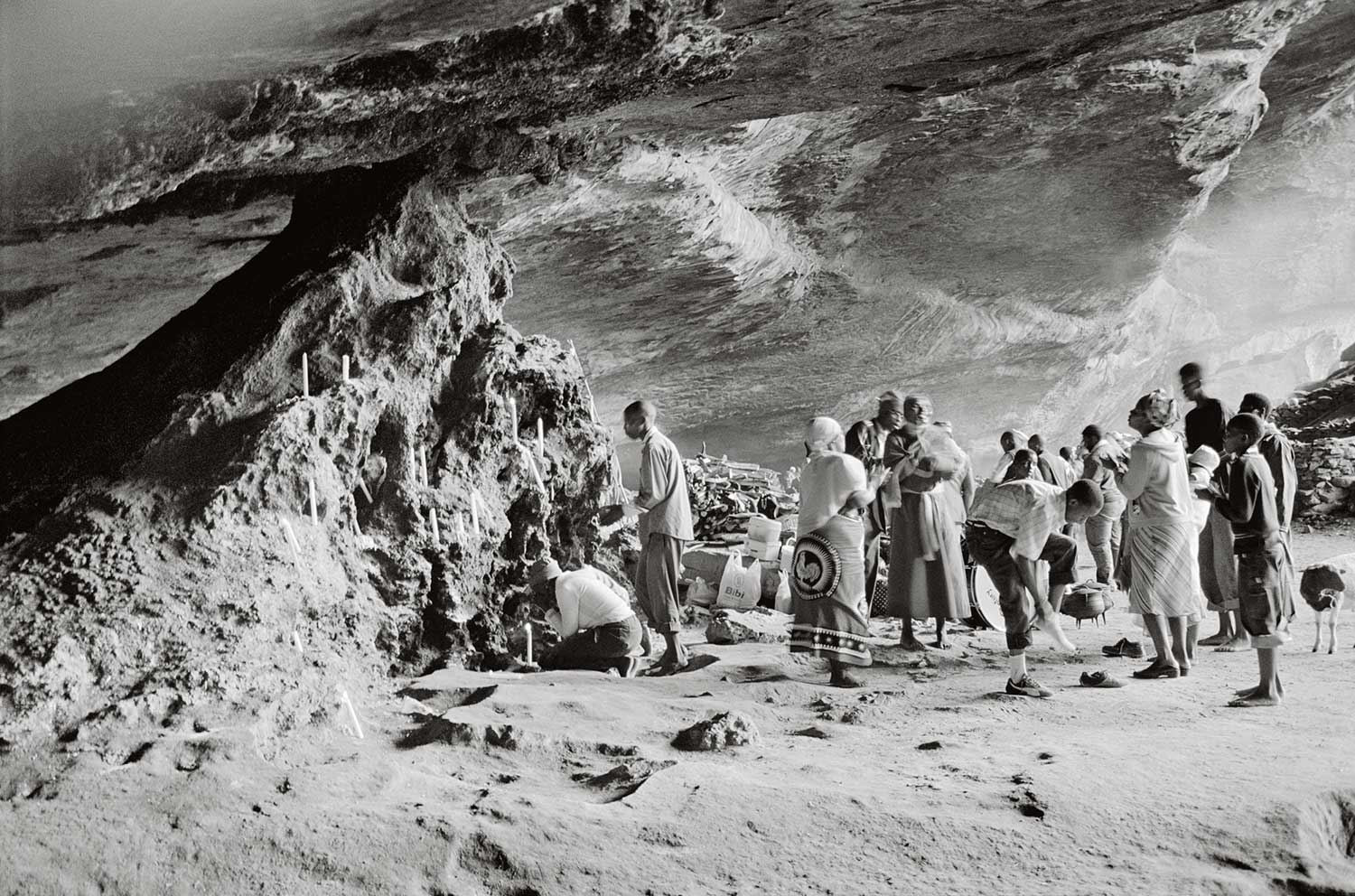

In October 2004, a few months after a handful of his black-and-white street photographs were presented in an exhibition of South African photography in Tokyo, Santu Mofokeng agreed to meet me at his Johannesburg home. The plan was to pick up on our conversations in Japan, as well as to talk about an image he had recently taken of his older brother Ishmael, which he was showing at a local gallery. Titled Eyes-Wide-Shut, Motouleng Cave, Clarens (2004), the head-and-shoulders portrait presents an aging man, with a graying Colonel Sanders goatee, wrapped in winter clothes. Two figures pass behind him, blurs in the murk of a cave. His eyes, too, are distorted, but it is nonetheless possible to detect a slight deviation in his sight. Ishmael’s right eye peers straight into the lens, but his left eye does not. It looks elsewhere, at something beyond the conjecture of words. Call it a decisive finality.

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

When I arrived at Mofokeng’s house, the photographer was slumped on the pavement, crying. Ishmael, he said, was dying. He motioned me into his home, pointed to a seat, and handed me a stack of postcard-size photographs. “My children cried when I showed them these.” The photographs, cheap machine prints, offered a sequential record of a road trip Mofokeng had recently undertaken with his brother to Motouleng Cave, an immense sandstone overhang near South Africa’s border with the mountainous country of Lesotho. The caves there are popular with hikers and urbanites interested in ayahuasca spiritual medicine—ceremonies. Motouleng, though, is different.

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

The cave, whose name in the central South African Sotho language loosely translates as “place of the beating drums,” has a special significance for followers of the country’s traditional animist religions. It is venerated as a place of salvation and healing. Ishmael had recently been diagnosed with tuberculosis, an opportunistic infection that is the leading cause of death among people with HIV.

“Of the many beliefs in townships, most people believe there are two kinds of HIV virus and AIDS,” Mofokeng wrote in 2011. “There is the genuine kind, identified worldwide by epidemiologists, which responds to treatment using scientifically approved methods and medicines. The other kind is transmitted by a ‘worm’ and is passed on to a person by witches, enemies, jealous relatives, friends, and so on.” Ishmael believed he was a victim of the latter, that his decline was attributable to witchcraft.

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

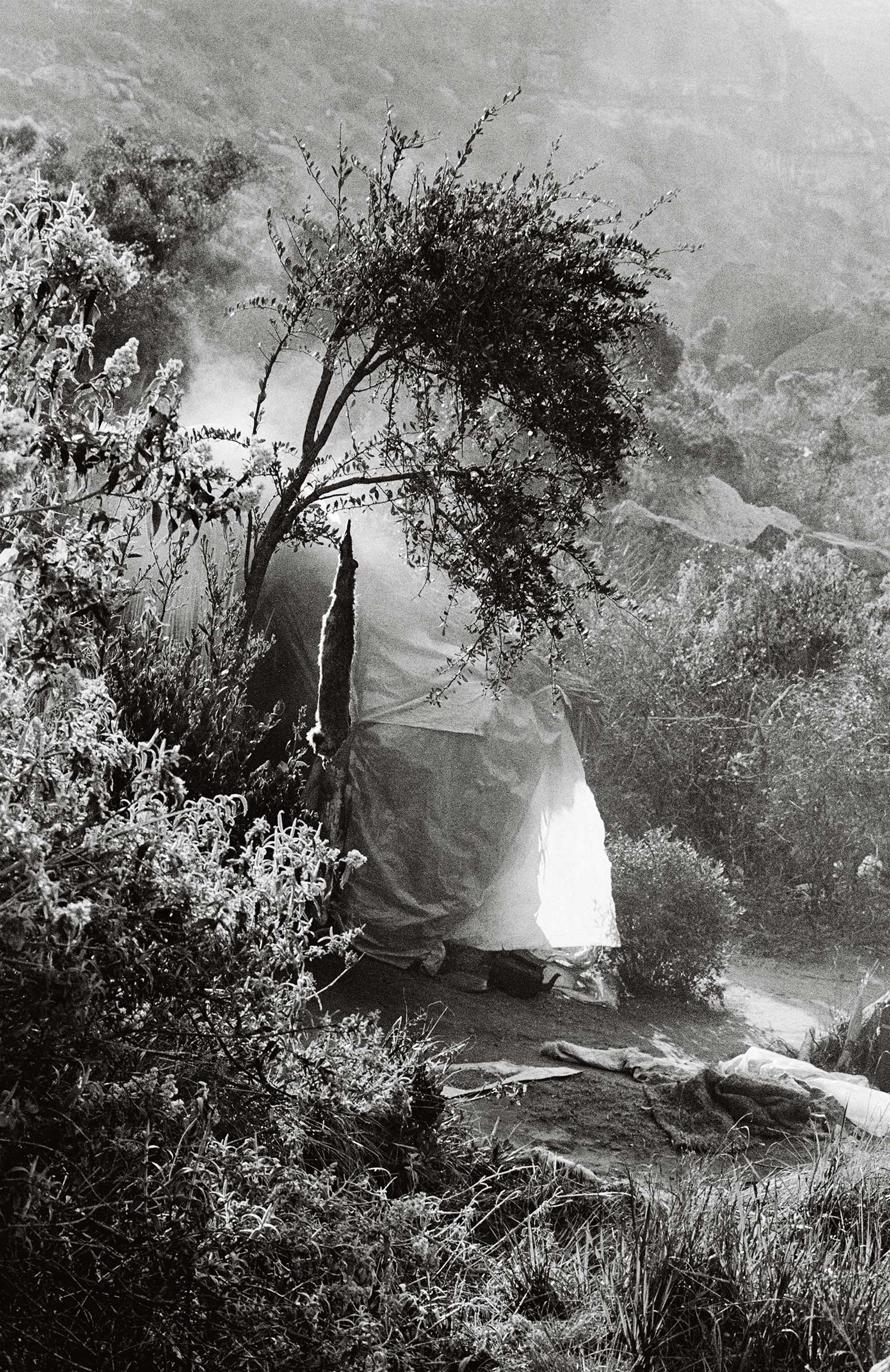

The drive from Johannesburg to Motouleng takes roughly four hours. The final approach is made on foot. It was an arduous trek for Ishmael, who avoided naming the illness that had brought him to the cave. He collapsed. One of the small photographs I cradled in my lap depicted this: Ishmael lying in a meadow, resembling one of the war dead photographed by Timothy H. O’Sullivan. Mofokeng bundled his brother into a wheelbarrow like a sack and pushed him to the cave, where, in the presence of resident healers and fellow pilgrims, he was fortified by the immensity of his encounter with tradition.

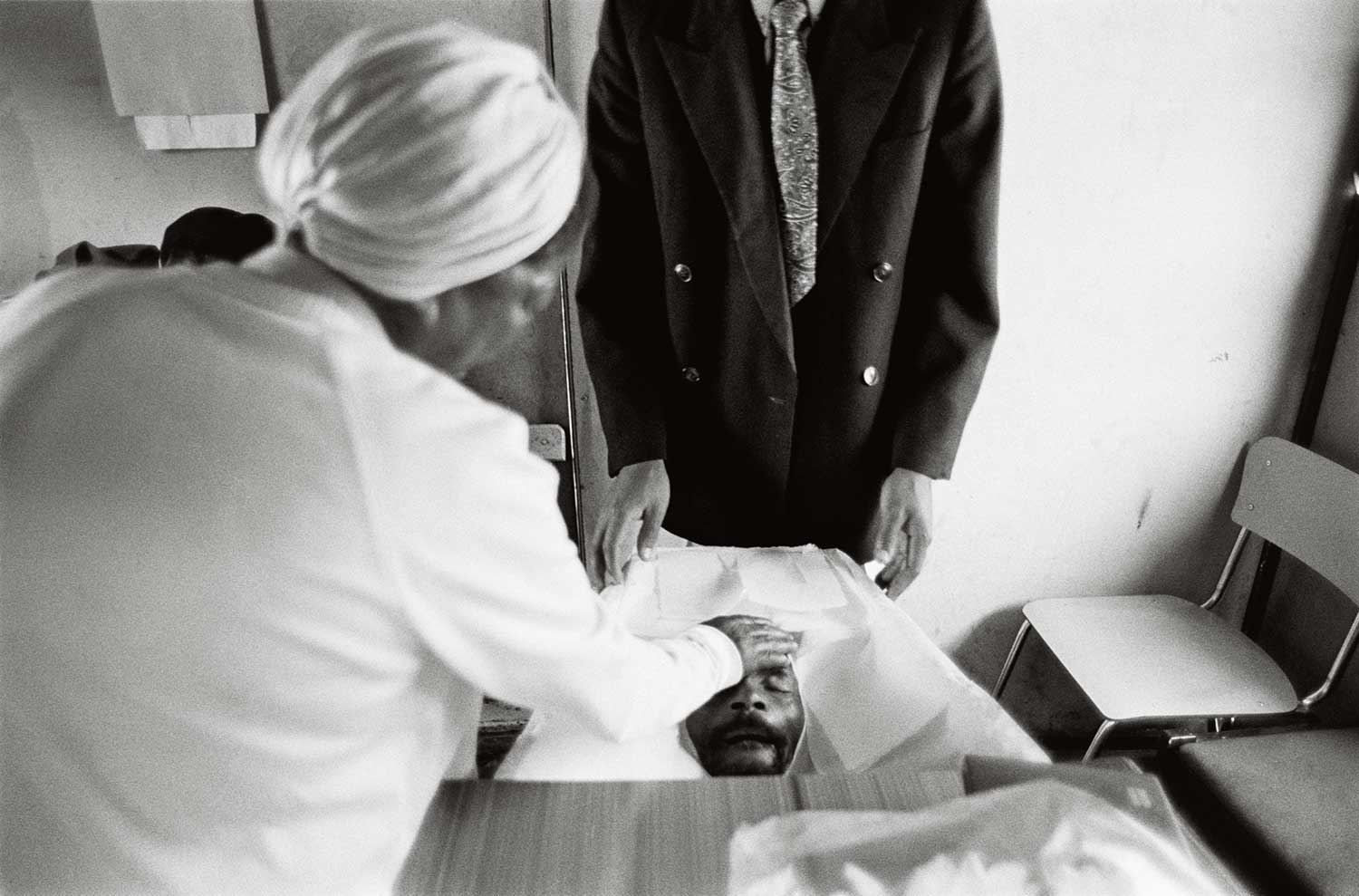

Three years later, in 2007, in a Johannesburg gallery during a walkthrough with me of Invoice, his first, largely self-curated survey exhibition, Mofokeng offered a shorn summary of his visit to the cave with his brother. “They gave him water and holy ash,” he said. “He felt better and said thank you to me for bringing him to Motouleng. He walked back to the car without assistance. It didn’t take him long, and he died. Anyway.”

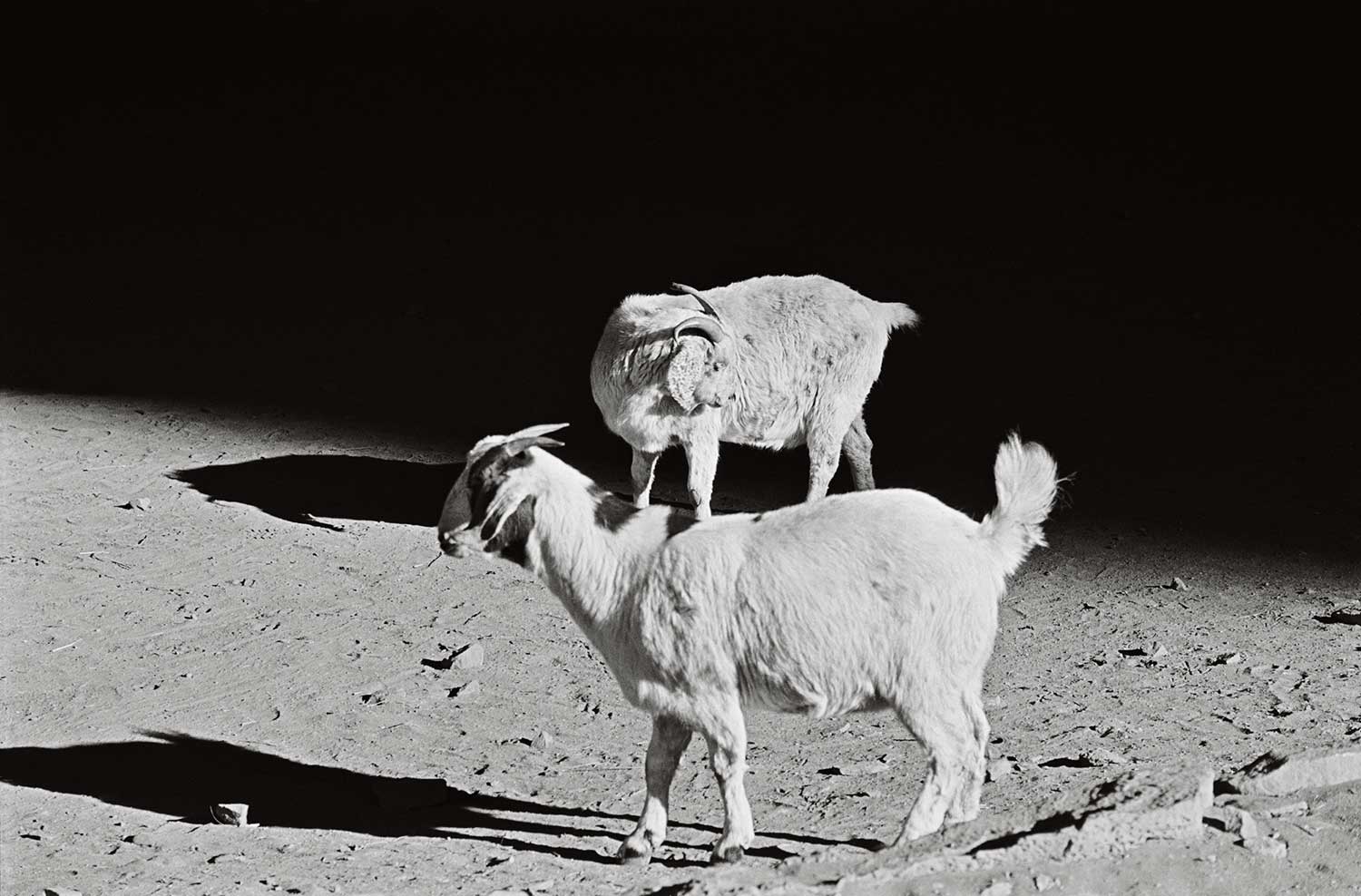

Mofokeng quickly moved on to another photograph, which depicted two goats, sacral animals roaming the same cave, in 2004. He pointed to the optical illusion at play, of one goat seemingly balancing on another. He linked the photograph to his portrait of Ishmael. “I don’t know if Ishmael’s eyes are open or shut.” These two pictures, along with another of a horse hidden in shadow taken near a Buddhist retreat in 2003, he explained, were descriptive of his attempt to photograph magic. “Can you capture it?” he asked. “No.”

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

*

Mofokeng is now sixty-three. His career is signposted by the standard markers of achievement—photobooks, exhibitions, awards, a growing body of interpretive writing—but among his peers, he remains something of an enigma. Make no mistake: Mofokeng is widely admired, particularly by younger South African photographers like Jabulani Dhlamini and Lindokuhle Sobekwa, but he is not a household name, at least not like his elder, the renowned South African photojournalist Peter Magubane.

“I find the term so weird, a painter’s painter, but if I was asked who is a photographer’s photographer, I’d say Santu,” explains the artist Mikhael Subotzky, who as a young man looked to white South African photographers working in a humanist, rather than activist, tradition of documentary—notably David Goldblatt and Guy Tillim—as models. “I am trying to think if there was a reason why,” he adds. “In some ways, it was as simple as Santu’s work wasn’t as accessible to me.”

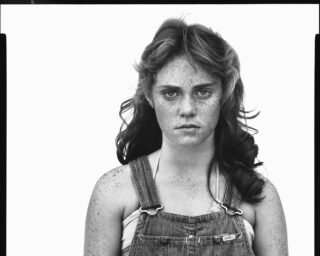

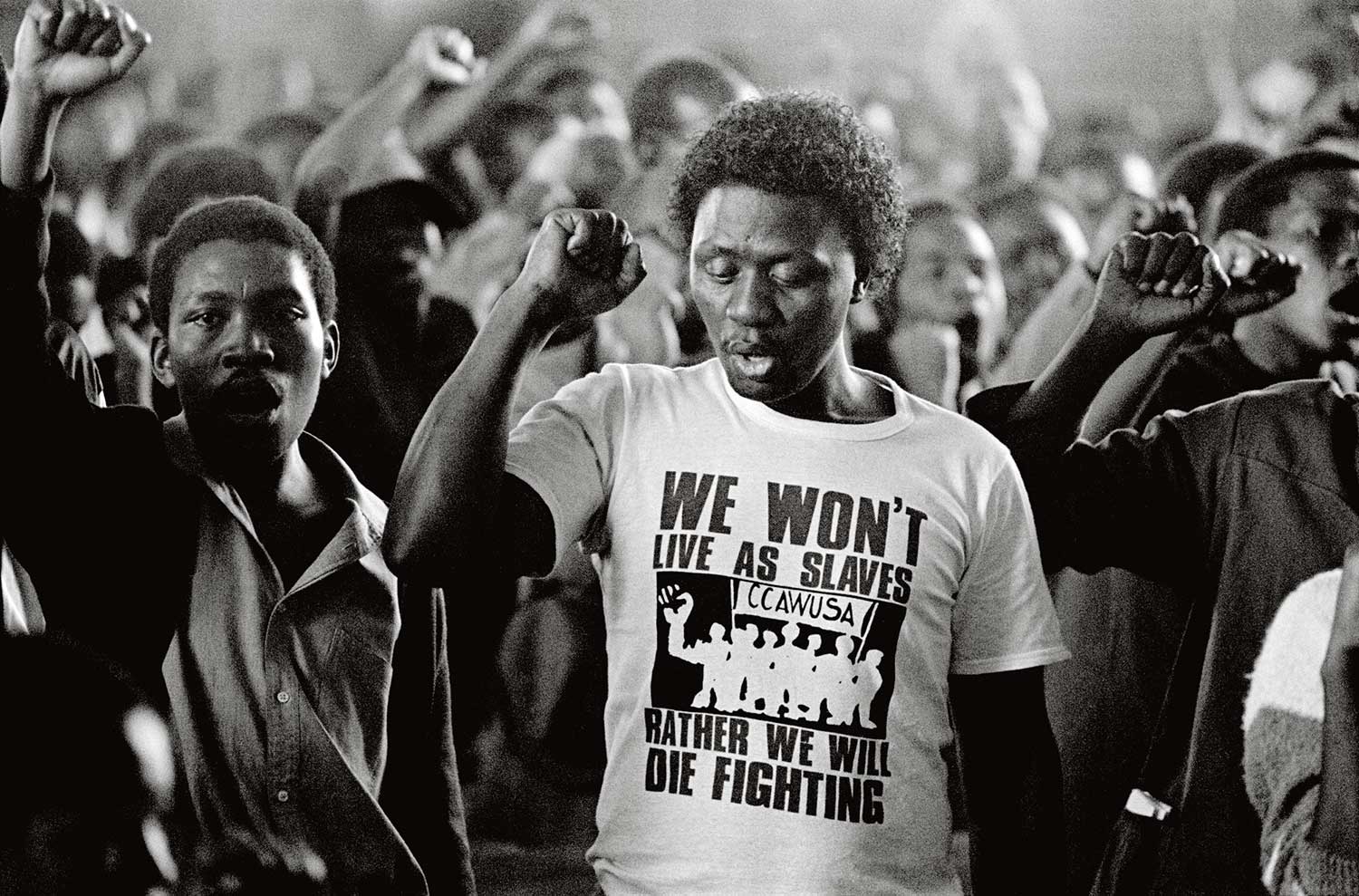

There are various reasons Mofokeng’s work hasn’t always been available. He initially worked in news, that most ephemeral of photographic modes, covering the civil strife that gripped South Africa in the 1980s, the final decade of apartheid. Mofokeng tired of the genre’s rhetorical conventions, of producing “images bespeaking gloom, monotony, anguish, struggle, oppression,” as he wrote in 1993, and joined the African Studies Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits). Starting in 1988, he spent most of the next decade working in relative obscurity, documenting rural tenant farmers, collecting photographs of South Africa’s forgotten black middle class, and—crucially—refining his writing skills.

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

Mofokeng worked with the revisionist historian Charles van Onselen at Wits. The environment of the institute, which Mofokeng described as “enabling,” cultivated in him a belief in his photographs’ value. It also highlighted the need to answer basic questions: What are you doing? Is this what you mean? Coming up with explanations wasn’t easy—writing was not Mofokeng’s métier, at least not initially—but the process allowed him to take ownership and responsibility for his photographs.

In 1996, he signaled the end of this withdrawal by initiating his long-term project photographing in the caves that would later attract his brother. “When I first became a professional photographer, I started working on a project called Fictional Biography, a sort of metaphorical biography of my life, going to places I would ordinarily go, making photographs of things I ordinarily do or see,” Mofokeng told the Swiss curator and art historian Corinne Diserens in 2011. Entering the caves, he said, was his way of concluding a body of work he had started in the mid-1980s.

In 2002, Mofokeng’s photography was featured in the curator Okwui Enwezor’s landmark Documenta 11 exhibition in Kassel, Germany, and, almost a decade later, Diserens organized the first international survey of his work, Chasing Shadows: Santu Mofokeng, Thirty Years of Photographic Essays (2011). Comprised of some two hundred photographs, and presented first by the Paris photography space Jeu de Paume, followed by a multicity European tour, the exhibition was organized into loose thematic clusters. Heralded by Train Church (1986), his breakthrough series of close-up portraits of religious worshippers on crowded passenger trains in Johannesburg, and fully announced by Chasing Shadows (1996–2014), a photographic essay largely made in the caves of central South Africa, Mofokeng’s interest in spirituality formed a major component of the survey. The latter essay, with its explicit focus on spirituality, includes his portrait of Ishmael. “Once in a while I make portraits,” Mofokeng told Diserens in an interview, “and some of them I’m proud of, but I can’t say I’m a portrait photographer.”

Each section of Diserens’s exhibition was introduced with text panels written by Mofokeng. They reiterated a long-held faith. “Most of the time, when I’ve looked at catalogues or exhibition texts in which experts come in and talk about my work, I don’t like it,” Mofokeng told the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist in 2002. “I was raised by a parent (my father died when I was four) who instilled in me a religious thing about always searching for meaning and purpose in everything we do. This informs my enterprise and the work that I do—I’d like to be the interpreter of my work.”

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

*

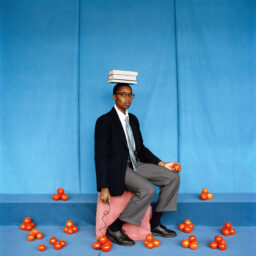

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, a twenty-four-year-old Magnum Photos nominee, tells a story about a visit with Mofokeng around 2013: “I wanted to show him my best pictures, which I had printed out. He looked at a few pictures. ‘You can photograph, but what have you written?’ I said nothing. ‘Take those newspapers and go read. Next time I meet with you, show me what you’ve written.’ I was very young, and I thought photography is something you don’t need to read or write about. He was teaching me.”

Sobekwa first encountered Mofokeng’s work while studying photography in high school. His teacher showed him a copy of Chasing Shadows. He says he felt a connection looking at the images. In an essay appearing in the book, Enwezor describes Mofokeng as “heir to the great black South African photographers such as Alf Khumalo, Peter Magubane, Ernest Cole and Bob Gosani, as well as to David Goldblatt.” He writes that “Mofokeng’s observational approach, his scrupulous skepticism toward the dramatic image,” is most allied to the “urban disquiet” of Cole and the “cool distance” of Goldblatt.

Mofokeng contradicts this. Magubane’s documentation of the apartheid government’s violent crackdown on a 1976 student revolt in Soweto, conceived in the 1930s as a segregated black settlement abutting Johannesburg, was particularly influential. “It was Magubane who made photography a respectable occupation,” Mofokeng told me in 2014. While Goldblatt was “an inspiration,” he said it was while working as a printer for Magubane’s mentor, the German-born photojournalist and documentarian Jürgen Schadeberg, in 1986, that he had a “light-bulb moment.” His series Train Church, made while journeying by train to and from work with Schadeberg, materialized this insight. Its blurred chiaroscuro lighting became a hallmark of Mofokeng’s photography.

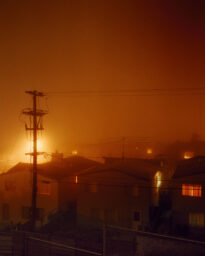

South Africa’s passage to a nonracial democracy, however imperfect, has tended to inspire fabulist narratives about the role of color film in portraying the fullness of the new country. After the first nonracial elections in 1994, documentary photographers started to use color more frequently. By 2000, as South African photography gained wider visibility, some artists and critics began to argue that black-and-white imagery was ethically oppressive and, conversely, that color was dignified. Mofokeng rejected this argument as expedient and market-driven. In a 2013 note he explained how “my work and that of lefties, groups and archives, and other activists and organizations, along with their efforts, were being insulted and thrown out like so much apartheid paraphernalia and baggage.” The meaning of color in postapartheid photography certainly merits consideration, but not at the expense of some basics. While his black-and-white images are better known, Mofokeng also worked in color; selections from his color landscape series Graves (2012) were shown at the 2013 Venice Biennale.

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

*

The Cape Town–based photographer Jo Ractliffe first became aware of Mofokeng around the time he joined the nonracial and activist inclined photography collective Afrapix, in 1985. Best known for her ravaged landscape pictures depicting the troubled passage to freedom in South Africa, Namibia, and Angola, Ractliffe doubts the curatorial projection of thematic certainties onto Mofokeng’s work. She describes his fragmentary and investigative output as hard to pin. “People tend to make his work seamless in a way that I don’t think it is at all,” she says. Ractliffe considers Mofokeng not coherent in the way Goldblatt was coherent, or his contemporaries at Afrapix were. She singles out his first book of photographs, Taxi-004: Santu Mofokeng (2001), an unpolished hodgepodge of text and image that the photographer played a key part in orchestrating.

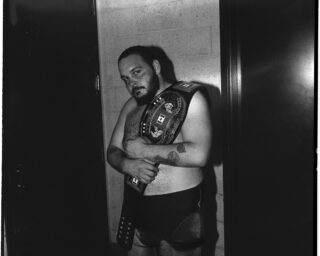

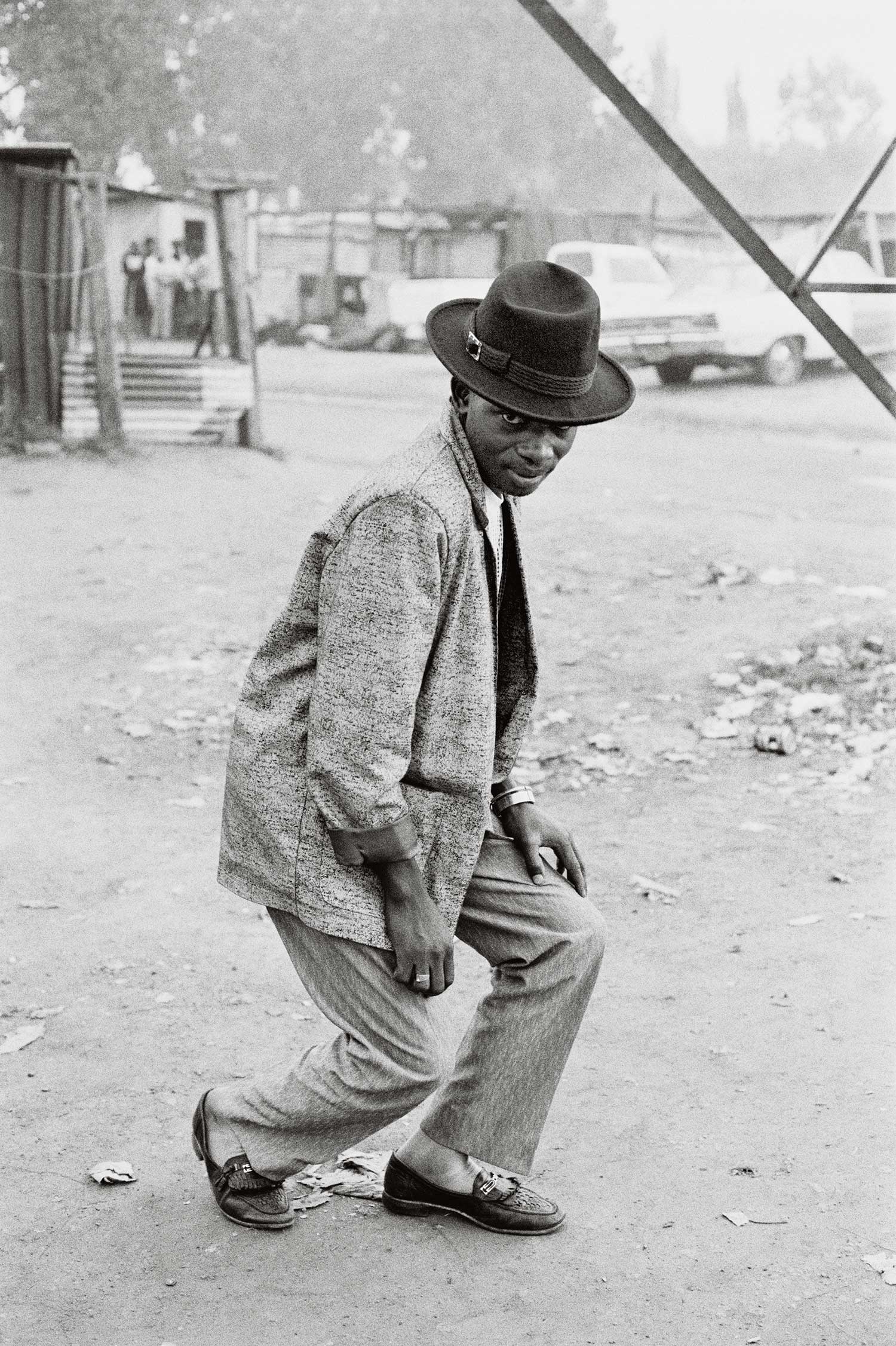

“Books are a way of domesticating meaning,” Mofokeng has stated. For all its failures, his first book is nonetheless striking for an autobiographical essay titled “Lampposts,” which threads through the layout, making a case for the equal import of Mofokeng’s writing. The essay details his impoverished upbringing in Soweto, his introduction to photography in the early 1970s, his careers as a darkroom technician and a photojournalist in the 1980s, his vague immersion in activism, as well as his subsequent pursuit of a personal vision. It even features an episode involving Ishmael, who, in 1976, saw his younger brother being beaten by white bullies on the streets of Johannesburg’s city center in retaliation for protests in nearby Soweto. “I was never an activist,” writes Mofokeng. His photojournalism from the late 1980s, nonetheless, includes strongly partisan documentation of street protests, striking mine workers, and police repression, as well as the tenth-anniversary commemoration of the 1976 Soweto uprising.

This long-ago-forgotten activist work forms part of the photographer’s new twenty-one-volume anthology, Santu Mofokeng: Stories (2019). The outcome of a multiyear collaboration between Mofokeng, the bookmaker Lunetta Bartz, the editor and New York Public Library curator Joshua Chuang, and the German publisher Gerhard Steidl, the series is a major restatement of Mofokeng’s career. Its selection of 584 photographs draws upon an archive of approximately 32,000 frames. The earliest photographs date back to 1985; the most recent are from 2011. There is a somber finality to this closing bracket. In 2013, Mofokeng began to lose his voice. He was later diagnosed with a degenerative illness known as progressive supranuclear palsy. He is now confined to a wheelchair, unable to speak.

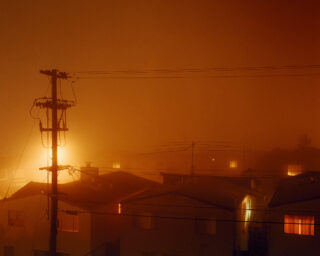

Stories is a major expansion of the public archive of Mofokeng’s practice, but in other ways it also efficiently clarifies older work. Photographs that once appeared singular, or unhinged from context, or too instrumentally bound to grand themes of struggle and belief, are now revealed to have emerged from very particular projects. Some have to do with indigenous customs (Pedi dancing) and localities (notably, Soweto and Bloemhof), and were made over a number of years. Others, though, are strikingly time-bound—like Concert at Sewefontein, his experiential photo-essay on youth and pleasure in rural South Africa on a Friday night in 1988, or Funeral, a remarkable sequence on the tenant farmer Miriam Maine’s burial on November 21, 1990.

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

Stories includes two volumes devoted to Mofokeng’s work between 1996 and 2010 in Motouleng and Mautse Caves. “I grew up on the threshing floor of faith,” writes Mofokeng in the introduction to the volume titled Caves. (The books are otherwise spare in design, and most don’t contain captions.) “A faith that is both ritual and spiritual—a bizarre cocktail of beliefs that completely embraces pagan rituals as well as Christian beliefs. And while I feel reluctant to partake in this gossamer world, I can identify with it.” This passage is from a 2011 text he wrote for Chasing Shadows. The word reluctant is telling. Mofokeng’s work in the caves was bound by an ambivalence and an agnosticism; this attitude framed his participation in a ritual he understood intimately, but could not believe in.

“Apartheid was a roof,” Mofokeng wrote in a text accompanying his exhibition Invoice. “The demise of apartheid has brought to the fore a crisis of spiritual insecurity for the many who believe in the spiritual dimensions of life. Today, this consciousness of spiritual forces, which helped people cope with the burdens of apartheid, is being undermined by mutations in nature. If apartheid was a scourge the new threat is a virus; invisible perils both.”

With these lines, Mofokeng manages to invoke white oppression, black faith, and the medical crisis of HIV/AIDS in postapartheid South Africa as germane themes for understanding his cave studies, including the portrait of his brother. His explanation cuts across past and present time, challenging assumptions that his photographs operate as discrete meditations on particular moments or themes. Everything connects in Mofokeng’s understanding, however tangentially. To corrupt a verse from Walt Whitman, his photography is best understood as contradictory, large, and containing multitudes.

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

*

During a digressive conversation at his home in 2003, Mofokeng told me that Ishmael looked like someone “from Biafra or Somalia.” His description implicitly summoned the emaciated specters that haunt the careers of war chroniclers like Don McCullin and James Nachtwey, agonizing and exposing images that Mofokeng came to reject while working as a photojournalist. His rejection is clarified by his steadfast allegiance to his birthplace. For Mofokeng, Soweto was far more than an apartheid ghetto.

“I feel a peculiar sense of pride and belonging—also grounding—in coming from that space and of contributing to its history,” he wrote in 2011. Mofokeng often refers to Soweto. In 1993, in a text for a photography festival in Herten, Germany, organized by Das Bild-Forum, he likened Soweto’s historical portrayal to that of conflict hot spots like Somalia and Bosnia. He railed against the way “gruesome” photographs of struggle “have come to possess a kind of comforting familiarity for international audiences. People assume they know not only what Soweto looks like, but what it is to live there. Well, yes and no.”

Mofokeng does not reject the existence of oppression, violence, and squalor; it is just that these are “partial realities, which do not encompass people’s lives,” he wrote. “It is an irony that the endless repetition of these familiar images serves to exclude other kinds of violence and misery.” Reality, he would later comment, “is much more complex.” It involves, as he put it, ordinariness and “quotidian life.” This pithy phrase surfaces as a defining leitmotif of Mofokeng’s work, which over the past four decades has eloquently and insistently anatomized themes of home, work, and faith within a framework of servitude.

Notwithstanding the achievement of universal franchise in 1994, South Africa remains glaringly unequal. Made between 1988 and 1994, Mofokeng’s photographs of black tenant farmers living on white-owned farms near Bloemhof, an agrarian community three hours west of Johannesburg, visualize this inequality with searing intensity. Mofokeng was directed to photograph in Bloemhof by the university, but his work exceeds mere commission. Analysis is leavened with empathy, with Mofokeng wresting insight through his insistent return to, and genuine connection with, his dispossessed countrymen.

In 1996, Charles van Onselen published The Seed Is Mine (1996), a book-length portrait of Kas Maine, a tenant farmer, healer, and community patriarch. The cover of the original hardback edition features a brooding portrait of Maine, taken by Mofokeng, wandering through an unidentified range. His photograph speaks of the right to roam, to possess, to be, conditions that were—and still to a degree are—legislated and policed. “Life transcends bureaucratic notation and legal formulations,” writes Van Onselen in his magnum opus. “Words—no matter how precisely chosen—mislead, phrases obscure, and sentences deceive.” Mofokeng’s immersive but also pensive photographs, which describe and acknowledge as much as they report and indict, fill in what words cannot quite register about South Africa—its ongoing dilemma of dispossession and penury, the quest for home and spirit.

Read more from Aperture issue 237, “Spirituality,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.