On the Side of Truth

The Kenyan photojournalist Priya Ramrakha covered twentieth-century icons from Malcolm X to Miriam Makeba. Nearly fifty years after his death, a new exhibition reveals the scope of his pan-African vision.

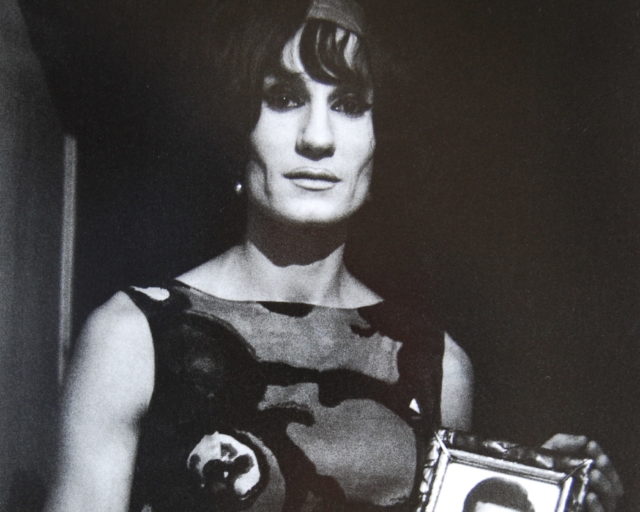

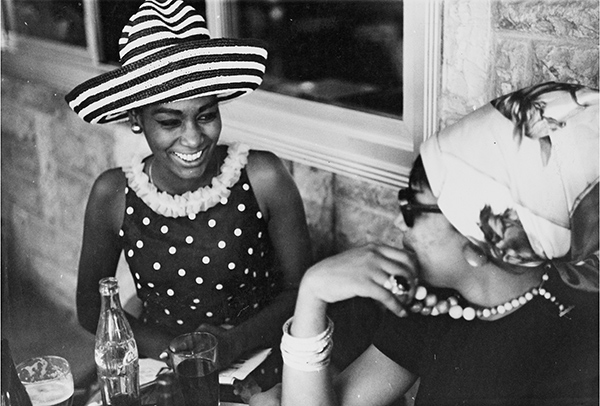

Priya Ramrakha, Models, ca. 1965

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

If he had some kind of supernatural powers, the archivist and filmmaker Shravan Vidyarthi would make sure the world, especially Africa, never forgets the name Priya Ramrakha. With the exhibition Priya Ramrakha: A Pan-African Perspective 1950–1968, cocurated by Vidyarthi and the scholar and curator Erin Haney, and recently presented at the FADA Gallery at the University of Johannesburg, the moment has arrived to illuminate Ramrakha’s story from a decades-old archive.

Ramrakha (1935–68) started working as a photographer as a teenager. He was a gifted and subtle documentarian, and yet he remains relatively unknown in his native Kenya and beyond. Born into a Kenyan Indian family, by age eighteen he was working as a photojournalist for his uncle G.L. Vidyarthi’s rebellious Nairobi newspaper, the Colonial Times. From there, Ramrakha quickly made his name. Against the grain of the British, state-owned press, Ramrakha sought to capture his subjects with an acute and penetrative, yet sympathetic, eye, and his earliest efforts focused on the anticolonial nationalist movement, the Mau Mau war, and the Kenyan populace at large.

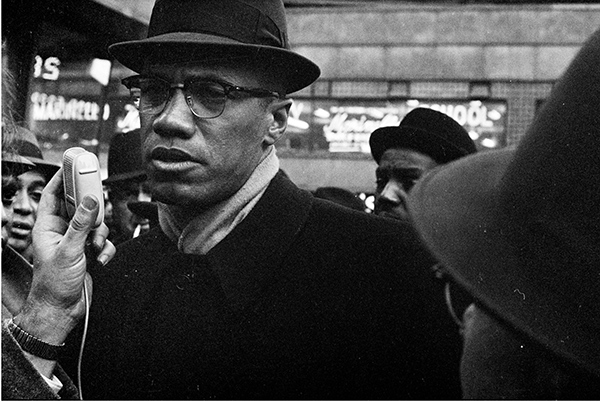

But Ramrakha was never just a one-dimensional protest photographer. His work, evident in the yellowing press cuttings of the late 1950s and early 1960s, is imbued with a jocular sense of humor, cinematic poetics, and the urgency of journalism, and paints a portrait of the artist as a young genius. At twenty-five, he crossed the Atlantic and headed to Los Angeles, where he enrolled in photography at the Art Center College. The America of the ’60s was a hotbed for all sorts of immigrant intellectuals, artists, and exiled students, mostly coming from what then was called the “third world,” and who were gripped in vicious struggles for independence. In New York, he photographed Malcolm X; in LA, Ramrakha was drawn to the civil rights movement, and met a veritable mix of activists, including Nation of Islam organizers, Martin Luther King Jr., and the South African siren Miriam “Zenzi” Makeba—of whom he made a series of intimate, frill-free, and yet alluring portraits.

Priya Ramrakha, Malcolm X and Nation of Islam protestors, New York, 1960

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Back home during the raging ’60s, as the African continent was gripped by the radicalizing fervor of rock ’n’ roll, soul music, and the quest for freedom following Ghana’s 1957 independence, Ramrakha got a freelance gig shooting for both Time and Life magazines. His work for them is unique for its unadorned yet uncomfortable portrayals of independence movements across Africa and the military takeovers that followed. Like Robert Capa, or the Polish metafictional writer Ryszard Kapuściński, Ramrakha’s immersion reveals the story of an embedded man. Although he was anticolonialist, the situations he shot and the access he gained make it difficult, at first, for the eye to discern with which side he was embedded. But, Ramrakha was embedded on the side of truth.

The exhibition in Johannesburg contained a series of battlefront portraits in Biafra, Nigeria, which tells two stories at once: the story of what’s framed in war, and what’s left out. On one hand, he tells the story of the gruesomeness of war; on the other, the story of the man who shot some of Africa’s vicious contemporary battles for self-determination. How did he get so close, so intimate, and so participative? What were the personal risks he worked in and through to beam war back to the world?

These are questions every artist—not that he referred to himself as such—has to contend with, then and now; they go to the very heart of his biography. In 1968, Ramrakha was shot dead in Owerri, Nigeria, caught in the crossfire between federal Nigeria’s army and the secessionists in Igboland’s Biafra. A CBS film crew captured his final moments; the correspondent Morley Safer tried to carry him to safety, but Ramrakha died before they reached an aid station. He was thirty-three years old.

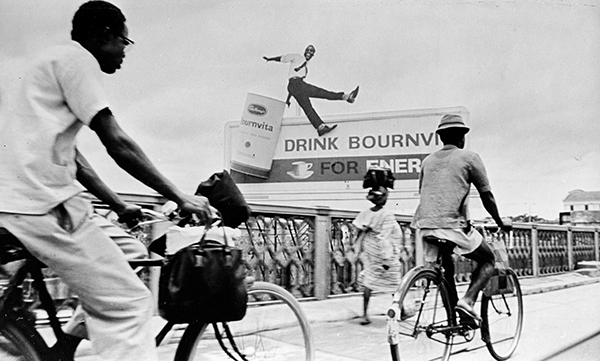

Priya Ramrakha, Bicyclists, Nairobi, Kenya, ca. 1950

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Although Ramrakha was definitely attracted to war, he also retained a lyrical aesthetic and warmth for ordinary people and their sense of dress, laughter, and the poetic lack of drama that shapes humanity’s daily mundanities. It is a poignancy drawn out of his love for people, especially fellow Africans. To Vidyarthi, a Georgetown University-trained filmmaker, Ramrakha’s life is both a pan-African archival story as much as a personal one: Vidyarthi is related to Ramrakha through his father, who was the photographer’s first cousin. Since 2004, Vidyarthi has been working on Ramrakha’s archive, searching for material for a documentary film, African Lens: The Story of Priya Ramrakha (2007).

I recently spoke with Vidyarthi and Haney about Ramrakha’s legacy and his first-ever exhibition, which could not have come at a more apt and urgent moment: South Africa once again finds itself in the eye of the storm, as fierce, tertiary students lead “decolonialization” debates and take on identity politics body armor. Who is and is not an African? What role do you play, as an artist and seer, in relation to the tumultuous times around you?

Priya Ramrakha, Two men, Nairobi, Kenya, ca. 1958

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Bongani Madondo: Why a pan-African show now? Is this a climb on the vogue-ish public discourse on decolonization revived by the student and youth movements in the U.S. and South Africa in the last three years?

Shravan Vidyarthi: This project has been a long-term labor of love, dating back to 2004, when, in Nairobi, I first began the work of recovering the neglected archive of Priya Ramrakha, who was my father’s cousin. My initial research led to the production of African Lens: The Story of Priya Ramrakha, a documentary film I directed and produced, in which I sought to bring attention to Priya’s remarkable story and photographic output. Ramrakha was a total outlier for his time. In the 1950s, he left Kenya to briefly study in the U.S., and then, in the 1950s and ’60s, he photographed all around the African continent, the U.S., and Europe for Time and Life. Priya was largely drawn to communities during the rise of anticolonial resistance and nationalism, and he focused often on ordinary people doing quietly heroic things, sometimes at great costs to life and family, as well as to the lesser known leaders and visionaries. He was not beholden to political marquee names, although he documented the major players, such as Malcolm X, with grace.

As to the question of current debates in South Africa and the U.S., there has been a surprising dovetailing, but we have been working on this project far longer. Erin’s research in West Africa and my own in Kenya brought together joint efforts like our forthcoming book on Ramrakha, as well as educational programs we are working on.

Priya Ramrakha, March, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 1964

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Erin Haney: In 2015, VIAD (Visual Identities in Art and Design) at University of Johannesburg asked us to create an inaugural exhibition of Ramrakha’s work, with a view to featuring more stories from the continent. So there are many points of urgency that we recognize, and it is not about coopting present struggles and activism around decolonization (be it in South Africa or elsewhere), or jumping on trendy bandwagons; rather, it is about being attentive to histories often neglected or sidelined in the mainstream.

We have been focused, here, on opening up a broader critical dialogue, by way of engaging Ramrakha’s visual archive. For us, the objective as curators was to situate current struggles and challenges within an extended, layered, and essentially pan-African story of colonial disentanglement.

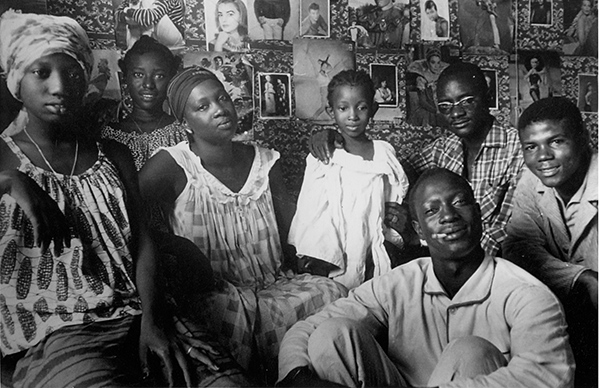

Priya Ramrakha, Family gathering, Accra, Ghana, ca. 1966

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: Should our references of pan-Africanism always be a rear-window view, always looking and celebrating the past with scant attention to a changing Africa globally? Have you factored in the current winds of “wokey” Pan-Africanism coursing through South Africa today?

Haney: Pan-Africanism in Kenya and in other places was inherently futurist and collaborative, even with its ambiguities and omissions. Pan-Africanism has never been cut off from the rest of the world, in time or space. From each of our own experiences, we see how there is still a critical absence of visual material around these stories, and much intellectual and creative work needs to go in to a necessary and critical rethinking of the period, and its politics. Our view is that history is a work of the here and now and not a fossilized past.

Seeing the responses of people in Johannesburg—the younger “born-frees” and the older generations—it was clear that the exhibition brought out distinct stories, especially in light of the public debates around decolonizing education and the sidelining of African histories that is commonplace. It’s part of a messy and ongoing dialogue—hopefully that connects with the deeper frustrations and misrepresented histories that are so profoundly troubled and debated in South Africa, and which have powerful resonances in the U.S. as well.

Vidyarthi: That said, present day Kenya does a terrible job of celebrating its pan-African heroes and helping young people connect with them, and their aspirations and ideals. Ramrakha’s work reveals important political collaborations across racial lines, especially in the pre-independence era. All of this is almost impossible to remember today. Very few people in Kenya, whether of African or Indian descent, know of the relationships forged between African and Indian freedom fighters, or the extent of those collaborations and solidarities. Symbolically, his work is rendered all the more relevant, especially in a place like Kenya where Kenyan Indians have been vilified as “non-indigenous” bourgeoisie.

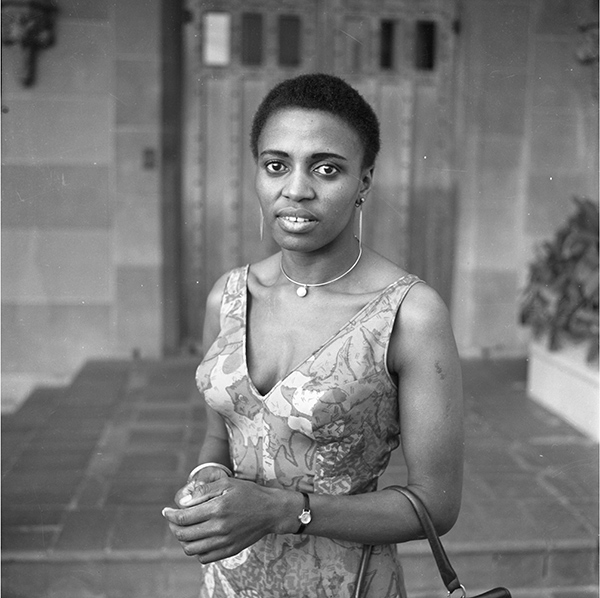

Priya Ramrakha, Miriam Makeba, New York, 1962

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: I’m particularly interested in the discovery of the photographs of the singer Miriam Makeba within the Ramrakha archive. So much love in there.

Vidyarthi: To be clear, the Makeba images have been part of Priya’s broader archive all along. They are one of many tremendously exciting subjects, most of which were never published. The inclusion of the Makeba images is, of course, an important point of connection for a South African exhibition, and one that demonstrates the kind of pan-African and international conversation that has linked independence movements across the continent, as well as associated civil rights and antiracist movements in the U.S. and elsewhere.

Priya Ramrakha, Ladies, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1964

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: Did Priya have a close relationship with Makeba at all? Looking at some of those images, the viewer is confronted with intimacy, and a sense of warmth in the subject and her surroundings.

Vidyarthi: No, but by all accounts, he was incredibly good at gaining the trust of his subjects. He would have been a student in Los Angeles during this time, and would probably have been excited to meet Makeba, given his connection to the anticolonial press in Kenya, and his interest in (and coverage of) the civil rights movement in the U.S.

Madondo: What did he think of Makeba? Are there any letters or diaries he kept that might shed a light?

Vidyarthi: Priya’s scrapbooks are essentially a visual record. Unfortunately, we don’t have any letters or diary entries around his interaction with Makeba. Some of these encounters demand a measure of imagination, which is so often an aspect of revisionary historical work!

Priya Ramrakha, Deliveries, Manhattan, 1962

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: Is this a posthumous retrospective or a fraction of Priya’s work?

Vidyarthi: It is retrospective in the sense that we are looking back at a particular continuous time and view of this person’s work, but not at all an exhaustive reflection of his career. As we are working on the book we are still digging through the archive, discovering fascinating images, and piecing together their stories.

Priya was killed in the Nigerian Civil War in 1968. Prior to that, he shot thousands of photographs. Thus, the exhibition is a selection that presents a broad overview of his practice, and will give audiences an opportunity to rethink and revisit a set of experiences and political moments that continue to resonate today, as the legacies of colonialism are grappled with and negotiated.

Priya Ramrakha, Rally for John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign, Los Angeles, 1960

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: Who, specifically, discovered these photographs?

Vidyarthi: Priya’s images were scattered across the globe. Priya’s friends had some in the U.S. and the U.K. Some were in the Time and Life archives. The most elusive, thousands of negatives and prints, were concealed in the depths of Priya’s cousin’s garage in Nairobi. Over the ten years working to gather and collate the archive, I have interviewed numerous people connected with Priya and his time. All of the photographs are presented for the first time in over fifty years.

Priya Ramrakha, Football watchers, Los Angeles, 1961

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: What state were they in?

Vidyarthi: Fortunately, many of the negatives, contact sheets, and clippings were in great condition because of Nairobi’s dry climate.

Madondo: What exactly was discovered: prints or negatives?

Vidyarthi: Both, and some letters, documents like passports, death certificates, Time and Life correspondence.

Priya Ramrakha, Salvador Dali, New York, 1962

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: How do we know the images have never been published before?

Vidyarthi: Some images in his archive have been published in Time and Life. Others were published in Drum magazine’s East Africa edition, and in Kenyan newspapers. The majority have not appeared in any publications that Ramrakha worked for, to the best of our knowledge.

Madondo: Is there a possibility that Priya shot these while on commission (say for Life) and that the photographs were not used during his time there?

Vidyarthi: We don’t know for sure, yet. It would appear that Ramrakha shot these either in New York, or at the University of California, Los Angeles, where Makeba might have been performing and visiting a cohort of continental African students there in 1961 or 1962. Ramrakha was in both places, and he attended the Art Center College in LA at that time.

Priya Ramrakha, Kenyan subjects rallying for land rights and political equality, Nairobi, Kenya, ca. 1950

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: As a photographer in those tumultuous times, roughly from 1960 to late 1968, was Priya associated with any cultural or liberation movement?

Vidyarthi: Not that I am aware of. I would say that Priya’s political drive is reflected in his photographic practice, in the kinds of stories he told, many of which are located around experiences of race, civil rights, anticolonial struggles, and experiences of independence. As one of the first African photographers for Time and Life, he was in a unique position to counter, to some degree, reductive views on African political struggles and experiences. Significant in this regard is, I believe, the attention he gave not only to key political figures and “big moments,” but also to the everyday experiences of African people.

Priya Ramrakha, Local and international press corps, Independence day, Nairobi, Kenya, December 12, 1963

© The Priya Ramrakha Foundation

Madondo: What’s next for this exhibition?

Vidyarthi: I’m thrilled that a selection of works from the recovered archive were finally on public display, and I am honored that an African audience has been able to experience images that have lain dormant for over half a century. VIAD, who commissioned and made a deep investment in this project, and the FADA Gallery were extraordinary in their commitment to see this work come to public light. We are all looking forward to seeing the work travel within South Africa, and hopefully soon to Kenya, as well as in Europe and the U.S.

Priya Ramrakha: A Pan-African Perspective, 1950–1968 was on view at the FADA Gallery, Univeristy of Johannesburg, from October 5 to November 1, 2017.