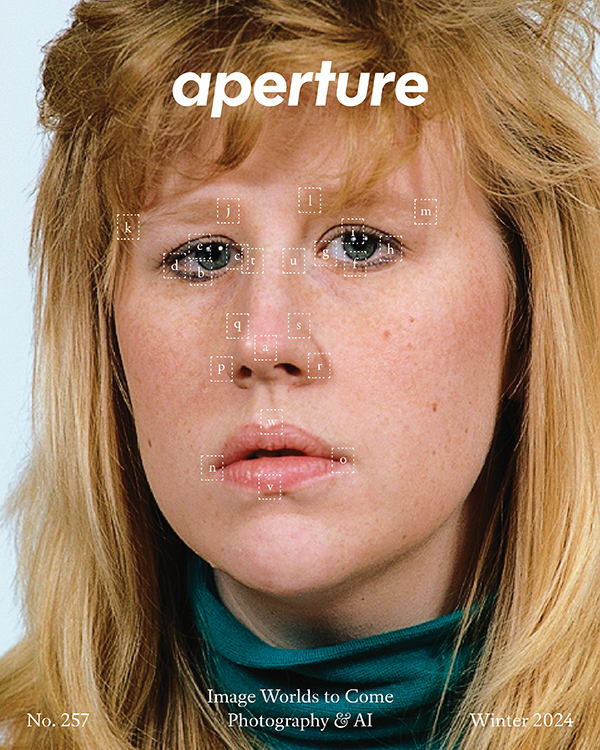

A Short History of the African Photobook

For Bronwyn Law-Viljoen, publisher of Fourthwall Books, the photobook is a space for political and social history.

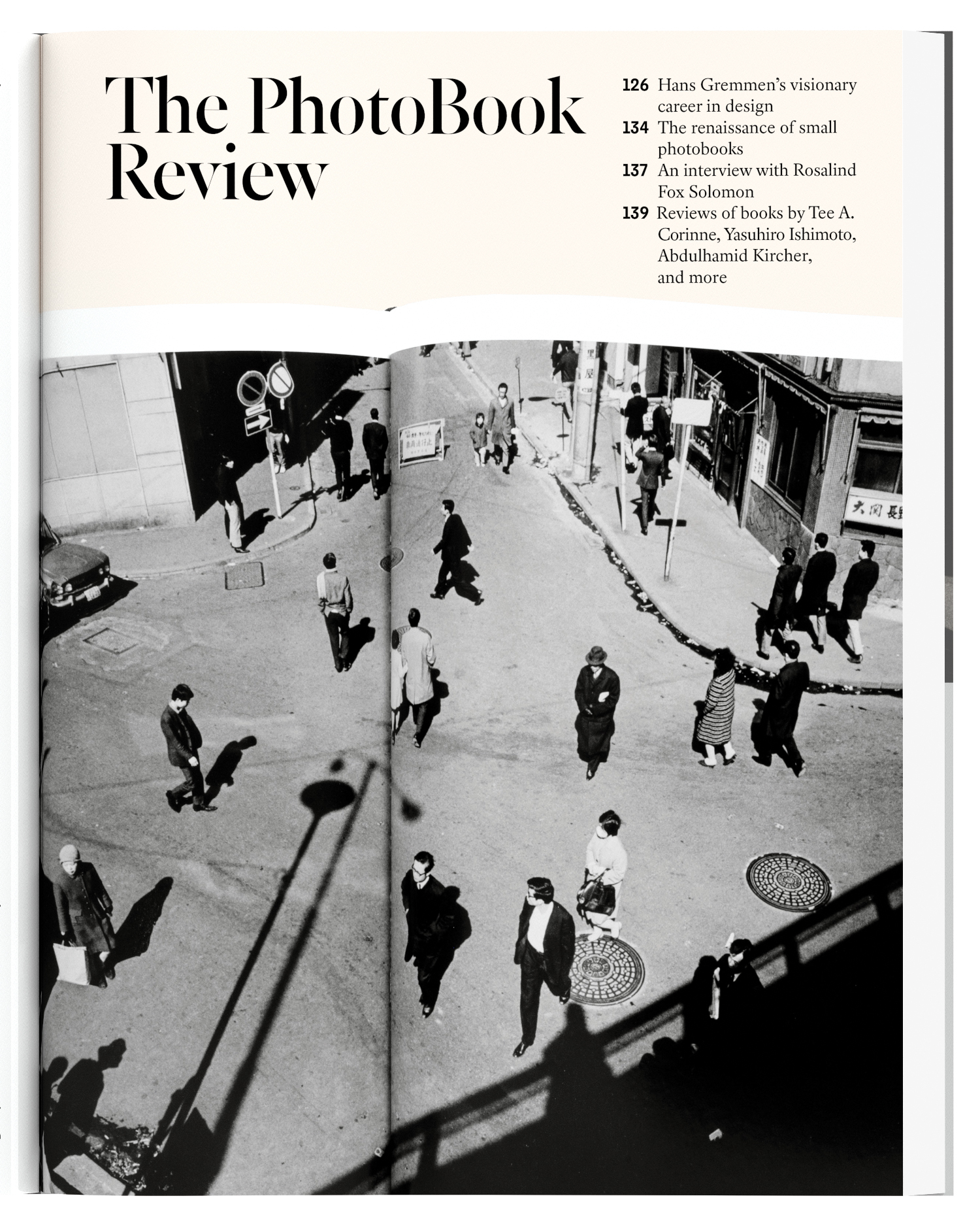

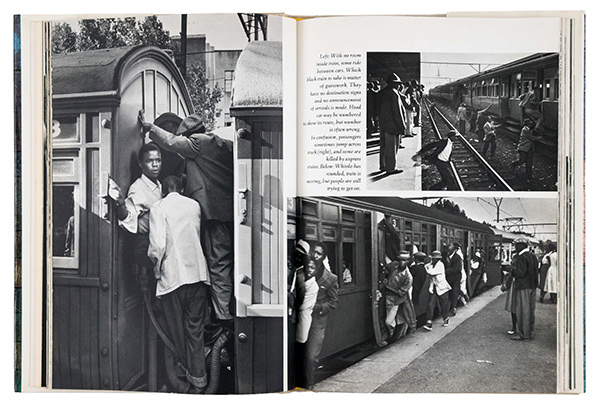

Spread from Hââbré: The Last Generation (Fourthwall Books, 2016)

Courtesy the artist and Fourthwall Books

One balmy night last November, a bus arrived at 44 Stanley, a shopping center in Johannesburg, and out poured a throng of artists, photographers, and writers to attend a party at the pop-up shop for Fourthwall Books. Bronwyn Law-Viljoen, who together with photographer and Fourthwall co-director Terry Kurgan, hosted the gathering on the occasion of Black Portraiture[s], the roving biannual conference on African and African American art that was then taking place at Johannesburg’s Turbine Hall. Fourthwall is known for intelligent, sometimes experimental books by African artists in which the texts are a crucial element. (Law-Viljoen—who grew up in Johannesburg, studied literature at New York University, and was once a work scholar at Aperture Foundation—recently published her first novel.)

Like any photobook publisher, Fourthwall, which was founded in 2010, is fueled by a sharp sense of idealism. The night after the Fourthwall party at 44 Stanley, Law-Viljoen spoke at Black Portraiture[s] about the history of the photobook in South Africa—a history to which she is now contributing through her titles and also the Fourthwall Books Photobook Award, inaugurated in 2016. But she opened her remarks by recognizing the community of photobook enthusiasts who had found their way to Fourthwall. “Sometimes you feel like you’re working all alone,” she said. “But last night, I felt as though people appreciate our work. They understand what we’re trying to do. And that was gratifying.”

In addition to being a publisher, you’re also a writer and a scholar. So, let’s start with a history lesson: what have been the most influential photobooks in South Africa? How have South African photobooks contributed to visual culture in Africa at large?

Bronwyn Law-Viljoen: If we’re talking about the period before the end of apartheid in 1994, then these are some of the most influential photobooks in South Africa: Ernest Cole’s House of Bondage [Random House, 1967]; David Goldblatt’s On the Mines [with Nadine Gordimer, Struik, 1973]; George Hallett’s Present Lives, Future Becoming [with Cosmo Pieterse, Hickey Press, 1973] and Images [BLAC Publ. Houses, 1979]; Peter Magubane’s Black as I Am [with Zindzi Mandela, Guild of Tutors Press, 1978]; and Roger Ballen’s Platteland [Quartet Books, 1994]. Since 1994, there have been books by Santu Mofokeng, Jo Ractliffe, Guy Tillim, Mikhael Subotzky, Sabelo Mlangeni, Pieter Hugo, Zanele Muholi, and others that occupy a very important place in contemporary South African photography.

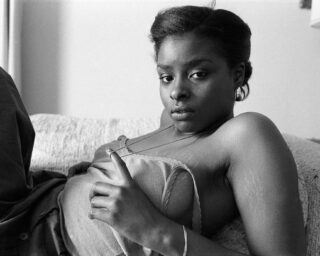

© the artist and courtesy Steidl

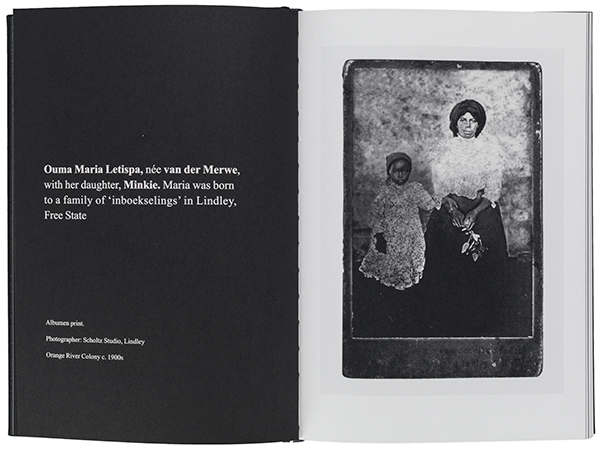

Santu Mofokeng’s The Black Photo Album/Look at Me: 1890–1950 [Steidl, 2013] and Guy Tillim’s Joburg: Points of View [Punctum, 2014] and Petros Village [Punctum, 2006] are almost like novels or concept books—they’re keys to unlocking a larger body of work. But younger artists have also used the photobook to communicate urgent social issues, such as prison conditions in Mikhael Subotzky’s Beaufort West [Chris Boot Ltd., 2008], and the stories of LGBTQ individuals in Zanele Muholi’s two books from her series Faces and Phases [Prestel, 2010 and Steidl and the Walther Collection, 2014] and Sabelo Mlangeni’s Country Girls [Stevenson Gallery, 2010].

Law-Viljoen: There is a very clear sense of history in all of the photographers you mention, and not just political history, but also photographic history. They have inherited a political and historical narrative, as well as the desire to tell “stories”—not only about the past, but also about prevailing conditions of inequality, poverty, and the long reach of apartheid. But at the same time, these photographers have broken with the forms that those narratives have taken.

Courtesy The Walther Collection

Santu Mofokeng, for example, in The Black Photo Album, is really the first photographer in South Africa to have turned his attention to the “found photograph” as having both aesthetic and social legitimacy. Jo Ractliffe departs radically in her early work from the tradition of landscape photography through her use of the pinhole camera. In her later books, such as As Terras do Fim do Mundo [Stevenson Gallery, 2010], she looks at landscape not as the representation of an ideal view of land, but rather as a repository of trauma and violence. In this, as well as in her rigorous attention to the facts that attach themselves to particular landscapes, Ractliffe is very similar to Goldblatt; but she departs from his influence in allowing the conceptual framework of her projects, rather than the monumental power of individual images, to dictate the shape and scope of her visual narrative.

© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

How do you see the contemporary photobook in South Africa responding to the past, but also breaking new ground in form and content?

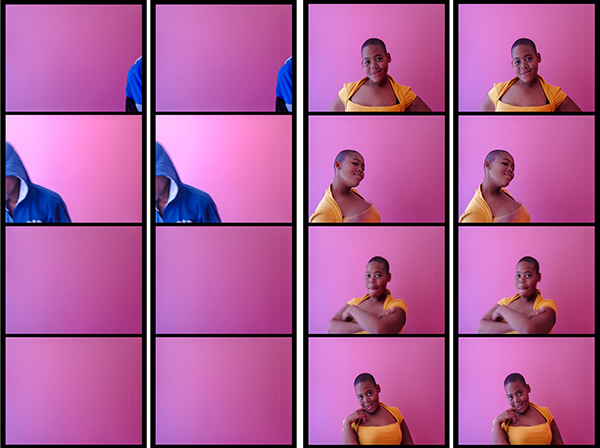

Law-Viljoen: Muholi’s extraordinary achievement, in Faces and Phases, is her ability to represent the experience of a marginalized group of people in society while at the same time suggesting the dynamic agency of the individuals in this group. This is emblematic of a profound psycho-political shift in South African art in general since the end of apartheid. The focus for many artists and photographers is less on people as representatives of a system or group than it is on the individual, as having their own, unique experience of trauma and as agent in their own life.

For black photographers in particular, there is a need to portray black people as creators and definers of their own worlds rather than as occupants of someone else’s. The political is still present and urgent in South African photography, but the formal and philosophical terms of the representation of the political have shifted quite dramatically.

Courtesy the artists and Fourthwall Books

When you opened Fourthwall Books, what types of photobooks were you most interested in publishing? What makes a book a Fourthwall book?

Law-Viljoen: We were interested in beautiful and unusual books that told unusual stories and did not rely solely on the singular image, or on a series of singular images, for their impact. Rather, we wanted to make books that were able to sustain a long engagement with their subject matter—often, though not always, by combining text and image in interesting ways.

So we looked for strong writing that had “grown” alongside the images. In other words, we were not very interested in the traditional critique produced “after the fact”—a piece of writing in which the writer looks at all the photographs she or he has been sent, then writes a “response” text. We liked projects in which images and text came into the world at about the same time. And we liked less obvious connections between images and text: short stories rather than essays, or essays apparently about something other than the stuff in the photographs. We also wanted to make “slow” books, ones in which photographers looked for a long time at the same thing from a lot of different angles.

Courtesy the artists and Fourthwall Books

How do you choose your projects? Do you work with local designers in South Africa? And where do you print your books?

Law-Viljoen: The projects that appeal to us usually are the ones that make little business sense—hence nobody else will touch them! We’ve always done our own design. Oliver Barstow was the cofounder of Fourthwall, and he designed all the books up to 2015. Since then our designer has been Carla Saunders, and we’ve sometimes had other designers work on projects—but all have been South African. We have printed books in South Africa, China, Germany, and Italy.

Courtesy the artist and Fourthwall Books

You’ve published several books about Johannesburg, including UP UP: Stories of Johannesburg’s Highrises [2016], Writing the City Into Being [2010], and Terry Kurgan’s Hotel Yeoville [2013], which seem to dissect the city, its communities, and its architecture in words and pictures. Why is Johannesburg an enduring photographic subject? What do your books—which privilege writing—offer to the ongoing portrait that artists are collectively making of Johannesburg?

Law-Viljoen: We never set out to make books about Johannesburg, but I suppose once we had made a couple, we came to be seen as the publisher of Johannesburg material. Joburg is vibrant, ugly, beautiful, violent. It has lots of hidden pockets. It’s very fragmented and divided. It’s Goldblatt’s city, it’s Mofokeng’s city, it’s Peter Magubane’s city. But it also belongs to young artists and it features in quite diff erent ways in their work. The historic and hugely important Market Photo Workshop is here—so it’s the place young photographers test their mettle. I suppose it suits us as a subject for books because it has so many stories in it, and we like stories with funny beginnings and open endings.

© and courtesy the artist and Fourthwall Books

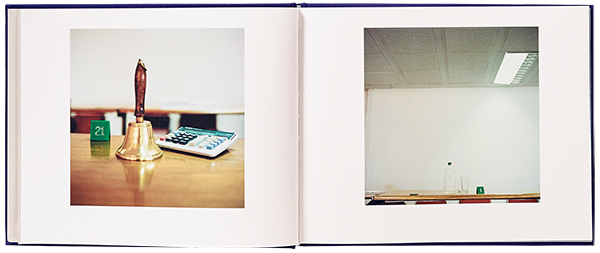

Lisa King’s captivating book Sometimes I make money one day of the week [2015] is an account of the traders working at the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange. Why were you attracted to this project?

Law-Viljoen: Lisa’s book was odd—not obvious material for a photobook, or in fact for any book. She spent a number of years taking photographs in the last manual call-out stock exchange in the world, which has now been digitized. The pictures were of a bunch of very ordinary-looking people in a very ordinary, tatty room. But it was an unexpectedly interesting story. And it came with the writer Sean Christie. He had not yet written the text when we first saw the images, but we knew his work—he’s a writer who always takes the road less traveled. And both Lisa and Sean stuck with this odd little story for a long time. They were determined to show us (and readers in general) how interesting they found it. In a way it’s the perfect Fourthwall book.

© and courtesy the artist and Fourthwall Books

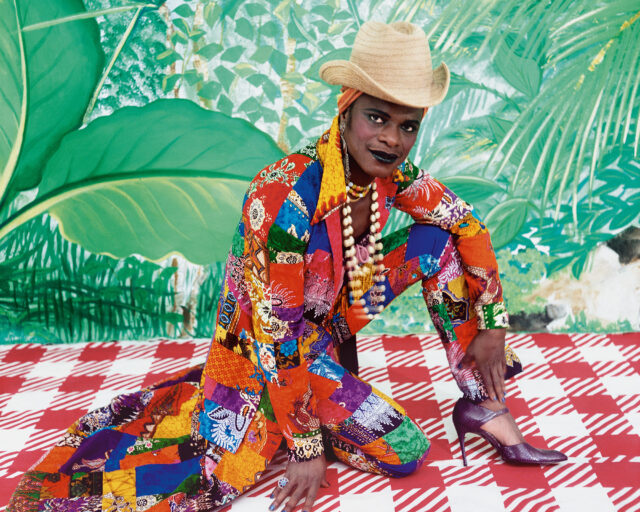

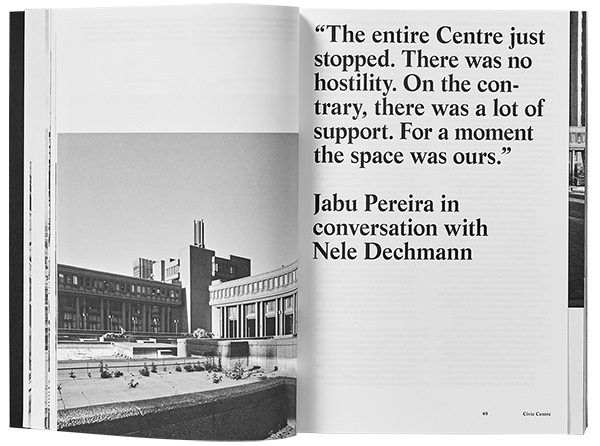

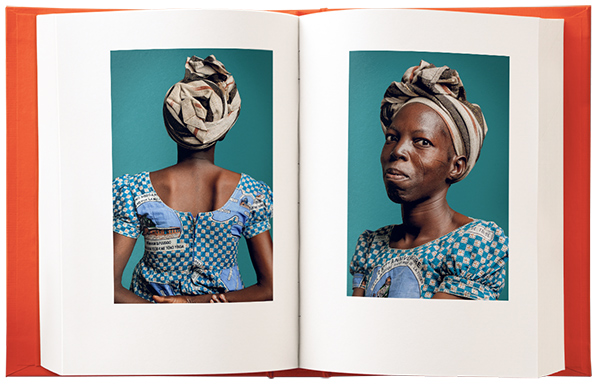

One of your most recent titles is the Ivorian photographer Joana Choumali’s Hââbré, The Last Generation [2016]. How did you learn about Choumali’s work? And could you speak about the design—the minimalist approach, the typography, and the bold choice of a bright red cover?

Law-Viljoen: Joana’s book was nominated for the 2016 Fourthwall Books Photobook Award, which is the first such award on the African continent. For Hââbré, we wanted to represent Joana’s vision of her sitters as important bearers of an old tradition—facial scarification among people from Burkina Faso who have migrated to Ivory Coast. At the same time, however, we did not want to over-romanticize them. So we decided that, by placing the interview before the image, we would make the reader “listen” to the subject in the portrait before they saw them in the image. We made the text as visual as we could: a large, bold font that prefaces each pair of images. As for the cover, the red is a foil to the cool blue background that Joana used in her portraits. It’s on the other side of the spectrum to the backdrop, but both colors have a lot of black in them.

Courtesy the artist and Fourthwall Books

What are the challenges of publishing photobooks in South Africa? What are the rewards?

Law-Viljoen: Funding is the primary challenge. The second challenge, not unrelated to the first, is the size of the book-buying market. We have to balance our desire to make beautiful books against the realities of life for most people in South Africa. We often ask ourselves about the relevance of our books, the relationship of our books to the social world we live in. We always address ourselves to these problems in the books, but the end result is out of reach for many who might otherwise like to buy them.

© and courtesy the artist

Still, by making books, you provide a measure of cultural preservation, and you also show young photographers the many ways they might communicate their ideas and vision. Do you see a growing community around photobooks in South Africa today?

Law-Viljoen: We see a greater awareness of the possibilities that a book provides for a photographer, and a growing sophistication in readers and photographers. This suggests a wider engagement with the world of books and photography outside of South Africa, which is a good thing. Perhaps we’ve also contributed to this, through the kinds of books we’ve chosen to do and the design choices we’ve made over the years.

Bronwyn Law-Viljoen is an associate professor and head of Creative Writing at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, as well as editor and cofounder of Fourthwall Books. Her debut novel is The Printmaker (Umuzi, 2016).

This article, which originally appeared in The PhotoBook Review #12, Spring 2017, is produced in collaboration with Contemporary And (C&) – Platform for International Art from African Perspectives.